Scott Bradley's Music for MGM's Cartoons Helen Alexander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Teacher Resource Guide

Theater at Monmouth 2015 Page to Stage Tour Teacher Resource Guide Inside This Guide 1 From the Page to the Stage 6 Who’s Who in the Play 2 Little Red Riding Hood 7 Map of Red’s Journey 3 The True History of Little Red 8 Before the Performance 4 From Cautionary to Fairy Tale 9 After the Performance 5 Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf 10 Resources & Standards From the Page to the Stage This season, the Theater at Monmouth’s Page to Stage Tour brings a world premiere adaptation of classic literature to students across Maine. The True Story of Little Red (grades Pre-K-8) was adapted to build analytical and literacy skills through the exploration of verse and playwriting, foster creativity and inspire imaginative thinking. Page to Stage Tour workshops and extended residencies offer students the opportunity to study, explore, and view classic literature through performance. TAM’s Education Tours and complimentary programming challenge learners of all ages to explore the ideas, emotions, and principles contained in classic texts and to discover the connection between classic theatre and our modern world. Teacher Resource Guide information and activities were developed to help students form a personal connection to the play before attending the production; standards- based activities are included to explore the plays in the classroom before and after the performance. The best way to appreciate classic literature is to explore. That means getting students up on their feet and physically, emotionally, and vocally exploring the words. The kinesthetic memory is the most powerful—using performance-based activities will help students with a range of learning styles to build a richer understanding of the language and identify with the characters and conflicts of the plays. -

Mother Goose, Inc

MOTHER GOOSE, INC. Story, music and lyrics by Stephen Murray Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy in anyway or perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co. Inc. Call the publisher for further scripts and licensing information. On all programs and advertising the author’s name must appear as well as this notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Co.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY INC. www.histage.com © 1996 by Stephen Murray Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing http://www.histage.com/playdetails.asp?PID=1244 Mother Goose, Incorporated 2 STORY OF THE PLAY Mother Goose and the Brothers Grimm have been in competition for over 200 years and the friction between them doesn’t seem to be abating. The poor Big Bad Wolf is caught in the middle of all this feuding. He has 12 cubs to feed and is working on the sly for both Mother Goose and the Brothers Grimm. He is constantly falling asleep at the wrong times. The war is heating up so Mother Goose has been pretty cranky lately, and her employees beg her to take a vacation. She takes off to a beautiful island resort leaving Simple Simon in charge. Simon lets the power go to his head and spends money like crazy, and the Goose employees go on strike. The only way Simon can bring them back to work and get the company out of the red is to agree to appear on a fairy tale TV special with the Brothers Grimm employees. -

Tesis En El Extranjero Y Mi Amazon.Com Personalizado

UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ANDRÉS BELLO Facultad de Humanidades y Educación Escuela de Comunicación Social Mención Artes Audiovisuales “Trabajo de Grado” DE PIEDRADURA A SPRINGFIELD ANÁLISIS DEL LENGUAJE AUDIOVISUAL EN DOS SERIES DE DIBUJOS ANIMADOS Tesista María Dayana Patiño Perea Tutor: Valdo Meléndez Materán CARACAS, VENEZUELA 2004 A mis padres, Higgins y Francia. AGRADECIMIENTOS A Dios, por todas sus bendiciones. A mi papá, mi gran amor. Tu me has enseñado a sentarme y pensar, a levantarme y seguir y a luchar para conseguir mi lugar en esta vida. Eres mi mejor ejemplo y mi más grande orgullo. A mi mamá, por tu amor, tu nobleza, tu sabiduría y tu apoyo incoanaal ndicional, no importa la hora ni las distancias. Eres la mujer más maravillosa del mundo y yo tengo la suerte de que seas mi compañía y mi descanso en cada paso que doy. A mis hermanos, hermanas, cuñadas, tíos y primos, porque cada uno, alguna vez, sacó un momento de su tiempo para preguntar ¿cómo va la tesis? y, considerando el tamaño, ¿a quién se le puede olvidar una pregunta que te han hecho unas doscientas veces?...Los quiero a todos, infinitas gracias. A María Bethania Medina, Gabriela Prado y Carolina Martínez por el apoyo moral y los momentos de ocio, justificados o no, las quiero muchísimo. Gracias por tanto aguante. A Olivia Liendo, amiga, gracias por tantas sesiones de consulta cibernética y por ser, además, mi sensei y despertador personal. A Luis Manuel Obregón, mi compañero de tesis ad honorem . Primo, gracias por todo el tiempo y el apoyo que me diste para salir adelante en esto (y gracias también por todo el delivery)...muchacho, you rock! A Sasha Yánez, por la compañía durante tantos trasnochos y las conversaditas en el balcón. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Fraternite! Eqalite!

VOL. 119 - NO. 3 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, JANUARY 16, 2015 $.35 A COPY Liberte! Fraternite! Eqalite! by Sal Giarratani This past Saturday, a large How can we defeat an en- crowd gathered on the emy if we won’t even prop- Boston Common standing in erly identify who that enemy solidarity with millions of is? Even the new Presi- people in Paris’ Place de la dent of Egypt Abdel-Fattah Republique against Radical el-Sissi has courageously Islamic acts of terror that spoken for the need for a killed 17 people last week. Revolution in Islam and for Some 40 world leaders countering those who mis- joined arms together in sup- use the religion of Muslims. port of France and against On second thought, per- those seeking civilization haps Obama didn’t belong jihad. in that recent gathering in Many marched together in Paris since the world needed support of those values of to see leaders linking arms modern civilization under with one another. attack today. It was a march We insulted not only for liberty. It was a march for the French of 2015, we in- all of us. It was also a march sulted the bond between against those using reli- our nations built up since gious fanaticism and killing the days of the American innocents in the name of White House, it was a dumb send Vice President Joe was a deliberate move not to Revolution. their God. mistake that America went Biden or Secretary of State link the United States of We must not be afraid to Why wasn’t President AWOL at this world-wide John F. -

American WWII Propaganda Cartoons

Name _____________________________________ Date ________________________ Period ______ American WWII Propaganda Cartoons “Blitz Wolf” – A cartoon produced in 1942 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Short Subject Cartoon. The plot is a parody of the Three Little Pigs, told from a WWII anti-German propaganda perspective. As you watch the cartoon, answer the following questions: Who do the Three Little Pigs represent? Who does the Wolf represent? What does this cartoon say about America’s view of Germany and Hitler? “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap” - A 1942 one-reel animated cartoon short subject released by Paramount Pictures. It is one of the best-known World War II propaganda cartoons. The cartoon gets its title from a novelty song written by James Cavanaugh, John Redmond and Nat Simon. As you watch the cartoon, answer the following questions: Who does Popeye represent? How are the Japanese portrayed? What does this cartoon say about America’s view of Japan and its people? Using complete sentences, answer the following questions about the use of animated cartoons for anti- war propaganda. 1. Is the use of animation and humor appropriate for depicting the serious nature of war? Use at least 2 specific examples to explain your opinion. 2. The U.S. has been fighting the War on Terror for over a decade. If such propaganda cartoons were made today featuring Iraqis, Afghans, or others targeted in the War on Terror, would they be accepted? Would they be considered offensive? Use at least 2 specific examples to explain your opinion. -

Fall 2020Fall 2020

HarE JoHn HarE Students dressed is a freelance illustrator and in deep-sea diving graphic designer who works on Field Trip suits travel to the a range of projects. He lives in ocean deep in a yellow Gladstone, Missouri, with his submarine school bus. wife and two children. When they get there, they are introduced to creatures like T PRAISE FOR Field Trip to the Moon o luminescent squids and giant T he isopods, and discover an old ocean deep shipwreck. But when it’s time to return to the submarine bus, one student lingers to take a photo of a treasure chest and A Junior Library Guild Selection falls into a deep ravine. Luckily, A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year the child is entertained by a The Horn Book Fanfare List mysterious sea creature until ★ “Hare’s picture book debut is a winner . being retrieved by the teacher. A beautifully done wordless story about BOOKS FERGUSON MARGARET In his follow-up to Field Trip to a field trip to the moon with a sweet and funny alien encounter.”—School Library the Moon, John Hare’s rich, Journal, starred review atmospheric art in this wordless “[An] auspicious debut presents a world picture book invites children where a yellow crayon box shines Holiday House to imagine themselves in the like a beacon.”—Booklist story—a story full of surprises. MARGARET FERGUSON BOOKS BOOKS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE US $17.99$17.99 / CAN / CAN $23.99 $23.99 ISBN: 978-0-8234-4630-8 Holiday House Publishing, Inc. 5 1 7 9 9 HolidayHouse.com EAN Fall 2020 Printed in China 9 780823 446308 0408 Reinforced Illustration © 2020 by John Hare from Field Trip to the Ocean Deep HOLIDAY HOUSE Apples Gail Gibbons Summary Find out where your favorite crunchy, refreshing fruit comes from in this snack-sized book. -

Cartooning America: the Fleischer Brothers Story

NEH Application Cover Sheet (TR-261087) Media Projects Production PROJECT DIRECTOR Ms. Kathryn Pierce Dietz E-mail: [email protected] Executive Producer and Project Director Phone: 781-956-2212 338 Rosemary Street Fax: Needham, MA 02494-3257 USA Field of expertise: Philosophy, General INSTITUTION Filmmakers Collaborative, Inc. Melrose, MA 02176-3933 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story Grant period: From 2018-09-03 to 2019-04-19 Project field(s): U.S. History; Film History and Criticism; Media Studies Description of project: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story is a 60-minute film about a family of artists and inventors who revolutionized animation and created some of the funniest and most irreverent cartoon characters of all time. They began working in the early 1900s, at the same time as Walt Disney, but while Disney went on to become a household name, the Fleischers are barely remembered. Our film will change this, introducing a wide national audience to a family of brothers – Max, Dave, Lou, Joe, and Charlie – who created Fleischer Studios and a roster of animated characters who reflected the rough and tumble sensibilities of their own Jewish immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. “The Fleischer story involves the glory of American Jazz culture, union brawls on Broadway, gangsters, sex, and southern segregation,” says advisor Tom Sito. Advisor Jerry Beck adds, “It is a story of rags to riches – and then back to rags – leaving a legacy of iconic cinema and evergreen entertainment.” BUDGET Outright Request 600,000.00 Cost Sharing 90,000.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 690,000.00 Total NEH 600,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly Mcgill BA, University Of

Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly McGill B.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art & Art History 2018 i This thesis entitled: Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History written by Molly McGill has been approved for the Department of Art and Art History Date (Dr. Brianne Cohen) (Dr. Kirk Ambrose) (Dr. Denice Walker) The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the Department of Art History at the University of Colorado at Boulder for their continued support during the production of this master's thesis. I am truly grateful to be a part of a department that is open to non-traditional art historical exploration and appreciate everyone who offered up their support. A special thank you to my advisor Dr. Brianne Cohen for all her guidance and assistance with the production of this thesis. Your supervision has been indispensable, and I will be forever grateful for the way you jumped onto this project and showed your support. Further, I would like to thank Dr. Kirk Ambrose and Dr. Denice Walker for their presence on my committee and their valuable input. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Catherine Cartwright and Jean Goldstein for listening to all my stress and acting as my second moms while I am so far away from my own family. -

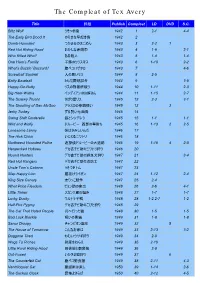

The Compleat of Tex Avery

The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. Blitz Wolf うそつき狼 1942 1 2-1 4-4 The Early Bird Dood It のろまな早起き鳥 1942 2 Dumb-Hounded つかまるのはごめん 1943 3 2-2 1 Red Hot Riding Hood おかしな赤頭巾 1943 4 1-9 2-1 Who Killed Who? ある殺人 1943 5 1-4 1-4 One Ham’s Family 子豚のクリスマス 1943 6 1-10 2-2 What’s Buzzin’ Buzzard? 腹ペコハゲタカ 1943 7 4-6 Screwball Squirrel 人の悪いリス 1944 8 2-5 Batty Baseball とんだ野球試合 1944 9 3-5 Happy-Go-Nutty リスの刑務所破り 1944 10 1-11 2-3 Big Heel-Watha インディアンのお婿さん 1944 11 1-15 2-7 The Screwy Truant さぼり屋リス 1945 12 2-3 3-1 The Shooting of Dan McGoo アラスカの拳銃使い 1945 13 3 Jerky Turkey ずる賢い七面鳥 1945 14 Swing Shift Cinderella 狼とシンデレラ 1945 15 1-1 1-1 Wild and Wolfy ドルーピー 西部の早射ち 1945 16 1-13 2 2-5 Lonesome Lenny 僕はさみしいんだ 1946 17 The Hick Chick いじわるニワトリ 1946 18 Northwest Hounded Police 迷探偵ドルーピーの大追跡 1946 19 1-16 4 2-8 Henpecked Hoboes デカ吉チビ助のニワトリ狩り 1946 20 Hound Hunters デカ吉チビ助の野良犬狩り 1947 21 3-4 Red Hot Rangers デカ吉チビ助の消防士 1947 22 Uncle Tom’s Cabana うそつきトム 1947 23 Slap Happy Lion 腰抜けライオン 1947 24 1-12 2-4 King Size Canary 太りっこ競争 1947 25 2-4 What Price Fleadom ピョン助の家出 1948 26 2-6 4-1 Little Tinker スカンク君の悩み 1948 27 1-7 1-7 Lucky Ducky ウルトラ子鴨 1948 28 1-2 2-7 1-2 Half-Pint Pygmy デカ吉チビ助のこびと狩り 1948 29 The Cat That Hated People 月へ行った猫 1948 30 1-5 1-5 Bad Luck Blackie 呪いの黒猫 1949 31 1-8 1-8 Senor Droopy チャンピオン誕生 1949 32 5 The House of Tomorrow こんなお家は 1949 33 2-13 3-2 Doggone Tired ねむいウサギ狩り 1949 34 2-9 Wags To Riches 財産をねらえ 1949 35 2-10 Little Rural Riding Hood 田舎狼と都会狼 1949 36 2-8 Out-Foxed いかさま狐狩り 1949 37 6 The Counterfeit Cat 腹ペコ野良猫 1949 38 2-11 4-3 Ventriloquist Cat 腹話術は楽し 1950 39 1-14 2-6 The Cuckoo Clock 恐怖よさらば 1950 40 2-12 4-5 The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C.