Medieval Dynasties in Medieval Studies: a Historiographic Contribution*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles V, Monarchia Universalis and the Law of Nations (1515-1530)

+(,121/,1( Citation: 71 Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis 79 2003 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Mon Jan 30 03:58:51 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information CHARLES V, MONARCHIA UNIVERSALIS AND THE LAW OF NATIONS (1515-1530) by RANDALL LESAFFER (Tilburg and Leuven)* Introduction Nowadays most international legal historians agree that the first half of the sixteenth century - coinciding with the life of the emperor Charles V (1500- 1558) - marked the collapse of the medieval European order and the very first origins of the modem state system'. Though it took to the end of the seven- teenth century for the modem law of nations, based on the idea of state sover- eignty, to be formed, the roots of many of its concepts and institutions can be situated in this period2 . While all this might be true in retrospect, it would be by far overstretching the point to state that the victory of the emerging sovereign state over the medieval system was a foregone conclusion for the politicians and lawyers of * I am greatly indebted to professor James Crawford (Cambridge), professor Karl- Heinz Ziegler (Hamburg) and Mrs. Norah Engmann-Gallagher for their comments and suggestions, as well as to the board and staff of the Lauterpacht Research Centre for Inter- national Law at the University of Cambridge for their hospitality during the period I worked there on this article. -

Europa Regina. 16Th Century Maps of Europe in the Form of a Queen Europa Regina

Belgeo Revue belge de géographie 3-4 | 2008 Formatting Europe – Mapping a Continent Europa Regina. 16th century maps of Europe in the form of a queen Europa Regina. Cartes d’Europe du XVIe siècle en forme de reine Peter Meurer Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/belgeo/7711 DOI: 10.4000/belgeo.7711 ISSN: 2294-9135 Publisher: National Committee of Geography of Belgium, Société Royale Belge de Géographie Printed version Date of publication: 31 December 2008 Number of pages: 355-370 ISSN: 1377-2368 Electronic reference Peter Meurer, “Europa Regina. 16th century maps of Europe in the form of a queen”, Belgeo [Online], 3-4 | 2008, Online since 22 May 2013, connection on 05 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/belgeo/7711 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.7711 This text was automatically generated on 5 February 2021. Belgeo est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Europa Regina. 16th century maps of Europe in the form of a queen 1 Europa Regina. 16th century maps of Europe in the form of a queen Europa Regina. Cartes d’Europe du XVIe siècle en forme de reine Peter Meurer 1 The most common version of the antique myth around the female figure Europa is that which is told in book II of the Metamorphoses (“Transformations”, written around 8 BC) by the Roman poet Ovid : Europa was a Phoenician princess who was abducted by the enamoured Zeus in the form of a white bull and carried away to Crete, where she became the first queen of that island and the mother of the legendary king Minos. -

Imperial Ladies of the Ottonian Dynasty: Women and Rule in Tenth-Century Germany

2019 VI Imperial Ladies of the Ottonian Dynasty: Women and Rule in Tenth-Century Germany Phyllis G. Jestice New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018 Review by: Fraser McNair Review by: Agata Zielinska Review: Imperial Ladies of the Ottonian Dynasty: Women and Rule in Tenth-Century Germany Imperial Ladies of the Ottonian Dynasty: Women and Rule in Tenth-Century Germany. By Phyllis G. Jestice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. ISBN 978-3-319- 77305-6. xi+300 pp. £79.99. ne of the questions Phyllis Jestice confronts in her new book on the Ottonian rulers Adelaide and Theophanu is whether or not the tenth century was a ‘golden age’ for women. Certainly, we are O at the moment living through a golden age in the study of tenth- century women, and particularly of Ottonian queenship. Imperial Ladies of the Ottonian Dynasty is the third major English-language monograph on Ottonian queens to be released in the last two years. This interest is very welcome: as Jestice notes, these are not works of ‘women’s history,’ but studies of political history that focus on some of the most important European figures of their times. Given how many mysteries remain about theories and practices of tenth-century government, this is self-evidently worthwhile. Jestice concentrates on Empresses Adelaide and Theophanu. After the unexpected death of Otto II, these empresses were able to beat out the young emperor Otto III’s cousin Henry of Bavaria and successfully act as regents during the 980s and 990s, despite Henry’s seemingly overwhelming initial advantages in competing for the position. -

Names of Saints and Dynastic Name-Giving in Hungary in the 10-14Th Centuries in a Central and Eastern European Context1

Names of saints and dynastic name-giving in Hungary in the 10-14th centuries in a central and eastern European context1 Mariann SLÍZ Introduction: the relevance of investigating dynastic name-giving In this paper, I will survey the fairly complex relationship between medieval cults of saints and name-giving in royal dynasties in the Mid- dle Ages. However, before descending to particulars, I ought to account for the onomastic value of the investigation of this topic and for the use of the term dynastic naming or name-giving by emphasizing two obser- vations. Firstly, there are unambiguous differences between the name stocks of dynasties and the name stocks of the whole population of their countries; and secondly, there are unequivocal similarities in the naming practices of different dynasties. These two facts make name-giving in royal houses a special phenomenon. Although dynastic naming is con- fined only to a narrow stratum of the society, the differences and simi- larities between the name-giving practises of royal families and of their peoples may deserve the attention of onomasticians. As for the differences between the name stocks of the dynasties and of the populations, we can mention the names Farkas (‘Wolf’), Jakab (‘Jacob’), János (‘John’) and Miklós (‘Nicholas’) from Medi- eval Hungary. While they were amongst the most popular names in the 11-13th century in the whole population (cf. Benkő 1950, p. 23), none of them appeared in the name stock of the House of the Árpáds. The inverse of this phenomenon can also be observed: while the names Charles and Louis were frequent among the Anjous of Naples and of Hungary, Károly (‘Charles’) and Lajos (‘Louis’) were extraor- dinarily rare in the Angevin Age in Hungary (14th century).2 1 This paper was supported by the Bolyai János Research Scholarship of the Hun- garian Academy of Sciences. -

Itinerant Court Fürsten (Princes) Charlemagne Golden Bull of 1356

„Textura – Telling History“ Content card: „Middle Ages - Reign“ • the oldest known dynasty of the Franks • ruled from the early 5th to the middle of the 8th century Merovingian dynasty • issued by the Imperial Diet in 1356 • fixed the structure of the Roman Holy Empire, the role of the king and the prince-electors • in force until 1806 Golden Bull of 1356 • born in 747/748 • in 768 King of the Franks • 25.12.800 Pope Leo III crowned him Imperator Romanorum • died in 814 • had 1 son: Louis the Pious Charlemagne • highest nobility who ruled over states of the Holy Roman Empire • by the late Middle Ages some became sovereign rulers of an Imperial State that held imperial immediacy within the boundaries of the Holy Roman Empire of the Fürsten (princes) German Nation • The Kings and Emperors in the Holy Roman Empire had no capital but traveled with their family and court • Royal palaces and monasteries were used as accomodation. Itinerant Court CC BY SA : Ronald Hild / Daniel Bernsen • collection of Germanic peoples • originated in the lands between the Lower and Middle Rhine in the 3rd century AD • Frank means originally „free“, „fierce“ or „bold“ Franks • conflict between spiritual and secular power about who has the right to appoint clerics • between 1076 and 1122 Investiture controversy • Frankish noble family • Kings from 751 • name based on the Latin form of the name Karl (Karolus) Carolingian dynasty • Saxon noble family • Kings between 919 - 1024 • renewal of the translatio imperii by Otto I Ottonian dynasty • Restitutio imperii • The -

Redalyc.CRUSADING and MATRIMONY in the DYNASTIC

Byzantion Nea Hellás ISSN: 0716-2138 [email protected] Universidad de Chile Chile BARKER, JOHN W. CRUSADING AND MATRIMONY IN THE DYNASTIC POLICIES OF MONTFERRAT AND SAVOY Byzantion Nea Hellás, núm. 36, 2017, pp. 157-183 Universidad de Chile Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=363855434009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BYZANTION NEA HELLÁS Nº 36 - 2017: 157 / 183 CRUSADING AND MATRIMONY IN THE DYNASTIC POLICIES OF MONTFERRAT AND SAVOY JOHN W. BARKER UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON. U.S.A. Abstract: The uses of matrimony have always been standard practices for dynastic advancement through the ages. A perfect case study involves two important Italian families whose machinations had local implications and widespread international extensions. Their competitions are given particular point by the fact that one of the two families, the House of Savoy, was destined to become the dynasty around which the Modern State of Italy was created. This essay is, in part, a study in dynastic genealogies. But it is also a reminder of the wide impact of the crusading movements, beyond military operations and the creation of ephemeral Latin States in the Holy Land. Keywords: Matrimony, Crusading, Montferrat, Savoy, Levant. CRUZADA Y MATRIMONIO EN LAS POLÍTICAS DINÁSTICAS DE MONTFERRATO Y SABOYA Resumen: Los usos del matrimonio siempre han sido las prácticas estándar de ascenso dinástico a través de los tiempos. -

Timeline / 500 to 1100 / ALL COUNTRIES

Timeline / 500 to 1100 / ALL COUNTRIES Date Country | Description 502 A.D. Syria A treaty is made between the Roman Empire and the Ghassanids, a Christian Arab tribe settled in southern Syria and Damascus, in order to defend the eastern frontiers against the Persians. 507 A.D. Spain Visigoths defeated by the Franks at the Battle of Vouillé; collapse of the Visigoth Kingdom of Tolosa and withdrawal to the Iberian Peninsula (Kingdom of Toledo). 511 A.D. France Death of Clovis, the Merovingian king who converted to Catholicism, won control of most of the Frankish kingdoms and took Aquitaine from the Visigoths. 521 A.D. Sweden Rumour has it that in this year King Hugleikr, possibly from what is Sweden today, was slain with all his men in Friesland by the Frankish, i.e. Merovingian, Prince Theodebert. 527 A.D. Egypt Byzantine Emperor Justinian orders the construction of St. Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mount Moses in Central Sinai. It became the third pilgrimage site after Jerusalem and Rome. 527 A.D. Palestine* Justinian, the Byzantine Emperor, begins constructing many castles along the main caravan routes, and several churches in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Gaza and Nabatian Negev. 527 A.D. Italy Justinian (527–65) becomes the Emperor of Byzantium and sets about reconquering the West, succeeding in destroying the Gothic Kingdom in Italy. 528 A.D. Jordan The Byzantine Emperor Justinianus (later Justinian) grants the ally of the Byzantines, al-Haritha ibn Jibla, the Arab-Christian ruler of the Ghassan tribe who settled in Syria and Jordan, the title ‘Baselues’ (king). -

Asty at the Battle of Tours and Poitiers (Southern France) Over Arab Insurgents Leads to Their Retreat to the Southern Valley of the Rhone

Timeline / 700 to 1200 / GERMANY Date Country | Description 732 A.D. Germany Victory of Charles Martel (688–741) of the Carolingian Dynasty at the battle of Tours and Poitiers (southern France) over Arab insurgents leads to their retreat to the southern valley of the Rhone. 768 A.D. Germany Charlemagne (r. 768–814) inherits the Frankish crown and becomes king of a large part of Europe and the founder of a Roman, Christian and Germanic empire. 800 A.D. Germany King Charlemagne (768–814) is crowned as emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III (795–816). 814 A.D. Germany Charlemagne dies in Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) on 28 January 814 and is buried in the palatine chapel of Aachen. 843 A.D. Germany In the Treaty of Verdun the Frankish Empire is divided into three separate parts called West-, Middle- and East Francia. The Germanic Empire is called the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. 870 A.D. Germany In the Treaty of Mersen the Frankish Empire is divided into three separate parts. The empire of King Ludwig II (843–76) of the Carolingian Dynasty is enlargened. 911 A.D. Germany King Konrad I (911–18) of the Conradine Dynasty becomes king. 920 A.D. Germany Under Duke Henry of Saxony the term ‘Kingdom of the Germans’ (Regnum teutonicum) is used for the first time. 962 A.D. Germany On 2 February King Otto I (r. 936–73) of the Ottonian Dynasty, later called Otto the Great, is crowned emperor in Rome. 972 A.D. Germany King Otto II (r. -

The Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand Manuscript Fragment (MS L): New Evidence Concerning Luther, the Poet, and Ottonian Heritage

The Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand manuscript fragment (MS L): New evidence concerning Luther, the poet, and Ottonian heritage by Timothy Blaine Price A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Irmengard Rauch, Chair Professor Thomas F. Shannon Professor John Lindow Spring 2010 The Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand manuscript fragment (MS L): New evidence concerning Luther, the poet, and Ottonian heritage © 2010 by Timothy Blaine Price Abstract The Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand manuscript fragment (MS L): New evidence concerning Luther, the poet, and Ottonian heritage by Timothy Blaine Price Doctor of Philosophy in German University of California, Berkeley Professor Irmengard Rauch, Chair Begun as an investigation of the linguistic and paleographic evidence on the Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand fragment, the dissertation encompasses three analyses spanning over a millennium of that manuscript’s existence. First, a direct analysis clarifies errors in the published transcription (4.2). The corrections result from digital imaging processes (2.3) which reveal scribal details that are otherwise invisible. A revised phylogenic tree (2.2) places MS L as the oldest extant Heliand document. Further buoying this are transcription corrections for all six Heliand manuscripts (4.1). Altogether, the corrections contrast with the Old High German Tatian’s Monotessaron (3.3), i.e. the poet’s assumed source text (3.1). In fact, digital analysis of MS L reveals a small detail (4.2) not present in the Tatian text, thus calling into question earlier presumptions about the location and timing of the Heliand’s creation (14.4). -

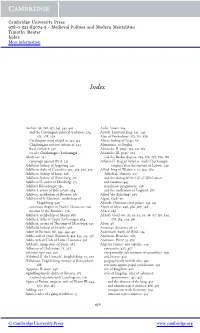

Medieval Polities and Modern Mentalities Timothy Reuter Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82074-5 - Medieval Polities and Modern Mentalities Timothy Reuter Index More information Index Aachen: 96, 128, 137, 145, 343, 425 Airlie, Stuart: 224 and the Carolingian political tradition: 274, Aistulf, Lombard king: 232, 242 275, 278, 279 Alan of Tewkesbury: 171, 172, 176 Carolingian royal chapel at: 141, 142 Albert, bishop of Liege:` 66 Charlemagne receives tribute at: 234 Alemannia: see Swabia fiscal complex: 337 Alexander II, pope: 150, 151, 162 see also Charlemagne; Lotharingia Alexander III, pope: 204 Abodrites: 232 and the Becket dispute: 174, 176, 177, 180, 186 campaign against (892): 221 Alfonso II, king of Asturias: sends Charlemagne Adalbero, bishop of Augsburg: 225 trophies after the capture of Lisbon: 240 Adalbero, duke of Carinthia: 202, 363, 372, 379 Alfred, king of Wessex: 5, 15, 140, 280 Adalbero, bishop of Laon: 228 ‘Alfredian’ charters: 297 Adalbero, bishop of Wurtzburg:¨ 371 and the dating of the Life of Alfred: 10–11 Adalbero II, count of Ebersberg: 375 and taxation: 445 Adalbert Babenberger: 114 translation programme: 298 Adalbert, count of Ballenstedt: 364 and the unification of England: 287 Adalbert, archbishop of Bremen: 385 Alfred ‘the Ætheling’: 290 Adalbert of St Maximin, archbishop of Algazi, Gadi: 115 Magdeburg: 340 Allstedt, Ottonian royal palace: 141, 142 continues Regino of Prum’s¨ Chronicon: 290 Alpert of Metz: 146, 366, 367, 398 mission to the Russians: 276 Alsace: 286 Adalbert, archbishop of Mainz: 380 Althoff, Gerd: 90, 91, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 130, 144, Adalbert, -

Kievan Rus' in the Medieval World

Harvard Historical Studies • 177 Published under the auspices of the Department of History from the income of the Paul Revere Frothingham Bequest Robert Louis Stroock Fund Henry Warren Torrey Fund Reimagining Europe Kievan Rus in the Medieval World Christian Raff ensperger Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2012 Copyright © 2012 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Raff ensperger, Christian. Reimagining Europe : Kievan Rus in the medieval world / Christian Raff ensperger. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 06384- 6 (alkaline paper) 1. Kievan Rus—History—862–1237. 2. Kievan Rus—Civilization—Byzantine infl uences. 3. Kievan Rus—Relations—Europe. 4. Europe—Relations— Kievan Rus . 5. Christianity— Kievan Rus. I. Title. DK73.R24 2012 947'.02—dc23 2011039243 For Cara Contents Introduction: Rethinking Rus 1 1 Th e Byzantine Ideal 10 2 Th e Ties Th at Bind 47 3 Rusian Dynastic Marriage 71 4 Kiev as a Center of Eu ro pe an Trade 115 5 Th e Micro- Christendom of Rus 136 Conclusion: Rus in a Wider World 186 Appendix: Rulers of Rus 191 Notes 193 Bibliography 283 A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s 323 Index 325 Reimagining Eu rope Introduction Rethinking Rus Students of history oft en begin by seeking “the facts,” a set of concrete pieces that will create an edifi ce of “truth” and thus an explanation. Th is is diffi cult to accomplish even for something as recent as World War II, much less an arena of study dealing with events that took place a thousand years ago. -

157 Crusading and Matrimony in the Dynastic Policies

BYZANTION NEA HELLÁS Nº 36 - 2017: 157 / 183 CRUSADING AND MATRIMONY IN THE DYNASTIC POLICIES OF MONTFERRAT AND SAVOY JOHN W. BARKER UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON. U.S.A. Abstract: The uses of matrimony have always been standard practices for dynastic advancement through the ages. A perfect case study involves two important Italian families whose machinations had local implications and widespread international extensions. Their competitions are given particular point by the fact that one of the two families, the House of Savoy, was destined to become the dynasty around which the Modern State of Italy was created. This essay is, in part, a study in dynastic genealogies. But it is also a reminder of the wide impact of the crusading movements, beyond military operations and the creation of ephemeral Latin States in the Holy Land. Keywords: Matrimony, Crusading, Montferrat, Savoy, Levant. CRUZADA Y MATRIMONIO EN LAS POLÍTICAS DINÁSTICAS DE MONTFERRATO Y SABOYA Resumen: Los usos del matrimonio siempre han sido las prácticas estándar de ascenso dinástico a través de los tiempos. Un caso de estudio perfecto implica a dos importantes familias italianas cuyas maquinaciones tenían implicaciones locales y extensiones internacionales generalizadas. Sus competencias tienen como punto particular el hecho de que una de las dos familias, la Casa de Saboya, estaba destinada a convertirse en la dinastía alrededor de la cual se creó el Estado Moderno de Italia. Este ensayo es, en parte, un estudio sobre genealogía dinástica. Pero también es un recordatorio de la gran repercusión de los movimientos cruzados, más allá de las operaciones militares y la creación de efímeros Estados Latinos en la Tierra Santa.