The Bank of England: a Socio-Economic Inquiry Into Private Money Creation, Public Debt Financing and the Long Run Implications for Inequality in Britain and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

Staff Working Paper No. 845 Eight Centuries of Global Real Interest Rates, R-G, and the ‘Suprasecular’ Decline, 1311–2018 Paul Schmelzing

CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 -

The Bank Restriction Act and the Regime Shift to Paper Money, 1797-1821

European Historical Economics Society EHES WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY | NO. 100 Danger to the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street? The Bank Restriction Act and the regime shift to paper money, 1797-1821 Patrick K. O’Brien Department of Economic History, London School of Economics Nuno Palma Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute Department of Economics, Econometrics, and Finance, University of Groningen JULY 2016 EHES Working Paper | No. 100 | July 2016 Danger to the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street? The Bank Restriction Act and the regime shift to paper money, 1797-1821* Patrick K. O’Brien Department of Economic History, London School of Economics Nuno Palma Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute Department of Economics, Econometrics, and Finance, University of Groningen Abstract The Bank Restriction Act of 1797 suspended the convertibility of the Bank of England's notes into gold. The current historical consensus is that the suspension was a result of the state's need to finance the war, France’s remonetization, a loss of confidence in the English country banks, and a run on the Bank of England’s reserves following a landing of French troops in Wales. We argue that while these factors help us understand the timing of the Restriction period, they cannot explain its success. We deploy new long-term data which leads us to a complementary explanation: the policy succeeded thanks to the reputation of the Bank of England, achieved through a century of prudential collaboration between the Bank and the Treasury. JEL classification: N13, N23, N43 Keywords: Bank of England, financial revolution, fiat money, money supply, monetary policy commitment, reputation, and time-consistency, regime shift, financial sector growth * We are grateful to Mark Dincecco, Rui Esteves, Alex Green, Marjolein 't Hart, Phillip Hoffman, Alejandra Irigoin, Richard Kleer, Kevin O’Rourke, Jaime Reis, Rebecca Simson, Albrecht Ritschl, Joan R. -

Descendants of John Pelly

Descendants of John Pelly Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of John Pelly 1-John Pelly was born on 9 Jun 1711 and died on 22 Nov 1762 at age 51. John married Elizabeth Hinde, daughter of Henry Hinde. Elizabeth was born in 1717 and died on 6 Nov 1761 at age 44. They had two children: Henry Hinde and John. 2-Capt. Henry Hinde Pelly was born on 6 Jun 1744 in West Ham, London and died on 23 Feb 1818 at age 73. Henry married Sally Hitchen Blake,1 daughter of Capt. John Blake, on 13 Jul 1776. Sally was born in 1744 and died on 15 May 1824 at age 80. They had four children: John Henry, William, Charles, and Francis. 3-Sir John Henry Pelly 1st Bt. was born on 31 Mar 1777 in West Ham, London and died on 13 Aug 1852 in Upton Manor, Plaistow, Essex at age 75. General Notes: Sir John Henry Pelly, 1st Bt. was a Younger Brother of Trinity House in 1803. He was Deputy Governor of the Hudson Bay Company between 1812 and 1822. He was Captain of the Honourable East India Company Service. He was a Member of Court Bank of England between 1822 and 1852. He was Governor of the Hudson Bay Company between 1822 and 1852. He held the office of Elder Brother of Trinity House in 1823. He was Deputy Master of Trinity Master in 1834. He was created 1st Baronet Pelly, of Upton, Essex [U.K.] on 12 August 1840. Noted events in his life were: • He worked as a Director of the Bank of England in Threadneedle Street, London. -

Inner Temple Library Newsletter Issue 43 – January 2016

Contents Saturday Opening Legal Research Training 1 One of the four Inn Libraries is open from 10.00 a.m. Saturday Opening 1 to 5.00 p.m. on each Saturday during the legal terms. Westlaw Commentary Trial 1 Annual Review 2015 2 January IT Changes 8 30 January Inner Temple Library Committee 8 Digital Images: Inns of Court 8 February AccessToLaw: Banking 9 6 February Lincoln’s Inn New Acquisitions 10 13 February Middle Temple Book Prize 11 20 February Gray’s Inn David Humphreys, 1922-2015 11 27 February Inner Temple March 5 March Lincoln’s Inn 12 March Middle Temple Legal Research Training 19 March Gray’s Inn 26 March CLOSED Dates for our next series of training sessions for new April pupils are as follows:- 2 April Inner Temple Session 1: Essentials of Legal Research To view a Saturday Opening Timetable click here. Monday 4 April 2016, 6.00 p.m. to 7.30 p.m. Location: Inner Temple Drawing Room Session 2: Legal Research Workshop: Cases Westlaw Commentary Trial Tuesday 12 April 2016, 6.00 p.m. to 7.00 p.m. Location: Inner Temple Committee Room We have been given access to Westlaw commentary sources for a three-month trial period starting on Session 3: Legal Research Workshop: Legislation 1 February. The trial includes works such as Archbold, Tuesday 19 April 2016, 6.00 p.m. to 7.00 p.m. Charlesworth & Percy, Chitty, Clerk & Lindsell, Kemp Location: Inner Temple Committee Room & Kemp, McGregor, The White Book and Woodfall. For more details click here. -

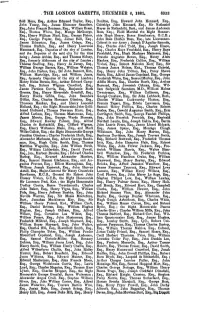

The London Gazette, December 6, 1881

. THE LONDON GAZETTE, DECEMBER 6, 1881. 6553 'field Hora, Esq., Arthur Edmund Taylor, Esq., Doulton, Esq., Howard John Kennard, Esq., John Young, Esq., James Ebenezer Saunders, Coleridge John Kennard, Esq., Sir .Nathaniel Esq., John Francis Bontems, Esq., William Brass, Meyer de Rothschild, Bart, and James Anderson Esq., Thomas "White, Esq., Mungo McGeorge, Rose, Esq.; Field Marshal the Right Honour- Esq., Henry William Nind, Esq., George Fisher, able Hugh Henry, Baron Strathnairn, G.C.B. j Esq., George Pepler, Esq., James Bell, Esq., John Rose Holden Rose, Esq., late Lieutenant- James Edmeston, Esq., James Crispe, Esq., Colonel in our Army ; Joseph D'Aguilar Samuda, Thomas Rudkin, Esq., and Henry Lawrence Esq., Charles John Todd, Esq., Joseph Hoare, Hammack, Esq.. Deputies of the city of London, Esq., Charles Kaye Freshfield, Esq., Henry Raye and the Deputies of the said city for the time Freshfield, Esq., Hugh Mackaye Matheson, Esq., being ; James Abbiss, Esq., and Thomas Sidney, Francis Augustus Bevan, Esq., Henry Alers Esq., formerly Aldermen of the city of London ; Hankey, Esq., Frederick Collier, Esq., William Thomas Snelling, Esq., Henry de Jersey, Esq., Vivian, Esq., Robert Malcolm Kerr, Esq., Sir William George Barnes, Esq., William Webster, Thomas James Nelson, Knt., Thomas Gabriel, Esq., John Parker, Esq., Sir John Bennett, Knt., Esq., Henry John Tritton, Esq., Percy Shawe William Hartridge, Esq., and William Jones, Smith, Esq., Alfred James Copeland, Esq., George Esq., formerly Deputies of the city of London; Frederick White, Esq., Samuel Morley, Esq., John Henry Hulse Berens, Esq., Arthur Edward Camp- Alldin Moore, Esq., Charles Booth, Esq., Arthur bell, Esq., Robert Wigram Crawford, Esq., Burnand, Esq., Jeremiah Colman, Esq., Wil- James Pattison Currie, Esq., Benjamin Buck liam Sedgwick Saunders, M.D., William Holme Greene, Esq., Henry Riversdale Grenfell, Esq., Twentyman, Esq., William Collinson, Esq., Henry Hucks Gibbs, Esq., John Saunders George Croshaw, Esq., Sir John Lubbock. -

A General History of the Burr Family, 1902

historyAoftheBurrfamily general Todd BurrCharles A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE BURR FAMILY WITH A GENEALOGICAL RECORD FROM 1193 TO 1902 BY CHARLES BURR TODD AUTHOB OF "LIFE AND LETTERS OF JOBL BARLOW," " STORY OF THB CITY OF NEW YORK," "STORY OF WASHINGTON,'' ETC. "tyc mis deserves to be remembered by posterity, vebo treasures up and preserves tbe bistort of bis ancestors."— Edmund Burkb. FOURTH EDITION PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY <f(jt Jtnuhtrboclur $«88 NEW YORK 1902 COPYRIGHT, 1878 BY CHARLES BURR TODD COPYRIGHT, 190a »Y CHARLES BURR TODD JUN 19 1941 89. / - CONTENTS Preface . ...... Preface to the Fourth Edition The Name . ...... Introduction ...... The Burres of England ..... The Author's Researches in England . PART I HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL Jehue Burr ....... Jehue Burr, Jr. ...... Major John Burr ...... Judge Peter Burr ...... Col. John Burr ...... Col. Andrew Burr ...... Rev. Aaron Burr ...... Thaddeus Burr ...... Col. Aaron Burr ...... Theodosia Burr Alston ..... PART II GENEALOGY Fairfield Branch . ..... The Gould Family ...... Hartford Branch ...... Dorchester Branch ..... New Jersey Branch ..... Appendices ....... Index ........ iii PART I. HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL PREFACE. HERE are people in our time who treat the inquiries of the genealogist with indifference, and even with contempt. His researches seem to them a waste of time and energy. Interest in ancestors, love of family and kindred, those subtle questions of race, origin, even of life itself, which they involve, are quite beyond their com prehension. They live only in the present, care nothing for the past and little for the future; for " he who cares not whence he cometh, cares not whither he goeth." When such persons are approached with questions of ancestry, they retire to their stronghold of apathy; and the querist learns, without diffi culty, that whether their ancestors were vile or illustrious, virtuous or vicious, or whether, indeed, they ever had any, is to them a matter of supreme indifference. -

Whitehall, April^8-, 1842;

Hicks, Walter Anderson Peacock, Robert West- Venables, Josia.h, Wilson, Alfred Wils.cm, . wood, Thomas Quested Finqis, James, Ranishaw, Lea Wilson, Edward Lawford, Peter Laurie, Edward William Stevens, John Atkinson, James Southby Wilson, Richard Lea Wilson, Robert Ellis, William Bridge, John Brown, Edward Godson, Thomas Peters, James Walkinshaw, Joseph Somes, jun., Pewtress, Joshua Thomas Bedford, Henry John Samuel Gregson, William Hughes Hughes, jun., Eltnes, John William tipss, William Muddel), Henry Alexander Rogers, George Magnay, John Master- Prichard, Benjamin Stubbing, Henry Smith, man, jun., Daniel Mildred, Frederick Mildred, John. • Thomas Watkins, and George Wright, Esqi's., Meek Britten, Richard Lambert Jones, David Wij- Deputies of • the city of London, and the liams Wire, Charles Pearson, Thomas Saunder?, and. Deputies thereof for the time being ; John Garratt, James Cosmo Melville, Esqrs. Edward Tickner, Robert Williams, James Brogden, and Stephen Edward Thornton, Esqis., Sir Thomas Neave, Bart., Jeremiah Olive, Jeremiah Harman, ' Isaac Solly, Andrew Loughnan, Abel Chapman, Whitehall, April 25, 1842. Cornelius Buller, Wilj'mm Ward, and Melvil Wilson, . Esqrs,, Sir John Henry Felly, Bart., William Cotton, .The Queen has been graciously pleased, 'np'-n Robert Barclay, Edward Henry Chapman, Henry the nomination of his Grace the Duke of NorioJk, Davidson, Charles Pasr.oe Grenfell, Abel Lewes Earl Marshaland Hereditary Marshal of England,. Gower, Thomson Hankey, junr., John Oliver to appoint Edward Howard Gibbon, Esq. Moworay. Hanson, John Benjamin Heath, Kirkman Daniel Herald of Arms Extraordinary. • Hodgson, Charles Frederick Hiith, Alfred Latham, James Malcolmson, • Jauies Morris, Sheffield .Neave, George Warde. Norman, John .Horsley Palmer, James Pattison, • Christopher Pearse, Henry James Foreign-Office, May, 2, 1842: , Prescdtt, and Charles Pole, Esqrs., Sir John Rae Read, Bart., William R. -

January 2013 Abdul Bangura, Howard University, John Birchall

THE JOURNAL OF SIERRA LEONE STUDIES – Volume 2 – Edition 1 – January 2013 Editorial Panel Abdul Bangura, Howard University, John Birchall, Ade Daramy, David Francis, University of Bradford, Lansana Gberie, Dave Harris, School of Oriental and African Studies University of London, Philip Misevich, St John’s University, New York, John Trotman. Dedication I recently made contact with Professor John Hargreaves, who some of you will know was the last Editor of this Journal. He was delighted to hear of its re-appearance and so we have dedicated this edition to John and thank him for his scholarship and dedication to the academic life of Sierra Leone. In this edition Monetary Policy and the Balance of Payments: Econometric Evidence from Sierra Leone - Samuel Braima, Head of Economics Department, Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone and Robert Dauda Korsu, Senior Economist, West African Monetry Agency. Addressing Organised Crime in Sierra Leone: The Role of the Security-Development Nexus - Sacha Jesperson, London School of Economics and Political Science. Book Review A Critique of Epistemologies of African Conflicts: Violence, Evolutionism and the War in Sierra Leone (New York: Palgrave, 2012) - Lans Gberie A new section We are pleased to introduce an end section that focuses on issues that will be of interest to those currently studying Sierra Leone and those who will follow this generation. In this edition we have: The naming of Sierra Leone - Peter Andersen Edward Hyde, Murray Town - pilot in The Battle of Britain. The chase for Bai Bureh - The London Gazette, 29th December, 1899. Peer Reviewed Section In this edition we have included a range of different articles. -

Cornell Law School

CORNELL LAW SCHOOL Central Bank Money: Liability, Asset, or Equity of the Nation? Michael Kumhof(1), Jason Allen(2), Will Bateman(3), (4) (5) (6) Rosa Lastra , Simon Gleeson , Saule Omarova (1) CEPR and Centre for Macroeconomics. Email: [email protected] (2) Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. Email: jason.allen@hu‐berlin.de (3) Australian National University. Email: [email protected] (4) Queen Mary University of London. Email: [email protected] (5) Clifford Chance. Email: [email protected] (6) Cornell University. Email: [email protected] Cornell Law School research paper No. 20-46 Cornell Law School Myron Taylor Hall Ithaca, NY 14853-4901 This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract=3730608 Draft 5 August 2020 Central Bank Money: Liability, Asset, or Equity of the Nation? Michael Kumhof(1), Jason Allen (2) Will Bateman (3), Rosa Lastra (4), Simon Gleeson (5), Saule Omarova (6) Abstract Based on legal arguments, we advocate a conceptual and normative shift in our understanding of the economic character of central bank money (CBM). The widespread treatment of CBM as a central bank liability goes back to the gold standard, and uses analogies with commercial bank balance sheets. However, CBM is sui generis and legally not comparable to commercial bank money. Furthermore, in modern economies, CBM holders cannot demand repayment of CBM in anything other than CBM. CBM is not an asset of central banks either, and it is not central bank shareholder equity because it does not confer the same ownership rights as regular shareholder equity. -

Explanatory Notes

BANK OF ENGLAND AND FINANCIAL SERVICES BILL [HL] EXPLANATORY NOTES What these notes do These Explanatory Notes relate to the Bank of England and Financial Services Bill [HL] as brought from the House of Lords on 19 January 2016 (Bill 120). • These Explanatory Notes have been prepared by the Treasury in order to assist the reader of the Bill and to help inform debate on it. They do not form part of the Bill and have not been endorsed by Parliament. • These Explanatory Notes explain what each part of the Bill will mean in practice; provide background information on the development of policy; and provide additional information on how the Bill will affect existing legislation in this area. • These Explanatory Notes might best be read alongside the Bill. They are not, and are not intended to be, a comprehensive description of the Bill. So where a provision of the Bill does not seem to require any explanation or comment, the Notes simply say in relation to it that the provision is self‐explanatory. Bill 120–EN 56/1 Table of Contents Subject Page of these Notes Overview of the Bill 3 Policy background 4 Legal background 6 Territorial extent and application 7 Commentary on provisions of Bill 9 Part 1: The Bank of England 9 Clause 1: Membership of court of directors 9 Clause 2: Term of office of non‐executive directors 9 Clause 3: Abolition of Oversight Committee 9 Clause 4: Functions of non‐executive directors 9 Clause 5: Financial stability strategy 9 Clause 6: Financial Policy Committee: status and membership 10 Clause 7: Monetary Policy Committee: -

British Banks' Role in U.K. Capital Markets Since the Big Bang

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 68 Issue 1 Chicago-Kent Dedication Symposium Article 27 December 1992 British Banks' Role in U.K. Capital Markets since the Big Bang Philip N. Hablutzel IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Philip N. Hablutzel, British Banks' Role in U.K. Capital Markets since the Big Bang, 68 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 365 (1992). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol68/iss1/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BRITISH BANKS' ROLE IN U.K. CAPITAL MARKETS SINCE THE BIG BANG PHILIP N. HABLUTZEL* In the Fall of 1986, two legal events occurred in the United King- dom which became known as the "Big Bang." First, on October 27, the actual "Big Bang" was a reform in the operation of the Stock Exchange in the form of a settlement between the Exchange and the Government regarding claims that the Exchange had been anticompetitive. Particular practices complained of were the fixed brokerage commissions and the separation of brokers (who could not act on their own account) and job- bers (market-makers could not act for customers). The Big Bang abol- ished fixed commissions and the distinction between brokers and jobbers.1 Then, on November 7, 1986, the Financial Services Act began com- ing into force, a process completed by April 29, 1988.