Towards a Social Ontology of Improvised Sound Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 8.Indd

Issue #8 Save The Crumbs What You’re Reading... Save The Crumbs is an independent ‘zine written, designed, assembled and distributed by a handful of people in Mankato who think they have something to say. We started this publication because we feel the spirit of “do it yourself” is lacking in Mankato and the surrounding areas. Save The Crumbs is a collection of writings, musings, opinions, reviews, observations, artwork, and basically anything we want to print. Save The Crumbs is the true spirit of D.I.Y. No advertisements. No corporate pressure. No creativity-stifling forces. No “The Man.” So, grab a copy of this thing and show it to your friends. Lend it to people. Make copies of it at your place of employment. Get the word out. Be inspired. Make your own ‘zine! If you have any questions, comments, advice, or want to submit something… send e-mail to [email protected]. If you can’t secure your own copy of this issue, be sure to go to www.myspace.com/savethecrumbs to check out the online version. CONTRIBUTERS: Dustin Wilmes, John Maiers, Juston Cline, Joe Eggen, Sadie Arch, Morgan Lust, Britta Moline, Dave Perron, Dylan Schultz, Monsieur Triste, Sarah Turbes, Melissa Windom From the Angry Desk of Juston Cline... Dear Everybody, What is the deal? Why is it that so many people have decided in themselves that going to a bar, getting drunk, and having sex is the pinnacle of life? I mean, of course there are those who would rather get drunk and have sex at a party than at the bar. -

Making Our Own—Two Ethnographies of the Vernacular in New Zealand Music: Tramping Club Singsongs and the Māori Guitar Strumming Style

Making our own—two ethnographies of the vernacular in New Zealand music: tramping club singsongs and the Māori guitar strumming style by Michael Brown A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington/Massey University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music New Zealand School of Music 2012 ii Abstract This work presents two ethnographies of the vernacular in New Zealand music. The ethnographies are centred on the Wellington region, and deal respectively with tramping club singsongs and the Māori guitar strumming style. As the first studies to be made of these topics, they support an overall argument outlined in the Introduction, that the concept of ―vernacular‖ is a valuable way of identifying and understanding some significant musical phenomena hitherto neglected in New Zealand music studies. ―Vernacular‖ is conceptualised as an informal, homemade approach that enables people to customise music-making, just as language is casually manipulated in vernacular speech. The different theories and applications which contribute to this perspective, taken from music studies and other disciplines, are examined in Chapter 1. A review of relevant New Zealand music literature, along with a methodological overview of the ethnographies is presented in Chapter 2. Each study is based upon different mixtures of techniques, including participant-observer fieldwork, oral history, interviews, and archival research. They can be summarised as follows: Tramping club singsongs: a medium of informal self-entertainment among New Zealand wilderness recreationists in the mid-twentieth century. The ethnography focuses on two clubs in the Wellington region, the Tararua Tramping Club and the Victoria University College Tramping Club, during the 1940s-1960s period, when changing social mores, tramping‘s camaraderie and individualism, and the clubs‘ different approaches, gave their singsongs a distinctive character. -

Fiona Hall Medicine Bundle for the Non-Born Child (Detail) 1994

Bulletin Summer Christchurch Art Gallery December 2008 — B.155 Te Puna o Waiwhetu February 2009 1 Bulletin B.155 Summer Christchurch Art Gallery December 2008 — Te Puna o Waiwhetu February 2009 Two cyclists use the custom-designed bikes that form Anne Veronica Janssens's Les Australoïdes installation in the Gallery foyer. Front and back cover images: Fiona Hall Medicine bundle for the non-born child (detail) 1994. Aluminium, rubber, plastic layette comprising matinee jacket. Collection of Queensland Art Gallery, purchased 2000. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney 2 3 Contents B.155 4 DIRECTOR'S FOREWORD A few words from director Jenny Harper 5 EXHIBITIONS PROGRAMME What's on at the Gallery this season 6 FIONA HALL: FORCE FIELD Paula Savage on one of Australia's finest contemporary artists 15 LOOKING INTO FORCE FIELD Two personal responses 16 SHOWCASE Recent gifts to the Gallery's collection 18 WUNDERBOX A collection of collections from the collection 26 THE ART OF COLLECTING Four artists show us their personal collections 30 LET IT BE NOW Six emerging Canterbury artists 34 WHITE ON WHITE Exploring the myriad possibilities of white 42 OUTER SPACES Richard Killeen takes his art out to the street 44 LONG WIRES IN DARK An interview with MUSEUMS Alastair Galbraith 46 ARE YOU TALKING TO ME? Jim and Mary Barr on collecting 47 PAGEWORK #1 Eddie Clemens 50 TE HURINGA / Pākehā colonisation TURNING POINTS and Māori empowerment 56 SCAPE 2008 Looking back at some of the Gallery projects 58 MY FAVOURITE Film-maker Gaylene Preston makes her choice 60 TIME-LAPSE Installing United We Fall 62 NOTEWORTHY News bites from around the Gallery 64 STAFF PROFILE Martin Young 64 COMING SOON Previewing Rita Angus: Life & Vision and Miles: a life in architecture Please note: The opinions put forward in this magazine are not necessarily those of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu. -

MAKING MAORI AD 1000-1200 1642 1769 ENTER EUROPE 1772 1790S

© Lonely Planet Publications 30 lonelyplanet.com HISTORY •• Enter Europe 31 THE MORIORI & THEIR MYTH History James Belich One of NZ’s most persistent legends is that Maori found mainland NZ already occupied by a more peaceful and racially distinct Melanesian people, known as the Moriori, whom they exterminated. New Zealand’s history is not long, but it is fast. In less than a thousand One of NZ’s foremost This myth has been regularly debunked by scholars since the 1920s, but somehow hangs on. years these islands have produced two new peoples: the Polynesian Maori To complicate matters, there were real ‘Moriori’, and Maori did treat them badly. The real modern historians, James and European New Zealanders. The latter are often known by their Maori Belich has written a Moriori were the people of the Chatham Islands, a windswept group about 900km east of the name, ‘Pakeha’ (though not all like the term). NZ shares some of its history mainland. They were, however, fully Polynesian, and descended from Maori – ‘Moriori’ was their number of books on NZ with the rest of Polynesia, and with other European settler societies, but history and hosted the version of the same word. Mainland Maori arrived in the Chathams in 1835, as a spin-off of the has unique features as well. It is the similarities that make the differences so Musket Wars, killing some Moriori and enslaving the rest (see the boxed text, p686 ). But they TV documentary series interesting, and vice versa. NZ Wars. did not exterminate them. The mainland Moriori remain a myth. -

Hearing Ourselves: Globalisation, the State, Local Content and New Zealand Radio

HEARING OURSELVES: GLOBALISATION, THE STATE, LOCAL CONTENT AND NEW ZEALAND RADIO A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology at the University of Canterbury by Zita Joyce University of Canterbury 2002 ii Abstract _____________________________________________________________________ Local music content on New Zealand radio has increased markedly in the years between 1997, when content monitoring began, and January 2002. Several factors have contributed to this increase, including a shift in approach from musicians themselves, and the influence of a new generation of commercial radio programmers. At the heart of the process, however, are the actions of the New Zealand State in the field of cultural production. The deregulation of the broadcasting industry in 1988 contributed to an apparent decline in local music content on radio. However, since 1997 the State has attempted to encourage development of a more active New Zealand culture industry, including popular music. Strategies directed at encouraging cultural production in New Zealand have positioned popular music as a significant factor in the development and strengthening of ‘national’ or ‘cultural’ identity in resistance to the cultural pressures of globalisation. This thesis focuses on the issue of airtime for New Zealand popular music on commercial radio, and examines the relationship between popular music and national identity. The access of New Zealand popular music to airtime on commercial radio is explored through analysis of airplay rates and other music industry data, and a small number of in-depth interviews with radio programmers and other people active in the industry. A considerable amount of control over the kinds of music supported and produced in New Zealand lies with commercial radio programmers. -

Newslist Drone Records 31. January 2009

DR-90: NOISE DREAMS MACHINA - IN / OUT (Spain; great electro- acoustic drones of high complexity ) DR-91: MOLJEBKA PVLSE - lvde dings (Sweden; mesmerizing magneto-drones from Swedens drone-star, so dense and impervious) DR-92: XABEC - Feuerstern (Germany; long planned, finally out: two wonderful new tracks by the prolific german artist, comes in cardboard-box with golden print / lettering!) DR-93: OVRO - Horizontal / Vertical (Finland; intense subconscious landscapes & surrealistic schizophrenia-drones by this female Finnish artist, the "wondergirl" of Finnish exp. music) DR-94: ARTEFACTUM - Sub Rosa (Poland; alchemistic beauty- drones, a record fill with sonic magic) DR-95: INFANT CYCLE - Secret Hidden Message (Canada; long-time active Canadian project with intelligently made hypnotic drone-circles) MUSIC for the INNER SECOND EDITIONS (price € 6.00) EXPANSION, EC-STASIS, ELEVATION ! DR-10: TAM QUAM TABULA RASA - Cotidie morimur (Italy; outerworlds brain-wave-music, monotonous and hypnotizing loops & Dear Droners! rhythms) This NEWSLIST offers you a SELECTION of our mailorder programme, DR-29: AMON – Aura (Italy; haunting & shimmering magique as with a clear focus on droney, atmospheric, ambient music. With this list coming from an ancient culture) you have the chance to know more about the highlights & interesting DR-34: TARKATAK - Skärva / Oroa (Germany; atmospheric drones newcomers. It's our wish to support this special kind of electronic and with a special touch from this newcomer from North-Germany) experimental music, as we think its much more than "just music", the DR-39: DUAL – Klanik / 4 tH (U.K.; mighty guitar drones & massive "Drone"-genre is a way to work with your own mind, perception, and sub bass undertones that evoke feelings of total transcendence and (un)-consciousness-processes. -

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award Crafting Aotearoa: Protest Tautohetohe: A Cultural History of Making Objects of Resistance, The New Zealand Book Awards Trust has immense in New Zealand and the Persistence and Defiance pleasure in presenting the 16 finalists in the 2020 Wider Moana Oceania Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams, Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, the country’s Puawai Cairns Karl Chitham, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Published by Te Papa Press most prestigious awards for literature. Damian Skinner Published by Te Papa Press Bringing together a variety of protest matter of national significance, both celebrated and Challenging the traditional categorisations The Trust is so grateful to the organisations that continue to share our previously disregarded, this ambitious book of art and craft, this significant book traverses builds a substantial history of protest and belief in the importance of literature to the cultural fabric of our society. the history of making in Aotearoa New Zealand activism within Aotearoa New Zealand. from an inclusive vantage. Māori, Pākehā and Creative New Zealand remains our stalwart cornerstone funder, and The design itself is rebellious in nature Moana Oceania knowledge and practices are and masterfully brings objects, song lyrics we salute the vision and passion of our naming rights sponsor, Ockham presented together, and artworks to Residential. This year we are delighted to reveal the donor behind the acknowledging the the centre of our influences, similarities enormously generous fiction prize as Jann Medlicott, and we treasure attention. Well and divergences of written, and with our ongoing relationships with the Acorn Foundation, Mary and Peter each. -

Jorgensen 2019 the Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of the Stones

Sound Scripts Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 12 2019 The eS mi-Autonomous Rock Music of The tS ones Darren Jorgensen University of Western Australia Recommended Citation Jorgensen, D. (2019). The eS mi-Autonomous Rock Music of The tS ones. Sound Scripts, 6(1). Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/soundscripts/vol6/iss1/12 This Refereed Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/soundscripts/vol6/iss1/12 Jorgensen: The Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of The Stones The Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of The Stones by Darren Jorgensen1 The University of Western Australia Abstract: The Flying Nun record the Dunedin Double (1982) is credited with having identified Dunedin as a place where independent, garage style rock and roll was thriving in the early 1980s. Of the four acts on the double album, The Stones would have the shortest life as a band. Apart from their place on the Dunedin Double, The Stones would only release one 12” EP, Another Disc Another Dollar. This essay looks at the place of this EP in both Dunedin’s history of independent rock and its place in the wider history of rock too. The Stones were at first glance not a serious band, but by their own account, set out to do “everything the wrong way,” beginning with their name, that is a shortened but synonymous version of the Rolling Stones. However, the parody that they were making also achieves the very thing they set out to do badly, which is to make garage rock. Their mimicry of rock also produced great rock music, their nonchalance achieving that quality of authentic expression that defines the rock attitude itself. -

Dunedin Sound Sources at the Hocken Collections

Reference Guide Dunedin Sound Sources at the Hocken Collections ‘Thanks to NZR Look Blue Go Purple + W.S.S.O.E.S Oriental Tavern 22-23 Feb’, [1985]. Bruce Russell Posters, Hocken Ephemera Collection, Eph-0001-ML-D-07/09. (W.S.S.O.E.S is Wreck Small Speakers on Expensive Stereos). Permission to use kindly granted by Lesley Paris, Norma O’Malley, Denise Roughan, Francisca Griffin, and Kath Webster. Hocken Collections/ Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago Library Nau Mai Haere Mai ki Te Uare Taoka o Hākena: Welcome to the Hocken Collections He mihi nui tēnei ki a koutou kā uri o kā hau e whā arā, kā mātāwaka o te motu, o te ao whānui hoki. Nau mai, haere mai ki te taumata. As you arrive We seek to preserve all the taoka we hold for future generations. So that all taoka are properly protected, we ask that you: place your bags (including computer bags and sleeves) in the lockers provided leave all food and drink including water bottles in the lockers (we have a researcher lounge off the foyer which everyone is welcome to use) bring any materials you need for research and some ID in with you sign the Readers’ Register each day enquire at the reference desk first if you wish to take digital photographs Beginning your research This guide gives examples of the types of material relating to the Dunedin Sound held at the Hocken. All items must be used within the library. As the collection is large and constantly growing not every item is listed here, but you can search for other material on our Online Public Access Catalogues: for books, theses, journals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and audiovisual material, use Library Search|Ketu. -

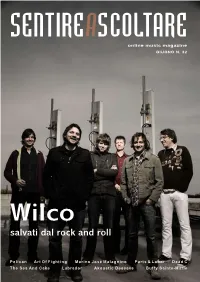

Salvati Dal Rock and Roll

SENTIREASCOLTARE online music magazine GIUGNO N. 32 Wilco salvati dal rock and roll Hans Appelqvist King Kong Laura Veirs Valet Keren Ann Feist Low PelicanStars Of The Art Lid Of Fighting Smog I Nipoti Marino del CapitanoJosé Malagnino Cristina Zavalloni Parts & Labor Billy Nicholls Dead C The Sea And Cake Labrador Akoustic Desease Buffys eSainte-Marie n t i r e a s c o l t a r e WWW.AUDIOGLOBE.IT VENDITA PER CORRISPONDENZA TEL. 055-3280121, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] DISTRIBUZIONE DISCOGRAFICA TEL. 055-328011, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] MATTHEW DEAR JENNIFER GENTLE STATELESS “Asa Breed” “The Midnight Room” “Stateless” CD Ghostly Intl CD Sub Pop CD !K7 Nuovo lavoro per A 2 anni di distan- Matthew Dear, uno za dal successo di degli artisti/produt- critica di “Valende”, È pronto l’omonimo tori fra i più stimati la creatura Jennifer debutto degli Sta- del giro elettronico Gentle, ormai nelle teless, formazione minimale e spe- sole mani di Mar- proveniente da Lee- rimentale. Con il co Fasolo, arriva al ds. Guidata dalla nuovo lavoro, “Asa Breed”, l’uomo di Detroit, si nuovo “The Midnight Room”, sempre su Sub voce del cantante Chris James, voluto anche rivela più accessibile che mai. Sì certo, rima- Pop. Registrato presso una vecchia e sperduta da DJ Shadow affinché partecipasse alle regi- ne il tocco à la Matthew Dear, ma l’astrattismo casa del Polesine ed ispirato forse da questa strazioni del suo disco, la formazione inglese usuale delle sue produzioni pare abbia lasciato sinistra collocazione, il nuovo album si districa mette insieme guitar sound ed elettronica, ri- uno spiraglio a parti più concrete e groovy. -

2015 Interview.Pdf

Interview from Spew, #87 February 2015 (originally published in abridged form) 2014’s triple disc behemoth Harshest Realm is the self-titled debut release of a musical project spearheaded by one Garret Kriston, a Chicago based musician whose formative years were split between formal studies and basement recording before toiling within the city’s DIY/punk scene. Now he has emerged with a sprawling document of what surely is a vast arsenal of artistic capabilities. Harshest Realm is now available via Coolatta Lounge CDs, along with fellow traveler Marshall Stacks’s latest jammers Lost in Sim City and the Snake Eyes/Point Blank single. ___________________________________________ Let’s start by giving the folks at home some background information. I’m particularly interested in learning how your relationship with music has developed over the years, so as to better understand where the music on the Harshest Realm album came from. No problem. I’m going to not hold back from rattling off influences and favorites, if that’s okay. Totally. The more the merrier. I was born at home on March 3rd, 1990 in Oak Park, down the street from Chicago’s west side, near Harlem between Harrison and Roosevelt. My earliest memory of music was seeing archival footage of The Beatles playing on the Ed Sullivan Show, which made playing guitar in a band and singing original songs seem like the most appealing activity in existence. I might have been two going on three, and I don’t remember much else from then besides puking in my crib and seeing carrots in it (the puke.) My older brother was discovering “classic rock,” so there were rock related bootleg VHS tapes in the house that would get played over and over. -

Te Oro O Te Ao the Resounding of the World

Te Oro o te Ao The Resounding of the World Rachel Mary Shearer 2018 An exegesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art and Design 1 2 ABSTRACT criteria of ihi—in this context, the intrinsic power of an event that draws a re- sponse from an audience, along with wehi—the reaction from an audience to this intrinsic power, and wana—the aura that occurs during a performance that encompasses both performer and audience, contribute to a series of sound events that aim at evocation or affect rather than interpretable narratives, stories or closed meanings. The final outcome of this research is realised as a sound installation, an exegesis and a 12” vinyl LP. Together these sound practices form a research-led practice document that demonstrates how and why listening to the earth matters, and pro- poses a multi-knowledge framework for understanding sound, space and environ- ment. Nō reira And so Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā tātou katoa Greetings, greetings, greetings to us all Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā tātou katoa Greetings, greetings, greetings to us all This practice-led PhD is a situated Pacific response to international critical dia- logues around materiality in the production and analysis of sonic arts. At the core of this project is the problem of what happens when questions asked in contexts of Pākehā knowledge frameworks are also asked within Māori knowledge frameworks. I trace personal genealogical links to Te Aitanga ā Māhaki, Rongowhakaata and Ngāti Kahungunu iwi.