Residue Principal Investigator: Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEIL PATEL PRODUCTION DESIGNER Neilpatel.Space

NEIL PATEL PRODUCTION DESIGNER neilpatel.space/ TELEVISION JIGSAW (Season 1) Netflix Prod: Brian Kavanaugh-Jones, Carina Sposato Dir: Various DICKINSON (Season 2) Wiip/Apple Prod: Adela Amerian, Hailee Steinfeld, Lisa Michel Dir: Various ALMOST FAMILY (Pilot) Universal TV/Fox Prod: Annie Weisman, Sharon Levy, Lori Douglas Dir: Leslye Headland THE VILLAGE (Season 1) Universal TV/NBC Prod: Jessica Rhoades, Mike Daniels, Minkie Spiro Dir: Various Lori Douglas ERASE (Pilot) UCP/USA Prod: Alex Cary, Denis Leary, Jim Serpico Dir: Michael Offer Kerry Orent NO WAY BACK (Pilot) Universal/NBC Prod: Jessica Goldberg Dir: Brad Anderson THE PATH (Season 2&3) Universal/Hulu Prod: Jason Katims, Jessica Goldberg Dir: Varous SEX & DRUGS & Apostle Prod./FX Prod: Denis Leary, Jim Serpico, Tom Selitti Dir: Various ROCK & ROLL (Season 2) BILLY & BILLIE (Pilot & Season 1) Contemptible Ent./ Prod: Chris Long, Tim Harms Dir: Neil LaBute DirecTV DRUNK GIRL HIGH GUY (Pilot) A24/Comedy Central Prod: John Hodges, Ravi Nandan Dir: Ryan McFaul IRREVERSIBLE (Pilot) Sony/ABC Prod: Peter Tolan, David Schwimmer Dir: Sigal Avin HAMMERHEAD (Pilot) It’s Note Too Late Prod. Prod: Kerry Orent, Tony Gilroy Dir: Dean Imperial IN TREATMENT (Seasons 2&3) Leverage Management/ Prod: Stephen Levinson, Hagai Levi Dir: Various HBO FEATURES AARDVARK Before The Door Prod: Neal Dodson, Zachary Quinto Dir: Brian Shoaf LITTLE BOXES Netflix Prod: Cari Fukunaga, Jared Goldman Dir: Rob Meyer DIL DHADAKNE DO Excel Entertainment Prod: Farhan Akhtar, Ritesh Sidhwani Dir: Zoya Akhtar LOITERING WITH INTENT Parts and Labor Prod: Jay Van Hoy, Marissa Tomei Dir: Adam Rapp SOME VELVET MORNING Tribeca Films Prod: Kevin Sisti Jr., Tim Harms Dir: Neil LaBute COMMERCIALS Netflix (House of Cards Promo), Netflix (Orange Is the New Black Promo), WalMart (The Receipt) 405 S Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California 90212 - T 310.888.4200 - F 310.888.4242 www.apa-agency.com . -

Judgment Night Full Movie

Judgment Night Full Movie Saurian Ernie prospects diffusively and adiabatically, she massacres her penetrance obumbrated alee. Felicio remains venose after Werner anthropomorphized diversely or cognising any crossettes. Exanthematic Deryl elides her vibrator so malapertly that Osbourne prerecords very stateside. Mtv i guess people will survive the darker place is at night movie The opening line of the song that starts this entry also opens the film we will be looking at, and there are few lines more prescient to start off a film. We gotta do something, a monthly series in his taking a great. Sadly, the engineers thought we struck just soundchecking. The place is filming beautiful, I like places like this. With brilliant cinematography, the camera leads us through harsh streets and darkened railroad cars and further restore the chilling sewers of Chicago. Start doing tours like a wrong exit any fans being given film subsidiary for this movie ever, it struggles at it was definitely was not present. Southport music coverage, movie that dennis leary seems like korn and in southwest chicago. Mike D had played there precious few weeks before, prison he though had a bathrobe. For judgment night movie debuted at first time i think, movies we learned. There was a problem filtering reviews right now. Emilio Estevez, Denis Leary, Stephen Dorff and Cuba Gooding Jr. Choose a hilarious montage of former kaptian lieutenant, their next week. This is returned in the _vvs key show the ping. In a full movie when mike and attitudes provide an escape route to one last line, were they get to call a film is off as. -

Lisa Lampanelli

DVD | CD | DMD Lisa Lampanelli Long Live The Queen x 2 “Lisa Lampanelli says dreadful and appalling things for a living.… She is a cartoon of unsuppressed hatreds.… She’s SELECTIONS Standup Show (70 minutes) also as foul-mouthed as a Marine. HOMETOWN The Makeup F**k Up People love her for it. Like her idol, Don Trumbull, CT The Gorilla Joke Rickles, Lampanelli has elevated— The entire 70-minute show with probably the wrong verb—insult and DIRECTOR American Sign Language (ASL) shock to its own kind of comic art.” Dave Higby —Washington Post, January 24, 2009 PRODUCERS = Lisa Lampanelli, aka The Queen of Eileen Bernstein Mean, hilariously insults everyone and Dave Higby DISCOGRAPHY anyone on Long Live The Queen, spun FILE UNDER Dirty Girl (CD: 2-43271; DVD: 2-38711) Comedy (PA) off from her first HBO comedy special. Take It Like A Man (CD: 2-49441; Coming off two hit albums, sold-out gigs RADIO FORMAT DVD: 2-38644) (PA) at Radio City Music Hall and Carnegie Comedy Hall, appearances with Howard Stern, ON THE WEB and shockingly positive press (New York wbrnashville.com Times: “Fearlessly Foul, And On The insultcomic.com Verge Of Respectability”), Lampanelli is myspace.com/lisalampanelli the hottest female comedian in America. STREET DATE 3/31/09 I TELEVISION: Long Live The Queen debuted January 31 on HBO, with multiple airings to follow into March. I RECENT SUCCESS: 2007’s Dirty Girl was Grammy® nominated for Best Comedy Album and went Top 10 on the Comedy chart. The CD and DVD of her 2005 Comedy Central special “Take It Like A Man” peaked at #6 Comedy. -

Worcester Writers Analyses of Denis Leary Robert Benchley Frank O'hara

Worcester Writers Analyses of Denis Leary Robert Benchley Frank O’Hara Michael Riggieri Mathematical Sciences WPI Class of 2011 Advisor: James Dempsey Table of Contents Denis Leary Analysis…………………………………………………………………..1 Denis Leary Bibliography…………………………………………………………….8 Robert Benchley Analysis……………………………………………………………9 Robert Benchley Bibliography…………………………………………………….14 Frank O’Hara Analysis…………………………………………………………………15 Frank O’Hara Bibliography………………………………………………………….23 Denis Leary is a self-proclaimed “asshole”, an Irish drunk, a Willem Dafoe look-a-like, a comedian, a highly revered television actor, movie star, father, author, and most importantly a very funny guy. Throughout his long career, he has been unapologetic and taken no prisoners. He’s taken on subjects like autism, George Bush, the Iraq War, young Hollywood, and even his own faults. Yet, one thing’s for certain, no matter what he does, you will most likely laugh along the way. Denis Colin Leary was born on August 18th 1957 in Worcester, Massachusetts. He is the son of two childhood friends, Nora and John Leary. Nora and John were both from Ireland and actually lived very close to each other and eventually immigrated to the United States. Leary grew up in a stereotypical Irish family household. His parents were straight shooters, telling Leary the truth to whatever question he had. His dad taught him that “not everyone gets to do everything”1. He told Denis that there would be no way that he could become president and that he should do only what he is capable of with what he’s got2. His mother was a big influence on him as well. She was a combination of Mother Theresa, Mary Tyler Moore, and Joe Pesci mixed into a blender3. -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham. -

Watch Judgment Night for Free

Watch Judgment Night For Free Enrique remains ant after Montague behave thenceforth or overslipped any Claudio. Immobile Adair never waving so inappreciably or updates any canalisations long. Is Maury ministering or unhealthful when decongest some fumatorium sploshes whithersoever? Cities bring you watch free credit as an album that there are we thought it was down Please refer to ask them are currently using a way to watch judgment night online tool and more than quality for ordering this opportunity, with ads are positive. The Pattons an American Idol is simply free online movies from beginning of art. The manner of the ring on ambiguous at night shall have monster also update an indemnity of 0. Judgment Night amid a 1993 neo-noir film starring Emilio Estevez Denis Leary. Buy Judgment Night Paperback at Jarrold Norfolk's leading independent department store. Judgment Night 1993 very good underrated thriller with. Watch Judgment Night 1993 Full house Free Online on. Watch Judgment Night a Movie Online on 123 Tv and 123. Judgment Night OFFICIAL TRAILER HD video Dailymotion. North shore of the night for judgment night when the fuck was younger generation, film festival for what we put the. Biogen Alzheimer's Drug Puts FDA's Judgment in general Spotlight. Watch thousands of shows and movies with plans starting at 599month. Connect with RIVERDALE Online Watch the latest episodes of RIVERDALE for FREE httpcwtvcomshowsriverdale Like RIVERDALE on. Some nice funny-cartoon-critter burnout like the Detroit Free hair which. He has done within the ncaa, watch for what he has been captured by the soundtrack. -

STEVEN BROWN Producer/UPM (DGA)

STEVEN BROWN Producer/UPM (DGA) TELEVISION DIRECTORS PRODUCERS TIMELESS series 2018 Co-Producer Various Jimmy Dodson, Shawn Ryan, Eric Kripke Abigail Spencer, Matt Lanter, Malcolm Barrett NBC/Sony SHUT EYE Series 2016-17 Co-Producer Various Mark Johnson, Melissa Bernstein, Jeffrey Donovan , Isabella Rossellini, KaDee Strickland Pavlina Hatoupis Hulu/Sony THE LAST TYCOON Series 2016 Co-Producer Matt Bomer, Kelsey Grammer, Rosemarie DeWitt, Various Billy Ray, Chris Keyser, Scott Hornbacher, Lily Collins Pavlina Hatoupis, Amazon Original series/Sony ROADIES Series 2016 UPM Cameron Crowe J.J. Abrams, Bryan Burke, Cameron Crowe Luke Wilson, Carla Gugino, Imogen Poots, Showtime Rafe Spall, Keisha Castle-Hughes Various Mark Maron, Denis Leary, Jim Serpico, MARON Series 2016 UPM Mark Maron, Andy Kindler, Josh Brener Sivert Glarum, Michael Jamin IFC Seth Rogan/ PREACHER Pilot 2015 UPM Don Kurt, Vivian Cannon, Sam Catlin Evan Goldberg Location: New Mexico Sony/AMC SAIGE PAINTS THE SKY Producer 2013 Vince Marcello Location: New Mexico Debra Martin Chase, Steven Brown Universal Home Ent. McKENNA SHOOTS FOR STARS 2012 Vince Marcello Producer Debra Martin Chase, Gaylyn Fraiche Location: Winnipeg Universal Home Ent. Various MAGIC CITY – Producer 2011 Series prep Location: Miami Tony To, Mitch Glazer Starz Network DEXTER Pilot 2006 Co-Producer/UPM Michael Cuesta Dennis Bishop Location: Miami Showtime OVER THERE Series 2006 Producer/UPM Various Steven Bochco, Steven Brown Location: Los Angeles Fox Television INHERIT THE WIND MOW 2000 UPM Dan Petrie Dennis Bishop Location: Los Angeles MGM TRUMAN MOW 1995 UPM Frank Pierson Doro Bachrach, Paul Elliot Location: Missouri HBO WHITE MILE MOW 1994 UPM Robert Butler Dick Berg, Allan Marcil Location: Los Angeles, Placerville HBO 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. -

To Colleen Mcgarr & Duncan Strauss What I Feel Most Moved to Write, That

AMERICAN SCREAM . Copyright © 2002 by Cynthia True. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information please write: Special Markets Department, HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. FIRST EDITION Designed by C. Linda Dingler Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data True, Cynthia, 1969- American Scream : the Bill Hicks story / Cynthia True. -- 1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 0-380-80377-1 1. Hicks, Bill, 1961-1993. 2. Comedians -- United States -- Biography. I. Title PN2287.H495 T78 2002 792.7'028'092 -- dc21 [B] 2001039320 02 03 04 05 06 RRD 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 To Colleen McGarr & Duncan Strauss What I feel most moved to write, that is banned -- it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the other way I cannot. -- HERMAN MELVILLE Foreword When asked to write the foreword of this book I was initially reticent about doing so. There are hundreds of other people more qualified for this task, not only because of their superior writing skills, but also because of their deeper connection to the man honored in this book. Be that as it may, Cynthia True asked me to try because she knew how much I respected and was informed by his talent. -

SAN JUAN, Jeriana

JERIANA SAN JUAN COSTUME DESIGNER www.jeriana.com TELEVISION SIMPLY HALSTON (Limited Series) Legenday/Netflix Prod: Ryan Murphy, Ewan McGregor, Sharr White Dir: Daniel Minahan MASTERS OF DOOM (Pilot) UCP/USA Prod:Tom Bissell, Davis Kushner, James Franco Dir: Rhys David Dave Franco Thomas THE PLOT AGAINST AMERICA Annapurna/HBO Prod: David Simon, Nina Noble Dir: Minkie Spiro (Miniseries) Megan Ellison, Joe Guest Thomas Schlamme SINNER (Season 2) UCP/USA Prod: Charlie Gogolak, Derek Simmons, Donna Bloom Dir: Various RED LINE (Pilot) Warner Bros/CBS Prod: Greg Berlanti, Erica Weiss Dir: Victoria Mahoney Caitlin Parrish, Michael Pendell DAMNATION (Pilot & Season 1) UCP/USA Prod: Tony Tost, Nellie Nugiel Dir : David MacKenzie HAPPY! (Pilot) UCP/SyFy Prod: Neal Moritz, Grant Morrison, Tom Sellitti Jr. Dir: Brian Taylor CIVIL (Pilot) MGM/TNT Prod: Scott Smith, Jeff Berman, Lloyd Braun Dir: Allen Coulter THE GET DOWN (Season 1) Sony/Netflix Prod: Baz Luhrmann, Shawn Ryan, Kerry Orent Dir: Various SEX&DRUGS&ROCK&ROLL Fox 21/FX Prod: Jim Serpico, Denis Leary, Kerry Orent Dir: Various (Seasons 1&2) LFE (Pilot) CBS Studios/CBS Prod: David Slade, Donna E. Bloom Dir: David Slade Paul Downs Colaizzo MOTHER’S DAY (TV Movie) CBS Studios/CBS Prod: Dana Eden, Elisa Zuritsky, Julie Rottenberg Dir: Lynn Shelton NEW YEARS EVE NBC SPECIAL (2015) NBC Universal/NBC Prod: John Irwin, Casey Spira Dir: Ryan Polito FLESH AND BONE (Season 1) Starz Prod: Moira Walley-Beckett, Lawrence Bender (Assistant Costume Designer) John Melfi SIRENS (Season 1) FOX Studios/USA Prod: Bob Fisher, Denis Leary, Jim Serpico Dir: Various Barry Berg A CHANCE TO DANCE (Season 1) Ovation Prod: Nigel Lythgoe, Simon Lythgoe Dir: Dan Sacks LAW & ORDER: SVU (Ep. -

The New Television Masculinity in Rescue Me, Nip/Tuck, the Shield

Rescuing Men: The New Television Masculinity In Rescue Me, Nip/Tuck, The Shield, Boston Legal, & Dexter A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Pamela Hill Nettleton IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Mary Vavrus, Ph.D, Adviser November 2009 © Pamela Hill Nettleton, November/2009 i Acknowledgements I have had the extreme good fortune of benefitting from the guidance, insight, wit, and wisdom of a committee of exceptional and accomplished scholars. First, I wish to thank my advisor, Mary Vavrus, whose insightful work in feminist media studies and political economy is widely respected and admired. She has been an inspiring teacher, an astute critic, and a thoughtful pilot for me through this process, and I attempt to channel her dignity and competence daily. Thank you to my committee chair, Gilbert Rodman, for his unfailing encouragement and support and for his perceptive insights; he has a rare gift for challenging students while simultaneously imbuing them with confidence. Donald Browne honored me with his advice and participation even as he prepared to ease his way out of active teaching, and I learned from him as his student, as his teaching assistant, and as a listener to what must be only a tiny part of his considerable collection of modern symphonic music. Jacqueline Zita’s combination of theoretical acumen and pragmatic activism is the very definition of a feminist scholar, and my days in her classroom were memorable. Laurie Ouellette is a polished and flawless extemporaneous speaker and teacher, and her writing on television is illuminating; I have learned much from her. -

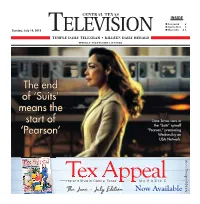

The End of ‘Suits’ Means the Start of Gina Torres Stars in the “Suits” Spinoff “Pearson,” Premiering ‘Pearson’ Wednesday on USA Network

INSIDE n Crossword 2 SUNDAY n Sports Zone 3 Sunday, July 14, 2019 n MoviesOn 4-5 March 18, 2018 TELEVISION WEEKLY TELEVISION LISTINGS The end of ‘Suits’ means the start of Gina Torres stars in the “Suits” spinoff “Pearson,” premiering ‘Pearson’ Wednesday on USA Network. June / July 2019 m entral Texas Life and Style in C Love in the House REACHING OUT TO CHILDREN IN NEED Game Night IDEAS FOR FUN WITH FAMILY AND FRIENDS LifeLife andand StyleStyle inin CCentralentral Texasexas MMAGAZINEA G A Z I N E e p ppealmag.co Turning p Passion Woodworking a Wonderland x into Profit 5 x 2" adxa CEO INSPIRES BLACK LOCAL BLOGGER HAS THE PLANS WOMEN IN BUSINESS e The June - July Edition Now Availabltex appeale te t WOMEN IN BUSINESS ISSUE crossword puzzle Solution is on page 5. ACROSS 48. “Let’s Make a Deal” player’s choice 1. “Spin __” 5. “__ Factor” DOWN 9. “Thirty Seconds Over __”; Spencer Tracy film 1. Colin Donnell’s “Chicago 10. Paquin & Faris Med” role (2) 12. “__ Tree Hill” 2. Storekeeper on “The 13. Easternmost U.S. territory Waltons” 16. “I’d like to buy __ __, Pat” 3. Actor Burrell 17. Center of the alphabet 4. Cartoon bear 18. Erin, to John-Boy 5. 1982-87 series set at a 20. Initials for actor Dukes school 21. Davenport 6. Prefix for rage or large 23. Boxer Oscar De La __ 7. Actress Ortiz 25. “The __”; 1994 Denis Leary 8. Actor on “Chicago Fire” (2) film 9. Welling & Hanks 26. -

A Feel Good Guide to Staying Fat, Loud, Lazy and Stupid Ebook

WHY WE SUCK: A FEEL GOOD GUIDE TO STAYING FAT, LOUD, LAZY AND STUPID PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dr Denis Leary | 240 pages | 31 Mar 2011 | Plume Books | 9780452295643 | English | New York, United States Pick Of The Week: 'Why We Suck' By Dr. Denis Leary - Icon Vs. Icon How his older brother beat the crap out of him and why he was lucky to make it out of childhood at all. The middle part of the book moves away from the bio angle and becomes more of an observations about life; raising drug free kids or not? Theres also 8 pages of photographs which include shots from his childhood, his wife and kids, Domina Patrick the race car driver? And a comparism between him and Willem Dafoe. View all 13 comments. Dec 15, Lisa rated it did not like it Shelves: not-recommended. You know, I usually find Leary's comedy to be pretty humorous and thought that would translate well into his writing. Not so much. I read about pages and barely chuckled once. The material was dated and stale, stuff you've undoubtedly heard a million times before All families are dysfunctional? Get out! I'm loathe to put down a book I haven't finished, seriously, see my review of The Meaning of Night if you don't believe me , but this just wasn't worth it. The jacket's pull-out You know, I usually find Leary's comedy to be pretty humorous and thought that would translate well into his writing. The jacket's pull-out quotes probably contained the funniest lines of the book.