Groupthink Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Link to Dissertation

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Ripening or rotting? Examining the temporal dynamics of team discussion and decision making in long-term teams. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Media, Technology, and Society By Ilya Gokhman EVANSTON, ILLINOIS September 2020 2 ABSTRACT More than a quarter century of research finds that teams often fail to make high-quality decisions. This literature is based on observing team decisions in one-off decision making episodes, when in reality, most teams work together for an extended period of time, making repeated decisions together. Do teams improve or decline on decision making effectiveness over time? To answer this question, this dissertation contributes three studies on team decision making, examining how the processes and outcomes of team decision making evolve over time. In order to study team decision making over time, one needs parallel and comparable tasks on which to observe process and performance. And so, Study 1 developed and validated five parallel hidden profile tasks that require teams to share unique information in order to identify the optimal solution from three options. Using this newly developed battery of tasks, Studies 2 and 3 used mixed-methods to understand team decision making over time in eight 4-person teams. Study 2 was quantitative, examining the discussion and decision quality of teams during multiple sequential decision making episodes. Study 3 was qualitative, exploring the conversational dynamics over time. Quantitative analysis found that teams show an initial increase and subsequent decrease in discussion and decision quality as they work together. -

Media Campaigns and Perceptions of Reality

2820 Media Campaigns and Perceptions of Reality Media Campaigns and Perceptions of Reality Rajiv N. Rimal Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Humans act, at least partly, on the basis of how they think others expect them to act. This means that humans have the capacity to know what others think or expect them to do. Some researchers have argued that understanding what others think is essential to social life and that successful human relationships depend on our ability to read the minds of others (Gavita 2005; → Symbolic Interaction). How good are we, though, at knowing what others think or expect us to do? Data show that there is often a negative correlation between our perceived ability to know what others are thinking and what they are actually thinking (Davis & Kraus 1997). In other words, those who are more confident about their ability to know what others are thinking are, in fact, less accurate, compared to those who are less confident. Accuracy, however, may not be important in this context because what we choose to do usually depends on our perceptions more strongly than on objective reality (→ Media and Perceptions of Reality; Social Perception). Most communication-based campaigns, at their core, have the central mission to change people’s perceptions of reality, whether that reality pertains to something external (such as a political issue, an organization, etc.) or internal (self-concept). For example, political campaigns seek to change people’s perceptions about a particular candidate or issue, commercial campaigns strive to alter people’s attitudes toward a product, and health campaigns seek to alter people’s perceptions about their self-image, ability, or self- worth, just to name a few (→ Advertisement Campaign Management; Election Campaign Communication; Health Campaigns, Communication in). -

Group Support and Cognitive Dissonance 1 I'ma

Group support and cognitive dissonance 1 I‘m a Hypocrite, but so is Everyone Else: Group Support and the Reduction of Cognitive Dissonance Blake M. McKimmie, Deborah J. Terry, Michael A. Hogg School of Psychology, University of Queensland Antony S.R. Manstead, Russell Spears, and Bertjan Doosje Department of Social Psychology, University of Amsterdam Running head: Group support and cognitive dissonance. Key words: cognitive dissonance, social identity, social support Contact: Blake McKimmie School of Psychology The University of Queensland Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia Phone: +61 7 3365-6406 Fax: +61 7 3365-4466 Group support and cognitive dissonance 2 [email protected] Abstract The impact of social support on dissonance arousal was investigated to determine whether subsequent attitude change is motivated by dissonance reduction needs. In addition, a social identity view of dissonance theory is proposed, augmenting current conceptualizations of dissonance theory by predicting when normative information will impact on dissonance arousal, and by indicating the availability of identity-related strategies of dissonance reduction. An experiment was conducted to induce feelings of hypocrisy under conditions of behavioral support or nonsupport. Group salience was either high or low, or individual identity was emphasized. As predicted, participants with no support from the salient ingroup exhibited the greatest need to reduce dissonance through attitude change and reduced levels of group identification. Results were interpreted in terms of self -

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated With

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated with the Bounded Confidence XY Model, Parameterized by Twitter Data Maksym Romenskyy Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK and Department of Mathematics, Uppsala University, Box 480, Uppsala 75106, Sweden Viktoria Spaiser School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Thomas Ihle Institute of Physics, University of Greifswald, Felix-Hausdorff-Str. 6, Greifswald 17489, Germany Vladimir Lobaskin School of Physics, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland (Dated: July 26, 2018) Multiple countries have recently experienced extreme political polarization, which in some cases led to escalation of hate crime, violence and political instability. Beside the much discussed presi- dential elections in the United States and France, Britain’s Brexit vote and Turkish constitutional referendum, showed signs of extreme polarization. Among the countries affected, Ukraine faced some of the gravest consequences. In an attempt to understand the mechanisms of these phe- nomena, we here combine social media analysis with agent-based modeling of opinion dynamics, targeting Ukraine’s crisis of 2014. We use Twitter data to quantify changes in the opinion divide and parameterize an extended Bounded-Confidence XY Model, which provides a spatiotemporal description of the polarization dynamics. We demonstrate that the level of emotional intensity is a major driving force for polarization that can lead to a spontaneous onset of collective behavior at a certain degree of homophily and conformity. We find that the critical level of emotional intensity corresponds to a polarization transition, marked by a sudden increase in the degree of involvement and in the opinion bimodality. -

'Everybody's Doing It': on the Persistence of Bad Social Norms

Experimental Economics (2020) 23:392–420 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-019-09616-z ORIGINAL PAPER ‘Everybody’s doing it’: on the persistence of bad social norms David Smerdon1 · Theo Oferman2 · Uri Gneezy3 Received: 5 July 2017 / Revised: 15 May 2019 / Accepted: 21 May 2019 / Published online: 31 May 2019 © Economic Science Association 2019 Abstract We investigate how information about the preferences of others afects the persis- tence of ‘bad’ social norms. One view is that bad norms thrive even when people are informed of the preferences of others, since the bad norm is an equilibrium of a coordination game. The other view is based on pluralistic ignorance, in which uncer- tainty about others’ preferences is crucial. In an experiment, we fnd clear support for the pluralistic ignorance perspective . In addition, the strength of social interac- tions is important for a bad norm to persist. These fndings help in understanding the causes of such bad norms, and in designing interventions to change them. Keywords Social norms · Pluralistic ignorance · Social interactions · Equilibrium selection · Conformity JEL Classifcation C92 · D70 · D90 · Z10 1 Introduction Social norms provide informal rules that govern our actions within diferent groups and societies and across all manner of situations. Many social norms develop in order to overcome market failure, mitigate negative externalities or promote positive We acknowledge the University of Amsterdam Behavior Priority Area for providing funding for the experiment. Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https ://doi.org/10.1007/s1068 3-019-09616 -z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. -

Exploring the Perception of Nationalism in the United States and Saudi Arabia Reem Mohammed Alhethail Eastern Washington University

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2015 Exploring the perception of nationalism in the United States and Saudi Arabia Reem Mohammed Alhethail Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.ewu.edu/theses Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Alhethail, Reem Mohammed, "Exploring the perception of nationalism in the United States and Saudi Arabia" (2015). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 330. http://dc.ewu.edu/theses/330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING THE PERCEPTION OF NATIONALISM IN THE UNITED STATES AND SAUDI ARABIA A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, WA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts in History By Reem Mohammed Alhethail Fall 2015 ii THESIS OF REEM MOHAMMED ALHETHAIL APPROVED BY DATE ROBERT SAUDERS, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE DATE MICHAEL CONLIN, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE DATE CHADRON HAZELBAKER, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE iii MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Eastern Washington University, I agree that (your library) shall make copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that copying of this project in whole or in part is allowable only for scholarly purposes. -

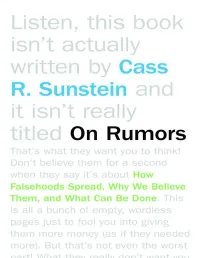

On Rumors Also by Cass R

On Rumors Also by Cass R. Sunstein Simpler: The Future of Government Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (with Richard Thaler) Worst-Case Scenarios Republic.com 2.0 Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge The Second Bill of Rights: Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Unfinished Revolution and Why We Need It More Than Ever Radicals in Robes: Why Extreme Right-Wing Courts Are Wrong for America Laws of Fear: Beyond the Precautionary Principle Why Societies Need Dissent Risk and Reason: Safety, Law, and the Environment One Case at a Time Free Markets and Social Justice Legal Reasoning and Political Conflict Democracy and the Problem of Free Speech The Partial Constitution After the Rights Revolution On Rumors How Falsehoods Spread, Why We Believe Them, and What Can Be Done Cass R. Sunstein With a new afterword by the author Princeton University Press • Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2014 by Cass R. Sunstein Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Originally published in North America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2009 First Princeton Edition 2014 ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-16250-8 LCCN 2013950544 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Printed on acid-free paper. -

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration Marina Lindell (Åbo Akademi University), André Bächtiger (University of Stuttgart), Kimmo Grönlund (Åbo Akademi University), Kaisa Herne (University of Tampere), Maija Setälä (University of Turku) Abstract In the study of deliberation, a largely underexplored area is why some participants become more extreme, whereas some become more moderate. Opinion polarization is usually considered a suspicious outcome of deliberation, while moderation is seen as a desirable one. This article takes issue with this view. Results from a deliberative experiment on immigration show that polarizers and moderators were not different in their socio-economic, cognitive, or affective profiles. Moreover, both polarization and moderation can entail deliberatively desired pathways: in the experiment, both polarizers and moderators learned during deliberation, levels of empathy were fairly high on both sides, and group pressures barely mattered. Finally, the absence of a participant with an immigrant background in a group was associated with polarization in anti-immigrant direction, bolstering longstanding claims regarding the importance of presence in interaction (Philips 1995). Paper presented at the “13ème Congrès National Association Française de Science Politique (AFSP), Aix-en-Provence, June 22–24, 2015 1 Introduction Empirical studies of citizen deliberation suggest that participants often change opinions (and also quite radically; see, e.g., Fishkin, 2009). Luskin et al. (2002) claim that knowledge gain is an important mechanism of opinion change, whereas Sanders (2012) was unable to identify any robust predictor of opinion change in a recent study based on a pan-European deliberative poll (Europolis). A largely understudied area in this regard is why some participants polarize their opinions due to deliberation, and why others moderate them. -

Affective Polarization and Its Impact on College Campuses

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2020 Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses Sam Rosenblatt Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Rosenblatt, Sam, "Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses" (2020). Honors Theses. 529. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/529 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN WE ALL JUST GET ALONG?: AFFECTIVE POLARIZATION AND ITS IMPACT ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES by Sam Rosenblatt A Thesis Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in Political Science April 3, 2020 Approved by: _____________________________________ Advisor: Chris Ellis _____________________________________ Department Chairperson: Scott Meinke Acknowledgements While the culmination of my honors thesis feels a bit anticlimactic as Bucknell has transitioned to remote education, I could not have accomplished this project without the help of the many faculty, friends, and family who supported me. To Professor Ellis, thank you for advising and guiding me throughout this process. Your advice was instrumental and I looked forward every week to discussing my progress and American politics with you. To Professor Meinke and Professor Stanciu, thank you for serving as additional readers. And especially to Professor Meinke for helping to spark my interest in politics during my freshman year. -

Pluralistic Ignorance Concerning Alcohol Usage Among Recent High School Graduates

Modern Psychological Studies Volume 3 Number 1 Article 5 1995 Pluralistic ignorance concerning alcohol usage among recent high school graduates Jill S. Braddock University of Evansville Tonia R. Wolf University of Evansville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Braddock, Jill S. and Wolf, Tonia R. (1995) "Pluralistic ignorance concerning alcohol usage among recent high school graduates," Modern Psychological Studies: Vol. 3 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol3/iss1/5 This articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals, Magazines, and Newsletters at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Psychological Studies by an authorized editor of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Till S. Braddock and Tonia R. Wolf Pluralistic Ignorance Concerning that expectations were more important in predicting an adolescent's drinking habits Alcohol Usage Among Recent than either background or demographic High School Graduates variables. Jill S. Braddock and Tonia R. Wolf Prentice and Miller (1993) conducted a study at Princeton University University of Evansville designed to test "pluralistic ignorance" in undergraduates' use of alcohol. They Abstract found pluralistic ignorance prevalent in the undergraduates' beliefs that they were Recent high school graduates in a mid- less comfortable with drinking alcohol western community estimated their than the average student. Thus, alcohol classmates' attitudes toward alcohol use use may play an integral role in campus in contrast to their own positions. life because everyone believes it to be the Attitudes were assessed on three levels: accepted norm, despite conflicting subjective comfort with others' drinking, personal sentiments. -

Pluralistic Ignorance Varies with Group Size∗ a Dynamic Model of Impression Management

Pluralistic Ignorance Varies With Group Size∗ A Dynamic Model of Impression Management Mauricio Fern´andezDuquey December 6, 2018 Abstract I develop a theory of group interaction in which individuals who act sequentially are `impression managers' concerned with signaling what they believe is the majority opin- ion. Equilibrium dynamics may result in most individuals acting according to what they mistakenly believe is the majority opinion, a situation known as `pluralistic ig- norance'. Strong ex ante beliefs over others' views increases pluralistic ignorance in small groups, but decreases it in large groups. Pluralistic ignorance may lead to a perverse failure of collective action, where individuals don't act selfishly because they incorrectly believe they are acting in a way that benefits others, which results in an inefficient drop in social interactions. A policymaker who wants to maximize social welfare will reveal information about the distribution of opinions in large groups, but will manipulate information to make the minority seems larger if the group is small. ∗The latest version of the paper can be found at https://scholar.harvard.edu/duque/research. I would like to thank Samuel Asher, Nava Ashraf, Robert Bates, Iris Bohnet, Jeffry Frieden, Benjamin Golub, Michael Hiscox, Antonio Jim´enez,Horacio Larreguy, Navin Kartik, Scott Kominers, Stephen Morris, Pia Raffler, Matthew Rabin, Kenneth Shepsle, Joel Sobel, and seminar participants at Harvard University, ITAM, CIDE, and the European Economic Association. yHarvard University and CIDE. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction When group members act according to what they think others want, they may end up doing what nobody wants. -

The Effects of Mentioning Information, Shared Information Bias, Ownership Bias, Reiteration, and Confirmation Bias Lyn M

Perceived Importance of Information: The Effects of Mentioning Information, Shared Information Bias, Ownership Bias, Reiteration, and Confirmation Bias Lyn M. van Swol To cite this version: Lyn M. van Swol. Perceived Importance of Information: The Effects of Mentioning Information, Shared Information Bias, Ownership Bias, Reiteration, and Confirmation Bias. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, SAGE Publications, 2007, 10 (2), pp.239-256. 10.1177/1368430207074730. hal-00571647 HAL Id: hal-00571647 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00571647 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2007 Vol 10(2) 239–256 Perceived Importance of Information: The Effects of Mentioning Information, Shared Information Bias, Ownership Bias, Reiteration, and Confi rmation Bias Lyn M. Van Swol Northwestern University Participants were given information for and against the decriminalization of marijuana and discussed the issue in groups. Factors affecting rated importance of information after the group discussion were examined. Participants did not rate information that was mentioned during the discussion as more important than information not mentioned, and participants did not rate shared information they mentioned as more important than unshared information.