Migration and Musical Creativity in Bronx Neighbourhoods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

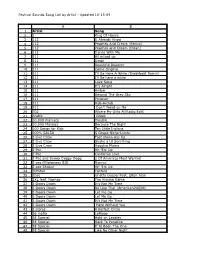

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

April 1, 2011 Thru June 30, 2011 Performance Report B-11

Grantee: New York City, NY Grant: B-11-MN-36-0103 April 1, 2011 thru June 30, 2011 Performance Report 1 Community Development Systems Disaster Recovery Grant Reporting System (DRGR) Grant Number: Obligation Date: Award Date: B-11-MN-36-0103 Grantee Name: Contract End Date: Review by HUD: New York City, NY 03/10/2014 Reviewed and Approved LOCCS Authorized Amount: Grant Status: QPR Contact: $9,787,803.00 Active Lindsay Haddix Estimated PI/RL Funds: $0.00 Total Budget: $9,787,803.00 Disasters: Declaration Number No Disasters Found Narratives Summary of Distribution and Uses of NSP Funds: The Ely Avenue project was initially conceptualized in 2006 to build ten two-family homes in the Baychester neighborhood of the Bronx. The construction began on schedule and continued until the project was 75% built. The Ely Avenue project will be carried out under NSP Eligible Use B: Acquisition and Rehabilitation and CDBG Activity Sec. 570.201(a) Acquisition. A new developer, using a combination of $1,500,000 of NSP3 funds, a private mortgage and equity would acquire the project and complete the remaining construction. Upon completion, all 20 units would be rented to low, moderate and middle-income individuals and families at, or below 120% of the area median income (AMI). The Kelly Street 25% project consists of a 79 unit, five building portfolio located on Kelly Street in Longwood/Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx. The portfolio was initially acquired by a speculative investor and has since fallen into a severe state of physical distress.An affordable housing owner, WFH Advisors would purchase the portfolio of buildings using a combination of funds that includes $2,446,825 in NSP3 funds. -

Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- Lecture for C-Span

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Occasional Essays Bronx African American History Project 10-28-2019 Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- Lecture for C-Span Mark Naison Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_essays Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the Ethnomusicology Commons Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- My Lecture for C-Span What I am about to describe to you is one of the most improbable and inspiring stories you will ever hear. It is about how young people in a section of New York widely regarded as a site of unspeakable violence and tragedy created an art form that would sweep the world. It is a story filled with ironies, unexplored connections and lessons for today. And I am proud to share it not only with my wonderful Rock and Roll to Hip Hop class but with C-Span’s global audience through its lectures in American history series. Before going into the substance of my lecture, which explores some features of Bronx history which many people might not be familiar with, I want to explain what definition of Hip Hop that I will be using in this talk. Some people think of Hip Hop exclusively as “rap music,” an art form taken to it’s highest form by people like Tupac Shakur, Missy Elliot, JZ, Nas, Kendrick Lamar, Wu Tang Clan and other masters of that verbal and musical art, but I am thinking of it as a multilayered arts movement of which rapping is only one component. -

I Concerti Dell'arena E Le Schede Degli Artisti

I CONCERTI DELL’ARENA E LE SCHEDE DEGLI ARTISTI (8 giugno) - ARENA Issac Delgado Issac Delgado è una delle icone della salsa mondiale. Figlio d’arte, sua madre - Lina Ramirez era attrice, ballerina e cantante - Issac è nato nel 1962 a Marianao, il popolare quartiere de La Havana. Ha registrato decine di album e vanta anche due cd pubblicati con la mitica etichetta RMM: il suo nome è ormai un punto di riferimento per i salseri di tutto il mondo. La sua carriera professionale è iniziata nel 1983 come componente dell’orchestra di Pacho Alonso. Nel 1988 è cantante solista di NG La Banda. Il suo primo gruppo risale al 1991. Da qualche anno vive a Miami con la sua famiglia. Innumerevoli i grandi successi, sopra tutti “La Vida Es Un Carnaval” incisa nel 1999 e che ancora oggi è la versione più conosciuta di questa canzone nel mondo. Issac Delgado ha una particolare ammirazione per l’Italia. E’ uno dei Paesi dove ha eseguito più concerti e questo suo amore lo ha dichiarato realizzando la versione salsa – cantata in italiano – di “Quando”, uno dei maggiori successi di Pino Daniele. (9 giugno) - ARENA Rodry-Go Rodrigo Rodriguez Puerta, conosciuto come Rodry-Go è un artista energetico, carismatico e a tratti romantico. Ma, soprattutto, è il fondatore di un nuovo genere musicale: il reggaelove. Colombiano di Cartagena, ha fatto parte, come cantante e percussionista, del gruppo Mercadonegro con centinaia di concerti internazionali al suo attivo. Nel 2001 è stato al “Pavarotti & Friends” con la leggendaria regina della salsa, Celia Cruz; ha suonato con star del calibro di Cheo Feliciano, Josè Aalberto “El Canario”, Richie Ray, Tito Nieves, Ray Sepulveda, Albita Rodriguez, Dave Valentin, Chico Freeman, Giovanni Hidalgo, Alfredo De La Fe, Los Hermanos Moreno, e molte altre stelle del mondo Strategie di Comunicazione Daniela Esposito Vittorio Morelli [email protected] Pag. -

SESSION HANDOUT Salsa & Merengue Mash Up

SESSION HANDOUT Salsa & Merengue Mash Up Walter Diaz (Wally) Presenter, USA SESSION HANDOUT Presenter Walter Diaz (Wally) Schedule 50 min: Theoretical explanation about all these fantastic rhythms and their influences. 70 min: Master Class, including the Warm Up and Cool Down. (Total: 2 hours) Session Objective The session will give ZIN Members valuable information and knowledge about Salsa and Merengue, thus providing participants with the tools to easily identify these rhythms and put them into practice. History & Background HISTORY OF MERENGUE Merengue is a style of music and dance originated in the Caribbean, specifically in the Dominican Republic in the early nineteenth century. Originally, the Merengue was interpreted with stringed instruments (guitars). Years later, the guitars were replaced by the Accordion along with the Guira and the Tambora (drum of two patches), the structure of the whole instrumental típico. This set, with three instruments, represents the synthesis of three cultures that shaped the flavor of the Dominican culture. European influence is represented by the Accordion, the African by the Tambora (drum of two patches), and the aboriginal by the Taino or Güira. Although in some areas of the Dominican Republic, especially in the Cibao, there are still typical sets, this has evolved throughout the twentieth century with the introduction of new instruments like the saxophone and later with the appearance of bands with complex wind sections. The origin of the word merengue goes back to colonial times and comes from the word Muserengue, the name given to dances among some African cultures. The Dominican Merengue genre has played a major role within the environment of Afro Caribbean. -

Star House Brand Principles and Themes

Star House Refurb. Brand Direction. Version 1 3 December 2015 PositioningAll about and Sense integration.the people. “ You are a product of your environment” W. Clement Stone. Star House Refurb. We need to live our brand purpose. Reinvent the rules. Make mobile better. Star House Refurb. And do it every day. Translate the purpose into the environment. A space where reinvention can happen. Star House Refurb. The tone. How are we approaching the refurb from a brand point of view? Star House Refurb. The tone. • Playful, but grown up. • A space made for reinvention. • Quirky without being ‘look at me, look at me.’ • Considered - Warm neutrals with bold accents and colour zoning in specific areas to contrast with bright furniture. Star House Refurb. Principles. 1 2 3 4 4 holistic rules to approach the refurb from layout to branding to the chairs we sit on. Star House Refurb. 1 Flexibility. A space we can all use differently. How do we move around the building • No one person works the sameand way. within our own areas? • Need to address different departmentsHow do needswe give our people • Agile working environments which change to reflect their occupants and thefunction perfect on a daily journey basis. at the start, middle and end of their working day? Star House Refurb. 2 Collaborate. A space to work together. How do we move around the building and within our own areas? • We work best when we’re working with others. How do we give our people • Amazing things happen in unexpected places. • Increase breakout collaboration areas and the perfect journey at the start, improve layout for seating and meeting spaces. -

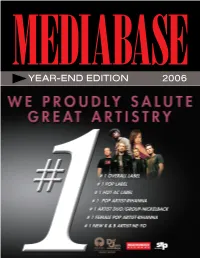

Year-End Edition 2006 Mediabase Overall Label Share 2006

MEDIABASE YEAR-END EDITION 2006 MEDIABASE OVERALL LABEL SHARE 2006 ISLAND DEF JAM TOP LABEL IN 2006 Atlantic, Interscope, Zomba, and RCA Round Out The Top Five Island Def Jam Music Group is this year’s #1 label, according to Mediabase’s annual year-end airplay recap. Led by such acts as Nickelback, Ludacris, Ne-Yo, and Rihanna, IDJMG topped all labels with a 14.1% share of the total airplay pie. Island Def Jam is the #1 label at Top 40 and Hot AC, coming in second at Rhythmic, Urban, Urban AC, Mainstream Rock, and Active Rock, and ranking at #3 at Alternative. Atlantic was second with a 12.0% share. Atlantic had huge hits from the likes of James Blunt, Sean Paul, Yung Joc, Cassie, and Rob Thomas -- who all scored huge airplay at multiple formats. Atlantic ranks #1 at Rhythmic and Urban, second at Top 40 and AC, and third at Hot AC and Mainstream Rock. Atlantic did all of this separately from sister label Lava, who actually broke the top 15 labels thanks to Gnarls Barkley and Buckcherry. Always powerful Interscope was third with 8.4%. Interscope was #1 at Alternative, second at Top 40 and Triple A, and fifth at Rhythmic. Interscope was led byAll-American Rejects, Black Eyed Peas, Fergie, and Nine Inch Nails. Zomba posted a very strong fourth place showing. The label group garnered an 8.0% market share, with massive hits from Justin Timberlake, Three Days Grace, Tool and Chris Brown, along with the year’s #1 Urban AC hit from Anthony Hamilton. -

The Historical Roots of Hip Hop Overview

THE HISTORICAL ROOTS OF HIP HOP OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION What are the historical roots of Hip Hop? OVERVIEW Hip Hop emerged directly out of the living conditions in America’s inner cities in the 1970s, particularly the South Bronx region of New York City. As a largely white, middle-class population left urban areas for the suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s—a phenomenon known as “white flight”— the demographics of communities such as the Bronx shifted rapidly. The Bronx, one of New York City’s five “boroughs,” became populated mainly by Blacks and Hispanics, including large immigrant populations from Caribbean nations including Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, and others. Simultaneous with the “white flight,” social and economic disruptions abounded. Construction on the Cross Bronx Expressway, which began in the postwar period and continued into the early 1970s, decimated several of the minority neighborhoods in its path; city infrastructure was allowed to crumble in the wake of budget cuts, hitting the less privileged parts of the city most directly; and strikes organized by disaffected blue-collar workers crippled the entire metropolitan area. Amidst the higher crime and rising poverty rates that came with urban decay, young people in the South Bronx made use of limited resources to create cultural expressions that encompassed not only music, but also dance, visual art, and fashion. In music, Latin and Caribbean traditions met and mingled with the sounds of sixties and seventies Soul, Disco, and Funk. The venues for the emerging art of Hip Hop were public parks and community recreation centers, sheets of cardboard laid out on city sidewalks became dance floors, and brick walls were transformed into artists’ canvases. -

My New Updated 2012 List. All Types of Latin Music, Including Merengue, Merengue House, Latin Dance and More!

My new updated 2012 list. All types of Latin music, including Merengue, Merengue House, Latin Dance and more! Tropical Latin January 2012 Tropical Latin March 2012 1 Lovumba/ Daddy Yankee 1 Las Cosas Pequeñas/ Prince Royce 2 Me Toca Celebrar/ Tito \ "El Bambino\ " 2 Mi Santa/ Romeo Santos f./ Tomatito 3 Bebe Bonita/ Chino Y Nacho f./ Jay Sean 3 Mi Reto/ Luis Enrique 4 Por Nada/ Henry Santos 4 Solo Con Un Beso/ Jerry Rivera 5 Aires De Navidad/ N\ 'Klabe 5 Vallenato En Karaoke/ Elvis Crespo f./ Los Del 6 Aires De Navidad/ Remix/ N\ 'Klabe f./ Sergio Vargas Puente 7 Papi/ Original Radio/ Jennifer López 6 Me Voy De La Casa/ Tito \ "El Bambino\ " 8 All My Life/ Migz 7 Hotel Nacional/ Gloria Estefan 9 Energía/ Remix/ Alexis & Fido f./ Wisin & Yandel 8 Lindísima/ Grupomanía f./ Zone D\' Tambora 10 Me Gusta Tanto/ Mambo Remix/ Paulina Rubio f./ 9 International Love/ Pitbull f./ Chris Brown Gocho 10 Claridad/ Richy Peña Merengue/ Mambo Remix/ 11 I Like How It Feels/ Enrique Iglesias f./ Pitbull Luis Fonsi 12 Ya No Quiero Tu Querer/ José Alberto \ "El 11 Quédate Conmigo/ Zacarías Ferreira Canario\ " & Raulín Rosendo 12 Dilema/ Fabián 13 Toma Mi Vida/ Milly Quezada f./ Juan Luis Guerra 13 Ni Loca/ DJ Chino/ Merengue Pop Remix/ Fanny Lú 14 Amor En La Luna/ Ephrem J 14 Tengo Ganas/ Remix/ Ambar f./ El Cata 15 No La Quiero Perder/ Maffio Alkattraks Remix/ 808 15 No Apagues La Luz/ Jco (Ocho Cero Ocho) 16 Que Joyitas!/ Limi-T 21 16 Antes Solías/ Arcángel \ 'La Maravilla\ ' 17 Adiós/ D\'Mingo 17 El Pum/ Radio Edit/ Kalimete 18 Buscando Corazon/ Grupo -

Music and Theme Cruises

WHET TRAVEL OVERVIEW Whet = Excitement! Whet Travel Inc., founded in 2004, is an experiential travel company that was formed to create large scale one of a kind unforgettable experiences for music lovers and those who belong to a strong affinity. Each year thousands of people from around the world embark on a journey unlike anything on earth and return as raving members of the Whet Fam. Whet Travel is affiliated with some of the world's top companies, is always on the cutting edge of technology and upholds the highest service standards. • Music and Theme Cruises - Whet Travel is one of only a handful of companies that has a proven track record of initiating, negotiating, promoting, and producing full and half ship charters of some of the best cruise ships in the world • Worked with nearly all major cruise lines, including Norwegian, Carnival, Royal Caribbean, Celebrity, Princess Cruise Lines, and MSC • Whet Travel produces Aventura Dance Cruise - The World's Largest Salsa, Bachata, and Latin Dance Cruise; Shiprocked - The Ultimate Rock and Roll Vacation; Motorhead's Motorboat - The Loudest Ship in The World; The Zen Cruise - A Transformational Journey at Sea, Inception at Sea- Spring break will never be the same... • Cruise Event GPS specializes in corporate events and incentives on cruise ships. WWW.WHETTRAVEL.COM GROOVE CRUISE LA 2015 (#GCLAXi) Los Angeles to Ensenada, Mexico & Catalina Island on board the Carnival Inspiration OCT 23-26, 2015 World's Largest Floating Dance Music Festival www.TheGrooveCruise.com GROOVE CRUISE MIAMI 2016 -

112 Dance with Me 112 Peaches & Cream 213 Groupie Luv 311

112 DANCE WITH ME 112 PEACHES & CREAM 213 GROUPIE LUV 311 ALL MIXED UP 311 AMBER 311 BEAUTIFUL DISASTER 311 BEYOND THE GRAY SKY 311 CHAMPAGNE 311 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 DON'T STAY HOME 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 DOWN 311 LOVE SONG 311 PURPOSE ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 1 PLUS 1 CHERRY BOMB 10 M POP MUZIK 10 YEARS WASTELAND 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 FT. SEAN PAUL NA NA NA NA 112 FT. SHYNE IT'S OVER NOW (RADIO EDIT) 12 VOLT SEX HOOK IT UP 1TYM WITHOUT YOU 2 IN A ROOM WIGGLE IT 2 LIVE CREW DAISY DUKES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW DIRTY NURSERY RHYMES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW FACE DOWN *** UP (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME ***** (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 PAC 16 ON DEATH ROW 2 PAC 2 OF AMERIKAZ MOST WANTED 2 PAC ALL EYEZ ON ME 2 PAC AND, STILL I LOVE YOU 2 PAC AS THE WORLD TURNS 2 PAC BRENDA'S GOT A BABY 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (EXTENDED MIX) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (NINETY EIGHT) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) 2 PAC CAN'T C ME 2 PAC CHANGED MAN 2 PAC CONFESSIONS 2 PAC DEAR MAMA 2 PAC DEATH AROUND THE CORNER 2 PAC DESICATION 2 PAC DO FOR LOVE 2 PAC DON'T GET IT TWISTED 2 PAC GHETTO GOSPEL 2 PAC GHOST 2 PAC GOOD LIFE 2 PAC GOT MY MIND MADE UP 2 PAC HATE THE GAME 2 PAC HEARTZ OF MEN 2 PAC HIT EM UP FT. -

Sampling: the Foundation of Hip Hop Overview

SAMPLING: THE FOUNDATION OF HIP HOP OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How is the re-use and re-purposing of existing music at the heart of the Hip Hop recording experience? OVERVIEW In many ways Hip Hop is quintessentially American music. It was first created in the Bronx, NY, a borough of New York City that at the time was economically depressed, dangerous and mostly forsaken by the local government. The pioneers of Hip Hop, young people of color living in struggling communities and limited in their opportunities, embraced modern music technologies (first turntables, then drum machines and later samplers) but used them creatively, often in ways their manufacturers never intended. Indeed, the origin story of Hip Hop is one of opening doors that seemed tightly shut. To many listeners, the first commercial rap releases were surprising, something that seemed new, even unexpected. Many of the early rappers who performed at the block parties that spawned the genre had not themselves conceived of Hip Hop as something one could record and sell. For instance, in Soundbreaking Episode 6 Public Enemy’s Chuck D recalls that before the Sugar Hill Gang’s breakthrough release, “we couldn’t even imagine a rap record.” However, as radical as it sounded to the average American listener in 1980, Hip Hop had deep connections to African- American and Afro-Caribbean music traditions in its performance style and in its use of turntables and prerecorded material as the primary “instrument” in the band. In this lesson students explore the creative concepts and technological practices on which Hip Hop music was constructed, investigating what it means to “sample” from another style, who has used sampling and how.