The Arts & Crafts Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Ruskin and South Kensington: Contrasting Approaches to Art Education

Ruskin and South Kensington: contrasting approaches to art education Anthony Burton This article deals with Ruskin’s contribution to art education and training, as it can be defined by comparison and contrast with the government-sponsored art training supplied by (to use the handy nickname) ‘South Kensington’. It is tempting to treat this matter, and thus to dramatize it, as a personality clash between Ruskin and Henry Cole – who, ten years older than Ruskin, was the man in charge of the South Kensington system. Robert Hewison has commented that their ‘individual personalities, attitudes and ambitions are so diametrically opposed as to represent the longitude and latitude of Victorian cultural values’. He characterises Cole as ‘utilitarian’ and ‘rationalist’, as against Ruskin, who was a ‘romantic anti-capitalist’ and in favour of the ‘imaginative’.1 This article will set the personality clash in the broader context of Victorian art education.2 Ruskin and Cole develop differing approaches to art education Anyone interested in achieving artistic skill in Victorian England would probably begin by taking private lessons from a practising painter. Both Cole and Ruskin did so. Cole took drawing lessons from Charles Wild and David Cox,3 and Ruskin had art tuition from Charles Runciman and Copley Fielding, ‘the most fashionable drawing master of the day’.4 A few private art schools existed, the most prestigious being that run by Henry Sass (which is commemorated in fictional form, as ‘Gandish’s’, in Thackeray’s novel, The Newcomes).5 Sass’s school aimed to equip 1 Robert Hewison, ‘Straight lines or curved? The Victorian values of John Ruskin and Henry Cole’, in Peggy Deamer, ed, Architecture and capitalism: 1845 to the present, London: Routledge, 2013, 8, 21. -

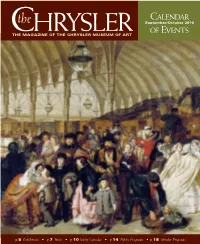

Calendar of Events

Calendar the September/October 2010 hrysler of events CTHE MAGAZINE OF THE CHRYSLER MUSEUM OF ART p 5 Exhibitions • p 7 News • p 10 Daily Calendar • p 14 Public Programs • p 18 Member Programs G ENERAL INFORMATION COVER Contact Us The Museum Shop Group and School Tours William Powell Frith Open during Museum hours (English, 1819–1909) Chrysler Museum of Art (757) 333-6269 The Railway 245 W. Olney Road (757) 333-6297 www.chrysler.org/programs.asp Station (detail), 1862 Norfolk, VA 23510 Oil on canvas Phone: (757) 664-6200 Cuisine & Company Board of Trustees Courtesy of Royal Fax: (757) 664-6201 at The Chrysler Café 2010–2011 Holloway Collection, E-mail: [email protected] Wednesdays, 11 a.m.–8 p.m. Shirley C. Baldwin University of London Website: www.chrysler.org Thursdays–Saturdays, 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Carolyn K. Barry Sundays, 12–3 p.m. Robert M. Boyd Museum Hours (757) 333-6291 Nancy W. Branch Wednesday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Macon F. Brock, Jr., Chairman Thursday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Historic Houses Robert W. Carter Sunday, 12–5 p.m. Free Admission Andrew S. Fine The Museum galleries are closed each The Moses Myers House Elizabeth Fraim Monday and Tuesday, as well as on 323 E. Freemason St. (at Bank St.), Norfolk David R. Goode, Vice Chairman major holidays. The Norfolk History Museum at the Cyrus W. Grandy V Marc Jacobson Admission Willoughby-Baylor House 601 E. Freemason Street, Norfolk Maurice A. Jones General admission to the Chrysler Museum Linda H. -

Scots and of Edinburgh-Educated Englishmen Who Were Involved in Either Governing Or Teaching at the University (H

University College London: The Scottish Connection Rosemary Ashton One of the most striking things about the founding and early years of the University of London (later University College London) is the very large number of Scots and of Edinburgh-educated Englishmen who were involved in either governing or teaching at the University (H. Hale Bellot, University College London 1828–1926, 1929). Of the original founders, the two most important, Thomas Campbell and Henry Brougham, were Scottish-born and educated. Thomas Campbell, a poet of some reputation in the early years of the nineteenth century, was born in Glasgow and attended the university there in the early 1790s. Henry Brougham, who took the title Baron Brougham and Vaux when he was appointed Lord Chancellor in the whig administration which took office in 1830 and passed the great Reform Act of 1832, was born in Edinburgh and studied there in the 1790s, becoming a lawyer and one of the founders of the Whig Edinburgh Review in 1802. Others involved in founding the new University in London in 1825 were Dr George Birkbeck, an Englishman who took his medical degree in Edinburgh in 1799, James Mill and Joseph Hume, who were at school together in Montrose and who both studied in Edinburgh in the 1790s, James Loch, an Edinburgh- educated Scottish lawyer and estate manager, Zachary Macaulay, father of Thomas Babington Macaulay and a self-educated Scot, and Leonard Horner, the first Warden of the University of London, born and educated in Edinburgh, where he was a contemporary and friend of Brougham and Mill. -

Cosmic Architecture Kozmička Arhitektura

je značio nešto poput ‘univerzuma, reda i ornamenta’. [...] Za stare Grke riječ ‘Kosmos’ stavljena je u opreku s riječi ‘Chaos’. Kaos je prethodio nastanku svijeta kakvog poznajemo, ali ga Kozmička je naslijedio Kozmos koji je simbolizirao apsolutni red svi- jeta i ukupnost njegovih prirodnih fenomena. [...] Stari grčki ‘Kosmeo’ znači ‘rasporediti, urediti i ukrasiti’, a osoba Kosmése arhitektura (ukrašava) sebe kako bi svoj Kozmos učinila vidljivim.2 kako ¶ Ornament ima gramatiku. Ornament bi trebao posje- dovati prikladnost, proporcije, sklad čiji je rezultat mir... onaj mir koji um osjeća kada su oko, intelekt i naklonosti zadovo- Cosmic ljeni.3 ¶ Vjerujem, kao što sam rekao, da se može projektirati izvrsna i lijepa zgrada koju neće krasiti nikakvi ornamenti; ali jednako čvrsto vjerujem da se ukrašenu građevinu, skladno zamišljenu, dobro promišljenu, ne može lišiti njezinog sustava architecture ornamenata, a da se ne uništi njezina individualnost.4 ¶ Tipičan postupak drevne arhitekture je dodavanje idealnih aspekata ili idealnih struktura površini zgrade. [...] Cijepanje ili klizanje stvarne površine zida u izražajnu površinu je čin transfor- macije. ¶ Govori li nepravilna evolucija kamena o nevjerojat- noj gotičkoj priči o ljudskom životu? Ili je to usputna pojava nevažnih činjenica iscrpljenih kamenoloma i klesara? Ili je to pustolovina vremena? 5 gdje ¶ Ornament je svjesna zanatska intervencija u proi- napisao fotografije Arhiva / Archive Alberto Alessi (aaa) zvodnji polugotovih proizvoda, prije nego što budu montirani written by photographs by Arhiva / Archive Alinari (aa) na gradilištu. Ornament stvara sidrenu točku protiv homo- Ruskin Library, University of Lancaster (rl) genizacije i uniformnosti suvremene građevinske produkcije. Ornamentacija omogućuje izravan odgovor na lokalne uvjete proizvodnje, na geografske ili kulturne osobitosti. -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

THE SCIENCE and ART DEPARTMENT 1853-1900 Thesis

THE SCIENCEAND ART DEPARTMENT 1853-1900 Harry Butterworth Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph. D. Department of Education University of Sheffield Submitted July 1968 VOLUMELWO Part Two - Institutions and Instruments PART TWO INSTITUTIONS AND INSTRUMENTS CHAPTER SIX The development of facilities for the teaching of Science CHAPTER SEVEN The South Kensington Science complex CHAPTER EIGHT The development of facilities for the teaching of Art CHAPTER NINE The South Kensington Art complex CHAPTER TEN The Inspectors CHAPTER ELEVEN The Teachers CHAPTER TWELVE Students, Scholarships and Text-books. CHAPTER SIX THE DEVELOPMENT OF FACILITIES FOR THE TEACHING OF SCIENCE a) Schemes before 1859 i) The basic difficulties ii) A separate organizational scheme iii) A meagre response b) Provincial institutions in the early days i) Trade Schools ii) Mining Schools iii) Navigation Schools iv) Science Schools v) The arrangements for aid c) The Science subjects : general development i) Major divisions ii) A "newt' subject: Physiography iiz. 3 yS iii) Other "new" subjects: Agriculture and Hygiene iv) Relative importance of the "divisional' d) The machinery of payments on results in Science i) The general principles ii) Specific applications iii) The Departmental defence e) The organisation of the system of examining f) Abuses of the examinations system i) The question of "cram"" ii) The question of "security" g) The Science Subjects : "Pure" or "Applied"" ? i) Basic premises ii) Reasons for reluctance to aid "trade teaching" iii) criticisms of the "pure" -

Victoria Albert &Art & Love ‘Incessant Personal Exertions and Comprehensive Artistic Knowledge’: Prince Albert’S Interest in Early Italian Art

Victoria Albert &Art & Love ‘Incessant personal exertions and comprehensive artistic knowledge’: Prince Albert’s interest in early Italian art Susanna Avery-Quash Essays from two Study Days held at the National Gallery, London, on 5 and 6 June 2010. Edited by Susanna Avery-Quash Design by Tom Keates at Mick Keates Design Published by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2012. Royal Collection Enterprises Limited St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1JR www.royalcollection.org ISBN 978 1905686 75 9 First published online 23/04/2012 This publication may be downloaded and printed either in its entirety or as individual chapters. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for non-commercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses please contact Royal Collection Enterprises Limited. www.royalcollection.org.uk Victoria Albert &Art & Love ‘Incessant personal exertions and comprehensive artistic knowledge’: Prince Albert’s interest in early Italian art Susanna Avery-Quash When an honoured guest visited Osborne House on the Isle of Wight he may have found himself invited by Prince Albert (fig. 1) into his private Dressing and Writing Room. This was Albert’s inner sanctum, a small room barely 17ft square, tucked away on the first floor of the north-west corner of the original square wing known as the Pavilion. Had the visitor seen this room after the Prince’s rearrangement of it in 1847, what a strange but marvellous sight would have greeted his eyes! Quite out of keeping with the taste of every previous English monarch, Albert had adorned this room with some two dozen small, refined early Italian paintings,1 whose bright colours, gilding and stucco ornamentation would have glinted splendidly in the sharp light coming from the Solent and contrasted elegantly with the mahogany furniture. -

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) Had Only Seven Members but Influenced Many Other Artists

1 • Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 2 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900 February 17, 2013 - May 19, 2013

Updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 | 2:36:43 PM Last updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 Updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 | 2:36:43 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900 February 17, 2013 - May 19, 2013 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required (*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Ford Madox Brown The Seeds and Fruits of English Poetry, 1845-1853 oil on canvas 36 x 46 cm (14 3/16 x 18 1/8 in.) framed: 50 x 62.5 x 6.5 cm (19 11/16 x 24 5/8 x 2 9/16 in.) The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Presented by Mrs. W.F.R. Weldon, 1920 William Holman Hunt The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, 1854-1860 oil on canvas 85.7 x 141 cm (33 3/4 x 55 1/2 in.) framed: 148 x 208 x 12 cm (58 1/4 x 81 7/8 x 4 3/4 in.) Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Presented by Sir John T. -

Theorizing Ornament Estelle Thibault

From Herbal to Grammar : Theorizing Ornament Estelle Thibault To cite this version: Estelle Thibault. From Herbal to Grammar : Theorizing Ornament. Fourth International Conference of the European Architectural History Network, Jun 2016, Dublin, Ireland. pp.384-394. hal-01635839 HAL Id: hal-01635839 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01635839 Submitted on 27 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EAHN Dublin 2016 1 PROCEEDINGS OF THE FOURTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE EUROPEAN ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY NETWORK Edited by Kathleen James-Chakraborty EAHN Dublin 2016 2 Published by UCD School of Art History and Cultural Policy University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin, Ireland. Copyright © UCD School of Art History and Cultural Policy No images in this publication may be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. ISBN 978-1-5262-0376-2 EAHN Dublin 2016 3 * Indicates full paper included Table of Contents KEYNOTE .................................................................................................................................... -

Traces Volume 4, Number 4 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Traces, the Southern Central Kentucky, Barren Kentucky Library - Serials County Genealogical Newsletter 1-1977 Traces Volume 4, Number 4 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/traces_bcgsn Part of the Genealogy Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Traces Volume 4, Number 4" (1977). Traces, the Southern Central Kentucky, Barren County Genealogical Newsletter. Paper 63. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/traces_bcgsn/63 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Traces, the Southern Central Kentucky, Barren County Genealogical Newsletter by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUTH CENTRAL KENTUCKY HISTORICAL QUARTERLY VOL 4 GLASGOW. KENTUCKY^ JANUARY 3977 NO 4 CONTENTS PAGE DIARY OF LITTLEBERRY J HALEY, DD 80 OFFICERS AND MEN IN LORD DUNMORE'S WAR 84 CLINTON COUNTY KENTUCKY VITAL STATISTICS 1856-57-53 - 87 SMITHS GROVE, KENTUCKY CEMETERY RECORDS - 92 1976 MEMBERSHIP 96 NEWS - NOTES - NOTICES 100 LOCKE FAMILY ASSOCIATION 100 HAPPY 105TH BIRTHDAY LUCY A WARD lOl QUERIES 102 BOOKS ^ BOaCS - BOOKS - , . 1.05 Membership Dues $5.00 Per Calendar Year Includes Issues Published January - April - July - October. Members Joining Anytime During The Year Receive The Four Current Year Issues Only. Queries Are Free to Members. Dues Are Payable January. Back Issues As Long As Available Are $1.50 Each. SEND CHECK TO ADDRESS BELOW South Central Kentucky Historical and Genealogical Society, Inc.