Chapter III Affected Environment/Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW OCTOBER 1961 Death of General Lyon, Battle of Wilson's Creek Published Quarte e State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1959-1962 E. L. DALE, Carthage, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President WILLIAM L. BKADSHAW, Columbia, Second Vice President GEORGE W. SOMERVILLE, Chillicothe, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C. TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Secretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director. Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City L. M. WHITE, Mexico G. L. ZWICK. St Joseph Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1961 WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED 0. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1962 F C. BARNHILL, Marshall *RALPH P. JOHNSON, Osceola FRANK P. BRIGGS Macon ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. Louis HENRY A. BUNDSCHU, Independence FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia W. C. HEWITT, Shelbyville ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville Term Expires at Annual Meeting. 1963 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. -

The Janus-Faced Dilemma of Rock Art Heritage

The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon To cite this version: Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Taylor & Francis, In press, 10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329. hal-03078965 HAL Id: hal-03078965 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03078965 Submitted on 21 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Duval Mélanie, Gauchon Christophe, 2021. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329 Authors: Mélanie Duval and Christophe Gauchon Mélanie Duval: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France; * Rock Art Research Institute GAES, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Christophe Gauchon: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France. -

Glass Buttes, Oregon: 14,000 Years of Continuous Use (From a Presentation by Daniel O

“If I would study my old, lost art, let us say, I must make myself the artisan of it…” Frank Lukes, Editor Volume 31, Number 1 3809 Broadview Road, West Lafayette, IN January 2018 Website: www.worldatlatl.org Glass Buttes, Oregon: 14,000 Years of Continuous Use (from a presentation by Daniel O. Stueber) The article below is a summary by Anita Lukes of a presentation given by Daniel O. Stueber at the 2017 WAA Annual Meeting at Husum, Washington. His complete article with references can be downloaded for free at academia.edu and is as follows: Stueber, D.O. and Skinner, C.E., 2015, Glass Buttes, Oregon: 14,000 Year of Continuous Use In Toolstone Geography of the Pacific Northwest, Edited by Terry L. Ozbun and Ron L. Adams, pp 193-207. Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser For more than 14,000 years Glass Buttes, one of the largest obsidian sources in Oregon, has been a source of high quality toolstone for Native American flintknappers. Glass Buttes’ obsidian is of high quality, abundant, and in many colors. The colors include translucent and banded black, red, mahog- any, gold sheen, silver sheen, gray-green banded, rainbow, and banded or mottled multi-color combinations. It is found in large blocks or boulders, some weighing more than 100 pounds. Figure 1 shows many of these Oregon obsidian source sites. Because of the quality of Glass Buttes obsidian, it has been prized among Native American and First Nation people of North America. Obsidian from this source contin- ues to be coveted by present-day knappers. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee

From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Miller, Darcy Shane Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 09:33:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/320030 From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee by Darcy Shane Miller __________________________ Copyright © Darcy Shane Miller 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Darcy Shane Miller, titled From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Vance T. Holliday _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Steven L. Kuhn _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Mary C. Stiner _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) David G. Anderson Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Wege Zur Musik

The beginnings 40,000 years ago Homo sapiens journeyed up the River Danube in small groups. On the southern edge of the Swabian Alb, in the tundra north of the glacial Alpine foothills, the fami- lies found good living conditions: a wide offering of edible berries, roots and herbs as well as herds of reindeer and wild horses. In the valleys along the rivers they found karst caves which offered protection in the long and bleak winters. Here they made figures of animals and hu-mans, ornaments of pearls and musical instruments. The archaeological finds in some of these caves are so significant that the sites were declared by UNESCO in 2017 as ‘World Heritage Sites of Earliest Ice-age Art’. Since 1993 I have been performing concerts in such caves on archaic musical instruments. Since 2002 I have been joined by the percussion group ‘Banda Maracatu’. Ever since prehis- toric times flutes and drums have formed a perfect musical partnership. It was therefore natu- ral to invite along Gabriele Dalferth who not only made all of the ice-age flutes used in this recording but also masters them. The archaeology of music When looking back on the history of mankind, the period over which music has been docu- mented is a mere flash in time. Prior to that the nature of music was such that once it had fainted away it had disappeared forever. That is the situation for music archaeologists: The music of ice-age hunters and gatherers has gone for all time and cannot be rediscovered. Some musical instruments however have survived for a long time. -

Plains Anthropologist Author Index

Author Index AUTHOR INDEX Aaberg, Stephen A. (see Shelley, Phillip H. and George A. Agogino) 1983 Plant Gathering as a Settlement Determinant at the Pilgrim Stone Circle Site. In: Memoir 19. Vol. 28, No. (see Smith, Calvin, John Runyon, and George A. Agogino) 102, pp. 279-303. (see Smith, Shirley and George A. Agogino) Abbott, James T. Agogino, George A. and Al Parrish 1988 A Re-Evaluation of Boulderflow as a Relative Dating 1971 The Fowler-Parrish Site: A Folsom Campsite in Eastern Technique for Surficial Boulder Features. Vol. 33, No. Colorado. Vol. 16, No. 52, pp. 111-114. 119, pp. 113-118. Agogino, George A. and Eugene Galloway Abbott, Jane P. 1963 Osteology of the Four Bear Burials. Vol. 8, No. 19, pp. (see Martin, James E., Robert A. Alex, Lynn M. Alex, Jane P. 57-60. Abbott, Rachel C. Benton, and Louise F. Miller) 1965 The Sister’s Hill Site: A Hell Gap Site in North-Central Adams, Gary Wyoming. Vol. 10, No. 29, pp. 190-195. 1983 Tipi Rings at York Factory: An Archaeological- Ethnographic Interface. In: Memoir 19. Vol. 28, No. Agogino, George A. and Sally K. Sachs 102, pp. 7-15. 1960 Criticism of the Museum Orientation of Existing Antiquity Laws. Vol. 5, No. 9, pp. 31-35. Adovasio, James M. (see Frison, George C., James M. Adovasio, and Ronald C. Agogino, George A. and William Sweetland Carlisle) 1985 The Stolle Mammoth: A Possible Clovis Kill-Site. Vol. 30, No. 107, pp. 73-76. Adovasio, James M., R. L. Andrews, and C. S. Fowler 1982 Some Observations on the Putative Fremont Agogino, George A., David K. -

Assessing Relationships Between Human Adaptive Responses and Ecology Via Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling William E

Assessing relationships between human adaptive responses and ecology via eco-cultural niche modeling William E. Banks To cite this version: William E. Banks. Assessing relationships between human adaptive responses and ecology via eco- cultural niche modeling. Archaeology and Prehistory. Universite Bordeaux 1, 2013. hal-01840898 HAL Id: hal-01840898 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01840898 Submitted on 11 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thèse d'Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches Université de Bordeaux 1 William E. BANKS UMR 5199 PACEA – De la Préhistoire à l'Actuel : Culture, Environnement et Anthropologie Assessing Relationships between Human Adaptive Responses and Ecology via Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling Soutenue le 14 novembre 2013 devant un jury composé de: Michel CRUCIFIX, Chargé de Cours à l'Université catholique de Louvain, Belgique Francesco D'ERRICO, Directeur de Recherche au CRNS, Talence Jacques JAUBERT, Professeur à l'Université de Bordeaux 1, Talence Rémy PETIT, Directeur de Recherche à l'INRA, Cestas Pierre SEPULCHRE, Chargé de Recherche au CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette Jean-Denis VIGNE, Directeur de Recherche au CNRS, Paris Table of Contents Summary of Past Research Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College Version June 20, 2012

1 Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College version June 20, 2012 Introduction I began accumulating this bibliography around 1996, making notes for my own uses. Since I have access to some obscure articles, I thought it might be useful to put this information where others can get at it. Comments in brackets [ ] are my own comments, opinions, and critiques, and not everyone will agree with them. The thoroughness of the annotation varies depending on when I read the piece and what my interests were at the time. The many articles from atlatl newsletters describing contests and scores are not included. I try to find news media mentions of atlatls, but many have little useful info. There are a few peripheral items, relating to topics like the dating of the introduction of the bow, archery, primitive hunting, projectile points, and skeletal anatomy. Through the kindness of Lorenz Bruchert and Bill Tate, in 2008 I inherited the articles accumulated for Bruchert’s extensive atlatl bibliography (Bruchert 2000), and have been incorporating those I did not have in mine. Many previously hard to get articles are now available on the web - see for instance postings on the Atlatl Forum at the Paleoplanet webpage http://paleoplanet69529.yuku.com/forums/26/t/WAA-Links-References.html and on the World Atlatl Association pages at http://www.worldatlatl.org/ If I know about it, I will sometimes indicate such an electronic source as well as the original citation. The articles use a variety of measurements. Some useful conversions: 1”=2.54 -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Archeology Inventory Table of Contents

National Historic Landmarks--Archaeology Inventory Theresa E. Solury, 1999 Updated and Revised, 2003 Caridad de la Vega National Historic Landmarks-Archeology Inventory Table of Contents Review Methods and Processes Property Name ..........................................................1 Cultural Affiliation .......................................................1 Time Period .......................................................... 1-2 Property Type ...........................................................2 Significance .......................................................... 2-3 Theme ................................................................3 Restricted Address .......................................................3 Format Explanation .................................................... 3-4 Key to the Data Table ........................................................ 4-6 Data Set Alabama ...............................................................7 Alaska .............................................................. 7-9 Arizona ............................................................. 9-10 Arkansas ..............................................................10 California .............................................................11 Colorado ..............................................................11 Connecticut ........................................................ 11-12 District of Columbia ....................................................12 Florida ........................................................... -

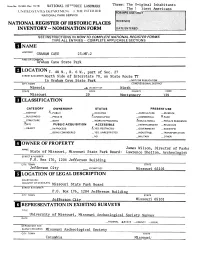

Hclassification

Form NO. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) NATIONAL HT prpORIC LANDMARK Theme: The Original Inhabitants The 1 liest Americans UNITED STATES DhPARTMEN l F THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY » NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC GRAHAM CAVE 23-MT-2 (LOCATION T 48 N> ^ R> 6 w<i part Qf Sec> 27 STREETS. NUMBER North Side of Interstate 70, on State Route TT in Graham Cave State Park _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Mineola _X VICINITY OF Ninth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Missouri 29 Mont gomerv 139 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT ^_PUBLIC _ OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE ^-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —STRUCTURE —BOTH __ WORKINPROGRE Sb .^EDUCATIONAL .—PRIVATE RESIDENCE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME James Wilson, Director of Parks State of Missouri, Missouri State Park Board: Lawrence Shelton, Archeologist STREET & NUMBER P.O. Box 176, 1204 Jefferson Building CITY. TOWN STATE Jefferson City Missouri 65101 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REG.STRY OF DEEDS, ETC STREET & NUMBER P.O. Box 176, 1204 Jefferson Building CITY, TOWN STATE Jefferson Citv Missouri 65101 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE University of Missouri, Missouri Archeological Society Survey DATE — FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR .SURVEYRECORDS Missouri Archeological Society CITY. TOWN STATE Columbia Missouri 1 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE _XGOOD _RUINS -X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR X—UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Graham Cave is located in a State Park near Mineola, Missouri, in the Loutre River Valley about 15 miles north of the Loutre's confluence with the Missouri River.