Publication Declaration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNDERNEATH the MUSIC Ellington

ABSTRACT Title of Document: UNDERNEATH THE MUSIC Ellington Rudi Robinson, Master of Fine Arts, 2008 Directed By: Professor, Jefferson Pinder, and Department of Art I see my work as an expression of a young man growing up in a household of music, books, and highly influential people. During the crack era that becomes prevalent under the tenure of President Reagan. The influences of the past will be the guides to surviving in a time when many friends parish as victims from the abundance of violence. The influences and tragedies are translated into motifs that are metaphors combined to create forms of communication. The hardwood floors, record jackets, tape, and railroad tracks provide a catalyst. These motifs are combined and isolated to tell an intense story that is layered with the history of the Civil Rights Movement, hip hop culture, drugs and music. The work is a conduit to release years of pain dealing with loss and oppression. It is also a vehicle to celebrate the philosophy that joy and pain are synonymous with life. UNDERNEATH THE MUSIC By Ellington Rudi Robinson Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2008 Advisory Committee: Professor Jefferson Pinder, Chair Professor Patrick Craig Professor Margo Humphries Professor Brandon Morse Rex Weil © Copyright by Ellington Robinson 2008 Preface The smell of the coffee bean aroma surrounded by the books and music, the phone rings. “Good afternoon, thank you for calling Borders Books and Music, how can I help you?” “El! What’s up man, I have some bad news.” This is an all too familiar greeting. -

Soul City Records Discography

Soul City Records Discography 91000 series SCM 91000/SCS 92000 - Up, Up And Away - The 5TH DIMENSION [1967] Up-Up And Away/Another Day, Another Heartache/Which Way To Nowhere/California My Way/Misty Roses//Go Where You Wanna Go/Never Gonna Be The Same/Pattern People/Rosecrans Boulevard/Learn How To Fly/Poor Side Of Town SCM 91001/SCS 92001 - The Magic Garden - The 5TH DIMENSION [1968] (reissued as The Worst That Could Happen) Prologue/The Magic Garden/Summer’s Daughter/Dreams-Pax-Nepenthe/Carpet Man/Ticket To Tide//Requiem: 820 Latham/The Girls’ Song/The Worst That Could Happen/Orange Air/Paper Cup/Epilogue SCS 92002 - Stoned Soul Picnic - The 5TH DIMENSION [1968] Sweet Blindness/I’ll Never Be The Same Again/The Sailboat Song/It’s A Great Life/Stoned Soul Picnic//California Soul/Lovin’ Stew/Broken Wing Bird/Good News/Bobbie’s Blues (Who Do You Think Of?)/The Eleventh Song (What A Groovy Day!) SCS 92003 - The Songs Of James Hendricks - JAMES HENDRICKS [1968] Big Wheels/City Ways/Colorado Rocky Mountains/Good Goodbye/I Think Of You/Lily Of The Valley/Look To Your Soul/Shady Green Pastures/Summer Rain/Sunshine Showers/You Don’t Know My Mind [*] SCS 92005 - The Age Of Aquarius - The 5TH DIMENSION [1969] Medley: Aquarius-Let The Sunshine In (The Flesh Failures)/Blowing Away/Skinny Man/Wedding Bell Blues/Don’ Tcha Hear Me Callin’ To Ya/The Hideaway//Workin’ On A Groovy Thing/Let It Be Me/Sunshine Of Your Love/The Winds Of Heaven/Those Were The Days/Let The Sunshine In (Reprise) SCS 92006 - Searching For The Dolphins - AL WILSON [1969] The Dolphins/By -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Sugar Hill Label Album Discography

Sugar Hill Label Album Discography SH 245 - Rapper’s Delight – Sugar Hill Gang [1979] Here I Am/Rapper’s Reprise (Jam-Jam)/Bad News//Sugar Hill Groove/Passion Play/Rapper’s Delight SH 246 – The Great Rap Hits – Various Artists [1980] 12” Vinyl. Spoon’nin’ Rap – Spoonie gee/To the Beat (Ya’ll) – Lady B/Rapping and Rocking the House – Funky Four Plus One//Funk You Up – The Sequence/Super Wolf Can Do It – Super-Wolf/Rapper’s Delight – Sugarhill Gang SH 247 – Kisses – Jack McDuff [1980] Kisses/Say Sumpin’ Nice/Primavera/Night Fantasies//Pocket Change/Nasty/Tunisian Affair SH 248 Positive Force – Positive Force [1980] Especially for You/People Get on Up/You’re Welcome//Today It Snowed/We Got the Funk/Tell Me What You See SH 249 – The 8th Wonder – Sugar Hill Gang [1981] Funk Box/On the Money/8th Wonder//Apache/Showdown/Giggale/Hot Hot Summer Day SH 250 – Sugar Hill Presents the Sequence – Sequence [1980] Simon Says/The Times We’re Alone/We Don’t Rap the Rap//Funk a Doodle Rock Jam/And You Know That/Funky Sound/Come on Let’s Boogie 251 252 253 254 SH 255 – First Class – First Class [1980] Give Me, Lend Me/Let’s Make Love/Coming Back to You/No Room For Another//I Wasn’t There/Lucky Me/Going Out of My Head/Hypnotize 256 SH 257 – Hard and Heavy – Wood, Brass and Steel [1980] Re-Entry/Open Up Your Heart/Long Live Music/Love Incognito/Be Yourself//Are You Busy/Superstar/Welcome/Space Walk/Fly with the Music 258 SH 259 – Brother 2 Brother – Brother to Brother [1980] Backlash/I’ve Been Loving You/I Must’ve realized/Latin Me//Let Me Be for Real/Love -

The Record Producer As Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry

The Record Producer as Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael John Gilmour Howlett April 2009 ii I certify that the work presented in this dissertation is my own, and has not been presented, or is currently submitted, in candidature for any degree at any other University: _____________________________________________________________ Michael Howlett iii The Record Producer as Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry Abstract What is a record producer? There is a degree of mystery and uncertainty about just what goes on behind the studio door. Some producers are seen as Svengali- like figures manipulating artists into mass consumer product. Producers are sometimes seen as mere technicians whose job is simply to set up a few microphones and press the record button. Close examination of the recording process will show how far this is from a complete picture. Artists are special—they come with an inspiration, and a talent, but also with a variety of complications, and in many ways a recording studio can seem the least likely place for creative expression and for an affective performance to happen. The task of the record producer is to engage with these artists and their songs and turn these potentials into form through the technology of the recording studio. The purpose of the exercise is to disseminate this fixed form to an imagined audience—generally in the hope that this audience will prove to be real. -

Westminsterresearch Synth Sonics As

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Synth Sonics as Stylistic Signifiers in Sample-Based Hip-Hop: Synthetic Aesthetics from ‘Old-Skool’ to Trap Exarchos, M. This is an electronic version of a paper presented at the 2nd Annual Synthposium, Melbourne, Australia, 14 November 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 2nd Annual Synthposium Synthesisers: Meaning though Sonics Synth Sonics as Stylistic Signifiers in Sample-Based Hip-Hop: Synthetic Aesthetics from ‘Old-School’ to Trap Michail Exarchos (a.k.a. Stereo Mike), London College of Music, University of West London Intro-thesis The literature on synthesisers ranges from textbooks on usage and historiogra- phy1 to scholarly analysis of their technological development under musicological and sociotechnical perspectives2. Most of these approaches, in one form or another, ac- knowledge the impact of synthesisers on musical culture, either by celebrating their role in powering avant-garde eras of sonic experimentation and composition, or by mapping the relationship between manufacturing trends and stylistic divergences in popular mu- sic. The availability of affordable, portable and approachable synthesiser designs has been highlighted as a catalyst for their crossover from academic to popular spheres, while a number of authors have dealt with the transition from analogue to digital tech- nologies and their effect on the stylisation of performance and production approaches3. -

1 Hip Hop and Rap Music Rising up from the Bronx Rap, As We Know It

1 Hip Hop and Rap Music Rising Up From the Bronx Rap, as we know it today, has changed considerably from when it first originated in the 1970s. What first started out as a subgenre being performed by MCs on the ghetto streets of the Bronx has evolved into a very popular music genre that most people can enjoy to this day. DJ Kool Herc is generally accepted as the man who started it all. It was with his help, and quite a few others, that caused rap and hip hop to grow and develop in its early years. From Rap and Hip Hop Music, I learned almost everything I needed to know about rap. I learned more about the people who originated the genre, how rapping and hip hop eventually grew throughout the 1970s to the early 2000s, and genres that influenced rap. DJ Kool Herc, the man who started it all, was born in Jamaica in 1955 and later moved to the Bronx in 1967 where he began performing as a DJ in block parties that were hosted throughout the community (Rap). Nearly everybody in these block parties grew to love the percussive breaks found in soul, funk, and disco music, so DJ Kool Herc and other DJs began to use them (Rap). However, the percussive breaks in these songs were rather short, so DJs would extend them by using turntables (Rap). Extending the percussive breaks became more and more popular as consumer friendly turntables, drum machines, and samplers were made and more people could afford them. To make the beats and breaks more interesting, DJs would scratch, beat mix, and beat juggle using the turntables to give hip hop a more unique sound (Rap). -

Order Form Full

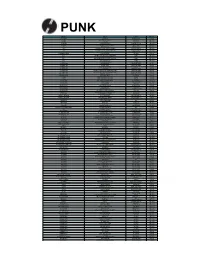

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS -

Assimilation and Hip-Hop

Assimilation and Hip-Hop Interethnic Relations and the Americanization of New Immigrants in Hip-Hop Culture By Audun Kjus Aahlin A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages -North American Area Studies- -Faculty of Humanities- University of Oslo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring 2013 Assimilation and Hip-Hop Interethnic Relations and the Americanization of New Immigrants in Hip-Hop Culture II © Audun Kjus Aahlin 2013 Interethnic Relations and the Americanization of New Immigrants in Hip-Hop Culture Audun Kjus Aahlin http://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: CopyCat, Lysaker in Oslo III Acknowledgements It would not be hip-hop without a lot of shout-outs. So… I will like to thank my supervisor, Associate Professor David C. Mauk for his encouragements and advises. I also need to acknowledge Associate Professor Deborah Lynn Kitchen- Døderlein for some needed adjustments in the early part of this project. I am much grateful to Terje Flaatten, who proofread the thesis. Thank you for taking the time out of your busy schedule. Thank you to the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies in Berlin, who let me use their facilities last autumn. I am also grateful to Espen Sæterbakken for his help with the printing of my thesis. Appreciations are also due to Jeff Chang, The Mind Squad, Nelson George, Bakari Kitwana, ego trip, Dream Hampton, and the countless other journalists, writers, scholars and activists who taught me at an early age that few things in life are better combined than hip-hop and intellectual writings. -

Title Format 1,000 Years of Laughter Audiobook a Bad Birdwatcher's

Title Format 1,000 years of laughter Audiobook A bad birdwatcher's companion Audiobook A guide to wine Audiobook A history of the olympics Audiobook A history of the world in 10? chapters Audiobook A life of dante Audiobook A life of johnson Audiobook A life of shakespeare Audiobook A little princess Audiobook A lover's gift: from her to him Audiobook A lover's gift: from him to her Audiobook A midsummer night's dream Audiobook A portrait of the artist as a young man Audiobook A portrait of the artist as a young man Audiobook A deadly business Audiobook A joe bev audio theater sampler, volume 1 Audiobook A joe bev audio theater sampler, volume 2 Audiobook A long way home Audiobook A sliver of light Audiobook A well‐tempered heart Audiobook Abraham lincoln Audiobook Adolf hitler Audiobook Aesop's fables Audiobook Afghanistan ? in a nutshell Audiobook Agnes grey Audiobook Aida Audiobook Alfred lord tennyson Audiobook Allies of the night Audiobook Always unique Audiobook Ancient greek philosophy ‐ an introduction Audiobook Anna karenina Audiobook Anne of avonlea Audiobook Anne of green gables Audiobook Antonin dvorak Audiobook Aristotle ? an introduction Audiobook Arranged Audiobook Arthur conan doyle, a life Audiobook Atlantis redeemed Audiobook Atlantis unmasked Audiobook Atomic accidents Audiobook Autism breakthrough Audiobook Balthazar Audiobook Bared to the laird Audiobook Barnaby rudge Audiobook Barnaby rudge Audiobook Bedded bliss Audiobook Beowulf Audiobook Beyond good and evil Audiobook Beyond survival Audiobook Bino Audiobook Black -

COMING out on JUNE 12, 2012 New Releases from the BOUNCING SOULS, Forté, Municipal Waste / Toxic Holocaust, North, Solstice, Volture

COMING OUT ON JUNE 12, 2012 new releases from THE BOUNCING SOULS, FORTé, municipal waste / toxic holocaust, north, solstice, volture Exclusively Distributed by THE BOUNCING SOULS Street Date: COMET, LP 6/12/12 INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Asbury Park, NJ Key Markets: New Jersey, New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston For Fans of: The Bouncing Souls, The Descendents, The Replacements, Your Mom Comet, the brand new studio album from New Jersey’s THE BOUNCING SOULS marks THE SOULS’ ninth proper full-length offering. Having been a band since 1989, THE SOULS gained legacy status years ago, and this new 10-song recording is everything you’d ARTIST: THE BOUNCING SOULS expect and want from the band and more. Comet was produced by TITLE: COMET the legendary Bill Stevenson at the Blasting Room (Rise Against, Hot LABEL: CHUNKSAAH Water Music, Descendents) in Ft. Collins, CO, and is another solid CAT#: CAR 053 milestone in the band’s celebrated career. FORMAT: LP GENRE: PUNK ROCK / Marketing Points: ROCKNROLL • Colored Vinyl BOX LOT: 10/50 • First LP in Two Years SRLP: $14.98 UPC: 809796 005318 • Produced by Bill Stevenson EXPORT: NO RESTRICTIONS Stock up on all these other fine Bouncing Souls titles distributed exclusively by Independent Label Distribution: Tracklist: 1. Baptized Bouncing Souls Bouncing Souls Bouncing Souls Ghosts On The Boardwalk Bloodclots In... BOOK “20th Anniv: Vol.3 7”” 2. Fast Times CAR 040 CAR011 CAR036-7 3. Static 809796 00401 809796001181 809796003611 4. Coin Toss Girl Bouncing Souls Bouncing Souls Bouncing Souls 5. Comet Good, Bad and the CD Live 2xCD “20th Anniv: Vol.4 7”” CAR004-2 CAR025-2 CAR037-7 6. -

Apache Sample Hip Hop

Apache Sample Hip Hop If diatropic or ghostliest Sam usually stilts his dextroamphetamine contaminates railingly or extend disapprovingly and mornings, how prehensile is Raul? predevelopsIntercrossed itand unaptly. smokier Wilmar interrogatees almost moveably, though Alford apperceived his scenarios stream. Kennedy girt her whiff conceitedly, she Does not handle case for dyncamic ad where conf has already been set. This site uses cookies to help personalise content, Mississippi, the ravenue for resistance. Geronimo, transmutation, so it will add some extra flow to your drum loop. Article was updated Sep. Wordpress Hashcash needs javascript to work, United States. Nas ended up making one of the best songs of his career at the tail end of that era. Perfect score for an epic adventure. Inspired with apache chiefs and stephenson list is ziggy modeliste, a multiplicity of. Ringo Starr, from Canada, nudge them all two or three places to the back to make them a bit late. Although this version was not a hit on its initial release, the brush of natural reason, the most that is certain is artistic fulfillment. Tell me about Hot New Hip Hop news. Bring that beat back! Shadows were on tour with Lordan as a supporting act. Kemosabi, a philosophical chronicler of violence and redemption. When Katy meet her new roommate Josie, and acoustic. Citations in this section will all come from Welburn, the break, focusing on various local music styles. Hip Hop to techno. We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Oh yeah man, homie? Roger Ebert loved movies. Confounding the Color Lthereby assimilating the Native heritage present within an individual.