The Myth of the Scapegoat in Newspaper Coverage Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Los Angeles and the 1984 Olympic Games

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Los Angeles and the 1984 Olympic Games: Cultural Commodification, Corporate Sponsorship, and the Cold War A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Josh R. Lieser December 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Catherine Gudis, Chairperson Dr. Molly McGarry Dr. Kiril Tomoff Copyright by Josh R. Lieser 2014 The Dissertation of Josh R. Lieser is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Los Angeles and the 1984 Olympic Games: Cultural Commodification, Corporate Sponsorship, and the Cold War by Josh R. Lieser Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in History University of California, Riverside, December 2014 Dr. Catherine Gudis, Chairperson The 1984 Olympics offer an unprecedented opportunity to consider the way that sports were used as cultural and ideological warfare or soft power in the late stages of the Cold War era. Despite the Soviet Union’s decision to boycott the Olympics in Los Angeles in 1984, the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics were a claimed “victory” by President Ronald Reagan in the Cultural Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. Los Angeles won the right to host the games, and was a politically prudent choice for the United States within the context of the Cultural Cold War. The complicated history of Los Angeles and its constructed post-WWII identity are important elements to the choice of Los Angeles as host city. The Soviet boycott of the 1984 Olympic Games by the Soviet Union is central to the buildup to 1984, but due to the financial success of the Games the Soviet absence was not the crisis that many predicted. -

Across the Universe? a Comparative Analysis of Violent Behavior And

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Across the Universe? A Comparative Analysis of Violent Behavior and Radicalization Across Three Offender Types with Implications for Criminal Justice Training and Education Author(s): John G. Horgan, Ph.D., Paul Gill, Ph.D., Noemie Bouhana, Ph.D., James Silver, J.D., Ph.D., Emily Corner, MSc. Document No.: 249937 Date Received: June 2016 Award Number: 2013-ZA-BX-0002 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this federally funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Across the Universe? A Comparative Analysis of Violent Behavior and Radicalization Across Three Offender Types with Implications for Criminal Justice Training and Education Final Report John G. Horgan, PhD Georgia State University Paul Gill, PhD University College, London Noemie Bouhana, PhD University College, London James Silver, JD, PhD Worcester State University Emily Corner, MSc University College, London This project was supported by Award No. 2013-ZA-BX-0002, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice 1 ABOUT THE REPORT ABOUT THE PROJECT The content of this report was produced by John Horgan (Principal Investigator (PI)), Paul Gill (Co-PI), James Silver (Project Manager), Noemie Bouhana (Co- Investigator), and Emily Corner (Research Assistant). -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

Managing a Multijurisdictional Case

80828_Cover R5 10/7/04 11:40 PM Page 1 Managing A Multijurisdictional Case GERARD R. MURPHY CHUCK WEXLER WITH HEATHER J. DAVIES MARTHA PLOTKIN 1120 Connecticut Avenue, NW Suite 930 Washington DC, 20036 Phone: 202-466-7820 Fax: 202-466-7826 www.policeforum.org 80828_i-200.R7 10/8/04 12:07 AM Page i Managing a Multijurisdictional Case: Identifying the Lessons Learned from the Sniper Investigation GERARD R. MURPHY AND CHUCK WEXLER WITH HEATHER J. DAVIES AND MARTHA PLOTKIN A Report Prepared by the Police Executive Research Forum for the Office of Justice Programs U.S. Department of Justice OCTOBER 2004 80828_i-200.R7 10/8/04 12:07 AM Page ii This project, conducted by the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), was supported by Cooperative Agreement #2003-DD-BX-0004 by the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs’ Bureau of Justice Assistance. Points of view or opinions contained in this document are those of the authors and do not necessar- ily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or the members of PERF. Websites and sources listed provide information useful at the time of this writing, but the authors do not endorse any information of the sponsor organization or other information on the websites. © Police Executive Research Forum, U.S. Department of Justice Police Executive Research Forum Washington, DC 20036 United States of America October 2004 ISBN: 1-878734-82-2 Library of Congress: 2004109330 Photos courtesy of AP Worldwide Photos and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Cover design and layout by Nelson Design Group, Inc. -

Anti-Choice Violence and Intimidation

Anti-Choice Violence and Intimidation A campaign of violence, vandalism, and intimidation is endangering providers and patients and curtailing the availability of abortion services. Since 1993, eight clinic workers – including four doctors, two clinic employees, a clinic escort, and a security guard – have been murdered in the United States.1 Seventeen attempted murders have also occurred since 1991.2 In fact, opponents of choice have directed more than 6,400 reported acts of violence against abortion providers since 1977, including bombings, arsons, death threats, kidnappings, and assaults, as well as more than 175,000 reported acts of disruption, including bomb threats and harassing calls.3 The Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act (FACE) provides federal protection against the unlawful and often violent tactics used by abortion opponents. Peaceful picketing and protest is not prohibited and is explicitly and fully protected by the law.4 State clinic protection laws in 16 states and the District of Columbia, as well as general statutes prohibiting violence, provide additional protection.5 Although the frequency of some types of clinic violence declined after the 1994 enactment of FACE, violence at reproductive-health centers is far from being eradicated.6 Vigorous enforcement of clinic-protection laws against those who use violence and threats is essential to protecting the lives and well-being of women and health-care providers. Abortion Providers and Other Health Professionals Face the Threat of Murder MURDERS: Since 1993, eight people have been murdered for helping women exercise their constitutionally protected right to choose.7 . 2009: The Murder of Dr. George Tiller. -

CBP Security Policy and Procedures Handbook HB1400-02B August 13, 2009

CBP Security Policy and Procedures Handbook HB1400-02B August 13, 2009 Security Never Sleeps FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY VOL TOC BACK VOLUME CONTENTS 1. FOREWORD ............................................................................V 2. REVISION HISTORY ...............................................................XVII 3. PHYSICAL SECURITY HANDBOOK.............................................VII 4. INFORMATION SECURITY: SAFEGUARDING CLASSIFIED AND SENSITIVE BUT UNCLASSIFIED INFORMATION HANDBOOK ... 735 5. BADGES, CREDENTIALS AND OFFICIAL IDENTIFICATION ............. 845 WARNING: This document is FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY (FOUO). It is to be controlled, stored, handled, transmitted, distributed, and disposed of in accordance with DHS policy relating to FOUO information. This information shall not be distributed beyond the original addressees without prior authorization of the originator. iii of 890 U.S. Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 20229 Commissioner FOREWORD The Office of Internal Affairs (IA) Security Management Division (SMD) is responsible for establishing policies, standards, and procedures to ensure the safety and security of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) personnel, facilities, information, and assets. IA/SMD has developed the CBP Security Policy and Procedures Handbook to provide CBP with uniform standards and procedures for the proper administration of Physical Security; Safeguarding Classified and Sensitive but Unclassified Information; and Badges, Credentials, and Official Identification.This handbook -

Introduction to Forensic Science

Introduction to Forensic Science Serial Killers I. Definition A. Serial murders - repetitive homicides, nearly always one-on-one murders, where the perpetrator is usually a stranger or has a slight acquaintance to the victim. (Historically, the majority of homicide victims knew their killer, but during the 1990's, this figure changed. Statistics from 1995's Uniform Crime Reports state that 55% of homicide victims have no known association with the perpetrators.1) The serial murderer’s motivation to kill is not based on crimes of passion, victim precipitation, personal gain or profit. Serial murderers are nearly always males prompted by sexual or aggressive drives to exert power through killing.2 B. Modus operandi - a characteristic pattern of behavior repeated in a series of offenses. The following are categories of modus operandi devised by Major L.W. Atcherley, an English constable in the 1800's. 1. Classword - the kind of property attacked, such as a house, a college dormitory, people parked in cars at lover's lanes 2. Entry - the point of entry, such as open bedroom windows, sliding glass doors 3. Means - implements or tools that were used, such as a pry bar, ladder, screw driver 4. Object - kind of property taken, such as bras and panties 5. Time - time of day or night, weekdays, non-work days, holidays (when people would not miss the perpetrator at work) 6. Style - the description the criminal gives the victim to gain entrance (plumber, cable TV repairman) 7. Tale - any disclosure the criminal makes as to his business/purpose 8. Pals - any co-conspirators 9. -

Is Only the Latest Film to Depict a Female Journalist Trading Sex for Scoops

12/12/2019 ‘Richard Jewell’ is only the latest film to depict a female journalist trading sex for scoops Help us in the fight for facts and science Donate Now Academic rigor, journalistic flair Actress Olivia Wilde plays reporter Kathy Scruggs in ‘Richard Jewell.’ Invision/AP Images/Jordan Strauss ‘Richard Jewell’ is only the latest film to depict a female journalist trading sex for scoops December 12, 2019 8.19am EST Critics have lambasted Clint Eastwood’s new biographical drama, “Richard Jewell,” Author over its depiction of female reporter Kathy Scruggs, who’s played by actress Olivia Wilde. During the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, security guard Richard Jewell saved Joe Saltzman countless lives after discovering a backpack filled with pipe bombs and alerting Professor of Journalism and police. The film tells the true story of how Jewell was unjustly vilified by the news Communication, University of Southern California, Annenberg School for media, which falsely reported that he was the terrorist. Communication and Journalism But at one point in the movie, Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Kathy Scruggs trades sex with an FBI agent for confidential information. According to the former colleagues of Scruggs, who died in 2001, this never happened. https://theconversation.com/richard-jewell-is-only-the-latest-film-to-depict-a-female-journalist-trading-sex-for-scoops-128673 1/4 12/12/2019 ‘Richard Jewell’ is only the latest film to depict a female journalist trading sex for scoops The filmmakers could have easily avoided the controversy by not including this detail. It’s not exactly a critical plot point. -

The Immediate and Gradual Impact of Terrorist Attacks on the Sports Events Industry

The immediate and gradual impact of terrorist attacks on the sports events industry Ayeisha Dsouza Introduction The Munich massacre at the Olympics of 1972 , the Centennial Olympic park explosion of 1996 at Atlanta , explosion near Bernabeu stadium in Madrid in 2002, suicide bomb attack against the New Zealand cricket team in 2002 in Pakistan and gunfire attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team in 2009 in Pakistan, suicide bomber attack at a marathon in Sri Lanka in 2008 , Boston Marathon bomb attack in 2013 (Galily et al , 2015), bomb attack outside Stade de France during a series of attacks in 2015 (Spaaij,2016) ,series of controlled explosions on the German football club Borussia Dortmund this year (The Wire, 2017) are instances of how sports events have been continuously targeted by terrorists. Before the Munich massacre of 1972, the main threat of sports events was hooligan behaviour but the increasing attack on sports events have put counterterrorism strategies to the forefront (Toohey et al, 2003). Sporting events of the 20th & 21st century have lost their innocence due to the activities of terrorist organisations and individuals Atkinson and Young, 2012). “There have been 168 terrorist attacks related to sport between 1972 and 2004” (Clark, Kennelly quoted 2004,2005 in Toohey et al, 2008, p 451) Contemporary terrorists prefer targets with dense gatherings and worldwide media coverage to spread their message and cause widespread trauma, sports events provide a perfect setting and are increasingly targeted by terrorists (Spaaij and Hamm,2015). Sports mega events also carry a symbolic and prestigious element and are used by host nations for the concept of nation branding (Gripsurd et al,2010). -

Guarding America: Security Guards and U.S. Critical Infrastructure Protection

Order Code RL32670 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Guarding America: Security Guards and U.S. Critical Infrastructure Protection November 12, 2004 Paul W. Parfomak Specialist in Science and Technology Resources, Science, and Industry Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Guarding America: Security Guards and U.S. Critical Infrastructure Protection Summary The Bush Administration’s 2003 National Strategy for the Physical Protection of Critical Infrastructures and Key Assets indicates that security guards are “an important source of protection for critical facilities.” In 2003, approximately one million security guards (including airport screeners) were employed in the United States. Of these guards, analysis indicates that up to 5% protected what have been defined as “critical” infrastructure and assets. The effectiveness of critical infrastructure guards in countering a terrorist attack depends on the number of guards on duty, their qualifications, pay and training. Security guard employment may have increased in certain critical infrastructure sectors since September 11, 2001, although overall employment of U.S. security guards has declined in the last five years. Contract guard salaries averaged $19,400 per year in 2003, less than half of the average salary for police and well below the average U.S. salary for all occupations. There are no U.S. federal requirements for training of critical infrastructure guards other than airport screeners and nuclear guards. Twenty-two states do require basic training for licensed security guards, but few specifically require counter-terrorism training. State regulations regarding criminal background checks for security guards vary. Sixteen states have no background check regulations. -

Ljubljana Residents' Knowledge of and Satisfaction with Private Security Guards' Work

VARSTVOSLOVJE, Journal of Criminal Ljubljana Residents’ Justice and Security, year 21 no. 4 Knowledge of and Satisfaction pp. 366‒381 with Private Security Guards’ Work Lavra Horvat, Matevž Bren, Andrej Sotlar Purpose: The purpose of the paper was to present out how Ljubljana residents know, understand and evaluate the work of private security guards. Design/Methods/Approach: A survey by internet and telephone was conducted among Ljubljana residents. The sample included residents between 18 and 75 years of age. A combined weights method was used in order to assure the representativeness of the sample by gender and age. Findings: Residents of Ljubljana are satisfied with the work performed by private security guards. Residents’ satisfaction mainly depends on their trust in security guards’ work, the help and assistance provided by security guards, security guards’ attitude towards residents and residents’ experience with security guards’ work. Residents assess their work as stressful and dangerous, however, they still believe that security guards lack education and professionalism, which is a finding, common to many other studies. Research Limitations/Implications: The survey is limited to the Ljubljana area, so a similar survey should be carried out nationwide. Practical Implications: Findings could be used by private security companies to plan adequate processes of training, professional socialisation and public relations strategies, thus increasing the degree of security guards’ professionalism. In turn, the improved professionalism would contribute greatly to a more positive assessment of security guards by residents. Originality/Value: In Slovenia, this kind of survey was conducted for the first time among the general population, as so far similar surveys have been carried out mainly among the student population. -

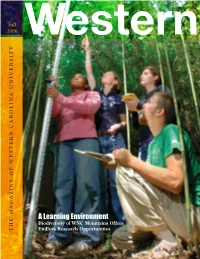

A Learning Environment Biodiversity of WNC Mountains Offers

Western 2006 Fall THE MAGAZINE O F W E S T ERN CAROLINA UNIVERSI T Y Endless Research Opportunities Biodiversity ofWNC MountainsOffers A LearningEnvironment Tackling the Tube Catamount fans across the Southeast who can’t make it to the Saturday, Sept. 23, football game at Furman or to the Homecoming showdown with Chattanooga still can have front row seats. Both games are scheduled to be broadcast by ComCast/Charter Sports Southeast (CSS) for cable subscribers in 12 states —Arkansas, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. WLOS/WYMA of Asheville, which is donating the uplink and satellite time for the WCU-Furman game, will carry a replay on Sunday, Sept. 24, at 2 p.m. Negotiations also are under way to televise the annual Battle for the Old Mountain Jug when Appalachian State returns to Cullowhee on Nov. 11. For updates on the televised games or a complete fall athletics schedule, visit catamountsports.com. Western THE MAGAZINE OF WES T ERN CAROLINA UNIVERSI T Y Fall 2006 Volume 10, No. 3 Cover Story Western Carolina University Magazine, formerly known as Our Purple and Gold, is produced by the Office of Outdoors Odyssey Public Relations in the Division of Advancement and WNC Mountains Take External Affairs for alumni, faculty, staff, friends and 8 students of Western Carolina University. Students Above and Beyond (on the cover) Kathy Mathews, assistant professor of biology, Chancellor John W. Bardo points out aspects of rivercane to Western students Sharhonda Bell, Katie McDowell and Adam Griffith (from Vice Chancellor Clifton B.