An Abstract of the Thesis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

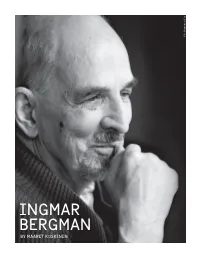

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

Child Disability: a Study of Three Families. INSTITUTION Saskatchewan Univ., Saskatoon

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 371 529 EC 303 116 AUTHOR Bloom, Barbara TITLE Child Disability: A Study of Three Families. INSTITUTION Saskatchewan Univ., Saskatoon. Dept. for the Education of Exceptional Children. PUB DATE May 93 NOTE 306p.; For a summary of the study, see EC 303 117. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Anxiety; Case Studies; *Child Rearing; *Coping; Elementary Secondary Education; Family Relationship; Foreign Countries; *Human Services; Interviews; *Mental Retardation; Observation; *Parent Attitudes; *Parent Child Relationship; Qualitative Research; Questionnaires; Stress Variables ABSTRACT This qualitative study used ouestionnaires, interviews, and observations to assess what having children with disabilities means to three families. The disabilities include severe mental retardation and seizure disorder, Down syndrome, and neurofibromatosis. Interview data were categorized into the following five areas: the children, stress/anxiety, services, pel,'.onal comments, and survival strategies. Data from MAPS (McGill Action Planning System) planning sessions with the three families are also provided. Results indicate that these families of disabled children do all the things that families ordinarily do to help their children grow and develop, but they do these things more intensely and for a longer period of time. Of particular note for these families was the intensity of the illness(es) of their children and the level and intensity of family interactions with health care professionals. Each family had many interactions, as well, with several other service delivery agencies. While many professionals provided positive, appropriate, and responsive service, each family also experienced very negative non-service from some professionals. Recommendations are offered concerning attitudes, policies, and service provision. -

28Th Leeds International Film Festival Presents Leeds Free Cinema Week Experience Cinema in New Ways for Free at Liff 28 from 7 - 13 November

LIFF28th 28 Leeds International Film Festival CONGRATULATIONS TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire in a fantastic year for filmmaking in the region INCLUDING ‘71 GET SANTA SCREENING AT LIFF28 X + Y CATCH ME DADDY & LIFF28 OPENING NIGHT FILM TESTAMENT OF YOUTH Image: (2014) Testament of Youth James Kent Dir. bfi.org.uk/FilmFund Film Fund Ad LIFF 210x260 2014-10_FINAL 3.indd 1 27/10/2014 11:06 WELCOME From its beginnings at the wonderful, century-old Hyde Park Leeds International Film Festival is a celebration of both Picture House to its status now as a major national film event, film culture and Leeds itself, with this year more than 250 CONGRATULATIONS Leeds International Film Festival has always aimed to bring screenings, events and exhibitions hosted in 16 unique a unique and outstanding selection of global film culture locations across the city. Our venues for LIFF28 include the TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL to the city for everyone to experience. This achievement main hub of Leeds Town Hall, the historic cinemas Hyde is not possible without collaborations and this year we’ve Park Picture House and Cottage Road, other city landmarks FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR assembled our largest ever line-up of partners. From our like City Varieties, The Tetley, Left Bank, and Royal Armouries, long-term major funders the European Union and the British Vue Cinemas at The Light and the Everyman Leeds, in their Film Institute to exciting new additions among our supporting recently-completed Screen 4, and Chapel FM, the new arts The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire organisations, including Game Republic, Infiniti, and Trinity centre for East Leeds. -

Philosophical Themes in the Films of Ingmar Bergman Et Al

Philosophical Themes in the Films of Ingmar Bergman et al Fall 2017 Honors 362-01 MWF 11-11:50am; DH 146 Prerequisite: acceptance into the University Honors Program, or consent of instructor. 3 credits. Also counts for 7AI, 7SI, 7VI. Instructor: Charles Webel, Ph.D. Delp-Wikinson Chair and Professor, Peace Studies. Roosevelt Hall 253. email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon/Wed/Fr 1:00-2:20pm, & by appointment Catalog Description The films of Ingmar Bergman offer a range of jumping-off points for some traditional debates in philosophy in areas such as the philosophy of religion, ethics, and value theory more broadly. Bergman’s oeuvre also offers an entry point for a critical examination of existentialism. This course will investigate some of the philosophical questions posed and positions raised in these films within an auteurist framework. We will also examine the legitimacy of the auteurist framework for film criticism and the representational capacity of film for presenting philosophical arguments. Course Learning Outcomes Upon completion of this course, students will have: a. Understood a range of philosophical positions within the tradition of Western philosophy in general and the intellectual movement called “existentialism” in particular. b. Engaged in a critical analysis of Bergman’s relationship to existentialism, based on synthesizing individual arguments and positions presented throughout his oeuvre. c. Engaged in critical analyses of various philosophical themes, traditions, and problematics, especially ethics, epistemology, philosophical psychology, and political philosophy. d. Understood arguments for and against the capacity of film to present philosophical arguments, focusing on the films of Ingmar Bergman, as well as selected films by other great directors. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Keith Sweat I Want Her Mp3, Flac, Wma

Keith Sweat I Want Her mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Funk / Soul Album: I Want Her Country: UK Released: 1987 Style: RnB/Swing, Soul, New Jack Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1469 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1718 mb WMA version RAR size: 1794 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 758 Other Formats: AU AA TTA ADX MP4 MIDI DXD Tracklist A1 I Want Her (Extended Version) 6:22 A2 I Want Her (Acappella Dub Beat) 4:07 B1 I Want Her (Instrumental) 2:42 B2 I Want Her (LP Version) 5:58 Credits Co-producer – Teddy Riley Executive-Producer – Vincent Davis Mixed By – Keith Sweat, Vincent Davis Producer – Keith Sweat Written-By – Keith Sweat, Teddy Riley Notes Published by Vintertainment Publishing Inc. / Keith Sweat Publishing / Donril Publishing Original version available on the LP "Make It Last Forever" (960673-1) Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 0 75596 67880 3 Barcode (scanned): 075596678803 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 0-66788 Keith Sweat I Want Her (12") Vintertainment, Elektra 0-66788 US 1987 7-69431 Keith Sweat I Want Her (7") Elektra, Vintertainment 7-69431 US 1987 7-69431 Keith Sweat I Want Her (7") Vintertainment, Elektra 7-69431 US 1987 I Want Her (12", ED 5265 Keith Sweat Vintertainment, Elektra ED 5265 US 1987 Promo) I Want Her (CD, 10SW8-8 Keith Sweat Elektra 10SW8-8 Japan Unknown Mini, Single) Related Music albums to I Want Her by Keith Sweat Keith Sweat - Make It Last Forever Entouch - All Nite Keith Sweat - When I Give My Love Keith Sweat - Your Love-Part 1 & 2 Keith Sweat - How Do You Like It? Keith Sweat - Why Me Baby? (Remixes) Keith Sweat - Make You Sweat Keith Sweat - I'll Give All My Love To You Keith Sweat - I'm Not Ready Keith Sweat - What Is It. -

LSG Curious Mp3, Flac, Wma

LSG Curious mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Curious Country: US Released: 1998 Style: RnB/Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1379 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1462 mb WMA version RAR size: 1725 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 323 Other Formats: AHX AC3 ASF XM FLAC MP1 MIDI Tracklist 1 Curious (No Rap Version) 3:19 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Elektra Entertainment Group Phonographic Copyright (p) – WEA International Inc. Copyright (c) – Elektra Entertainment Group Copyright (c) – WEA International Inc. Made By – WEA Manufacturing Inc. Recorded At – Southern Tracks Recorded At – Tumblin' Dice Studios Mixed At – Tumblin' Dice Studios Published By – Hip Trip Music Published By – Mid-Star Music Credits Arranged By [Vocal Arrangements] – Keith Sweat, Tumblin' Dice Inc.* Backing Vocals [Background Vocals] – Gerald Levert, Johnny Gill, Keith Sweat Co-producer – Armondo Colon*, Keith Sweat Engineer – Karl Heilbron, Paul Gregory Engineer [Mixing Engineer], Mixed By – Lou Ortiz* Executive-Producer – Gerald Levert, Keith Sweat Executive-Producer [Co-Executive Producer] – Merlin Bobb Keyboards, Programmed By – Tumblin' Dice Inc.* Producer, Arranged By – Rashad Smith Tracking By – Paul Gregory Written-By – Bo Watson, Bobby Lovelace, Melvin Gentry Notes From the EastWest Records album Levert Sweat Gill #62125 available on cassette & cd. Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: BMI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Levert Sweat EastWest UK & 7559-63841-0 Curious (12") 7559-63841-0 1998 Gill* America Europe Curious / My Body EastWest ED 6064 LSG (Remix) (12", Records ED 6064 US 1997 Promo) America Levert Sweat Levert Sweat Gill* Gill* Featuring Featuring L.L. -

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918. -

Ingmar Bergman Roland Pöntinen

INGMAR BERGMAN MUSIC FROM THE FILMS ROLAND PÖNTINEN piano BIS-2377 STENHAMMAR QUARTET | TORLEIF THEDÉEN cello Ingmar Bergman – Music From the Films 1 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.5 in C minor, BWV1011 3'47 Viskningar och rop & Saraband [Cries and Whispers & Saraband] 2 Robert Schumann: Aufschwung from Fantasiestücke, Op.12 3'17 Musik i mörker & Sommarnattens leende [Music in Darkness & Smiles of a Summer Night] 3 Frédéric Chopin: Nocturne in C sharp minor, Op.27 No.1 5'04 Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] 4 Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in D minor, Op.28 No.24 2'36 Musik i mörker 5 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.4 in E flat major, BWV1010 5'02 Höstsonaten [Autumn Sonata] 6 W.A. Mozart: Fantasy in C minor, K 475 12'26 Ansikte mot ansikte [Face to Face] 7 Frédéric Chopin: Mazurka in A minor, Op.17 No.4 3'43 Viskningar och rop 8 Franz Schubert: Andante sostenuto 9'37 Second movement of Sonata in B flat major, D 960 Larmar och gör sig till [In the Presence of a Clown] 2 9 Domenico Scarlatti: Sonata in D major, K 535 3'11 Djävulens öga [The Devil’s Eye] 10 Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in A minor, Op.28 No.2 2'17 Höstsonaten 11 Domenico Scarlatti: Sonata in E major, K 380 4'18 Djävulens öga 12 J.S. Bach: Variation 25 from Goldberg Variations, BWV988 6'39 Tystnaden [The Silence] 13 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.2 in D minor, BWV1008 5'43 Såsom i en spegel [Through a Glass Darkly] 14 Robert Schumann: In modo d’una marcia 8'44 Second movement of Piano Quintet in E flat major, Op.44 Fanny och Alexander TT: 78'28 Roland Pöntinen piano Stenhammar Quartet [Schumann: Piano Quintet] Peter Olofsson & Per Öman violins · Tony Bauer viola · Mats Olofsson cello Torleif Thedéen cello [Bach: Sarabandes] 3 Tystnaden (1963) Gunnel Lindblom and Jörgen Lindström as Anna and her son Johan © 1963 AB Svensk Filmindustri. -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. -

2015 STREET DATES FEBRUARY 10 FEBRUARY 17 Orders Due January 14 Orders Due January 21 2/10/15 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP

ISSUE 4 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH axis.wmg.com NEW RELEASE GUIDE 2015 STREET DATES FEBRUARY 10 FEBRUARY 17 Orders Due January 14 Orders Due January 21 2/10/15 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ORDERS ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP DUE The Carol Burnett Show: Together Again Burnett, Carol TSV DV 610583455298 30102-X $12.95 1/14/15 (DVD) Dr. John In The Right Place (Colored Vinyl) ACG A 603497911110 7018-A $24.98 1/14/15 Giddens, Rhiannon Tomorrow Is My Turn NON CD 075597956313 541708 $16.98 1/14/15 Mama's Family: The Complete Sixth Mama's Family TSV DV 610583464795 30372-X $29.95 1/14/15 Season (3DVD) Fire On The Bayou (Starburst Colored Meters, The RRW A 081227955939 2228 $22.98 1/14/15 Vinyl) Mike + The Mechanics Living Years (2CD) ACG CD 081227959708 542230 $24.98 1/14/15 The Black Parade (Explicit)(2LP w/D- My Chemical Romance REP A 093624933595 545468 $25.98 1/14/15 Side Etching) Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge My Chemical Romance REP A 093624933632 545465 $20.98 1/14/15 (Explicit)(Vinyl) Sweat, Keith Harlem Romance: The Love Collection ECG CD 081227955359 547638 $13.98 1/14/15 Last Update: 12/16/14 For the latest up to date info on this release visit axis.wmg.com. ARTIST: Carol Burnett TITLE: The Carol Burnett Show: Together Again (DVD) Label: TSV/Time/Life Star Vista Config & Selection #: DV 30102 X Street Date: 02/10/15 Order Due Date: 01/14/15 UPC: 610583455298 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $12.95 Alphabetize Under: B ALBUM FACTS Genre: Television Packaging Specs: Single DVD; Running Time: 158 minutes Description: MORE HILARITY WITH CAROL AND HER FUNNY CAST & GUESTS! Go ahead…try not to laugh! THE CAROL BURNETT SHOW is still zany after all these years. -

Retrospektive (PDF)

61. Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin Retrospektive Ingmar Bergman Ansikte mot ansikte (Von Angesicht zu Angesicht/Face to Face) von Ingmar Bergman mit Liv Ullmann, Erland Josephson, Aino Taube, Schweden 1975/76, schwedisch mit deutsch/französischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Cinémathèque suisse, Lausanne Ansiktet (Das Gesicht/The Magician) von Ingmar Bergman mit Max von Sydow, Ingrid Thulin, Gunnar Björnstrand, Schweden 1958, schwedisch mit englischen elektronischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm Aus dem Leben der Marionetten (Aus dem Leben der Marionetten/From the Life of the Marionettes) von Ingmar Bergman mit Christine Buchegger, Robert Atzorn, Martin Benrath, Rita Russek, BRD 1979/80, deutsch mit englischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Swedish Institute, Stockholm Beröringen / The Touch von Ingmar Bergman mit Elliott Gould, Bibi Andersson, Max von Sydow, Schweden/USA 1970/71, englisch/schwedisch mit englischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm Bilder från lekstugan (Images from the Playground) von Stig Björkman mit Ingmar Bergman, Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, Schweden 2009, schwedisch mit englischen Untertiteln, Digibeta: Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm Bris Reklamfilmer von Ingmar Bergman mit Bibi Andersson, Barbro Larsson, John Botvid, Schweden 1951-53, schwedisch mit englischen Untertiteln, Kopie: Swedish Institute, Stockholm Daniel (Episode aus Stimulantia) von Ingmar Bergman mit Ingmar Bergman, Käbi Laretei, Daniel Sebastian Bergman, Schweden 1964–67, schwedisch mit englischen Untertiteln,