Human Self As Information Agent: Functioning in a Social Environment Based on Shared Meanings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Link to Dissertation

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Ripening or rotting? Examining the temporal dynamics of team discussion and decision making in long-term teams. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Media, Technology, and Society By Ilya Gokhman EVANSTON, ILLINOIS September 2020 2 ABSTRACT More than a quarter century of research finds that teams often fail to make high-quality decisions. This literature is based on observing team decisions in one-off decision making episodes, when in reality, most teams work together for an extended period of time, making repeated decisions together. Do teams improve or decline on decision making effectiveness over time? To answer this question, this dissertation contributes three studies on team decision making, examining how the processes and outcomes of team decision making evolve over time. In order to study team decision making over time, one needs parallel and comparable tasks on which to observe process and performance. And so, Study 1 developed and validated five parallel hidden profile tasks that require teams to share unique information in order to identify the optimal solution from three options. Using this newly developed battery of tasks, Studies 2 and 3 used mixed-methods to understand team decision making over time in eight 4-person teams. Study 2 was quantitative, examining the discussion and decision quality of teams during multiple sequential decision making episodes. Study 3 was qualitative, exploring the conversational dynamics over time. Quantitative analysis found that teams show an initial increase and subsequent decrease in discussion and decision quality as they work together. -

The Effects of Mentioning Information, Shared Information Bias, Ownership Bias, Reiteration, and Confirmation Bias Lyn M

Perceived Importance of Information: The Effects of Mentioning Information, Shared Information Bias, Ownership Bias, Reiteration, and Confirmation Bias Lyn M. van Swol To cite this version: Lyn M. van Swol. Perceived Importance of Information: The Effects of Mentioning Information, Shared Information Bias, Ownership Bias, Reiteration, and Confirmation Bias. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, SAGE Publications, 2007, 10 (2), pp.239-256. 10.1177/1368430207074730. hal-00571647 HAL Id: hal-00571647 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00571647 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2007 Vol 10(2) 239–256 Perceived Importance of Information: The Effects of Mentioning Information, Shared Information Bias, Ownership Bias, Reiteration, and Confi rmation Bias Lyn M. Van Swol Northwestern University Participants were given information for and against the decriminalization of marijuana and discussed the issue in groups. Factors affecting rated importance of information after the group discussion were examined. Participants did not rate information that was mentioned during the discussion as more important than information not mentioned, and participants did not rate shared information they mentioned as more important than unshared information. -

A Review of the Effects of Group Interaction on Processes and Outcomes in Analytic Teams

WORKING P A P E R The Group Matters A Review of the Effects of Group Interaction on Processes and Outcomes in Analytic Teams SUSAN G. STRAUS, ANDREW M. PARKER, JAMES B. BRUCE, AND JACOB W. DEMBOSKY WR-580-USG April 2009 This product is part of the RAND working paper series. RAND working papers are intended to share researchers’ latest findings and to solicit informal peer review. They have been approved for circulation by RAND National Security Research Division but have not been formally edited or peer reviewed. Unless otherwise indicated, working papers can be quoted and cited without permission of the author, provided the source is clearly referred to as a working paper. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. is a registered trademark. - iii – PREFACE This Working Paper explores the implications of using groups to perform intelligence analysis. This report reviews theory and research on the effects of group interaction processes on judgment and decision making in analytical teams. It describes the benefits and drawbacks of using groups for analytical work, common processes that prevent groups from reaching optimal levels of performance, and strategies to improve processes and outcomes in intelligence analysis teams. This work is based on a review of the literature in social and experimental psychology, organizational behavior, behavioral decision science, and other social science disciplines, as well as the limited amount of group research in the intelligence literature. Included in this review is a bibliography consisting of key references organized by topic, with annotations for selected articles based on relevance to group processes in intelligence analysis. -

The Psychology of Groups | Noba

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book Jepson School of Leadership Studies chapters and other publications 2014 The syP chology of Groups Donelson R. Forsyth University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/jepson-faculty-publications Recommended Citation Forsyth, Donelson R. "The sP ychology of Groups." In Psychology, edited by R. Biswas-Diener and E. Diener. Noba Textbook Series. Champaign, IL: DEF Publishers, 2014. http://nobaproject.com/textbooks/introduction-to-psychology-the-full-noba-collection. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Jepson School of Leadership Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book chapters and other publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Psychology of Groups | Noba University of Richmond This module assumes that a thorough understanding of people requires a thorough understanding of groups. Each of us is an autonomous individual seeking our own objectives, yet we are also members of groups— groups that constrain us, guide us, and sustain us. Just as each of us influences the group and the people in the group, so, too, do groups change each one of us. Joining groups satisfies our need to belong, gain information and understanding through social comparison, define our sense of self and social identity, and achieve goals that might elude us if we worked alone. -

Pivot Thinking

PIVOT THINKING AND THE DIFFERENTIAL SHARING OF INFORMATION WITHIN NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT TEAMS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Mark Schar August 2011 © 2011 by Mark F Schar. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/dz361xm2614 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Larry Leifer, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Pamela Hinds I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard Shavelson Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii ABSTRACT Functionally diverse team members bring unique sets of cognitive styles to team interaction; it is less clear how these differences affect the exchange of critical, mutually required team information. -

Unpacking the Board a Comparative and Empirical Perspective on Groups in Corporate Decision-Making

HAMANN_FINAL.DOCX 8/30/14 4:09 PM Unpacking the Board A Comparative and Empirical Perspective on Groups in Corporate Decision-Making Hanjo Hamann† Collegial decision-making is relevant for a host of legal questions and in particular for corporate law. What do we know about its empirical effects? Less than we could. As of yet, pertinent review articles usually (1) assume rather than analyze how much the law actually mandates collegial decision- making, (2) rely mostly on “classical” studies of decision-making or those from behavioral economics, while underrating a century’s worth of previous empirical research, and (3) review the evidence anecdotally with little regard for the robustness of each study’s findings. As a consequence, scholars from corporate law and economics even today rely on theories and evidence which were disproved years ago. The present paper is a remedy. It combines a thorough comparative analysis of corporate statutes with a comprehensive research of empirical evidence, resulting in an assessment of the robust empirical effects of collegial decision-making. Finding that groups tend to deteriorate decision quality and exacerbate cognitive biases, this paper calls upon corporate law to design institutional remedies. Knowing more about these empirical effects will help scholars to identify and eliminate faulty arguments, and thereby improve governance policy and the legal discourse as a whole. † Visiting Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn (Germany). This paper is based on the author’s German Ph.D. thesis titled “Evidenzbasierte Jurisprudenz. Methoden empirischer Forschung und ihr Erkenntniswert für das Recht am Beispiel des Gesellschaftsrechts” (Evidence Based Jurisprudence. -

Special Topics in I/O Psychology

Zárate, social psych 1 Psychology 6330 - Social Psychology, Spring, 2016 Dr. Michael A. Zárate When: Monday, 3 to 5:50 Where: Quinn 103 Contact info: Email: [email protected] Office: Psych 309c, Phone 747 6569 Email is my preferred method of communication. Office hrs. Monday, 10 to 12 and by appointment. Changes will be made as necessary. Course objectives: The primary goal of the course is to introduce you to some basic social psychological models of person and group perception and social behavior. The emphases are on basic areas of social psychology, recent developments, and a few applied areas. Discussion will focus on integrating multiple perspectives and developing new lines of research. A secondary goal will be to consider collaborative projects from a multi-theoretical perspective. How can your theoretical perspective shed light on the research projects going on in other labs? Do your experimental methods lend themselves easily to studying other issues? The course is a seminar type course. It will require reading multiple journal articles per week and discussion. Written assignments will include weekly 1 page summaries of the readings, and one 12 page research proposal. The proposal will be on a topic of interest to the student and integrate social psychological constructs with your on-going research projects. Grades: Grades will be based on three things. Twenty percent of your grade will be from class participation. Did you do the readings and can you contribute? This will be determined partially by your performance on pop quizzes and my own impression of your in class comments. Forty percent of your grade will be from the assigned one page reviews. -

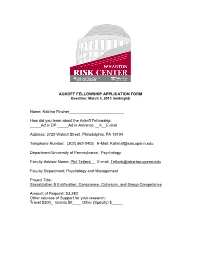

ACKOFF FELLOWSHIP APPLICATION FORM Name

ACKOFF FELLOWSHIP APPLICATION FORM Deadline: March 3, 2013 (midnight) Name: Katrina Fincher_________________________ How did you learn about the Ackoff Fellowship: _____Ad in DP _____Ad in Almanac __X__E‐mail Address: 3720 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 Telephone Number: (302) 562-0403 E‐Mail: [email protected] Department/University of Pennsylvania: Psychology Faculty Advisor Name: Phil Tetlock__ E‐mail: [email protected] Faculty Department: Psychology and Management Project Title: Sacralization & Entification: Conscience, Cohesion, and Group Competence Amount of Request: $3,380 Other sources of Support for your research: Travel $300_ Grants $0____ Other (Specify) $_____ 1 Sacralization & Entification: Conscience, Cohesion, and Group Competence Russell Ackoff Doctoral Fellowship, 2013 Application Katrina Fincher and S. Emlen Metz Doctoral Students Psychology Department Mailing Address: 3720 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 Email: [email protected] 2 Moral values enable us to live together in society. Shared value systems can facilitate social interactions in several ways. Evolutionary psychologists have long arGued that moral norms like loyalty, fairness, and honesty are necessary for cooperative social processes like reciprocal altruism to work (Wilson, 1979). However, moral values can also result from the sacralization (makinG sacred) of social norms that are not directly linked to cooperation. It has repeatedly been theorized that a primary function of sacralization is to sustain and protect the solidarity of the society in which they are held (J. Baron & Spranca, 1997; Durkheim, 1933; Merton, 1949/1968; Tetlock, Kristel, Elson, Green, & Lerner, 2000). In the proposed set of studies, we explore the effect of sacralization on in-group entification. Specifically, we suGGest moral values lead to a more positive coGnitive representation of the group, increased prosocial behavior, and greater cooperation. -

The Tragedy of Democratic Decision Making

The Tragedy of Democratic Decision Making Klaus Fiedler, Joscha Hofferbert, Franz Woellert, Tobias Krüger (Universität Heidelberg) and Alex Koch (University of Cologne) To appear in: Joseph P. Forgas, William Crano & Klaus Fiedler (Eds.), Social Psychological Approaches to Political Psychology Word count: xxxx Running head: Tragedy of democracy Author note: The research underlying the present chapter was supported by a Koselleck-grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Fi 294 / 22-2). Helpful comments were provided by Michaela Wänke on a draft of this chapter are gratefully acknowledged. 2 Tragedy of democracy Abstract Analogous to Hardin’s tragedy of the commons – the inability to exploit the advantage of cooperation in dilemma situations – the present chapter is devoted to another major political deficit: the inability to exploit the group advantage in democratic decision making. Democracies delegate virtually all legislative, executive, and juridical decisions to groups. However, groups often fail to take advantage of the “wisdom of crowd”, because leadership styles and procedural styles undermine the stochastic independence of individual opinions. The failure of groups to mobilize their potential is particularly evident in so-called hidden- profile tasks that call for effective communication of distributed information resulting from a division of labor. While previous research suggests that groups manage to find out the best decision option if only the hidden profiles are made transparent, the research reported in the present paper suggests that the failure to consider dissenters and minority arguments will persist. This relentless tragedy of democratic decision making reflects the meta-cognitive inability to suppress the impact of selective repetition on judgment formation. -

Political Diversity Will Improve Social Psychological Science1

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2015), Page 1 of 58 doi:10.1017/S0140525X14000430, e130 Political diversity will improve social psychological science1 José L. Duarte Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85281 [email protected] http://joseduarte.com Jarret T. Crawford Psychology Department, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ 08628 [email protected] http://crawford.pages.tcnj.edu/ Charlotta Stern Department of Sociology, Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, SE-10691 Stockholm, Sweden lotta.stern@sofi.su.se http://www2.sofi.su.se/∼lst/ Jonathan Haidt Stern School of Business, New York University, New York, NY 10012 [email protected] http://www.stern.nyu.edu/faculty/bio/jonathan-haidt Lee Jussim Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 [email protected] www.rci.rutgers.edu/∼jussim/ Philip E. Tetlock Psychology Department, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104 [email protected] http://www.sas.upenn.edu/tetlock/ Abstract: Psychologists have demonstrated the value of diversity – particularly diversity of viewpoints – for enhancing creativity, discovery, and problem solving. But one key type of viewpoint diversity is lacking in academic psychology in general and social psychology in particular: political diversity. This article reviews the available evidence and finds support for four claims: (1) Academic psychology once had considerable political diversity, but has lost nearly all of it in the last 50 years. (2) This lack of political diversity can undermine the validity of social psychological science via mechanisms such as the embedding of liberal values into research questions and methods, steering researchers away from important but politically unpalatable research topics, and producing conclusions that mischaracterize liberals and conservatives alike. -

Group Processes Donelson R

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book Jepson School of Leadership Studies chapters and other publications 2010 Group Processes Donelson R. Forsyth University of Richmond, [email protected] Jeni Burnette Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/jepson-faculty-publications Part of the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Forsyth, Donelson R., and Jeni Burnette. Advanced Social Psychology: The State of the Science. Edited by Roy F. Baumeister and Eli J. Finkel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. 495-534. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Jepson School of Leadership Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book chapters and other publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 14 Group Processes Donelson R. Forsyth and Jeni Burnette Social behavior is often group behavior. People are in many respects individuals seeking their personal, private objectives, yet they are also members of social collectives that bind members to one another. The tendency to join with others is perhaps the most important single characteristic of humans. The processes that take place within these groups influence, in fundamental ways, their mem bers and society-at-large. Just as the dynamic processes that occur in groups such as the exchange of information among members, leading and following, pressures put on members to adhere to the group's standards, shifts in friend~ ship alliances, and conflict and collaboration-change the group, so do they also change the group's members. -

Beyond Group-Level Explanations for the Failure of Groups to Solve Hidden

Group Processes & Intergroup Relations http://gpi.sagepub.com/ Beyond group-level explanations for the failure of groups to solve hidden profiles: The individual preference effect revisited Nadira Faulmüller, Rudolf Kerschreiter, Andreas Mojzisch and Stefan Schulz-Hardt Group Processes Intergroup Relations 2010 13: 653 originally published online 30 July 2010 DOI: 10.1177/1368430210369143 The online version of this article can be found at: http://gpi.sagepub.com/content/13/5/653 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Group Processes & Intergroup Relations can be found at: Email Alerts: http://gpi.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://gpi.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://gpi.sagepub.com/content/13/5/653.refs.html >> Version of Record - Sep 17, 2010 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Jul 30, 2010 What is This? Downloaded from gpi.sagepub.com at LMU Muenchen on June 13, 2013 G Group Processes & P Intergroup Relations I Article R Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 13(5) 653–671 © The Author(s) 2010 Beyond group-level explanations Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermission.nav for the failure of groups to solve DOI: 10.1177/1368430210369143 hidden profiles: The individual gpir.sagepub.com preference effect revisited Nadira Faulmüller,1 Rudolf Kerschreiter,2 Andreas Mojzisch,1 and Stefan Schulz-Hardt1 Abstract The individual preference effect supplements the predominant group-level explanations for the failure of groups to solve hidden profiles. Even in the absence of dysfunctional group-level processes, group members tend to stick to their suboptimal initial decision preferences due to preference-consistent evaluation of information.