Elite Strategies and the Formulation of a French Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A C C E P T E

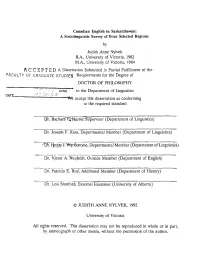

Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions by Judith Anne Nylvek B.A., University of Victoria, 1982 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 ACCEPTE.D A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .>,« 1,^ , I . I l » ' / DEAN in the Department of Linguistics o ate y " /-''-' A > ' We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Xjx. BarbarSTj|JlA^-fiVSu^rvisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Joseph F. Kess, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) CD t. Herijy J, WgrKentyne, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) _________________________ Dr. Victor A. 'fiJeufeldt, Outside Member (Department of English) _____________________________________________ Dr. Pajtricia E. Ro/, Additional Member (Department of History) Dr. Lois Stanford, External Examiner (University of Alberta) © JUDITH ANNE NYLVEK, 1992 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Dr. Barbara P. Harris ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to provide detailed information regarding Canadian English as it is spoken by English-speaking Canadians who were born and raised in Saskatchewan and who still reside in this province. A data base has also been established which will allow real time comparison in future studies. Linguistic variables studied include the pronunciation of several individual lexical items, the use of lexical variants, and some aspects of phonological variation. Social variables deemed important include age, sex, urbanlrural, generation in Saskatchewan, education, ethnicity, and multilingualism. The study was carried out using statistical methodology which provided the framework for confirmation of previous findings and exploration of unknown relationships. -

A Finding Aid to the Emigration And

A Finding Aid to the Emigration and Immigration Pamphlets Shortt JV 7225 .E53 prepared by Glen Makahonu k Shortt Emigration and Immi gration Pamphlets JV 7225 .E53 This collection contains a wide variety of materials on the emigration and immigration issue in Canada, especially during the period of the early 20th century. Two significant groupings of material are: (1) The East Indians in Canada, which are numbered 24 through 50; and (2) The Fellowship of the Maple Leaf, which are numbered 66 through 76. 1. Atlantica and Iceland Review. The Icelandic Settlement in Cdnada. 1875-1975. 2. Discours prononce le 25 Juin 1883, par M. Le cur6 Labelle sur La Mission de la Race Canadienne-Francaise en Canada. Montreal, 1883. 3. Immigration to the Canadian Prairies 1870-1914. Ottawa: Information Canada, 19n. 4. "The Problem of Race", The Democratic Way. Vol. 1, No. 6. March 1944. Ottawa: Progressive Printers, 1944. 5. Openings for Capital. Western Canada Offers Most Profitable Field for Investment of Large or Small Sums. Winnipeg: Industria1 Bureau. n.d. 6. A.S. Whiteley, "The Peopling of the Prairie Provinces of Canada" The American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 38, No. 2. Sept. 1932. 7. Notes on the Canadian Family Tree. Ottawa: Dept. of Citizenship and Immigration. 1960. 8. Lawrence and LaVerna Kl ippenstein , Mennonites in Manitoba Thei r Background and Early Settlement. Winnipeg, 1976. 9. M.P. Riley and J.R. Stewart, "The Hutterites: South Dakota's Communal Farmers", Bulletin 530. Feb. 1966. 10. H.P. Musson, "A Tenderfoot in Canada" The Wide World Magazine Feb. 1927. 11. -

A Thesis for the Degree of University of Regina Regina, Saskatchewan

Hitched to the Plow: The Place of Western Pioneer Women in Innisian Staple Theory A Thesis Subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology University of Regina by Sandxa Lynn Rollings-Magnusson Regina, Saskatchewan June, 1997 Copyright 1997: S.L. Rollings-Magnusson 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de micro fi ch el^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemîse de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Romantic images of the opening of the 'last best west' bring forth visions of hearty pioneer men and women with children in hand gazing across bountiful fields of golden wheat that would make them wealthy in a land full of promise and freedom. The reality, of course, did not match the fantasy. -

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

Physician to Physician Is CII/CPAR Right for You? Monday, April 26Th – 5:00 to 6:00Pm Dr

Edmonton Zone Physician to Physician Is CII/CPAR Right for You? Monday, April 26th – 5:00 to 6:00pm Dr. Janet Craig, Edmonton West PCN & Dr. Ron Shute, Edmonton Southside PCN April 26, 2021 Supported by: 1 Live Recording • Privacy Statement: The session you are participating in is being recorded. By participating, you understand and consent to the session being made publicly available via a link on the AMA – ACTT website or any Edmonton Zone PCN website for an undetermined length of time. • By participating in the live Q&A, your name as entered into the Zoom sign-in may be visible to other participants during the session and/or in the recording. 2 Land Acknowledgment We would like to recognize that we are webcasting from, and to, many different parts of Alberta today. The province of Alberta is located on Treaty 6, Treaty 7 and Treaty 8 territory and is a traditional meeting ground and home for many Indigenous Peoples. 3 Asking Questions • At any time, type questions in the Chat • At the end we will also invite you to ask live questions • Click on “Participants” • Use the ‘Raise Hand’ feature To raise • A moderator will invite you to your hand unmute 4 Co-Presenters this Evening Edmonton West PCN Edmonton Southside PCN Joshna Tambe Leslie Bortolotto Quality Improvement Consultant Improvement Facilitator 55 Chat Moderators & Session Support Team • Rajvir Kaur - Quality Improvement Consultant, Edmonton West PCN • Stephanie Balko - Improvement Facilitator, Southside PCN • AMA – Accelerating Change Transformation Team • Angille Heintzman • Kendall Olson • Kylie Kidd Wagner • Chris Diamant • Edna DeChamplain 6 Disclosure of Financial Support This program has not received any financial or in-kind support. -

Candidate's Statement of Unpaid Claims and Loans 18 Or 36 Months

Candidate’s Statement of Unpaid Claims and Loans 18 or 36 Months after Election Day (EC 20003) – Instructions When to use this form The official agent for a candidate must submit this form to Elections Canada if unpaid amounts recorded in the candidate’s electoral campaign return are still unpaid 18 months or 36 months after election day. The first update must be submitted no later than 19 months after the election date, covering unpaid claims and loans as of 18 months after election day. The second update must be submitted no later than 37 months after election day, covering unpaid claims and loans as of 36 months after election day. Note that when a claim or loan is paid in full, the official agent must submit an amended Candidate’s Electoral Campaign Return (EC 20120) showing the payments and the sources of funds for the payments within 30 days after making the final payment. Tips for completing this form Part 1 ED code, Electoral district: Refer to Annex I for a list of electoral district codes and names. Declaration: The official agent must sign the declaration attesting to the completeness and accuracy of the statement by hand. Alternatively, if the Candidate’s Statement of Unpaid Claims and Loans 18 or 36 Months after Election Day is submitted online using the Political Entities Service Centre, handwritten signatures are replaced by digital consent during the submission process. The official agent must be the agent in Elections Canada’s registry at the time of signing. Part 2 Unpaid claims and loans: Detail all unpaid claims and loans from Part 5 of the Candidate’s Electoral Campaign Return (EC 20121) that remain unpaid. -

Grid Export Data

Public Registry of Designated Travellers In accordance with the Members By-law, a Member of the House of Commons may designate one person, other than the Member’s employee or another Member who is not the Member’s spouse, as their designated traveller. The Clerk of the House of Commons maintains the Public Registry of Designated Travellers. This list discloses each Member’s designated traveller. If a Member chooses not to have a designated traveller, that Member’s name does not appear on the Public Registry of Designated Travellers. The Registry may include former Members as it also contains the names of Members whose expenditures are reported in the Members’ Expenditures Report for the current fiscal year if they ceased to be a Member on or after April 1, 2015 (the start of the current fiscal year). Members are able to change their designated traveller once every 365 days, at the beginning of a new Parliament, or if the designated traveller dies. The Public Registry of Designated Travellers is updated on a quarterly basis. Registre public des voyageurs désignés Conformément au Règlement administratif relatif aux députés, un député de la Chambre des communes peut désigner une personne comme voyageur désigné sauf ses employés ou un député dont il n’est pas le conjoint. La greffière de la Chambre des communes tient le Registre public des voyageurs désignés. Cette liste indique le nom du voyageur désigné de chaque député. Si un député préfère ne pas avoir de voyageur désigné, le nom du député ne figurera pas dans le Registre public des voyageurs désignés. -

St. Eugene De Mazenod Had a “Zeal for the Kingdom of God” That Was Infectious

Saint Eugene De Mazenod Feast Day: May 21st Born Charles Joseph Eugene de Mazenod on August 1, 1782 into a wealthy family in the south of France, his life was quickly transformed by the French Revolution. At the age of 8, he fled France with his family to Italy as political refugees. Following an eleven-year exile, Mazenod returned to France when he was 20 years old; it was a whole new world. Distressed by the state of the Church in France, Mazenod felt called to the priesthood; he was ordained December 21, 1811 in Amiens, a city in northern France. Eventually, he returned to his hometown, Aix-end-Provence. He focused his ministry on the less fortunate – such as prisoners, youth, servants, workers, and country villagers. His preaching in the local language, rather than French, led to some local opposition by other members of the church. He engaged in an “intense community life of prayer, study and fellowship” along with a group of other “equally zealous priests,” according to the Vatican. These men, once called the Missionaries of Provence, became known as the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate in 1826 with Pope Leo XII’s approval. When he founded the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, the congregation primarily served the “spiritually needy” on the French countryside but eventually expanded their ministry to Switzerland, England and Ireland, at first, and then to Canada, USA and parts of Africa. This missionary order spread throughout the world – living out their motto, “He has sent me to evangelize the poor,” by establishing a deep spiritual foundation, close community life and a visible, unfettered love for the less fortunate. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

PF Vol6 No1.Pdf (9.908Mb)

PRAIRIE FORUM VoI.6,No.1 Spring 1981 CONTENTS F.W.G. Haultain, Territorial Politics and the Quasi-party System Sta"nley Gordon The WCTU on the Prairies, 1886-1930: An Alberta-Saskatchewan Comparison 17 Nancy M. Sheehan Soldier Settlement and Depression Settlement in the Forest 35 Fringe of Saskatchewan John McDonald The Conservative Party of Alberta under Lougheed, 1965-71: Building an Image and an Organization 57 Meir Serfaty The Historiography of the Red River Settlement, 1830-1868 75 Frits Pannekoek Prairie Theses, 1978-79 87 Book Reviews (see overleaf) 101 PRAIRIE FORUM is published twice yearly, in Spring and Fall,at an annual subscription of $15.00. All subscriptions, correspondence and contribu tions should be sent to The Editor, Prairie Forum, Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, Regina,Saskatchewan, Canada, S4S OA2. Subscribers will also receive the Canadian Plains Bulletin, the newsletter of the Canadian Plains Research Center. PRAIRIE FORUM is not responsible for statements, either of fact or of opinion, made by contributors. COPYRIGHT1981 ISSN0317-6282 CANADIAN PLAINS RESEARCH CENTER BOOK REVIEWS paNTING, J.R. and GIBBINS, R., Out of Irrelevance 101 by D. Bruce Sealey KROTZ, lARRY, Urban Indians: The Strangers in Canada's Cities 102 by Oliver Brass KROETSCH, ROBERT, ed., Sundogs: Stories from Saskatchewan 104 by Donald C. Kerr DURIEUX, MARCEL, Ordinary Heroes: The Journal of a French Pioneer in Alberta by Andre Lalonde 106 BOCKING, D.H., ed., Pages from the Past: Essays on Saskatchewan , History by Elizabeth Blight 107 OWRAM, DOUG, Promise of Eden: The Canadian Expansionist Movement and the Idea of the West, 1856-1900 110 by Donald Swainson KOESTER, C.B., Mr. -

Anti-Choice Stance

Members of Parliament with an Anti-choice Stance February 16, 2021 By Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada (See new version, June 5, 2021) History: Prior to 2019 election (last updated Oct 16, 2019) After 2015 election (last updated May 2016) Prior to 2015 election (last updated Feb 2015) After 2011 election (last updated Sept 2012) After 2008 election (last updated April 2011) Past sources are listed at History links. Unknown or Party Total MPs Anti-choice MPs** Pro-choice MPs*** Indeterminate Stance Liberal 154 5 (3.2%) 148 (96%) 1 Conservative 120 81 (66%) 7 32 NDP 24 24 Bloc Quebecois 32 32 Independent 5 1 4 Green 3 3 Total 338 86 (25.5%) 218 (64.5%) 33 (10%) (Excluding Libs: 24%) *All Liberal MPs have agreed and are required to vote pro-choice on any abortion-related bills/motions. **Anti-choice MPs are generally designated as anti-choice based on at least one of these reasons: • Voted in favour of Bill C-225, and/or Bill C-484, and/or Bill C-510, and/or Motion 312 • Opposed the Order of Canada for Dr. Henry Morgentaler in 2008 • Made public anti-choice or “pro-life” statements • Participated publicly in anti-choice events or campaigns • Rated as “pro-life” (green) by Campaign Life Coalition ***Pro-choice MPs: Estimate includes Conservative MPs with a public pro-choice position and/or pro-choice voting record. It also includes all Liberal MPs except the anti-choice or indeterminate ones, and all MPs from all other parties based on the assumption they are pro-choice or will vote pro-choice. -

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for February 8Th, 2019

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for February 8th, 2019 To see what we've added to the Electric Scotland site view our What's New page at: http://www.electricscotland.com/whatsnew.htm To see what we've added to the Electric Canadian site view our What's New page at: http://www.electriccanadian.com/whatsnew.htm For the latest news from Scotland see our ScotNews feed at: https://electricscotland.com/scotnews.htm Electric Scotland News Looks like the BBC can no longer claim that their reporting is impartial. In fact I'm of the opinion that the BBC are actually anti-British. I can't actually understand why people being interviewed by their journalists are not hitting back at them. In many instances they are very rude to people that don't accept their views which on the whole are counter to the majority of their viewers. It's time that a proper investigation is done on the BBC reporting of Brexit While I am thoroughly fed up with Brexit and wish we'd just leave with a "No Deal" and get on with it I am also of the opinion that reporting on Trump is just as bad. I can see how the news media are so fascinated with Trump that they also think everyone else is as well. Well I have to say that the news media on the whole is so out of touch with ordinary people that they have become increasingly irrelevant to people in general. It was reported that in America most people get to learn the news through a comedy program.