Anime and Identity: the Reception of Sailor Moon by Adolescent American Fans Darrah M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

水野亜美 Month You Will Find a New Article Demystifying Complex Translations Or the Name Is of Japanese-Origin; It Is Not Debunking Rumors Related to the Original Foreign

Japanese Focus Ever wanted to learn more about the Japanese behind the translations found for Sailor Moon? This article is for you! Each 水野亜美 month you will find a new article demystifying complex translations or The name is of Japanese-origin; it is not debunking rumors related to the original foreign. If it were foreign, it would almost Japanese found in Sailor Moon. Here you’ll certainly be written in katakana – more on find gratuitous use of linguistic vocabulary that later! related to the study of Japanese as a I propose that most of the meaning in her foreign language. I will do my best to name comes from her surname, and that if include footnotes for such vocabulary words people look too hard trying to find as much at the end of each editorial. meaning in "Ami", things will get muddied. As many of us are setting off on a new First, let’s break everything down kanji by academic journey with a new school year, I kanji. think it’s only fitting that we begin our segment with the soldier of wisdom: Sailor Mercury! Today I want to analyse a common 水 misconception about the meaning of Sailor Mercury’s civilian identity, “Mizuno Ami”. All This is the kanji for the word “mizu”, over the internet, you will find people saying meaning water. Sometimes, when paired that the proper translation for this with other kanji to make "compounds", it is character’s name is “Asian Beauty of pronounced as “sui” – but we’ll come back Water”, or “Secondary Beauty of Water”. -

Liste Des Jeux Game Boy 3 CHOUME NO TAMA

Liste des jeux Game Boy 3 CHOUME NO TAMA - TAMA AND FRIENDS - 3 CHOUME OBAKE PANIC!! 3-PUN YOSOU - UMABAN CLUB AA HARIMANADA AEROSTAR AFTER BURST AKAZUKIN CHACHA AMERICA OUDAN ULTRA QUIZ AMERICA OUDAN ULTRA QUIZ PART 2 AMERICA OUDAN ULTRA QUIZ PART 3 - CHAMPION TAIKAI AMERICA OUDAN ULTRA QUIZ PART 4 AMIDA ANIMAL BREEDER ANIMAL BREEDER 2 ANOTHER BIBLE AOKI DENSETSU SHOOT! ARCADE CLASSIC NO. 3 - GALAGA & GALAXIAN ARETHA ARETHA II ARETHA III ASMIK-KUN WORLD 2 ASTRO RABBY ATOMIC PUNK AYAKASHI NO SHIRO BAKENOU TV '94 BAKENOU V3 BAKUCHOU RETRIEVE MASTER BAKUCHOU RETSUDEN SHOU - HYPER FISHING BANISHING RACER BASS FISHING TATSUJIN TECHOU BATTLE ARENA TOSHINDEN BATTLE BULL BATTLE CITY BATTLE CRUSHER BATTLE DODGE BALL BATTLE OF KINGDOM BATTLE PING PONG BATTLE SPACE BIKKURI NEKKETSU SHIN KIROKU! - DOKODEMO KIN MEDAL BISHOUJO SENSHI SAILOR MOON BISHOUJO SENSHI SAILOR MOON R BLAST MASTER BOY BLOCK KUZUSHI GB BLODIA BOMBER MAN COLLECTION BOMBER MAN GB 3 BOOBY BOYS BOXING BUGS BUNNY COLLECTION BURNING PAPER CAPCOM QUIZ - HATENA NO DAIBOUKEN CAPTAIN TSUBASA J - ZENKOKU SEIHA E NO CHOUSEN CAPTAIN TSUBASA VS CARD GAME CASTELIAN CAVE NOIRE CHACHAMARU BOUKENKI 3 - ABYSS NO TOU CHACHAMARU PANIC CHALVO 55 - SUPER PUZZLE ACTION CHIBI MARUKO-CHAN - MARUKO DELUXE GEKIJOU CHIBI MARUKO-CHAN - OKOZUKAI DAISAKUSEN! CHIBI MARUKO-CHAN 2 - DELUXE MARUKO WORLD CHIBI MARUKO-CHAN 3 - MEZASE! GAME TAISHOU NO MAKI CHIBI MARUKO-CHAN 4 - KORE GA NIHON DA YO! OUJI-SAMA CHIKI CHIKI MACHINE MOU RACE CHIKI CHIKI TENGOKU CHIKYUU KAIHOU GUN ZAS CHOPLIFTER 2 CHOU MASHIN EIYUU DEN -

Why I Love Anime by Kaitlin Meaney I Figured I Would Take a Break

Why I love Anime By Kaitlin Meaney I figured I would take a break from writing about feelsy stuff to tell you about why I think anime is so awesome and that there is a lot to love about it. Also because I literally don’t have an anime to write about this week, at least nothing I’ve watched a whole series of yet. This is me taking a break this month. Anime has been a big part of my life ever since I was a child. My first exposures coming from Pokemon, Beyblade, Sailor Moon, Digimon, and Yu-Gi-Oh just to name a few. As I got older I found that the medium was a lot bigger than just the few I had seen in Saturday morning cartoons. In high school I was exposed to my first few subbed anime in the school anime club. I would say that I only truly realized my love for anime while in that club. Now I am an active member of the fandom watching anything that tickles my fancy. Anime is a much appreciated medium of television but it is vastly underrated. It’s regarded as one of the nerdiest thing right next to Dungeons and Dragons and/or video games. But there are some things about this medium that set it apart from the others. Something that makes it unique and creates the devoted fans that exist in abundance this day and age. I’ll be talking about what I personally love about anime and what makes it so cool in my eyes. -

Telly Was Our Buddy

p e r i s c o p e p e r i s c o p e C HRI “‘A Saiyan was show Flash Fax was something in our Z CHAN born in this place. He memories that can never be replaced. is called Son Goku!’” The locally produced children’s tel- the first line of lyrics evision show, running from 1989 to of the theme song 1999, was memorable for its songs. At TELLY immediately came that time, they were not always avail- to Isabella Wong’s able on CD albums. Pheonix Cham Ka- mind when talking ling, now 21, said she cut out the lyrics WAS OUR about Dragon Ball published in children magazines and Z. She said she was memorized them. That was “kid’s intel- so amazed by the ligence”, as she termed. BUDDY fiery hairstyle of Vince Lam was also a children’s song the Super Saiyans fan. As a small child, she was greatly (超級撒亞人). influenced by the meanings behind Freeza (����, the lyrics. One of the songs which The colossal collection of kid songs by Mr Oldkid Artificial Human touched her deeply was “The Story of No. 17 and 18, to Majin Buu (��人� Ah-Fa”, about the friendship between Tsubasa”, which is about the adven- 歐), the hero Son Goku and other char- a girl and a cat. ture of a Japanese soccer youth team, acters combat these evils through the “I couldn’t help crying whenever I reminds a lot of boys, including Mr 291-episode series. heard about the death of the cat at the Television was the buddy of those growing up in 90’s. -

Still Buffering 198: "Sailor Moon" (1992) Published February 6Th, 2020 Listen Here on Themcelroy.Family [Theme Music P

Still Buffering 198: "Sailor Moon" (1992) Published February 6th, 2020 Listen here on themcelroy.family [theme music plays] Rileigh: Hello, and welcome to Still Buffering: a cross-generational guide to the culture that made us. I am Rileigh Smirl. Sydnee: I'm Sydnee McElroy. Teylor: And I'm Teylor Smirl! Sydnee: So, lots of big events this past weekend. Rileigh: [laughs] Teylor: Yeah? Rileigh: Yeah. Superbowl. Sydnee: Yeah? Teylor: You say it like there's some—is there something else? Sydnee: Groundhog day. Teylor: Oh, oh right. Rileigh: Oh, right. Yes. Teylor: We're gettin'—so he saw his shadow, so that means spring's comin'? Rileigh: Yes. Sydnee: No, he didn't see his shadow, so— Teylor: Didn't see his shadow. Sydnee: —so spring is coming. Rileigh: But spring is coming. Sydnee: Yes. Teylor: Okay. Sydnee: That is— Rileigh: Apparently that never happens? Like, he always sees his shadow? Sydnee: Yes. Rileigh: So… big deal, guys. Teylor: You know that they—like, they claim it's the same groundhog since forever? Like, it's not. We know it's not, but they say it is? Sydnee: Right. Teylor: Like, it's like— Rileigh: [gasps] What? Sydnee: That's a weird thing to claim. Teylor: Like, the eternal groundhog. Rileigh: Wait… Teylor: Also, the guy that gets the— Sydnee: Did you think… Teylor: Yeah, he's not an eternal groundhog. Rileigh: What? Sydnee: Yeah. Rileigh: I thought— Sydnee: Groundhogs are mortal. Rileigh: But… oh. I thought he was special. Sydnee: [laughs quietly] Rileigh: [holding back laughter] 'Cause it's his day. -

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma De Puebla

BENEMÉRITA UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE PUEBLA INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y HUMANIDADES “ALFONSO VÉLEZ PLIEGO” MAESTRÍA EN SOCIOLOGÍA EXPERIENCIA Y CULTURA JAPONESA EN IMÁGENES HISTÓRICAS MERCANTILES DEL ANIME EN MÉXICO TESIS PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE MAESTRO EN SOCIOLOGÍA PRESENTA: LIC. ALAN EUGENIO GONZÁLEZ DIRECTOR: DR. FERNANDO T. MATAMOROS PONCE PUEBLA, PUE., DICIEMBRE 2020 1 Índice Portada……………………………………………………………………………………... 1 Agradecimientos………………………………………………............................................ 4 Introducción………………………………………………………………………………... 9 Capítulo I Revisión conceptual sobre las dimensiones culturales japonesas en la conformación de identidades………………………………………………………………………………. 17 1.1 La cultura y la vida cotidiana en una sociedad………………………………………. 18 1.2 Una sociedad dominada……………………………………………………………… 38 1.3 Impulsos y deseos de los sujetos en una sociedad…………………………………… 49 Capítulo II Una puerta al pasado: Lo japonés en México como antecedente participativo en la llegada del anime………………………………………………………………………... 57 2.1 Un encuentro, antes de un México. La misión Hasekura……………………………. 59 2.2 La comisión astronómica y las migraciones japonesas……………………………… 62 2.2.1 La comisión astronómica y sus consecuencias…………………………….. 62 2.2.2 Las migraciones japonesas………………………........................................ 67 2.3 La vida durante y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial………………………….. 82 2.4 La literatura japonesa………………………………………………………………... 93 2.5 El karate en México………………………………………………………………….. 96 2.5.1 Koichi Choda Watanabe y el Karate-do -

Naoko Takeuchi

Naoko Takeuchi After going to the post-recording parties, I realized that Sailor Moon has come to life! I mean they really exist - Bunny and her friends!! I felt like a goddess who created mankind. It was so exciting. “ — Sailor Moon, Volume 3 Biography Naoko Takeuchi is best known as the creator of Sailor Moon, and her forte is in writing girls’ romance manga. Manga is the Japanese” word for Quick Facts “comic,” but in English it means “Japanese comics.” Naoko Takeuchi was born to Ikuko and Kenji Takeuchi on March 15, 1967 in the city * Born in 1967 of Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan. She has one sibling: a younger brother named Shingo. Takeuchi loved drawing from a very young age, * Japanese so drawing comics came naturally to her. She was in the Astronomy manga (comic and Drawing clubs at her high school. At the age of eighteen, Takeuchi book) author debuted in the manga world while still in high school with the short story and song writer “Yume ja Nai no ne.” It received the 2nd Nakayoshi Comic Prize for * Creator of Newcomers. After high school, she attended Kyoritsu Yakka University. Sailor Moon While in the university, she published “Love Call.” “Love Call” received the Nakayoshi New Mangaka Award for new manga artists and was published in the September 1986 issue of the manga magazine Nakayo- shi Deluxe. Takeuchi graduated from Kyoritsu Yakka University with a degree in Chemistry specializing in ultrasound and medical electronics. Her senior thesis was entitled “Heightened Effects of Thrombolytic Ac- This page was researched by Em- tions Due to Ultrasound.” Takeuchi worked as a licensed pharmacist at ily Fox, Nadia Makousky, Amanda Polvi, and Taylor Sorensen for Keio Hospital after graduating. -

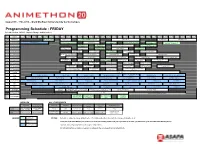

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/Changes in Thick Borders)

August 9th - 11th, 2013 -- Grant MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/changes in thick borders) Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM 12:00 AM GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess The Magic of BOOM! Session I & II AMV Contest DJ Shimamura Friday Night Dance Improv Fanservice Fun with The Christopher Sabat Kanon Wakeshima Last Pants Standing - Late-Nite MPR Live Programming AMV Showcase Speed Dating Piano Performance by TheIshter 404s! Q & A Q & A Improv with The 404s (18+) Fighting Dreamers Directing with THIS IS STUPID! Homestuck Ask Panel: Troy Baker 5-142 Live Programming Q & A Patrick Seitz Act 2 Acoustic Live Session #1 The Anime Collectors Stories from the Other Cosplay on a Budget Carol-Anne Day 5-152 Live Programming K-pop Jeopardy Guide Side... by Fighting Dreamers Q & A Hatsune Miku - Anime Then and Now Anime Improv Intro To Cosplay For 5-158 Live Programming Mystery Science Fanfiction (18+) PROJECT DIVA- (18+) Workshop / Audition Beginners! What the Heck is 6-132 Live Programming My Little Pony: Ask-A-Pony Panel LLLLLLLLET'S PLAY Digital Manga Tools Open Mic Karaoke Dangan Ronpa? 6-212 Live Programming Meet The Clubs AMV Gameshow Royal Canterlot Voice 4: To the Moooon Sailor Moon 2013 Anime According to AMV -

Exploring the Magical Girl Transformation Sequence with Flash Animation

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design 5-10-2014 Releasing The Power Within: Exploring The Magical Girl Transformation Sequence With Flash Animation Danielle Z. Yarbrough Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Yarbrough, Danielle Z., "Releasing The Power Within: Exploring The Magical Girl Transformation Sequence With Flash Animation." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELEASING THE POWER WITHIN: EXPLORING THE MAGICAL GIRL TRANSFORMATION SEQUENCE WITH FLASH ANIMATION by DANIELLE Z. YARBROUGH Under the Direction of Dr. Melanie Davenport ABSTRACT This studio-based thesis explores the universal theme of transformation within the Magical Girl genre of Animation. My research incorporates the viewing and analysis of Japanese animations and discusses the symbolism behind transformation sequences. In addition, this study discusses how this theme can be created using Flash software for animation and discusses its value as a teaching resource in the art classroom. INDEX WORDS: Adobe Flash, Tradigital Animation, Thematic Instruction, Magical Girl Genre, Transformation Sequence RELEASING THE POWER WITHIN: EXPLORING THE MAGICAL GIRL TRANSFORMATION SEQUENCE WITH FLASH ANIMATION by DANIELLE Z. YARBROUGH A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art Education In the College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University 2014 Copyright by Danielle Z. -

Neon Genesis Evangelion and Cardcaptor Sakura Voice Actress Megumi Ogata Launches Crowdfunding Projects to Produce Anime Song Co

Press Release Tokyo Otaku Mode Inc. May 17, 2017 Neon Genesis Evangelion and Cardcaptor Sakura Voice Actress Megumi Ogata Launches Crowdfunding Projects to Produce Anime Song Cover Album First project launched in Japan raises $100,000 in less than two hours Tokyo Otaku Mode Inc. (incorporated in Delaware, U.S.; representative: Tomohide Kamei; CEO: Naomitsu Kodaka; herein referred to as TOM) will launch an international crowdfunding project to support the production and release of voice actress and singer Megumi Ogata’s anime song cover album, “Animeg. 25th”. The crowdfunding project will be launched at 7:00 pm (PDT) on May 18 through TOM’s crowdfunding platform - Tokyo Mirai Mode (https://miraimode.com/projects/animeg25th) - that is directed towards fans residing outside of Japan. A promotional live stream featuring Megumi Ogata will be made through TOM’s Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/tokyootakumode/) 30 minutes before the crowdfunding project is launched. TOM will work together with CAMPFIRE - one of the largest crowdfunding platforms in Japan - that is managed by CAMPFIRE, Inc. (Headquarters: Shibuya Ward, Tokyo; President & CEO: Kazuma Ieiri) for this cover album project. The Japanese crowdfunding project launched first on May 12 through CAMPFIRE reached its target of ten million yen (approximately $90,000 USD) in just 90 minutes. The Japanese crowdfunding project is currently on its fourth day and has raised approximately twenty million yen. The international and Japanese crowdfunding projects will be launched to support the production and release of Megumi Ogata’s anime song cover album for her 25th voice actress debut anniversary, and also to provide the album to fans residing outside of Japan. -

Sailor Mars Meet Maroku

sailor mars meet maroku By GIRNESS Submitted: August 11, 2005 Updated: August 11, 2005 sailor mars and maroku meet during a battle then fall in love they start to go futher and futher into their relationship boy will sango be mad when she comes back =:) hope you like it Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/GIRNESS/18890/sailor-mars-meet-maroku Chapter 1 - sango leaves 2 Chapter 2 - sango leaves 15 1 - sango leaves Fanart Central A.whitelink { COLOR: #0000ff}A.whitelink:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.whitelink:visited { COLOR: #0000ff}A.BoxTitleLink { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:hover { COLOR: #465584; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:visited { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.normal { COLOR: blue}A.normal:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.normal:visited { COLOR: #000020}A { COLOR: #0000dd}A:hover { COLOR: #cc0000}A:visited { COLOR: #000020}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper { COLOR: #ff0000}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:hover { COLOR: #ffaaaa}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:visited { COLOR: #cc0000}.BoxTitleColor { COLOR: #000000} picture name Description Keywords All Anime/Manga (0)Books (258)Cartoons (428)Comics (555)Fantasy (474)Furries (0)Games (64)Misc (176)Movies (435)Original (0)Paintings (197)Real People (752)Tutorials (0)TV (169) Add Story Title: Description: Keywords: Category: Anime/Manga +.hack // Legend of Twilight's Bracelet +Aura +Balmung +Crossovers +Hotaru +Komiyan III +Mireille +Original .hack Characters +Reina +Reki +Shugo +.hack // Sign +Mimiru -

![[Company Name]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0400/company-name-960400.webp)

[Company Name]

Banpresto Collector Items Product Catalog February 2015 Product Catalog February 2015 1. Purchase Orders are due October 8, 2014 2. Product will be shipped February 1, 2015 • There will be no opportunity for reorders. All orders are one and done. • Orders must be placed in case pack increments. • Every month Bandai will introduce a new line of products. For example, next month’s catalog will feature items available March 2015. Product Image Distribution Guidelines You may begin selling to your direct accounts and consumers immediately. Images are available upon request. • This 6.3” figure of Sailor Moon (Rei Hino in Japan) is part of the “Girls Memory” series of th 6.3” figures celebrating the 20 anniversary of Sailor Moon! • Collect and display with Sailor Moon & Sailor Mercury!! (Launch in January 2015) • Base included “Sailor Moon Crystal” airs on neoalley.com every 1st & 3rd Saturday of the month, the same time as Japan! ©Naoko Takeuchi / PNP, TOEI ANIMATION Product Ord # #31626 Name “Girls Memory” Figure Series – SAILOR MARS Assortment Info Age Grade 8+ Item # Item UPC Item Description Unit / Case Cost $16.00 31627 0-45557-31627-3 SAILOR MARS 32 SRP $28.00 Packaging Master Carton H W D H W D ITF-14 7.1 4.7 3.5 18.7 27.0 13.4 0-0045557-31626-6 Type Closed Box Weight 18.9 Total Case Pack 32 2” “Sailor Moon Crystal” airs on neoalley.com every 1st & 3rd Saturday of the month, the same time as Japan! ©Naoko Takeuchi / PNP, TOEI ANIMATION Product Ord # #31628 Name SAILOR MOON Collectable Figure for Girls Vol.