Legacy Trees of Ernest Henry Wilson and John George Jack in Nikko, Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ashikagasanonoodlehigh

ASHIKAGASANONOODLEHIGHWAY ASHIKAGA-CITY,SANO-CITY,TOCHIGI-CITY LOCAL NOODLE GUIDE MAP SOBA (buckwheat noodles) (buckwheat From TOKYO to ASHIKAGA in 70 MINUTES Access.1 (by Train) 蕎麦 Haneda Airport ▶ Ashikagashi Haneda Airport ---(Keihin Kyuko Line)--- Asakusa --- (Tobu Line Limited Express Ryomo)--- Ashikagashi Access.2 (by Train) Narita Airport ▶ Ashikagashi Narita Airport ---(Keisei Line Limited Express)--- Nippori --- (JR Jyoban Line)--- Kita-Senjyu ---(Tobu Line Ltdexpress Ryomo) --- Ashikagashi Access.3 (by Train) Tokyo station ▶ Ashikagashi Tokyo station ---(JR Keihin Tohoku Line )--- Ueno --- (Tokyo Metro Hibiya Line)--- Kita-Senjyu --- (Tobu Line Ltdexpress Ryomo)--- Ashikagashi Access.4 (by Car) Tokyo(Asakusa) ▶ Ashikaga Eat traditional Japanese soba at ancient city Ashikaga. Tokyo(Asakusa) --- Syuto Expressway(Central Circular Route/ Kawaguchi Route)--- Urawa toll Boot --- Tohoku Expressway--- Issaan is located in the town of Ashikaga, Tochigi Prefecture. the dishes they produce. When coming to Ashikaga people will be Ashikaga has many different temples and shrines that are considered surprised by the taste of pure Japanese soba as it is seasoned and Iwafune Junction --- Kita-Senjyu --- Kitakanto expressway --- as National treasures. When visiting Ahikaga I recommend seeing served according to the people’ s taste. In addition to the refreshing Ashikaga Interchange --- Ashikaga Bannaji Temple and the remains of Ashikaga School. If you’ re taste of handmade buckwheat, fried tempura is complemented. feeling hungry I highly recommend a place called “Issaan” . Issaan Fragrant tempura fried shrimp and seasonal vegetables will make restaurant is built in Japanese style, which gives it relaxing and everyone eating smile. Many people associate Japan with sushi, or beautiful features. The rooms also have tatami flooring and the view tempra, but I think everyone should try soba if they are in Japan. -

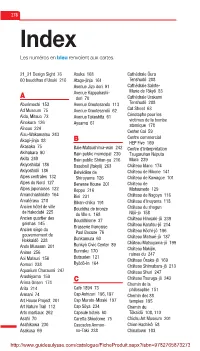

Index Du Guide

278 Index Les numéros en bleu renvoient aux cartes. 21_21 Design Sight 76 Asuka 168 Cathédrale Ôura 60 bouddhas d’Usuki 216 Atago-jinja 161 Tenshudô 208 Avenue Jizo dori 91 Cathédrale Sainte- Avenue Kappabashi- Marie de Tôkyô 83 A dori 70 Cathédrale Urakami Aburimochi 153 Avenue Omotesando 113 Tenshudô 208 Ad Museum 75 Avenue Omotesandô 62 Cat Street 63 Aida, Mitsuo 73 Avenue Takeshita 61 Cénotaphe pour les victimes de la bombe Ainokura 126 Ayoama 61 atomique 178 Aïnous 224 Center Gai 59 Aizu-Wakamatsu 243 B Centre commercial Akagi-jinja 88 HEP Five 169 Akasaka 75 Baie Matsushima-wan 242 Centre d’interprétation Akihabara 90 Bain public municipal 230 Tsugaruhan Néputa Akita 240 Bain public Shitan-yu 216 Mura 239 Akiyoshidai 186 Baseball (Yakyû) 263 Château blanc 174 Akiyoshidô 186 Belvédère de Château de Hikone 141 Alpes centrales 132 Shiroyama 126 Château de Kawagoe 101 Alpes du Nord 127 Benesse House 201 Château de Alpes japonaises 122 Beppu 216 Matsumoto 129 Amanohashidate 164 Biei 231 Château de Nagoya 116 Amatérasu 218 Bikan-chiku 191 Château d’Inuyama 118 Ancien hôtel de ville Bouddha de bronze Château du shogun de Hakodaté 225 du VIIe s. 168 Nijô-jo 158 Ancien quartier des Bouddhisme 37 Château Hirosaki-jô 239 geishas 145 Brasserie française Château Karatsu-jô 214 Ancien siège du Paul Bocuse 76 Château Kôchi-jô 196 gouvernement de Bunkamura 60 Château Matsué-jô 187 Hokkaidô 228 Château Matsuyama-jô 199 Ando Museum 201 Bunkyô Civic Center 89 Bunraku 170 Château Nakijin, Anime 256 ruines du 247 Butsuden 121 Aoi Matsuri 156 Château -

Description of Fences

Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Description of Fences フェンスの説明 / Description des obstacles Fence 1 – RIO 2016 EQUO JUMPINDV----------QUAL000100--_03B 1 Report Created TUE 3 AUG 2021 17:30 Page 1/14 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Fence 2 – Tokyo Skyline Tōkyō Sukai Tsurī o 東京スカイツリ Sumida District, Tokyo The new Tokyo skyline has been eclipsed by the Sky Tree, the new communications tower in Tokyo, which is also the highest structure in all of Japan at 634 metres, and the highest communications tower in the world. The design of the superstructure is based on the following three concepts: . Fusion of futuristic design and traditional beauty of Japan, . Catalyst for revitalization of the city, . Contribution to disaster prevention “Safety and Security”. … combining a futuristic and innovating design with the traditional Japanese beauty, catalysing a revival of this part of the city and resistant to different natural disasters. The tower even resisted the 2011 earthquake that occurred in Tahoku, despite not being finished and its great height. EQUO JUMPINDV----------QUAL000100--_03B 1 Report Created TUE 3 AUG 2021 17:30 Page 2/14 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Fence 3 – Gold Repaired Broken Pottery Kintsugi, “the golden splice” The beauty of the scars of life. The “kintsugi” is a centenary-old technique used in Japan which dates of the second half of the 15th century. -

NIKKO GUIDE MAP for MUSLIMS

A B C D E English Inset : Please use the convenient NIKKO Central Nikko Tourist Center at Tobu Nikko Station! Nikkō-toshogu GUIDE MAP Shrine Ryuo Valley / 93 Located inside 日光東照宮 Nikkō Tobu Nikko Station! Futarasan Shrine 01 111 龍王峡 for MUSLIMS 日光二荒山神社 Nikko is a place, where you can meet new people and English-speaking sta are Ryuokyo Sta. the healing power of nature while enjoying its history and culture. 14 85 always available! 龍王峡駅 1 81 92 2hour NIKKO HALAL TOKYO 84 Rinno-ji Temple on Mt. Nikkō Prayer Space History Muslim-Friendly Entertainment OSAKA 日光山輪王寺 09 TN & Nature Restaurant/Cafe & Activities 83 82 Shin-fujiwara Sta. / 新藤原駅 58 10 08 91 86 Shinkyo 07 神橋 11 06 02 Kinugawa Kōen Sta. 12 Please use the convenient 10 07 07 鬼怒川公園駅 06 106 Tourist Center TN 10 Tōbu-nikkō Sta. 57 TN 05 05 東武日光駅 25 at Kinugawa-Onsen Station! 90 1 We provide tourist 04 information. Located inside JR Nikkō Sta. 03 04 Luggage-free sightseeing Kinugawa-Onsen Station! For more detailed information JR 日光駅 2 service about Nikko, check here! You can purchase return bus ticket 01 04 02 (free pass) at value 3 Multi-lingual ticket machine price or theme 06 11 01 ¡Credit cards accepted! ¢ N1 park advance TN www.tobujapantrip.com/features/muslim/ ・ Nikkō Toshogu Shirine ticket, and arrange 56 04 04 Rinnoji Temple on Mt.Nikkō optional tours and/or ・ 105 Kinugawa- ・ Tobu Bus Free Pass accommodation. onsen Sta. 2 鬼怒川温泉駅 Bus routes from Tōbu-nikkō Sta. TN 01 12 2A Y For Yumoto onsen (via Chūzenji onsen) Tobu World Square Sta. -

Description of Fences

Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Description of Fences フェンスの説明 / Description des obstacles Fence 1 – The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Hokusai. Author: (Katsushika Hokusai) Original Title: (Kanagawa-oki nami ura) Year: 1829 – 1832 Base/stand: Colour-engraved upon a wooden block. Japanese ukiyo-e master. The Great Wave is the most recognized piece by Japanese painter Katsushika Hokusai, who specializes in ukiyo-e. Published between 1830 and 1833 during the Edo period, it forms part of the collection “Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji”, even though Mount Fuji is the smallest element. The wave references the relentless force of nature, the sea, and the importance this event has in Japan’s economy and its cultural development, given the country is formed by 4 islands. EQUO JUMPTEAM----------FNL-0002RR--_03B 1 Report Created SAT 7 AUG 2021 16 :45 Page 1/7 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Fence 4 – Mascot of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics Japanese illustrator Ryo Taniguchi. Manga and gamer references are seen, in representation of the Japanese contemporary visual culture and with a character design inspired by the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games’ Logo. The pair of futuristic characters combine tradition and innovation. The name of the Olympics mascot, Miraitowa, fuses the Japanese words for future and eternity. Someity, the Paralympics mascot, is derived from Somei-yoshino, a type of cherry blossom, cherry blossom variety "Someiyoshino" and is a play on words with the English phrase “So mighty”. -

Case Study of Anatomy, Physical and Mechanical Properties of the Sapwood and Heartwood of Random Tree Platycladus Orientalis (L.) Franco from South-Eastern Poland

Article Case Study of Anatomy, Physical and Mechanical Properties of the Sapwood and Heartwood of Random Tree Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco from South-Eastern Poland Agnieszka Laskowska * , Karolina Majewska, Paweł Kozakiewicz , Mariusz Mami ´nskiand Grzegorz Bryk The Institute of Wood Sciences and Furniture, 159 Nowoursynowska St., 02-776 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (K.M.); [email protected] (P.K.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (G.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Oriental arborvitae is not fully characterized in terms of its microscopic structure or physical or mechanical properties. Moreover, there is a lot of contradictory information in the literature about oriental arborvitae, especially in terms of microscopic structure. Therefore, the sapwood (S) and heartwood (H) of Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco from Central Europe were subjected to examinations. The presence of helical thickenings was found in earlywood tracheids (E). Latewood tracheids (L) were characterized by a similar thickness of radial and tangential walls and a similar diameter in the tangential direction in the sapwood and heartwood zones. In the case of earlywood tracheids, such a similarity was found only in the thickness of the tangential walls. The volume swelling (VS) of sapwood and heartwood after reaching maximum moisture content (MMC) was 12.8% (±0.5%) and 11.2% (±0.5%), respectively. The average velocity of ultrasonic Citation: Laskowska, A.; Majewska, waves along the fibers (υ) for a frequency of 40 kHz was about 6% lower in the heartwood zone K.; Kozakiewicz, P.; Mami´nski,M.; than in the sapwood zone. The dynamic modulus of elasticity (MOED) was about 8% lower in the Bryk, G. -

WRA Species Report

Family: Cupressaceae Taxon: Thuja x 'Green Giant' Synonym: Thuja plicata J. Donn ex D. Don x Thuja stan Common Name: 'Green Giant' Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: Chuck Chimera Designation: L Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: Chuck Chimera WRA Score -14 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 y 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 n 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 n 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- Low substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- Low high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 n 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 ? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see n Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic y=1, n=0 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host -

Feelin' Casual! Feelin' Casual!

Feelin’ casual! Feelin’ casual! to SENDAI to YAMAGATA NIIGATA Very close to Aizukougen Mt. Chausu NIIGATA TOKYO . Very convenient I.C. Tohoku Expressway Only 50minutes by to NIKKO and Nasu Nasu FUKUSHIMA other locations... I.C. SHINKANSEN. JR Tohoku Line(Utsunomiya Line) Banetsu Utsunomiya is Kuroiso Expressway FUKUSHIMA AIR PORT Yunishigawa KORIYAMA your gateway to Tochigi JCT. Yagan tetsudo Line Shiobara Nasu Nishinasuno- shiobara shiobara I.C. Nishi- nasuno Tohoku Shinkansen- Kawaji Kurobane TOBU Utsunomiya Line Okukinu Kawamata 3 UTSUNO- UTSUNOMIYA MIYA I.C. Whole line opening Mt. Nantai Kinugawa Jyoutsu Shinkansen Line to traffic schedule in March,2011 Nikko KANUMA Tobu Bato I.C. Utsunomiya UTSUNOMIYA 2 to NAGANO TOCHIGI Line TOCHIGI Imaichi TSUGA Tohoku Shinkansen Line TAKA- JCT. MIBU USTUNOMIYA 6 SAKI KAMINOKAWA 1 Nagono JCT. IWAFUNE I.C. 1 Utsunomiya → Nikko JCT. Kitakanto I.C. Karasu Shinkansen Expressway yama Line HITACHI Ashio NAKAMINATO JR Nikko Line Utsunomiya Tohoku Shinkansen- I.C. I.C. TAKASAKI SHIN- Utsunomiya Line TOCHIGI Kanuma Utsunomiya Tobu Nikko Line IBARAKI AIR PORT Tobu Motegi KAWAGUCHI Nikko, where both Japanese and international travelers visit, is Utsuno- 5 JCT. miya MISATO OMIYA an international sightseeing spot with many exciting spots to TOCHIGI I.C. see. From Utsunomiya, you can enjoy passing through Cherry Tokyo blossom tunnels or a row of cedar trees on Nikko Highway. Utsunomiya Mashiko Tochigi Kaminokawa NERIMA Metropolitan Mibu I.C. Moka I.C. Expressway Tsuga I.C. SAPPORO JCT. Moka Kitakanto Expressway UENO Nishikiryu I.C. ASAKUSA JR Ryomo Line Tochigi TOKYO Iwafune I.C. Kasama 2 Utsunomiya → Kinugawa Kitakanto Expressway JCT. -

Combatting the Urban Heat Island Effect

Combatting the Urban Heat Island Effect: What Trees Are Suitable for Atlanta’s Current and Future Climate? An Applied Research Paper Written by: Anna Baggett Supervised by: Dr. Brian Stone Spring 2019 Acknowledgements This report was prepared for Georgia Tech’s School of City and Regional Planning as a part of its applied research paper requirement. This paper would not have been possible without the support of Dr. Brian Stone who supervised its writing. The author would also like to thank Alex Beasley and Mike McCord at Trees Atlanta for generously offering tree species lists. Cover photo credit: 1460daysofgeorgia.wordpress.com Back cover photo credit: ATLnature Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................................2 Trees and the UHI Effect ............................................................................................2 Shifting Plant Hardiness Zones .........................................................................3 Future Climates and Tree Planting ..................................................................4 Gaps in Current Literature ......................................................................................4 METHODS.......................................................................................................................................5 Hardiness Zones ..............................................................................................................5 -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Mao et al. 10.1073/pnas.1114319109 SI Text BEAST Analyses. In addition to a BEAST analysis that used uniform Selection of Fossil Taxa and Their Phylogenetic Positions. The in- prior distributions for all calibrations (run 1; 144-taxon dataset, tegration of fossil calibrations is the most critical step in molecular calibrations as in Table S4), we performed eight additional dating (1, 2). We only used the fossil taxa with ovulate cones that analyses to explore factors affecting estimates of divergence could be assigned unambiguously to the extant groups (Table S4). time (Fig. S3). The exact phylogenetic position of fossils used to calibrate the First, to test the effect of calibration point P, which is close to molecular clocks was determined using the total-evidence analy- the root node and is the only functional hard maximum constraint ses (following refs. 3−5). Cordaixylon iowensis was not included in in BEAST runs using uniform priors, we carried out three runs the analyses because its assignment to the crown Acrogymno- with calibrations A through O (Table S4), and calibration P set to spermae already is supported by previous cladistic analyses (also [306.2, 351.7] (run 2), [306.2, 336.5] (run 3), and [306.2, 321.4] using the total-evidence approach) (6). Two data matrices were (run 4). The age estimates obtained in runs 2, 3, and 4 largely compiled. Matrix A comprised Ginkgo biloba, 12 living repre- overlapped with those from run 1 (Fig. S3). Second, we carried out two runs with different subsets of sentatives from each conifer family, and three fossils taxa related fi to Pinaceae and Araucariaceae (16 taxa in total; Fig. -

Conifer Quarterly

cover 10/11/04 3:58 PM Page cov1 Conifer Quarterly Vol. 21 No. 4 Fall 2004 cover 10/11/04 3:58 PM Page cov2 An exhibit at the New York Botanical Gardens, coinciding with the re-opening of their refurbished conifer collection, runs from October 30, 2004, through January 30, 2005. Read more on page 27. NYBG of Tom Cox Courtesy Right: Thuja occidentalis ‘Emerald’ at the Cox Arboretum in Georgia. Below: Thuja occidentalis ‘Golden Tuffet,’ also at the Cox Arboretum. Turn to page 6 to read about more arborvitae cultivars. Cox Tom Inside-5.qxp 10/6/04 3:53 PM Page 1 The Conifer Quarterly is the publication of The Conifer Society Contents Featured conifer genus: Thuja (arborvitae) 6 Arborvitae in Your Ornamental Conifer Garden Tom Cox 12 Improving the Tree of Life: Thuja occidentalis From Seed Clark West 17 Thuya Garden: An Oasis Along Maine’s Rocky Coast Anne Brennan 20 Reader Recommendations More features 26 Grand Re-Opening of Benenson Ornamental Conifers from the New York Botanical Garden 32 Marvin Snyder Recognized for Dedicated Support 33 Award for Development in the Field of Conifers Presented to J.R.P. van Hoey Smith 38 All Eyes on Ohio Bill Barger 42 Dutch Conifer Society Tours West Coast Don Howse Conifer Society voices 2 President’s Message 4 Editor’s Memo 30 Conifer Puzzle Page 36 Iseli Grant Recipient Announced 37 Conifers in the News 46 News from our Regions Cover photo: Thuja occidentalis ‘Gold Drop’ in the garden of Charlene and Wade Harris. See the article beginning on page 12 to read more about this cultivar.