Role of Natural and Anthropogenic Habitats in Conservation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keralda/India) Ecology and Landscape in an Isolated Indian National Park Photos: Ian Lockwood

IAN LOCKWOOD Eravikolam and the High Range (Keralda/India) Ecology and Landscape in an Isolated Indian National Park Photos: Ian Lockwood The southern Indian state of Kerala has long been recognized for its remarkable human development indicators. It has the country’s highest literary rates, lowest infant mortality rates and highest life expectancy. With 819 people per km2 Kerala is also one of the densest populated states in India. It is thus surprising to find one of the India’s loneliest and least disturbed natural landscapes in the mountainous region of Kerala known as the High Range. Here a small 97 km2 National Park called Eraviku- lam gives a timeless sense of the Western Ghats before the widespread encroachment of plantation agriculture, hydro- electric schemes, mining and human settlements. he High Range is a part of the Western Ghats, a heterogeneous chain of mountains and hills that separate the moist Malabar and Konkan Coasts from the semi-arid interiors of the TDekhan plateau. They play a key role in direct- ing the South Western monsoon and providing water to the plateau and the coastal plains. Starting at the southern tip of India at Kanyakumari (Cape Comorin), the mountains rise abruptly from the sea and plains. The Western Ghats continue in a nearly unbroken 1,600 km mountainous spine and end at the Tapi River on the border between Maharashtra and Gujarat. Bio- logically rich, the Western Ghats are blessed with high rates of endemism. In recent years as a global alarm has sounded on declining biodiversity, the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka have been designated as one of 25 “Global Biodiversity Hotspots” by Conservation Inter- national. -

The Four Iron Steamships of William Alexander Lewis Stephen Douglas – Hamilton

The Four Iron Steamships of William Alexander Lewis Stephen Douglas – Hamilton. KT 12th Duke of Hamilton, 9th Duke of Brandon, 2nd Duke of Châtellerault Second Edition. 1863 Easton Park, Suffolk, England (Demolished 1925) Hamilton Palace, Scotland (Demolished 1927) Brian Boon & Michel Waller Introduction The families residing in the village of Easton, Suffolk experienced many changing influences over their lives during the 92 year tenure of four generations of the Hamilton family over the 4,883 acre Easton Park Estate. The Dukes of Hamilton were the Premier Dukedom of Scotland, owning many mansions and estates in Scotland together with other mining interests. These generated considerable income. Hamilton Palace alone, in Scotland, had more rooms than Buckingham Palace. Their fortunes varied from the extremely wealthy 10th Duke Alexander, H.M. Ambassador to the Court of the Czar of Russia, through to the financial difficulties of the 12th Duke who was renowned for his idleness, gambling and luxurious lifestyle. Add to this the agricultural depression commencing in 1870. On his death in 1895, he left debts of £1 million even though he had previously sold the fabulous art and silver collections of his grandparents. His daughter, Mary, then aged 10 inherited Easton and the Arran estates and remained in Easton, with the Dowager Duchess until 1913 when she married Lord Graham. The estates were subsequently sold and the family returned to Arran. This is an account of the lives of the two passenger paddle steamers and two large luxury yachts that the 12th Duke had built by Blackwood & Gordon of Port Glasgow and how their purchase and sales fitted in with his varying fortunes and lifestyle. -

Strategies to Combat Man-Animal Conflicts

Horticulture International Journal Research Article Open Access Strategies to combat man-animal conflicts Abstract Volume 2 Issue 3 - 2018 Over a period of time, Human Population pressure has resulted in conversion of forest Sekhar C,1 Vidhyavathi A,1 Baranidharan K2 wildlife habitat into tea estates, tea factories and change in the land use is visualized. 1 This is evident in reduction of dense forest area where more number of wild lives has Department of Agricultural Economics, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, India their food, shelter, breeding and water requirements. There were so many streams, 2Department of Forestry, Forest College and Research Institute, pools, source of river and tributaries. Currently they were extinct from the scene and India animals for want of food, water and other requirements started migrating to the farm environment or near to the water hole. During these journeys, human and the animal Correspondence: Sekhar C, Professor, Department of conflicts become visualized resulted in more number of deaths and injuries. On an Agricultural Economics, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, average, every year two human deaths and many injuries are occurring. For that the Coimbatore, 641 003, India, Email [email protected] forest department has paid 123 lakhs of Rupees as compensation for affected victims. The affected individuals are migrated personnel to the forest floor for employment and Received: March 08, 2018 | Published: May 02, 2018 other purposes. Whereas, the tribes were not affected. The main reason is the people migrate to forest floor are not aware on the animal behavior, movement and hence awareness creation exercise found to be the principal strategy to the human to avoid the conflicts. -

General Theory Considered As Cultural Capital

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) JITTA JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY THEORY AND APPLICATION THE SOCIAL AND ACADEMIC STANDING OF THE INFORMATION SYSTEMS DISCIPLINE: GENERAL THEORY CONSIDERED AS CULTURAL CAPITAL DOUGLAS HAMILTON, Monash University P.O. Box 197, Caulfield East, Victoria 3145, Australia, Tel: 61 3 9903 1081, Fax: 61 3 9903 2205 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Bourdieu’s concepts of social fields and social power provide a theoretical basis for arguing that the information systems (IS) field is engaged in an ongoing struggle with other disciplines for prestige and support. While IS has produced a considerable amount of high quality theory and research, it is by no means clear that this is understood by either the academy or the general public. It is argued that the discipline’s profile could be raised by the development and promulgation of a general theory of IS, similar in scope to the general theories found in other disciplines such as sociology. The political and cultural value of developing such a theory is discussed, as are a range of issues it is recommended that it should address. INTRODUCTION item of “cultural capital” (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992) contributing to its public It is proposed in this paper that the image. An influential theory is implicitly a development of a prestigious general theory in statement that the field from which it the information systems (IS) field is possible, originates is a source of marketable ideas, and opportune, and would be of considerable worthy therefore of interest and respect benefit to the field. -

63. 2008 Annual Report

ASX Announcement 9 July 2008 Company Announcements Office Australian Stock Exchange Limited Exchange Centre Level 4 20 Bridge Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Sir, 2008 ANNUAL REPORT Please find attached the printed Annual Report for the year ended 31st March 2008 which is being mailed to shareholders, and available for downloading from the company website www.pmsgroup.com.au . Yours sincerely, PROGRAMMED MAINTENANCE SERVICES LIMITED Ian H. Jones Secretary For personal use only For personal use only Property Maintenance branch location Workforce branch location Facilities Management contract location Marine branch location NOTE: Capital cities have multiple branch locations CONTENTSBRANCH NETWORK For personal use only CONTENTS PART 1 PART 2 Highlights PAGE 2 Directors’ Report PAGE 19 Results in Brief PAGE 3 Income Statement PAGE 28 Our Company PAGE 4 Balance Sheet PAGE 29 Chairman’s Letter PAGE 6 Statement of Recognised Income & Expense PAGE 30 Managing Director’s Review PAGE 8 Cash Flow Statement PAGE 30 Board of Directors PAGE 10 Notes to the Financial Statements PAGE 31 Review of Operations PAGE 12 Directors’ Declaration PAGE 76 Corporate Social Responsibility PAGE 16 Independent Audit Report PAGE 77 Corporate Directory BACK COVER Auditor’s Independence Declaration PAGE 78 Statement of Corporate Governance PAGE 79 Additional Stock Exchange Information PAGE 82 Summary of Financial Statistics PAGE 83 For personal use only PRG Annual Report 2008 1 HIGHLIGHTS - 10th year of consecutive growth in revenue and earnings Revenue* Up 163.4% - Successful merger with Integrated Group Year ended 31 March 2008 877.0m Year ended 31 March 2007 333.0m EBIT* Up 40.2% Year ended 31 March 2008 54.4m Year ended 31 March 2007 38.8m Net Profi t after Tax* Up 26.9% Year ended 31 March 2008 28.4m Year ended 31 March 2007 22.4m Dividends per Share Final: 10.5c per share fully franked (payable 24 July 2008) total for the 2008 year of 20 cents per share fully franked. -

The Heraldry of the Hamiltons

era1 ^ ) of t fr National Library of Scotland *B000279526* THE Heraldry of the Ibamiltons NOTE 125 Copies of this Work have been printed, of which only 100 will be offered to the Public. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/heraldryofhamilsOOjohn PLATE I. THE theraldry of m Ibamiltons WITH NOTES ON ALL THE MALES OF THE FAMILY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE ARMS, PLATES AND PEDIGREES by G. HARVEY JOHNSTON F.S.A., SCOT. AUTHOR OF " SCOTTISH HERALDRY MADE EASY," ETC. *^3MS3&> W. & A. K. JOHNSTON, LIMITED EDINBURGH AND LONDON MCMIX WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR. circulation). 1. "THE RUDDIMANS" {for private 2. "Scottish Heraldry Made Easy." (out print). 3. "The Heraldry of the Johnstons" of {only a few copies remain). 4. "The Heraldry of the Stewarts" Douglases" (only a few copies remain). 5. "The Heraldry of the Preface. THE Hamiltons, so far as trustworthy evidence goes, cannot equal in descent either the Stewarts or Douglases, their history beginning about two hundred years later than that of the former, and one hundred years later than that of the latter ; still their antiquity is considerable. In the introduction to the first chapter I have dealt with the suggested earlier origin of the family. The Hamiltons were conspicuous in their loyalty to Queen Mary, and, judging by the number of marriages between members of the different branches, they were also loyal to their race. Throughout their history one hears little of the violent deeds which charac- terised the Stewarts and Douglases, and one may truthfully say the race has generally been a peaceful one. -

Hugh Douglas HAMILTON II Named Sitters

Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800 Online edition HAMILTON, Hugh Douglas Dublin 1740–1808 Part II: Named sitters F–L J.375.1331 Mme Hendrik FAGEL, née Agneta Margaretha Catharina Boreel (1771–1824), pstl/ppr, 24x19.5 ov., sd → “HH ft Roma 1789” (Dutch PC; olim dep.: Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, inv. B3250). Exh.: Amsterdam 2018, h.c. ϕ J.375.1339 ~pendant: Countess of FARNHAM [?née ?Grace Burdett (1734–1816)], in a blue dress, pstl, pencil/ppr, 22.5x17.5 ov. (London, Christie’s, 21.III.1989, Lot 93, £1100; Leger Galleries 1995. London, Sotheby’s, 25.XI.1999, Lot 4 repr., with pendant n.r., est. £1000–1500; London, Sotheby’s, 18.V.2001, Lot 137 repr., v.q. pendant, Boreel est. £2500–3500; London, Sotheby’s, J.375.1334 Lady FALKENER [?Lady Fawkener, née 17.VII.2002, Lot 115 repr., est. £1500–2000) Harriet Churchill (1725–1777)], crayons, Φδ Society of Artists 1773, no. 124 J.375.1335 Rev. John FALKINER (c.1747–1821), rector of Carlow, pstl 23x20 ov. (Duke of Leinster, Carton, cat. 1885, p. 35, no. 25).. Lit.: Strickland 1912, n.r. J.375.135 Lord Edward FITZGERALD (1763–1798), J.375.1337 [?Robert Maxwell], Earl of FARNHAM pstl, 23x20 ov. (Duke of Leinster, Carton, cat. [(p.1720–1779)], pstl, 22x18 ov., inscr. verso 1885, p. 34 no. 6) “The Earl of Farnham last Earl married M’elle J.375.1351 Lord Gerald FITZGERALD (1766–1788), de Cantillon” (desc. family; Washington, West. pstl 23x20 ov. (Duke of Leinster, Carton, cat. Sussex, Toovey’s, 10–12.IX.2014, Lot 2 repr., 1885, p. -

Boys Will Be Boys Mt. Kili Madness

Old Stoic Society Committee President: Sir Richard Branson (Cobham/Lyttelton 68) Vice President: THE MAGAZINE FOR OLD STOICS Dr Anthony Wallersteiner (Headmaster) Chairman: Simon Shneerson (Temple 72) Issue 5 Vice Chairman: Jonathon Hall (Bruce 79) Director: Anna Semler (Nugent 05) Members: John Arkwright (Cobham 69) Peter Comber (Grenville 70) Jamie Douglas-Hamilton (Bruce 00) breaks Colin Dudgeon (Hon. Member) two world records. Hannah Durden (Nugent 01) John Fingleton (Chatham 66) Ivo Forde (Walpole 67) Tim Hart (Chandos 92) MT. KILI MADNESS Katie Lamb (Lyttelton 06) Cricket in the crater of Mount Kilimanjaro. Nigel Milne (Chandos 68) Jules Walker (Lyttelton 82) BOYS WILL BE BOYS ’Planes buzzing Stowe. Old Stoic Society Stowe School Stowe Buckingham MK18 5EH United Kingdom Telephone: +44 (0) 1280 818349 Email: [email protected] www.oldstoic.co.uk www.facebook.com/OldStoicSociety ISSN 2052-5494 Design and production: MCC Design, mccdesign.com AR END 2015 EVENTS CAL We have endeavoured to organise a wide range of events in 2015 that will appeal to Old Stoics of all ages. To make enquiries or to book any of the events below please call the Old Stoic Office on01280 818349 or email [email protected] Full details of each event can be found at www.oldstoic.co.uk To see more photos visit the OS Event Gallery at www.oldstoic.co.uk Tuesday, 17 March 2015 Monday, 6 July 2015 Old Stoics in Hong Kong Drinks Reception, Classic Car Track Day, £350 The Hong Kong Club, Hong Kong Goodwood, West Sussex, PO18 0PH Saturday, 21 March 2015 Sunday, 12 -

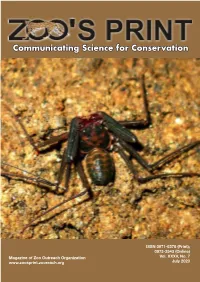

Communicating Science for Conservation

Communicating Science for Conservation ISSN 0971-6378 (Print); 0973-2543 (Online) Magazine of Zoo Outreach Organization Vol. XXXV, No. 7 www.zoosprint.zooreach.org July 2020 Communicating science for conservation Vol. XXXV, No. 7, July 2020 ISSN 0971-6378 (Print); 0973-2543 (Online) Contents Bugs R All Phrynus whitei (Gervais, 1842) from the type locality Burdwan is actually Charinus bengalensis (Gravely, 1911) -- Ayan Mondal, Debomay Chanda, Swapnanil Patra & Manabendu Barman, Pp. 1–3 Mammal Tales New range extension by Asian Elephant Elephas maximus L. - a case study of Oddanchatram Forest Range in Dindigul Forest Division, Tamil Nadu, southern India -- G. Sivasubramanian & B. Ramakrishnan, Pp. 4–12 Co-exist or Collapse? Defining the “new normal” existence -- Arya Sidharthan, Pp. 13–14 Corrigenda, Pp. 15–17 Ex situ The evolving role of Indian zoos as “Centers for Education” with special reference to National Zoological Park, New Delhi -- Natasha S Vashisth, Saurabh Vashisth, Ramesh Kumar Pandey & Suneesh Buxy, Pp. 18–23 Reports Celebration of Earth day and World Turtle day through social media -- Akhilesh Kumar & Sonika Kushwaha, Pp. 24–25 Alpine Musk Deer Moschus chrysogaster conservation outreach program in Khaptad National Park, Nepal -- Tilak Thapamagar, Shivish Bhandari, Kishor Chandra Ghimire & Daya Ram Bhusal, Pp. 26–27 Cover photo by Ayan Mondal. ISSN 2230-7052 ISSN 2230-7052 #187 21 July 2020 No. 23, Feb 2017 No. 23, Feb 2017 XX XXXXXXX XXXX xxxxxxx 21 February 2017 XX XXXXXXX XXXX xxxxxxx 21 February 2017 Newsletter of the Newsletter of the Invertebrate Conservation & Information Network of South Asia (ICINSA) Invertebrate Conservation & Information Network of South Asia (ICINSA) Phrynus whitei (Gervais, 1842) from the type locality Burdwan is actually Charinus bengalensis (Gravely, 1911) Charinus bengalensis sighted in Ramnabagan WS, Burdwan, West Bengal, India (© Ayan Mondal). -

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH

NUMBER 32 2010 GAJAHJournal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group Number 32 (2010) The journal is intended as a medium of communication on issues that concern the management and conservation of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) both in the wild and in captivity. It is a means by which members of the AsESG and others can communicate their experiences, ideas and perceptions freely, so that the conservation of Asian elephants can benefit. All articles published in Gajah reflect the individual views of the authors and not necessarily that of the editorial board or the AsESG. Editor Jayantha Jayewardene Biodiversity and Elephant Conservation Trust 615/32 Rajagiriya Gardens Nawala Road, Rajagiriya Sri Lanka [email protected] Editorial Board Dr. Richard Barnes Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando Ecology, Behavior & Evolution Section Centre for Conservation and Research Division of Biological Sciences MC-0116 35 Gunasekara Gardens University of California at San Diego Nawala Road La Jolla, CA 92093-0116 Rajagiriya USA Sri Lanka e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr. Jennifer Pastorini Heidi Riddle Centre for Conservation and Research Riddles Elephant & Wildlife Sanctuary 35 Gunasekara Gardens P.O.Box 715 Nawala Road, Rajagiriya Greenbrier, Arkansas 72058 Sri Lanka USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr. Alex Rübel Arnold Sitompul Direktor Zoo Zürich Conservation Science Initiative Zürichbergstrasse 221 Jl. Setia Budi Pasar 2 CH - 8044 Zürich Komp. Insan Cita Griya Blok CC No 5 Switzerland Medan, 20131 e-mail: [email protected] Indonesia e-mail:[email protected] GAJAH Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH Number 32 (2010) The journal is intended as a medium of communication on issues that concern the management and conservation of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) both in the wild and in captivity. -

'A Most Active, Enterprising Officer': Captain John Perkins, the Royal

'A most active, enterprising officer': Captain John Perkins, the Royal Navy and the boundaries of slavery and liberty in the Caribbean HAMILTON, Douglas <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1754-2386> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/15527/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version HAMILTON, Douglas (2017). 'A most active, enterprising officer': Captain John Perkins, the Royal Navy and the boundaries of slavery and liberty in the Caribbean. Slavery and Abolition, 39 (1), 80-100. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk 1 ‘A most active, enterprising officer’: Captain John Perkins, the Royal Navy and the boundaries of slavery and liberty in the Caribbean Douglas Hamilton Ascription: Douglas Hamilton is Head of History at Sheffield Hallam University, Owen Building, City Campus, Sheffield, S1 1WB, UK. Email: [email protected] Acknowledgements: I am grateful to the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK for the award of the 2014-15 Caird Senior Fellowship, which supported this research. Abstract: John Perkins was the most senior black officer in the Royal Navy during the American War of Independence and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He rose through the ranks from a carpenter's enslaved servant in 1759 to post captain in 1800, and went on to be one of the very first British officials to land in newly-independent Haiti in 1804. -

Hugh Douglas HAMILTON III Named Sitters

Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800 Online edition HAMILTON, Hugh Douglas & Glin 1997, fig. 6, both unidentified; Dublin 1740–1808 Ingamells 1997, p. 451 ϕ Part III: Named sitters M–Z J.375.1691 Sir Horatio MANN (1744–1814) with his hound, pstl/ppr, 111.8x91.4, c.1785 (Lord Cornwallis, dep.: Marylebone Cricket Club, London) Φ J.375.17 Joseph Bourke, 3rd Earl of MAYO (c.1740– 1794), pstl (Countess of Mayo 1904). Exh.: ~grav. Collyer, for British album, 1789 London 1904, no. 463 n.r. J.375.1708 William MILBANK (1768–1802) of J.375.1701 Sir Peniston Lamb, Viscount Thorpe Perrow, against the Temple of MELBOURNE (1745–1828), in a mauve coat; & Vespasian, Rome, black chlk, pstl/ppr, 95x67, pendant: J.375.1702 lady, in blue dress, with c.1790 (Dublin, NGI, inv. 7731. London, white veil over her head, pstl, ov. (Cowper Christie’s, 14.XI.1972, Lot 66 n.r., 450 gns; Photo courtesy owner collection; desc.: Lady Desborough, Martyn Gregory, London, 1977). Exh.: Manners, v. Tyrconnel Panshanger; London, Christie’s, 16.X.1953, Lot London 1977, no. 19 repr.; Hamilton 2008, no. J.375.1695 Richard MARLAY (1726–1802), DD, 7 n.r., £20; Lock) 41 repr. Lit.: Le Harivel 1983, repr.; Figgis dean of Ferns, later bishop of Waterford, pstl, J.375.1703 Lady MENZIES [?née Lady Mary Stuart ( 1988, p. 131 repr.; Crookshank & Glin 1997, 23x20 ov. (Duke of Leinster, Carton, cat. 1885, –1773)], in blue and white dress, with black fig. 3; Bourke & Bhreathnach-Lynch 1999, p. p. 35, no.