Cahiers D'études Africaines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audio Today a Focus on African American & Hispanic Audiences April 2014

STATE OF THE MEDIA: AUDIO TODAY A FOCUS ON AFRICAN AMERICAN & HISPANIC AUDIENCES APRIL 2014 STATE OF THE MEDIA: AUDIO TODAY Q2 Copyright © 2014 The Nielsen Company 1 GROWTH AND THE AUDIO LANDSCAPE NATIONAL AUDIENCE HITS ALL-TIME HIGH Growth is a popular word today in America, whether you’re talking about the stock market, entertainment choices, or census trends. Through it all, radio consumption continues to increase; nearly 92% of all Americans 12 or older are tuning to radio in an average week. That’s 244.4 million of us, a record high! 244 MILLION AMERICANS LISTEN TO RADIO EACH WEEK This growth is remarkable considering the variety and number of media choices available to consumers today over-the-air and online via smartphones, tablets, notebooks/desktop computers and digital dashboards. Radio’s hyper-local nature uniquely serves each market which keeps it tied strongly to our daily lives no matter how (or where) we tune in. The radio landscape is also a diverse community of listeners from every corner of America, who reflect the same population trends of the country as a whole. Radio is one of the original mass mediums and as the U.S. population grows and the makeup of our citizens change, radio audiences follow suit. Alongside the national growth headline, both African American and Hispanic audiences have also reached a historic high with more than 71 million tuning in each week. Source: RADAR 120, March 2014, M-SU MID-MID, Total Listeners 12+/Hispanic 12+/African American 12+ 2 STATE OF THE MEDIA: AUDIO TODAY Q2 RADIO’S GROWTH CHART IS DIVERSIFIED Weekly Cume (000) March 2013 June 2013 Sept 2013 Dec 2013 March 2014 All Listeners 12+ 243,177 242,876 242,530 242,186 244,457 Hispanic 12+ 39,586 39,577 39,506 39,380 40,160 African American 12+ 30,987 30,862 30,823 30,742 31,186 71 MILLION AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISPANICS The focus for this quarter’s Audio Today report is the African American and Hispanic listener; combined these listeners account for nearly a third (29.6%) of the total national audience. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) MAR CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 20 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 18, 19 BENNY BENASSI DA 16 THE CLARK SISTERS GS 14 EST GEE HS 4; H100 34; ODS 14; RBH 17; RS H.E.R. B200 166; RBL 23; ARB 12, 14; H100 50; -L- 13; STM 13 HA 23; RBH 22; RBS 6, 18 THE 1975 RO 40 GEORGE BENSON CJ 3, 4 CLEAN BANDIT DES 16 LABRINTH STX 20 FAITH EVANS ARB 28 HIKARU UTADA DLP 17 21 SAVAGE B200 63; RBA 36; H100 86; RBH DIERKS BENTLEY CS 21, 24; H100 -

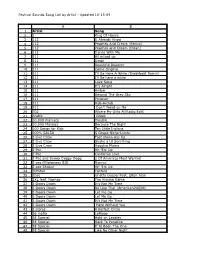

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Art Does Not Have to Be Confined to Museums and Galleries

ARTART DOESDOES NOTNOT HAVEHAVE TOTO BEBE CONFINEDCONFINED TOTO MUSEUMSMUSEUMS ANDAND GALLERIES.GALLERIES. THE SHEBOYGAN PROJECT brings the street-art movement to Sheboygan, Wisconsin, by using the urban landscape as a canvas for exciting works of art that reflect the city’s people and culture. Wooster Collective founders Marc and Sara Schiller have celebrated ephemeral art placed on streets in cities throughout the world since 2001. As part of a two-year project that began in 2012, Wooster Collective, the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, renowned street artists, area residents, civic organizations, businesses, and property owners worked together to locate potential street-art sites throughout the city. In the summer of 2013, those locations became home to exciting new works of art. Undertaken as part of the Arts Center’s Connecting Communities program, the project aimed to create a more intimate relationship between the artists and the Sheboygan community through collaboration. It is hoped that this project will continue to draw and inspire artists from inside and outside the community by increasing and strengthening the city’s public art and cultural diversity. Additionally, The Sheboygan Project seeks to further develop Sheboygan’s reputation as a destination for artists and to encourage local residents to embrace the arts culture of their city. As you visit The Sheboygan Project installations, connect and share with us! Hashtag your content on Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr at #thesheboyganproject. Stay up to date and like our page at facebook.com/thesheboyganproject. For more information, please go to www.thesheboyganproject.org. Cover image: Nick “Doodles” Mann, untitled (detail), The Sheboygan Project, 2013; acrylic and spray paint Opposite page: Chris Stain, untitled (detail), The Sheboygan Project, 2012; spray paint Follow Calumet Dr. -

Cavafy Song Bibliography Version2 1-15-20

C. P. Cavafy Music Resource Guide: Song and Music Settings of Cavafy’s Poetry Researched by Vassilis Lambropoulos Compiled by Peter Vorissis, Haris Missler, and Artemis Leontis* Modern Greek Program & C. P. Cavafy Professorship in Modern Greek Departments of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature University of Michigan Version 2: January 14, 2020 Please send additions and corrections to [email protected] * with gratitude to Dimitris Gousopoulos for major additions of the melopoiesis of Cavafy’s poetry in rock, pop, hip hop, metal, indie, and punk Cavafy Music Resource Guide 1 Cavafy Song Settings: A Music Resource Guide Adamopoulos, Loukas (Αδαμόπουλος, Λουκάς). 1981. «Επέστρεφε» (Come back). Κέρκυρα ’81: Αγώνες ελληνικού τραγουδιού—Τα 30 τραγούδια (Kerkyra ’81: Greek song contest). Αthens: Minos. Setting: «Επέστρεφε» (Come Back). Anabalon, Patricio. 2003. Itaca. Poetas griegas musicalizados. Santiago: Alerce Producciones Fonograficas S.A. Includes the songs “Itaca” (Ithaka), “Regresa” (Come back), “Una Noche/Las Ventanas” (One night / Windows). Anagnostatos, Yiannis (Αναγνωστάτος Γιάννης, also known as Lolek). 2010. «Κεριά». In the compilation Ποιήματα του Κ.Π. Καβάφη (Poems of C.P. Cavafy). Athens: Odos Panos 147 (January–March). (See “Lolek” below). Anestopoulos, Thanos (Ανεστόπουλος, Θάνος). 2001. «Κεριά» (Candles). In Οι ποιητές γυμνοί τραγουδάνε (Poets sing naked). Athens and Patra: Κονσερβοκούτι. For voice and electronic accompaniment or guitar. Composed and sung by Thanos Anestopoulos (Θάνος Ανεστόπουλος) under the pseudonym ΑΣΘΟΝ ΣΑΠΤΟΥΣ ΛΕΟΝΟΣ, an anagram of his name. First released as a cassette by the magazine «Κονσερβοκούτι» (Tin can, the magazine of OEN, Οργάνωση Επαναστατικής Νεολαίας, Organization of Revolutionary Youth). Setting: «Κεριά» (Candles). Angelakis, Manolis (Αγγελάκης, Μανώλης) & τα Θηρία (and the Beasts). -

María Fernanda Viera Journalist, Digital Host & Producer

María Fernanda Viera Journalist, Digital Host & Producer Multimedia Journalist with 4 years of experience and a Master's degree. Outgoing, creative, detail- oriented and passionate for the media industry. EDUCATION [email protected] Spanish Language Journalism & Multimedia Master 305-780-1890 Florida International University 09/2016 – 05/2018 Miami, Florida Miami, Florida Bachelor in Mass Communication Universidad Arturo Michelena www.itsmariafernanda.com/ 08/2008 – 06/2013 Valencia, Venezuela linkedin.com/in/maria- fernanda-viera-23ab9248 WORK EXPERIENCE Entertainment Journalist, Digital Host & Producer facebook.com/Presspasslatino Press Pass Latino 01/2018 – Present Miami, Florida medium.com/@mvier017 Achievements/Tasks Collaborating as a reporter, editor and writer for the bilingual lifestyle blog “Press Pass Latino”. Interviewed artists such as: Amber Heard, Carlos Vives, Alejandra Guzmán, CNCO, Bacilos, Il Volo, instagram.com/itsmariafernann da Diego Torres, Casper Smart, Lali Espósito, Leslie Grace, Marco de la O, Zion y Lennox, Ricardo Montaner, Natti Natasha, Chyno Miranda, Mau & Ricky, In Real Life, Kany García and more. Covered : Univision's "Premios Juventud" 2018" , "Nuestra Belleza Latina 2018" & "Mira Quién Baila SKILLS 2019" as a Digital Reporter. 4 years editing with Contact: Daysi Calavia- Robertson – [email protected] Adobe Premiere Media Center- Welcome Desk Miami Open 3 years on production & filming 03/2017 – 03/2018 Miami, Florida Achievements/Tasks Assisted in managing media conferences for ATP & WTA players such as: Roger Federer, Rafael Photoshop, Word, Excel, Nadal, Simona Halep, Sloane Stephens, Juan Martín del Potro, Angelique Kerber, among others. Power Point Contact: Fernanda Rodriguez – [email protected] Social Media Content TV Host & Reporter Creator Ecovision TV 05/2015 – 01/2016 Valencia, Venezuela Creative, responsible & Achievements/Tasks outgoing Hosted live fashion events, covered entertainment and news for a local television station. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Unconstituted Praxis

UnconstitutedPraxis PraxisUnconstituted MATTIN MATTIN UnconstitutedPraxis PraxisUnconstituted MATTIN MATTIN Unconstituted Praxis Unconstituted Unconstituted Praxis MATTIN MATTIN 'Noise & Capitalism - Exhibition as Concert' with Mattin is the first part of the project 'Scores' Unconstituted Praxis organised in collaboration by CAC Brétigny and Künstlherhaus Stuttgart. The second part with Beatrice Gibson: The Tiger's Mind will be presented from November 6th to December 31st in Stuttgart, Germany. www.kuenstlerhaus.de By Mattin 'Scores' is part of the project 'Thermostat, cooperations between 24 French and German art centres', With contributions by: an initiative from the Association of French centres d'art, d.c.a., and the Institut Français in Germany. addlimb, Billy Bao, Marcia Bassett, Loïc Blairon, Ray Brassier, Diego Chamy, Janine Eisenaecher, Barry Esson, The project is generously supported by the German Federal Cultural Foundation, the French Ministry Ludwig Fischer, Jean-Luc Guionnet, Michel Henritzi, Anthony Iles, Alessandro Keegan, Alexander Locascio, of Culture and Communication, Culturesfrance Seijiro Murayama, Loty Negarti, Jérôme Noetinger, Andrij Orel & Roman Pishchalov, Acapulco Rodriguez, as well as by the Plenipotentiary for the Franco-German Cultural Relations. Benedict Seymour, Julien Skrobek, Taumaturgia and Dan Warburton. is initiated by Edited by: Anthony Iles Cover Illustration: Epilogue by Howard Slater Metal Machine Illustrations: Metal Machine Theory I-V, questions by Mattin answers by With support of Ray Brassier, commissioned and published 2010-2011 by the experimental music magazine Revue et Corrigée. Drunkdriver concert photographs: Drunkdriver/Mattin live at Silent Bar, Queens 3 January 2009 Olivier Léonhardt, Président de la Communauté d'agglomération du Val d'Orge/ by Tina De Broux. President of the community of agglomeration Val d’Orge Patrick Bardon, Vice-Président de la Communauté d'agglomération du Val d'Orge/ Noise & Capitalism - exhibition as concert documentation: photographs by Steeve Beckouet. -

GOIN-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf

Copyright by Keara Kaye Goin 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Keara Kaye Goin Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Dominican Identity in Flux: Media Consumption, Negotiation, and Afro-Caribbean Subjectivity in the U.S. Committee: Mary Beltrán, Supervisor Maria Franklin Shanti Kumar Janet Staiger Joseph Straubhaar Dominican Identity in Flux: Media Consumption, Negotiation, and Afro- Caribbean Subjectivity in the U.S. by Keara Kaye Goin, BA, MA Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Acknowledgements There are many people I would like to thank who have been instrumental and provided unwavering support throughout the five year process that has culminated in this dissertation. I would first like to thank Mary Beltrán for not only serving as my dissertation chair but also my advisor and champion throughout my Ph.D. Thank you for reading countless drafts of papers, articles, and chapters. I know not all of them were exceptional and without you I would not have been able to accomplish half of what I was able to over our time together. Thank you for listening to me vent, giving me direction for my degree and academic future, and always being in my corner. Words cannot even begin to express the level of gratitude I have for you and all you have done for me. I would also like to thank my committee members, Maria Franklin, Shanti Kumar, Janet Staiger, and Joseph Straubhaar. -

I Concerti Dell'arena E Le Schede Degli Artisti

I CONCERTI DELL’ARENA E LE SCHEDE DEGLI ARTISTI (8 giugno) - ARENA Issac Delgado Issac Delgado è una delle icone della salsa mondiale. Figlio d’arte, sua madre - Lina Ramirez era attrice, ballerina e cantante - Issac è nato nel 1962 a Marianao, il popolare quartiere de La Havana. Ha registrato decine di album e vanta anche due cd pubblicati con la mitica etichetta RMM: il suo nome è ormai un punto di riferimento per i salseri di tutto il mondo. La sua carriera professionale è iniziata nel 1983 come componente dell’orchestra di Pacho Alonso. Nel 1988 è cantante solista di NG La Banda. Il suo primo gruppo risale al 1991. Da qualche anno vive a Miami con la sua famiglia. Innumerevoli i grandi successi, sopra tutti “La Vida Es Un Carnaval” incisa nel 1999 e che ancora oggi è la versione più conosciuta di questa canzone nel mondo. Issac Delgado ha una particolare ammirazione per l’Italia. E’ uno dei Paesi dove ha eseguito più concerti e questo suo amore lo ha dichiarato realizzando la versione salsa – cantata in italiano – di “Quando”, uno dei maggiori successi di Pino Daniele. (9 giugno) - ARENA Rodry-Go Rodrigo Rodriguez Puerta, conosciuto come Rodry-Go è un artista energetico, carismatico e a tratti romantico. Ma, soprattutto, è il fondatore di un nuovo genere musicale: il reggaelove. Colombiano di Cartagena, ha fatto parte, come cantante e percussionista, del gruppo Mercadonegro con centinaia di concerti internazionali al suo attivo. Nel 2001 è stato al “Pavarotti & Friends” con la leggendaria regina della salsa, Celia Cruz; ha suonato con star del calibro di Cheo Feliciano, Josè Aalberto “El Canario”, Richie Ray, Tito Nieves, Ray Sepulveda, Albita Rodriguez, Dave Valentin, Chico Freeman, Giovanni Hidalgo, Alfredo De La Fe, Los Hermanos Moreno, e molte altre stelle del mondo Strategie di Comunicazione Daniela Esposito Vittorio Morelli [email protected] Pag. -

Imperio Llamado Paris Un

FUNCIÓN Foto: Reuters Bar Refaeli pagará al fisco La israelí Bar Refaeli de- berá pagar una multa de EXCELSIOR | LUNES 14 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 2019 1.5 millones de dólares, además de 10 millones al fisco de su país por evasión fiscal. El tribunal condenó a la modelo a nueve meses de servicio comunitario y a su ma- Un dre, Zipi, a 16 meses de prisión. La mamá de la mode- lo comenzará a cumplir imperio su tiempo en prisión la semana próxima. La de- fensa de Refaeli intentó demostrar que no había evadido intencionalmen- llamado te el pago de impuestos, sin embargo, la fiscalía la acusó de dar informa- ción fiscal incorrecta. — De la Redacción Paris La empresaria estrena hoy un documental en el que se aleja del glamour y lujo que la han caracterizado Fotos: Cortesía YouTube POR RODOLFO MONROY M. Lo que la llevo a crear atención a las cosas nega- ¿QUÉ HA HECHO estaba lista para ese tipo de [email protected] This is Paris, explica, era tivas, me enfoco en lo po- relación. “No me conocía y mostrar una mujer empre- sitivo. La vida es muy corta DURANTE EL no me había permitido abrir Paris Hilton es empresaria, sarial y el imperio que ha como para preocuparse por AISLAMIENTO? mi corazón.” socialité, modelo, DJ, actriz, construido. “Estoy muy or- eso”, dice tajante. Están juntos desde el reina de los reality shows, gullosa de eso. Quería que Por ello trata de ser una Paris comparte que ha hecho Día de Acción de Gracias popularizó las selfies y va- el mundo pudiera ver mi buena influencia con sus trabajo de caridad para niños, y responsabiliza al desti- rias cosas más, pero con el verdadero ‘yo’. -

1 Hip Hop Latinidades: More Than Just Rapping in Spanish 2

contents Foreword: A Little Hip Hop History from the Bronx and Beyond ix MARK D. NAISON Acknowledgments xiii Part I Undefining Hip Hop Latinidades 1 Hip Hop Latinidades: More Than Just Rapping in Spanish 3 MELISSA CASTILLO- GARSOW and JASON NICHOLS 2 Borderland Hip Hop Rhetoric: Identity and Counterhegemony 17 ROBERT TINAJERO 3 ¡Ya basta con Latino!: The Re-Indigenization and Re-Africanization of Hip Hop 41 PANCHO McFARLAND and JARED A. BALL Part II Whose Black Music?: Afro- Latinidades and African Legacies in Latin American and Latino Hip Hop 4 From Panama to the Bay: Los Rakas’s Expressions of Afrolatinidad 63 PETRA R. RIVERA- RIDEAU 5 Bandoleros: The Black Spiritual Identities of Tego Calderon and Don Omar 80 JASON NICHOLS 6 “Te llevaste mi oro”: ChocQuibTown and Afro- Colombian Cultural Memory 90 CHRISTOPHER DENNIS 7 Now Let’s Shake to This: Viral Power and Flow from Harlem to São Paulo 108 HONEY CRAWFORD v vi • CONTENTS Part III Chicano? Mexican?: On the Borderlands of Mexican and Mexican American Hip Hop 8 Collective Amnesia 125 BOCAFLOJA 9 “Yo soy Hip Hop”: Transnationalism and Authenticity in Mexican New York 133 MELISSA CASTILLO- GARSOW 10 Graffiti and Rap on Mexico’s Northern Border: Observing Two Youth Practices— Transgressions or Reproductions of Social Order? 153 LISSET ANAHÍ JIMÉNEZ ESTUDILLO TRANSLATED BY JANELLE GONDAR 11 Somos pocos pero somos locos: Chicano Hip Hop Finds a Small but Captive Audience in Taipei 172 DANIEL D. ZARAZUA Part IV Somos Mujeres, Somos Hip Hop 12 Chicana Hip Hop: Expanding Knowledge in the L.A. Barrio 183 DIANA CAROLINA PELÁEZ RODRÍGUEZ TRANSLATED BY ADRIANA ONITA 13 Daring to Be “Mujeres Libres, Lindas, Locas”: An Interview with the Ladies Destroying Crew of Nicaragua and Costa Rica 203 JESSICA N.