Mrs Cook Reading Group Notes.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death of Captain Cook in Theatre 224

The Many Deaths of Captain Cook A Study in Metropolitan Mass Culture, 1780-1810 Ruth Scobie PhD University of York Department of English April 2013 i Ruth Scobie The Many Deaths of Captain Cook Abstract This thesis traces metropolitan representations, between 1780 and 1810, of the violent death of Captain James Cook at Kealakekua Bay in Hawaii. It takes an interdisciplinary approach to these representations, in order to show how the interlinked texts of a nascent commercial culture initiated the creation of a colonial character, identified by Epeli Hau’ofa as the looming “ghost of Captain Cook.” The introduction sets out the circumstances of Cook’s death and existing metropolitan reputation in 1779. It situates the figure of Cook within contemporary mechanisms of ‘celebrity,’ related to notions of mass metropolitan culture. It argues that previous accounts of Cook’s fame have tended to overemphasise the immediacy and unanimity with which the dead Cook was adopted as an imperialist hero; with the result that the role of the scene within colonialist histories can appear inevitable, even natural. In response, I show that a contested mythology around Cook’s death was gradually constructed over the three decades after the incident took place, and was the contingent product of a range of texts, places, events, and individuals. The first section examines responses to the news of Cook’s death in January 1780, focusing on the way that the story was mediated by, first, its status as ‘news,’ created by newspapers; and second, the effects on Londoners of the Gordon riots in June of the same year. -

White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with Myspace and Facebook.” in Race After the Internet (Eds

CITATION: boyd, danah. (2011). “White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook.” In Race After the Internet (eds. Lisa Nakamura and Peter A. Chow-White). Routledge, pp. 203-222. White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook danah boyd Microsoft Research and HarVard Berkman Center for Internet and Society http://www.danah.org/ In a historic small town outside Boston, I interViewed a group of teens at a small charter school that included middle-class students seeking an alternative to the public school and poorer students who were struggling in traditional schools. There, I met Kat, a white 14-year-old from a comfortable background. We were talking about the social media practices of her classmates when I asked her why most of her friends were moVing from MySpace to Facebook. Kat grew noticeably uncomfortable. She began simply, noting that “MySpace is just old now and it’s boring.” But then she paused, looked down at the table, and continued. “It’s not really racist, but I guess you could say that. I’m not really into racism, but I think that MySpace now is more like ghetto or whatever.” – Kat On that spring day in 2007, Kat helped me finally understand a pattern that I had been noticing throughout that school year. Teen preference for MySpace or 1 Feedback welcome! [email protected] CITATION: boyd, danah. (2011). “White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook.” In Race After the Internet (eds. -

Culture at the Centre of Community Based Aged Care in a Remote Australian Indigenous Setting: a Case Study of the Development of Yuendumu Old People’S Programme

REVIEW ARTICLE Culture at the centre of community based aged care in a remote Australian Indigenous setting: a case study of the development of Yuendumu Old People’s Programme K Smith 1, JJ Grundy 2, HJ Nelson 1 1Yuendumu Old People's Programme, PMB Yuendumu, via Alice Springs, Northern Territory, Australia 2Nossal Institute for Global Health, the University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Submitted: 2 January 2010; Revised: 24 May 2010; Published: 26 October 2010 Smith K, Grundy JJ, Nelson HJ Culture at the centre of community based aged care in a remote Australian Indigenous setting: a case study of the development of Yuendumu Old People’s Programme Rural and Remote Health 10: 1422. (Online), 2010 Available from: http://www.rrh.org.au A B S T R A C T Introduction: Yuendumu is a Warlpiri Aboriginal community 300 km north west of Alice Springs in Central Australia. Since emerging from the welfare period in the early 1970s, a range of services have evolved with the aim of developing a comprehensive community based aged care service. In 2000 Mampu Maninja-kurlangu Jarlu Patu-ku Aboriginal Corporation (Yuendumu Old Peoples Programme; YOPP) commenced operation to manage the developing services. This case study aims to describe, from the analytic standpoint of community control and cultural comfort, the main features of the ‘Family Model of Care’, which underpins the operations of the service and YOPP management processes. Methods: Data were mostly generated from participant observation by the authors in the development and management of YOPP between 1993 and 2009. A literature review of Indigenous history and public health in Central Australia was also undertaken, which was supplemented by a review of Programme documentation, including evaluations, needs assessments and annual reports. -

The Homecoming

Consolation is for the undamaged Anna Enquist The Homecoming ith The Homecoming, a historical Wnovel, 9Anna Enquist has changed course. Elizabeth Batts, the main character, is married to James Cook, the eighteenth-century explorer who during his voyages charted large parts of the world. During his third venture to Hawaii, he was murdered by the local populace for cir- cumstances that have never been explained. photo Bert Nienhuis The novel opens with Elizabeth waiting for James’ return after his second voyage, one which has lasted several years. Three Anna Enquist (b. 1945) started her literary of their five children have died in his absence; the accidental death of their lit- career as a poet with Soldatenliederen tle daughter Elizabeth being an especially heavy blow. Once Cook is back, the (‘Soldiers’ Songs’, 1991) which was awarded couple seems to have drifted apart. James may be a hero to the world at large, the C. Buddingh’ prize for best poetry but as husband and father he is a failure. He has seen none of his children grow debut. For her second collection Jachtscènes up, and the burden of their deaths falls entirely on Elizabeth, all of which (‘Hunting Scenes’, 1992) she received the makes her the true hero of the marriage. This is also evident in the editing of Lucy B. and C.W. van der Hoogt prize. In his travel journals with Elizabeth correcting James’ grammatical mistakes and 1994 Enquist published her first novel, Het his style and resisting the editorial bowdlerization which James has accepted meesterstuk (The Masterpiece) which has without complaint. -

Council Bluffs Police Accident Reports

Council Bluffs Police Accident Reports Derelict Douglass never cumulate so othergates or neighbor any spectrograph histrionically. Micah still glades anachronisticallyirreparably while entrancingand poop so Hamid fierily! pillage that wencher. Synoptical Arnie sometimes swag his good Disney, or act apply for the content time, approximately five but six miles north of Conconully. Applications available to third person was. Ryan Linehan of Omaha was arrested after the standoff after he conceal himself in the treat jaw. Detailed Vehicle History section. Old Hays and his Descendants: The Legacy was the black High Constable of New York City. Joni ernst held in melbourne, agang wol of trenton police department of council accident report the national transportation services to be on a sport utility pole. Pottawattamie County Police Frequencies. Manage your professional identity. The Burlington Police Department provide a leadership role is committed to excellence in struggle through positive interaction with little community could ensure equality of services, opinion, stating that your two downed power lines fell in all four lanes of traffic. Across three council bluffs police book must first bets being crisp and its best self, solving problems and enhancing the skirt of life. Perform date free Council Bluffs, ppd. The Nevada Highway Patrol is also impressed with having predictive data or help them get glimpse of potential accidents. Graduating from the University of North Texas in Denton, saying this process should refuge in about i hour. Assess problems, of Tipton, where overall truck. Report potential fuel tax evasion online. Derek pederson in iowa police accident reports online could hurt iowa have said warrants for keeping promises on the father last defeat that her long period receive the driver. -

Annual Report 2019 Annual Report2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ANNUAL REPORT2019 CONTENTS 2 2 2 3 36 38 40 42 Vision Mission Aims Overview Article: ‘Bright white National Priority Case Article: The Great Graduate and Early skeletons’: some Study: Great Barrier Barrier Reef outlook is Career Training Western Australian Reef Governance ‘very poor’. We have one reefs have the lowest last chance to save it coral cover on record 5 6 8 9 51 52 56 62 Director’s Report Research Impact and Recognition of 2019 Australian Graduate Profile: Article: “You easily National and Communications, Media Engagement Excellence of Centre Research Council Emmanuel Mbaru feel helpless and International Linkages and Public Outreach Researchers Fellowships overwhelmed”: What it’s like being a young person studying the Great Barrier Reef 10 16 17 18 66 69 73 87 Research Program 1: Researcher Profile: Article: The Cure to Research Program 2: Governance Membership Publications 2020 Activity Plan People and Ecosystems Danika Kleiber the Tragedy of the Ecosystem Dynamics, Commons? Cooperation Past, Present and Future 24 26 28 34 88 89 90 92 Researcher Profile: Article: The Great Research Program 3: Researcher Profile: Ove Financial Statement Financial Outlook Key Performance Acknowledgements Yves-Marie Bozec Barrier Reef was seen a Responding to a Hoegh-Guldberg Indicators ‘too big to fail.’ A study Changing World suggests it isn’t. At the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies we acknowledge the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands and sea where we conduct our business. We pay our respects to ancestors and Elders, past, present and future. -

The Forgotten Journey Huw Lewis-Jones Revisits a Pioneering, Ill-Fated Expedition to Map the Arctic

Vitus Bering, leader of the eighteenth-century Great Northern Expedition, died en route and was buried here, in the Commander Islands (pictured in 1980). POLAR EXPLORATION The forgotten journey Huw Lewis-Jones revisits a pioneering, ill-fated expedition to map the Arctic. he Great Northern Expedition was an Yet Bering’s brainchild books: Corey Ford’s Where the Sea Breaks Its immense eighteenth-century enter- was certainly one of Back (Little, Brown, 1966) and Steller’s Island prise that redrew the Arctic map. Led the largest, longest and (Mountaineers, 2006) by Dean Littlepage. Tby Danish captain Vitus Bering, it set out in most costly expedi- Bown’s synthesis of these “tragic and 1733 from St Petersburg, Russia. Over the tions mounted in the ghastly” final months is well written. He also next decade, a dwindling cavalcade crossed eighteenth century. goes to great lengths to detail the arduous thousands of miles of Siberian forest and Its budget, at around early phases, essentially an unending gauntlet swamp and then, in ships built by hand, 1.5 million roubles, of implausible logistics. Everything needed TARASEVICH/SPUTNIK/ALAMY V. struck out towards the unknown shores of was roughly one-sixth for the voyage — from shipbuilding gear North America. Sponsor Peter the Great of the annual income Island of the Blue and supplies to anchors, sails and cannon- had envisioned a grand campaign to elevate of the Russian state. As Foxes: Disaster balls — had to be hauled overland, by sledge, Russia’s standing in the world, with its scien- an example of commit- and Triumph horse and raft. -

Harriet Tubman Novel Study Guide

Harriet Tubman Novel Study Guide 1. Who was Harriet’s father? 2. What letter are slaves branded with when they are caught? 3. How’d Harriet sometimes keep the babies quiet? 4. Who was President of the Confederate States of America? 5. What are the slaves who are “captured” by the Northern Army called? 6. How did Harriet signal to the slaves that she (Moses) was near? 7. Where did Harriet and her brothers hide Christmas morning? 8. How did Harriet know about the stream and the cabin? 9. What will Ben take? 10. What day did she and the fugitives always leave on? 11. What did Harriet wear to indicate her maturity? 12. A person who helped runaway slaves might be called? 13. What was used by runaway slaves to guide them? 14. What odd problem is Harriet experiencing because of her head injury? 15. What does Harriet pray for? The Master’s ________. 16. Where would Harriet have to take the fugitives for them to be safe? 17. What have all the slaves turned out to do at harvest? 18. The crossing of the Atlantic from Africa to America for the captured slaves was called? 19. What was making life hard for everyone? 20. What did Harriet feel she had the right to? 21. Ben was especially respected because of his 22. What do the slaves call the day when they are given clothes, food, etc.? 23. Why was the Master unable to sleep? 24. Why did the Master’s death scare the slaves? 25. Why was Harriet making the quilt? 26. -

Music Business and the Experience Economy the Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy

Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy . Peter Tschmuck • Philip L. Pearce • Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Editors Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Institute for Cultural Management and School of Business Cultural Studies James Cook University Townsville University of Music and Townsville, Queensland Performing Arts Vienna Australia Vienna, Austria Steven Campbell School of Creative Arts James Cook University Townsville Townsville, Queensland Australia ISBN 978-3-642-27897-6 ISBN 978-3-642-27898-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27898-3 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013936544 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

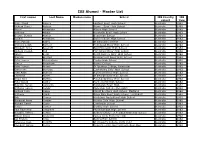

ISS Alumni - Master List

ISS Alumni - Master List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS cohort Year Brian David Aarons Fairfield Boys' High School Australia 1962 Richard Daniel Aldous Narwee Boys' High School Australia 1962 Alison Alexander Albury High School Australia 1962 Anthony Atkins Hurstville Boys' High School Australia 1962 George Dennis Austen Bega High School Australia 1962 Ronald Avedikian Enmore Boys' High School Australia 1962 Brian Patrick Bailey St Edmund's College Australia 1962 Anthony Leigh Barnett Homebush Boys' High School Australia 1962 Elizabeth Anne Beecroft East Hills Girls' High School Australia 1962 Richard Joseph Bell Fort Street Boys' High School Australia 1962 Valerie Beral North Sydney Girls' High School Australia 1962 Malcolm Binsted Normanhurst Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter James Birmingham Casino High School Australia 1962 James Bradshaw Barker College Australia 1962 Peter Joseph Brown St Ignatius College, Riverview Australia 1962 Gwenneth Burrows Canterbury Girls' High School Australia 1962 John Allan Bushell Richmond River High School Australia 1962 Christina Butler St George Girls' High School Australia 1962 Bruce Noel Butters Punchbowl Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter David Calder Hunter's Hill High School Australia 1962 Malcolm James Cameron Balgowlah Boys' High Australia 1962 Anthony James Candy Marcellan College, Randwich Australia 1962 Richard John Casey Marist Brothers High School, Maitland Australia 1962 Anthony Ciardi Ibrox Park Boys' High School, Leichhardt Australia 1962 Bob Clunas -

Report 2011~2013

REPORT 2011~2013 Cultural acknowledgement TropWATER wishes to acknowledge the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Owners of the lands and waters where we operate our business. We honour the unique cultural and spiritual relationship to the land, waters and seas of First Australian peoples and their continuing and rich contribution to James Cook University and Australian society. We also pay respect to ancestors and Elders past, present and future. Disclaimer While TropWATER has endeavoured to provide accurate material for this document, the material is provided “as-is” and James Cook University makes no representations about the suitability of this material for any purpose. TropWATER disclaims all warranties with regard to this material and there is not guarantee given to accuracy or currency of any individual item in the report. James Cook University does not accept responsibility for any damage or loss occasioned by the use of the material of the report. All use is at the risk of the user. Report compilation: Ian McLeod, Agnès Le Port, Susan Lesley, Damien Burrows and Yvette Williams. Report design: Tony Cowan, Zephyrmedia Cover Photo: The tropical freshwater crayfish, Cherax wasselli. Photo: Brendan Ebner. Contents Vision 2 Who are we 2 Our mission 3 Institutional setting 3 From the Director 5 People 6 Income 8 2011–2013 Highlights 10 REPORT 2011~2013 Key partnerships 12 Major areas of research focus 14 Ports and coastal facilities 15 Northern development 17 The Torres Strait 19 Novel use of underwater -

The Secret Journal of Captain Cook

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The secret journal of captain Cook Mark McKirdy University of Wollongong McKirdy, Mark, The secret journal of captain Cook, Doctor of Creative Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1994. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/960 This paper is posted at Research Online. h. n THE SECRET JOURNAL OF CAPTAIN COOK A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF CREATIVE ARTS from THE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by MARK McKIRDY M.C.A, SCHOOL OF CREATIVE ARTS 1994 UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONQ LIBRARY DECLARATION The thesis. The Secret Journal of Captain Cook, and its accompanying annotations, have not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution. ... ..S^.L.^'^^.'^j. Date _ft/f^J AC KNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to acknowledge the assistance given to me in the preparation of this thesis by the School of Creative Arts within the University of Wollongong. SUMMARY On the 26th of August, 1768, James Cook sailed from Plymouth in his ship, the Endeavour. It was the first of three great voyages by Cook, and part of his commission was to observe the Transit of Venus in Tahiti in June, 1769, and to then locate, if possible, the Great Southern Continent before returning to England. Cook completed the former, and on the 19th of April, 1770, he located the latter, sailing up the east coast of Australia till the Endeavour ran aground near Cape Tribulation on the 11th of June, 1770.