Flag Research Quarterly, May 2017, No. 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PWA Unity Diversity Publication July 2017

July 2017 Volume 1, Issue 3 Unity: Cultivating Diversity and Inclusion in PWA Hilo, Hawaii LGBT Film Screening Hilo, Hawaii recognized LGBT Month by holding a special screening of the film Limited Partnerships. Limited Partnership is the love story between Filipino-American Richard Adams and his Australian husband, Tony Sullivan. In 1975, thanks to a courageous county clerk in Boulder, CO, Richard and Tony were one of the first same-sex couples in the world to be legally married. Richard immediately filed for a green card for Tony based on their marriage. But unlike most heterosexual married couples who easily file petitions and obtain green cards, Richard received a denial letter from the Immi- gration and Naturalization Service stating, “You have failed to establish that a bona AREA DIRECTOR’S fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.” Outraged at the tone, tenor CORNER: and politics of this letter and to prevent Tony’s impending deportation, the couple sued the U.S. government. This became the first federal lawsuit seeking equal treat- Maintaining a workplace that wel- ment for a same-sex marriage in U.S. history. comes diversity in all forms is an im- Over four decades of legal challenges, Richard and Tony figured out how to maintain portant component of attracting high- ly-qualified applicants for our job their sense of humor, justice and whenever possible, their privacy. Their personal vacancies. Celebrations of Special tale parallels the history of the LGBT marriage and immigration equality move- Emphasis Program months contribute ments, from the couple signing their marriage license in Colorado, to the historic to this effort by enhancing our appre- U.S. -

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk Riya Kalra Junior Division Individual Exhibit Student-composed words: 499 Process paper: 500 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Black, Jason E., and Charles E. Morris, compilers. An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk's Speeches and Writings. University of California Press, 2013. This book is a compilation of Harvey Milk's speeches and interviews throughout his time in California. These interviews describe his views on the community and provide an idea as to what type of person he was. This book helped me because it gave me direct quotes from him and allowed me to clearly understand exactly what his perspective was on major issues. Board of Supervisors in January 8, 1978. City and County of San Francisco, sfbos.org/inauguration. Accessed 2 Jan. 2019. This image is of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from the time Harvey Milk was a supervisor. This image shows the people who were on the board with him. This helped my project because it gave a visual of many of the key people in the story of Harvey Milk. Braley, Colin E. Sharice Davids at a Victory Party. NBC, 6 Nov. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/sharice-davids-lesbian-native-american-makes- political-history-kansas-n933211. Accessed 2 May 2019. This is an image of Sharcie Davids at a victory party after she was elected to congress in Kansas. This image helped me because ti provided a face to go with he quote that I used on my impact section of board. California State, Legislature, Senate. Proposition 6. -

Part II: Creating a Welcoming and Safe Environment for LGBT People and Families Glgeneral Hkihousekeeping

Quality Healthcare for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender People A Four‐Part Webinar Series Part II: Creating a Welcoming and Safe Environment for LGBT People and Families GlGeneral HkiHousekeeping • If you experience any technical difficulties during the webinar, please contact GoToMeetinggpp.com Customer Support at: 1-888-259-8414 or 1-805-617-7002 About Us “Exploration and Intervention for Health Equality…” Designated a “National Center of Excellence” by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Cultural Competency Organizational Assessment-360 (COA360) COA360 TM http://www.coa360 .org Culture Quality Collaborative (CQC) http://www.thecqc .org About GLMA www.glma.org GLMA works to ensure equality in healthcare for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals and healthcare professionals. Multidisciplinary membership Patient Resources: Provider Directory “Top Ten Things to Discuss with your Provider” GLMA holds a national, scientific health conference each year (Save-the-Date: Sept. 18-21, 2013 in Denver, CO) Soon-to-be-Released: GLMAs GLMA’s Recommendations for LGBT Equity & Inclusion in Health Professions Education Webinar Series Faculty Today’s presenter: Nathan Levitt, RN Community Outreach and Education Nurse Callen‐Lorde Community Health Center 356 West 18th Street, New York, NY 10011 www.callen‐lorde.org 7 Learning Objectives By the end of this webinar, participants will be able to: • Describe barriers faced by LGBT people in accessing healthcare and why these -

Bdsm) Communities

BOUND BY CONSENT: CONCEPTS OF CONSENT WITHIN THE LEATHER AND BONDAGE, DOMINATION, SADOMASOCHISM (BDSM) COMMUNITIES A Thesis by Anita Fulkerson Bachelor of General Studies, Wichita State University, 1993 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Anita Fulkerson All Rights Reserved Note that thesis work is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. Only the author has the legal right to publish, produce, sell, or distribute this work. Author permission is needed for others to directly quote significant amounts of information in their own work or to summarize substantial amounts of information in their own work. Limited amounts of information cited, paraphrased, or summarized from the work may be used with proper citation of where to find the original work. BOUND BY CONSENT: CONCEPTS OF CONSENT WITHIN THE LEATHER AND BONDAGE, DOMINATION, SADOMASOCHISM (BDSM) COMMUNITIES The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies _______________________________________ Ron Matson, Committee Chair _______________________________________ Linnea Glen-Maye, Committee Member _______________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member _______________________________________ Patricia Phillips, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my Ma'am, my parents, and my Leather Family iv When you build consent, you build the Community. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my adviser, Ron Matson, for his unwavering belief in this topic and in my ability to do it justice and his unending enthusiasm for the project. -

Wignall, Liam (2018) Kinky Sexual Subcultures and Virtual Leisure Spaces. Doctoral Thesis, University of Sunderland

Wignall, Liam (2018) Kinky Sexual Subcultures and Virtual Leisure Spaces. Doctoral thesis, University of Sunderland. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/8825/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Kinky Sexual Subcultures and Virtual Leisure Spaces Liam Wignall A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Sunderland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2018 i | P a g e Abstract This study seeks to understand what kink is, exploring this question using narratives and experiences of gay and bisexual men who engage in kink in the UK. In doing so, contemporary understandings of the gay kinky subcultures in the UK are provided. It discusses the role of the internet for these subcultures, highlighting the use of socio-sexual networking sites. It also recognises the existence of kink dabblers who engage in kink activities, but do not immerse themselves in kink communities. A qualitative analysis is used consisting of semi-structured in-depth interviews with 15 individuals who identify as part of a kink subculture and 15 individuals who do not. Participants were recruited through a mixture of kinky and non-kinky socio-sexual networking sites across the UK. Complimenting this, the author attended kink events throughout the UK and conducted participant observations. The study draws on subcultural theory, the leisure perspective and social constructionism to conceptualise how kink is practiced and understood by the participants. It is one of the first to address the gap in the knowledge of individuals who practice kink activities but who do so as a form of casual leisure, akin to other hobbies, as well as giving due attention to the increasing presence and importance of socio-sexual networking sites and the Internet more broadly for kink subcultures. -

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Identity Formation Michele J

1 Shifting Sands or Solid Foundation? Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Identity Formation Michele J. Eliason and Robert Schope 1 Introduction How do some individuals come to identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender? Is there a static, universal process of identity formation that crosses all lines of individual difference, such as sexual identities, sex/gender, class, race/ethnicity, and age? If so, can we describe that process in a series of linear stages or steps? Is identity based on a rock-solid foundation, stable and consistent over time? Or are there many identity formation processes that are specific to social and historical factors and/or individual differences, an ever- shifting landscape like a sand dune? The field of lesbian/gay/ bisexual/transgender (LGBT) studies is characterized by competing paradigms expressed in various ways: nature versus nurture, biology versus environment, and essentialism versus social constructionism (Eliason, 1996b). Although subtly different, all three debates share common features. Nature, biology, and essentialistic paradigms propose that sexual and gender identities are “real,” based in biology or very early life experiences and fixed and stable throughout the life span. These paradigms allow for the development of linear stages of development, or “coming out,” models. On the other hand, nurture, environment, and social constructionist paradigms point to sexual and gender identities as contingent on time and place, social circumstances, and historical period, thus suggesting that identities are flexible, vari- able, and mutable. “Queer theory” conceptualizations of gender and sexuality as fluid, “performative,” and based on social-historical con- texts do not allow for neat and tidy stage theories of identity develop- ment. -

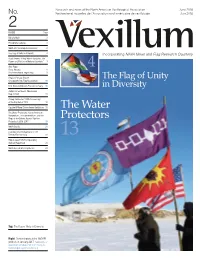

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Pride Politics: a Socio-Affective Analysis by Randi Nixon a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For

Pride Politics: A Socio-Affective Analysis by Randi Nixon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Alberta ©Randi Nixon, 2017 ii Abstract: This dissertation explores the affective politics of pride in the context of neoliberalism and the multitude of way that proud feelings map onto issues of social justice. Since pride is so varied in both its individual and political manifestations, I draw on numerous instances of collective pride to attend to the relational, structural and historical contours of proud feelings. Given the methodological challenges posed by affect, I use a mixed- method approach that includes interviews, participant observation, and discourse analysis, while being keenly attuned to the tension between bodily materiality and discursivity. Each chapter attends to an “event” of pride, exploring its emergence during particular encounters with collective difference. The project fills a gap in affect theory by attending to the way that proud feelings play a vital role in both igniting the political intensity necessary to bring about change (through Pride politics), and blocking or extinguishing possibilities of respectful dialogue and solidarity across gendered, sexual, and racial difference. Across the chapters, pride is used as a conduit through which the complexity of affective politics can be examined. The proud events around and through which each chapter is structured expose paths of affect and its politics. Taken together, the chapters provide an initial blueprint for navigating contemporary affective politics. Through an examination of the discursive rendering of pride, I find that, across several literatures, two key characteristics of pride are its deep relationality between individuals and collectives, and the way it circulates, is managed, and emerges in relation to social hierarches and the value attached to political categories (race, class, gender, ability). -

Commission Report Final UK

JOINT COMMISSION ON VEXILLOGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES of The Flag Institute and North American Vexillological Association ! ! THE COMMISSION’S REPORT ON THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES OF FLAG DESIGN 1st October 2014 These principles have been adopted by The Flag Institute and North American Vexillological Association | Association nord-américaine de vexillologie, based on the recommendations of a Joint Commission convened by Charles Ashburner (Chief Executive, The Flag Institute) and Hugh Brady (President, NAVA). The members of the Joint Commission were: Graham M.P. Bartram (Chairman) Edward B. Kaye Jason Saber Charles A. Spain Philip S. Tibbetts Introduction This report attempts to lay out for the public benefit some basic guidelines to help those developing new flags for their communities and organizations, or suggesting refinements to existing ones. Flags perform a very powerful function and this best practice advice is intended to help with optimising the ability of flags to fulfil this function. The principles contained within it are only guidelines, as for each “don’t do this” there is almost certainly a flag which does just that and yet works. An obvious example would be item 3.1 “fewer colours”, yet who would deny that both the flag of South Africa and the Gay Pride Flag work well, despite having six colours each. An important part of a flag is its aesthetic appeal, but as the the 18th century Scottish philosopher, David Hume, wrote, “Beauty in things exists merely in the mind which contemplates them.” Different cultures will prefer different aesthetics, so a general set of principles, such as this report, cannot hope to cover what will and will not work aesthetically. -

Safe Zone Manual – Edited 9.15.2015 1

Fall 2015 UCM SAFE ZONE GUIDE FOR ALLIES UCM – Safe Zone Manual – Edited 9.15.2015 1 Contents Safe Zone Program Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Terms, Definitions, and Labels ................................................................................................................. 6 Symbols and Flags................................................................................................................................... 19 Gender Identity ......................................................................................................................................... 24 What is Homophobia? ............................................................................................................................. 25 Biphobia – Myths and Realities of Bisexuality ..................................................................................... 26 Transphobia- Myths & Realities of Transgender ................................................................................. 28 Homophobia/biphobia/transphobia in Clinical Terms: The Riddle Scale ......................................... 30 How Homophobia/biphobia/transphobia Hurts Us All......................................................................... 32 National Statistics and Research Findings ........................................................................................... 33 Missouri State “Snapshot” ...................................................................................................................... -

The Role of the United Nations in Combatting Discrimination and Violence Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People

The Role of the United Nations in Combatting Discrimination and Violence against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People A Programmatic Overview 19 June 2018 This paper provides a snapshot of the work of a number of United Nations entities in combatting discrimination and violence based on sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics and related work in support of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) and intersex communities around the world. It has been prepared by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on the basis of inputs provided by relevant UN entities, and is not intended to be either exhaustive or detailed. Given the evolving nature of UN work in this field, it is likely to benefit from regular updating1. The final section, below, includes a Contact List of focal points in each UN entity, as well as links and references to documents, reports and other materials that can be consulted for further information. Click to jump to: Joint UN statement, OHCHR, UNDP, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO, the World Bank, IOM, UNAIDS (the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS), UNRISD and Joint UN initiatives. Joint UN statement Joint UN statement on Ending violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people: o On 29 September 2015, 12 UN entities (ILO, OHCHR, UNAIDS Secretariat, UNDP, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNODC, UN Women, WFP and WHO) released an unprecedented joint statement calling for an end to violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people. o The statement is a powerful call to action to States and other stakeholders to do more to protect individuals from violence, torture and ill-treatment, repeal discriminatory laws and protect individuals from discrimination, and an expression of the commitment on the part of UN entities to support Member States to do so. -

Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race the Opportunity Agenda

Opinion Research & Media Content Analysis Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race The Opportunity Agenda Acknowledgments This research was conducted by Loren Siegel (Executive Summary, What Americans Think about LGBT People, Rights and Issues: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Public Opinion, and Coverage of LGBT Issues in African American Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); Elena Shore, Editor/Latino Media Monitor of New America Media (Coverage of LGBT Issues in Latino Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); and Cheryl Contee, Austen Levihn- Coon, Kelly Rand, Adriana Dakin, and Catherine Saddlemire of Fission Strategy (Online Discourse about LGBT Issues in African American and Latino Communities: An Analysis of Web 2.0 Content). Loren Siegel acted as Editor-at-Large of the report, with assistance from staff of The Opportunity Agenda. Christopher Moore designed the report. The Opportunity Agenda’s research on the intersection of LGBT rights and racial justice is funded by the Arcus Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are those of The Opportunity Agenda. Special thanks to those who contributed to this project, including Sharda Sekaran, Shareeza Bhola, Rashad Robinson, Kenyon Farrow, Juan Battle, Sharon Lettman, Donna Payne, and Urvashi Vaid. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works with social justice groups, leaders, and movements to advance solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and corresponding solutions; uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives.