Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Now It's Official: C Olne Valley to Take Part in Llangollen Celebrations!

Now it’s Official: Colne Valley to take part in Llangollen Celebrations! Colne Valley Male Voice Choir is to take part in this year’s Llangollen International Music Festival. 2017 will see the 70th Festival and - in advance of the competition – a spectacular Gala Concert is to be held. Back last October, the organisers contacted the Choir and asked us to be part of it – but we’ve been unable to reveal the news until now. Colne Valley was the first male voice choir to take the stage, way back in the ‘Peace Festival in 1947’ and since that time the Choir has performed many times, winning the competition more times than any other male voice choir. We’ve kept up our links with Llangollen – but, nonetheless, it came as something of a surprise to Choir officials when we were approached. The organisers wanted to gather three great male voice choirs with long associations with the Festival to Llangollen’s famous tent to launch the 2017 70th Anniversary. This grand opening concert will feature ‘Canoldir’ ‘Froncysyllte’ and ‘Rhos’ male voice choirs alongside ourselves under the baton of the great conductor, Owain Arwel Hughes. We’ll all be performing with Wales’ premier ‘Cory’ Brass Band and other special guests on Monday July 3rd Choir Chairman, Peter Denby, said, “I am delighted that Colne Valley has been invited to participate in this major show-piece engagement and with the enthusiasm the Choir has shown for the idea. We look forward to being part of a spectacular milestone celebration.” Funiculi Funicula Those, like the Editor, who can vaguely recall Latin lessons (or English lessons come to that) may see this song title and ponder about ropes, cables and hillside railways - and quite right, too! funicular ADJECTIVE 1 (of a railway, especially one on a mountainside) operating by cable with ascending and descending cars counterbalanced. -

We Are Proud to Offer to You the Largest Catalog of Vocal Music in The

Dear Reader: We are proud to offer to you the largest catalog of vocal music in the world. It includes several thousand publications: classical,musical theatre, popular music, jazz,instructional publications, books,videos and DVDs. We feel sure that anyone who sings,no matter what the style of music, will find plenty of interesting and intriguing choices. Hal Leonard is distributor of several important publishers. The following have publications in the vocal catalog: Applause Books Associated Music Publishers Berklee Press Publications Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company Cherry Lane Music Company Creative Concepts DSCH Editions Durand E.B. Marks Music Editions Max Eschig Ricordi Editions Salabert G. Schirmer Sikorski Please take note on the contents page of some special features of the catalog: • Recent Vocal Publications – complete list of all titles released in 2001 and 2002, conveniently categorized for easy access • Index of Publications with Companion CDs – our ever expanding list of titles with recorded accompaniments • Copyright Guidelines for Music Teachers – get the facts about the laws in place that impact your life as a teacher and musician. We encourage you to visit our website: www.halleonard.com. From the main page,you can navigate to several other areas,including the Vocal page, which has updates about vocal publications. Searches for publications by title or composer are possible at the website. Complete table of contents can be found for many publications on the website. You may order any of the publications in this catalog from any music retailer. Our aim is always to serve the singers and teachers of the world in the very best way possible. -

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Orchestral Works Including SHEHERAZADE

Kees Bakels RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Orchestral works including SHEHERAZADE BIS-CD-1667/68 MALAYSIAN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA / KEES BAKELS BIS-CD-1667/68 RK:booklet 15/6/07 11:48 Page 2 RIMSKY-KORSAKOV, Nikolai (1844–1908) Disc 1 [74'34] Sheherazade 43'28 Symphonic Suite after the ‘Thousand and One Nights’, Op. 35 (1888) 1 I. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship 9'02 2 II. The Tale of the Kalender Prince 12'00 3 III. The Young Prince and the Young Princess 10'22 4 IV. Festival in Baghdad – The Sea – The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock Surmounted by a Bronze Warrior – Conclusion 11'50 Markus Gundermann violin solo Symphony No. 2 (Symphonic Suite), ‘Antar’ 30'01 Op. 9 (1868/75/97) 5 I. Largo – Allegro – Allegretto – Largo 11'29 6 II. Allegro 4'38 7 III. Allegro risoluto 5'22 8 IV. Allegretto – Adagio 8'09 2 BIS-CD-1667/68 RK:booklet 15/6/07 11:48 Page 3 Disc 2 [76'42] Capriccio espagnol, Op. 34 (1887) 15'00 1 I. Alborada. Vivo e strepitoso 1'12 2 II. Variazioni. Andante con moto 4'38 3 III. Alborada. Vivo e strepitoso 1'14 4 IV. Scena e canto gitano. Allegretto 4'39 5 V. Fandango asturiano – Coda. Vivace assai – Presto 3'15 6 Piano Concerto in C sharp minor, Op.30 (1882–83) 14'06 Noriko Ogawa piano The Tale of Tsar Saltan, Suite, Op. 57 (1899–1900) 19'49 7 I. The Tsar’s Farewell and Departure. Allegro – Allegretto alla Marcia 4'44 8 II. -

PYO: 11.22.15 Kimmel Center Concert

Philadelphia Youth Orchestra Louis Scaglione • Music Director Presents PHILADELPHIA YOUTH ORCHESTRA KIMMEL CENTER CONCERT SERIES Louis Scaglione • Conductor Jennifer Montone • Horn Sunday • November 22 • 2015 • 3:00 p.m. Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts Verizon Hall Welcome to the 76th Anniversary season of the Philadelphia Youth Orchestra! This year promises to “spirit you away” with the great talent and artistry of our young musicians. You have seen us here with your belief in the power and great merit of music. Our solid, sustained history affords us the ability to reach out into our diverse communities ensuring that the universal gift and language of music is known to all who desire it. The Philadelphia Youth Orchestra organization takes pride in playing a pivotal role to prepare its students for successful university and conservatory experiences. PYO prepares its students to be successful, contributing members of society, and trains them to be tomorrow’s leaders. As you settle into your seats in the acoustically and aesthetically magnificent Verizon Hall, we hope that you will delight in today’s performance. May your experience with us, today, be a catalyst for your returning to us throughout our concert season for you and your family’s music and cultural enjoyment. We welcome and appreciate your generosity and support of our mission, and look forward to welcoming you to our concerts. With much gratitude, Louis Scaglione, President and Music Director 01 Philadelphia Youth Orchestra Kimmel Center Series Philadelphia Youth Orchestra Louis Scaglione • Conductor Jennifer Montone • Horn The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts • Verizon Hall Sunday, November 22, 2015 • 3:00 p.m. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

INFANTRY HALL PROVIDENCE >©§to! Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 28 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS. MANAGER ii^^i^"""" u Yes, Ifs a Steinway" ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to you, and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extr? dollars and got a Steinway." STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere 2>ympif Thirty-fifth Season,Se 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUC per; \l iCs\l\-A Violins. Witek, A. Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet, H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Stilzen, H. Fiedler, A. -

Rimsky-Korsakov Romances

booklet-paginated:cover 11/09/2017 12:02 Page 1 5060192780772 RIMSKY-KORSAKOV ROMANCES Anush Hovhannisyan Yuriy Yurchuk Sergey Rybin 28 1 booklet-paginated:cover 11/09/2017 12:02 Page 3 Produced, engineered and edited by Spencer Cozens. Recorded 19-21 December 2016 at Steinway Recording, Fulbeck, Lincolnshire, U.K. Steinway technician: Peter Roscoe. Publisher: Moscow, Musyka. Booklet notes © 2017 Sergey Rybin. English translations of sung text © 2017 Sergey Rybin. Cover: Photograph © 2013 Anatoly Sokolov. Inside from cover: Photograph of Sergey Rybin, Anush Hovhannisyan and Yuriy Yurchuk © 2017 Inna Kostukovsky. Graphic design: Colour Blind Design. Printed in the E.U. 2 27 booklet-paginated:cover 11/09/2017 12:02 Page 5 24 Prorok Op.49, No.2 The Prophet Alexander Pushkin Dukhovnoï zhazhdoïu tomim Tormented by spiritual anguish V pustyne mrachnoï ïa vlachils’a, I dragged myself through a grim desert, I shestikrylyï serafim And a six-winged seraphim Na pereputïe mne ïavils’a; Appeared to me at a crossroads; RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Perstami l’ogkimi, kak son, With his fingers, light as a dream, Moikh zenits kosnuls’a on: He touched my eyes: ROMANCES Otverzlis’ vesh’iïe zenitsy, They burst open wide, all-seeing, Kak u ispugannoï orlitsy. Like those of a startled eagle. Moikh usheï kosnuls’a on, He touched my ears I ikh napolnil shum i zvon: And they were filled with clamour and ringing: I vn’al ïa neba sodroganïe, I heard the rumbling of the heavens, I gorniï angelov pol’ot, The high flight of the angels, I gad morskikh podvodnyï khod, The crawling of the underwater reptilians I dol’ney lozy proz’abanïe. -

Maurice Ravel, After Nikolay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov: Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Antar – Incidental Music (1910/2014) 53:33 Orchestral Works • 5 1 No

RAVEL Orchestral Works • 5 Antar – Incidental music after works by Rimsky-Korsakov Shéhérazade André Dussollier, Narrator Isabelle Druet, Mezzo-soprano Orchestre National de Lyon Leonard Slatkin Maurice Ravel, after Nikolay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov: Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Antar – Incidental music (1910/2014) 53:33 Orchestral Works • 5 1 No. 1. Rimsky-Korsakov: Antar, 1st movement: Largo – Allegro giocoso – Furioso – Allegretto vivace – Adagio – Allegretto vivace – Largo Ravel was still a teenager when he fell under the spell of that the Orient had exerted over me since my childhood.” Russian music: he discovered both The Five That said, the work also boasts a number of trademark “Le désert n’est pas vide…” 11:09 (Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Cui, Borodin and Ravelian qualities – clarity of discourse, sophistication of 2 No. 1 bis. Ravel: Allegro 0:35 Balakirev) and the Javanese gamelan at the age of detail, and an ongoing conflict between instinct and 3 No. 2. Ravel: Cadenza ad libitum fourteen when he visited the 1889 Universal Exhibition in control. “En ce temps-là…” 1:39 Paris (an event whose centrepiece was the newly Ravel’s choice of orchestral forces also reflects the 4 No. 3. Ravel: Allegretto constructed Eiffel Tower). Ten years later, the dual impact influence of Debussy: divided strings, a large wind “Sa mère, Zébiba…” 0:53 of Russia and the Orient bore fruit in the “fairy overture” section, celesta, two harps and a rich array of percussion. 5 No. 5. Ravel: Allargando Shéhérazade, originally intended to be the curtain-raiser But where Debussy favours doubling and timbral “Sa renommée grandissait avec lui…” 0:32 for an opera based on the Arabian Nights – a work that in blending, uses the warmth of the brass section and the end never saw the light of day. -

Christopher Bengochea, Tenor Soloist Michael Paul Gibson, Music Director and Conductor

Christopher Bengochea, tenor soloist Michael Paul Gibson, music director and conductor Saturday Sunday 17 Nov. 2012 18 Nov. 2012 7:30 pm 4:00 pm Holy Trinity Saint Mark’s Episcopal Church, Episcopal Church, Menlo Park Palo Alto Ticket Donation $20/$15/Children 12 and under free with adult Brahms: Variations on a Theme By Haydn Op 56a (1873) "Var. I: Poco piu animato "Var. II: Piu vivace "Var. III: Con moto "Var. IV: Andante con moto "Var. V: Vivace "Var. VI: Vivace "Var. VII: Grazioso "Var. VIII: Presto non troppo "Finale: Andante Tosti: A Marechiare (1886) Verdi: La donna è mobile (1851) from Rigoletto ! Christopher Bengochea , Tenor soloist Fauré: Pavane (1887) Denza: Funiculí Funiculà (1880)" " Christopher Bengochea , Tenor Soloist " Menlo Park Chorus, April McNeely, Music Director "Audience singalong di Capua: O Sole Mio (1898) " Christopher Bengochea , Tenor Soloist ""INTERMISSION Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-17)) "1. Prélude "2. Forlane "3. Menuet "4. Rigaudon Rimsky-Korsakov : Capriccio Espagnol (1887) "1. Alborada "2. Variazioni "3. Alborado "4. Scena e canto gitano "5. Fandango asturiano ! Variations on a Theme By Haydn (1873) by Johannes Brahms "To this day, the theme on which this magnificent work was based remains something of a mystery. Brahms gave credit to the illustrious composer, Joseph Haydn, but it seems he was misled. Publishers, in those days, were wont to misattribute works to better known composers in order to boost sales and, furthermore, modern scholars do not believe the theme matches Haydn's style. Instead, it is thought Haydn#s pupil, Ignaz Pleyel may have been responsible though it is not certain. -

Memories from “CHITARRE ACUSTICHE D’ITALIA”

Art Phillips Music Design PO Box 219 Balmain NSW 2041 Tel: +61 2 9810-6611 Fax: +61 2 9810-6511 Cell: +61 (0) 407 225 811 ART PHILLIPS – memories from “CHITARRE ACUSTICHE D’ITALIA” Each of the songs included in “ Chitarre Acustiche d’Italia ” have been an important element for the music career of the two-time Emmy and APRA awarded artist composer Art Phillips (Arturo Di FIlippo). The Italian heritage of his father and grandfather and their love for music, drove Art into the music scene and inspired him to create, after more than 30 years of global success, a tribute album like this. This album is the story of Italian family memories and traditions. Below, Art Phillips explains the feelings and memories related to each track contained on the album. 1. Tra Veglia e Sonno (Between Wakefulness and Sleep) A piece I learnt from my father and grandfather in my very early years. They would play this every time they got together in my grandfathers kitchen with their guitar and mandolin, where live music would be an important part in our family life. Grandpa lived just around the corner from my home where our backyards connected, in fact he was also a carpenter and brick mason and built our home as well as all the other homes located around our block. Most of his children lived next door or just around the corner with connecting back yards. We would visit my grandpa and grandma each and every day, and there would not be many days in passing that my guitar wouldn’t join into the family’s musical moments. -

RUSSIAN & UKRAINIAN Russian & Ukrainian Symphonies and Orchestral Works

RUSSIAN & UKRAINIAN Russian & Ukrainian Symphonies and Orchestral Works Occupying a vast land mass that has long been a melting pot of home-spun traditions and external influences, Russia’s history is deeply encrypted in the orchestral music to be found in this catalogue. Journeying from the Russian Empire through the Soviet era to the contemporary scene, the music of the Russian masters covers a huge canvas of richly coloured and immediately accessible works. Influences of folklore, orthodox liturgy, political brutality and human passion are all to be found in the listings. These range from 19th-century masterpieces penned by ‘The Mighty Five’ (Balakirev, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Borodin, and Cui) to the edgy works of Prokofiev and Shostakovich that rubbed against the watchful eye of the Soviet authorities, culminating in the symphonic output of one of today’s most noted Russian composers, Alla Pavlova. Tchaikovsky wrote his orchestral works in a largely cosmopolitan style, leaving it to the band of brothers in The Mighty Five to fully shake off the Germanic influence that had long dominated their homeland’s musical scene. As part of this process, they imparted a thoroughly ethnic identity to their compositions. The titles of the works alone are enough to get the imaginative juices running, witness Borodin’s In the Steppes of Central Asia, Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh, and Mussorgsky’s St John’s Night on the Bare Mountain. Supplementing the purely symphonic works, instrumental music from operas and ballets is also to be found in, for example, Prokofiev’sThe Love for Three Oranges Suite, Shostakovich’s four Ballet Suites, and Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

Symphony Program

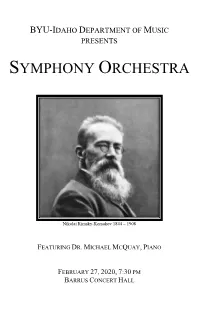

- Concert Etiquette Guidelines - BYU-IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Please be courteous and respectful to your fellow audience members PRESENTS and the performers during this concert by observing the following guidelines: I. Refrain from ALL talking or whispering during the performance of the music. S YMPHONY ORCHESTRA (Feel free to comment to your fellow audience members during applause or between pieces.) II. Turn off all electrical devices such as watches, tablets, computers, and cell phones. III. If you have to leave or re-enter the Concert Hall, please do so only between numbers. IV. Please hold all applause during the silent breaks between individual movements of large works until all the movements have been performed. (see example below) Symphony #5 in C minor ................................. Beethoven I. Allegro con brio (1st movement) II. Andante con moto (2nd movement) III. Allegro (3rd movement) IV. Allegro (4th movement) Thank you for helping create an appropriate and enjoyable atmosphere for all who have come to hear this concert. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov 1844 – 1908 Please sit bacK and enjoy! FEATURING DR. MICHAEL MCQUAY, PIANO Eliza R. Snow Society for the Performing and Visual Arts FEBRUARY 27, 2020, 7:30 PM For more information about becoming a member, contact: BARRUS CONCERT HALL www.byui.edu/snowsociety or call 208-496-1128/800-227-4257 was uncommon in western classical style and incorporated Orientalism: the use of distinctly eastern melodic and harmonic ideas to set their music apart from German composers of the time period. DAHO YMPHONY RCHESTRA BYU-I S O Rimsky-Korsakov first attempted this style in his Antar Symphony.