Loudoun County African-American Historic Architectural Resources Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Nomination Form, 1983]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3443/nomination-form-1983-43443.webp)

Nomination Form, 1983]

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) VvvL ~Jtf;/~ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service !VfH-f G"/;<-f/q NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ============================================================================================== 1. Name of Property ============================================================================================== historic name Bear's Den Rural Historic District other names/site number VDHR File No. 021-6010 ============================================================================================== 2. Location ============================================================================================== street & number Generally runs along both sides of ridge along parts of Raven Rocks and Blue Ridge Mtn Rds, extends down Harry -

Loudoun County African-American Historic Architectural Resources Survey

Loudoun County African-American Historic Architectural Resources Survey Lincoln "Colored" School, 1938. From the Library of Virginia: School Building Services Photograph Collection. Prepared by: History Matters, LLC Washington, DC September 2004 Sponsored by the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors & The Black History Committee of the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library Leesburg, VA Loudoun County African-American Historic Architectural Resources Survey Prepared by: Kathryn Gettings Smith Edna Johnston Megan Glynn History Matters, LLC Washington, DC September 2004 Sponsored by the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors & The Black History Committee of the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library Leesburg, VA Loudoun County Department of Planning 1 Harrison Street, S.E., 3rd Floor Leesburg, VA 20175 703-777-0246 Table of Contents I. Abstract 4 II. Acknowledgements 5 III. List of Figures 6 IV. Project Description and Research Design 8 V. Historic Context A. Historic Overview 10 B. Discussion of Surveyed Resources 19 VI. Survey Findings 56 VII. Recommendations 58 VIII. Bibliography 62 IX. Appendices A. Indices of Surveyed Resources 72 B. Brief Histories of Surveyed Towns, Villages, Hamlets, 108 & Neighborhoods C. African-American Cemeteries in Loudoun County 126 D. Explanations of Historic Themes 127 E. Possible Sites For Future Survey 130 F. Previously Documented Resources with Significance to 136 Loudoun County’s African-American History 1 Figure 1: Map of Loudoun County, Virginia with principal roads, towns, and waterways. Map courtesy of the Loudoun County Office of Mapping. 2 Figure 2. Historically African-American Communities of Loudoun County, Virginia. Prepared by Loudoun County Office of Mapping, May 15, 2001 (Map #2001-015) from data collected by the Black History Committee of the Friends of Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Va. -

Portraits of African Americans Who Made a Difference in Loudoun County, Virginia

The Black History Committee, Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. The Essence of a People: Portraits of African Americans Who Made a Difference in Loudoun County, Virginia. Leesburg, Virginia: Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, 2001. The Black History Committee, Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. The Essence of a People II: African- Americans Who Made Their Worlds Anew in Loudoun County, and Beyond. Kendra Y. Hamilton, editor. Leesburg, Virginia Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, 2002. Duncan, Patricia B. Abstracts of Loudoun County, Virginia Register of Free Negroes, 1844-1861. Westminster, Maryland, 2000. Guild, June Purcell. Black Laws of Virginia. [For the Afro-American Historical Association], Lovettsville, Virginia: Willow Bend Books, 1996. Janney, Asa Moore, and Werner Janney. Ye Meeting Hous Smal. Lincoln, Virginia, 1980. Lee, Deborah A. Loudoun County’s African American Communities: A Tour Map and Guide. Leesburg, Virginia: The Black History Committee, Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, 2004. Michael, Jerry. Back to the 1870s: Items of Interest from the Local Press. [Draft]. Leesburg, Virginia, 2004. Michael, Jerry. The Year After: Selections from the Democratic Mirror, June 14, 1865- June 13, 1866. Leesburg, Virginia, 1996. Poland, Charles. From Frontier to Suburbia. Marceline, Missouri: Walsworth Publishing, 1976. Record of Free Negroes. Leesburg, Virginia: The Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court. Reid, Frances H. Inside Loudoun: The Way It Was. Leesburg, Virginia: Loudoun Times- Mirror, 1986. Souders, Bronwen C. and John M. A Rock in a Weary Land, A Shelter in a Time of Storm: African-American Experience in Waterford, Virginia. Waterford, Virginia: Waterford Foundation, 2003. Thompson, Elaine and Betty Morefield. -

A Guide to the African American Heritage of Arlington County, Virginia

A GUIDE TO THE AFRICAN AMERICAN HERITAGE OF ARLINGTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY PLANNING, HOUSING AND DEVELOPMENT HISTORIC PRESERVATION PROGRAM SECOND EDITION 2016 Front and back covers: Waud, Alfred R. "Freedman's Village, Greene Heights, Arlington, Virginia." Drawn in April 1864. Published in Harper's Weekly on May 7, 1864. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Table of Contents Discover Arlington's African American Heritage .......................... iii Lomax A.M.E. Zion Church & Cemetery .......................... 29 Mount Zion Baptist Church ................................................ 30 Boundary Markers of the District of Columbia ............................ 1 Macedonia Baptist Church ................................................. 31 Benjamin Banneker ............................................................. 1 Our Lady, Queen of Peace Catholic Church .................... 31 Banneker Boundary Stone ................................................. 1 Establishment of the Kemper School ............................... 32 Principal Ella M. Boston ...................................................... 33 Arlington House .................................................................................. 2 Kemper Annex and Drew Elementary School ................. 33 George Washington Parke Custis ...................................... 2 Integration of the Drew School .......................................... 33 Custis Family and Slavery ................................................... 2 Head -

Geologic Map of the Loudoun County, Virginia, Part of the Harpers Ferry Quadrangle

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP MF-2173 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE LOUDOUN COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PART OF THE HARPERS FERRY QUADRANGLE By C. Scott Southworth INTRODUCTION Antietam Quartzite constituted the Chilhowee Group of Early Cambrian age. Bedrock and surficial deposits were mapped in 1989-90 as part For this report, the Loudoun Formation is not recognized. As of a cooperative agreement with the Loudoun County Department used by Nickelsen (1956), the Loudoun consisted primarily of of Environmental Resources. This map is one of a series of geologic phyllite and a local uppermost coarse pebble conglomerate. Phyl- field investigations (Southworth, 1990; Jacobson and others, lite, of probable tuffaceous origin, is largely indistinguishable in the 1990) in Loudoun County, Va. This report, which includes Swift Run, Catoctin, and Loudoun Formations. Phyl'ite, previously geochemical and structural data, provides a framework for future mapped as Loudoun Formation, cannot be reliably separated from derivative studies such as soil and ground-water analyses, which phyllite in the Catoctin; thus it is here mapped as Catoctin are important because of the increasing demand for water and Formation. The coarse pebble conglomerate previously included in because of potential contamination problems resulting from the the Loudoun is here mapped as a basal unit of the overlying lower recent change in land use from rural-agricultural to high-density member of the Weverton Formation. The contact of the conglom suburban development. erate and the phyllite is sharp and is interpreted to represent a Mapping was done on 5-ft-contour interval topographic maps major change in depositional environment. -

Collection SC 0151 Manassas Industrial School Fiftieth Anniversary Program 1945

Collection SC 0151 Manassas Industrial School Fiftieth Anniversary Program 1945 Table of Contents User Information Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Container List Processed by Laura Christiansen 23 March 2021 Thomas Balch Library 208 W. Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 USER INFORMATION VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 1 item COLLECTION DATES: 1945 PROVENANCE: Gift of Velma Dunnaville Leigh, Donated by Wilhelmina Leigh, Washington, DC. ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: Collection open for research. USE RESTRICTIONS: No physical characteristics affect use of this material. REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from Thomas Balch Library. CITE AS: Manassas Industrial School Fiftieth Anniversary Program, 1945 (SC 0151), Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. ALTERNATE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS: None RELATED HOLDINGS: Lewis, Stephen Johnson. 1994. Undaunted faith--: the life story of Jennie Dean: missionary, teacher, crusader, builder, founder of the Manassas Industrial School. V REF 921 DEAN JENNIE Sherry Zvares Sanabria, Settle-Dean Cabin, Acrylic on Museum Board, 2002 [Painting is in the Thomas Balch Library Collection] ACCESSION NUMBERS: 2019.0063 2 HISTORICAL SKETCH Jennie Serepta Dean (1848–1913) was the daughter of Charles W. Dean (born c. 1822) and Annie Stewart Dean (born c. 1826) of Loudoun County, Virginia. Enslaved, the Dean family lived in a cabin near the village of Conklin. Following Emancipation at the end of the Civil War, the family moved to Prince William County. After attending school, Jennie Dean worked as a domestic servant in Washington, DC while helping her sister attend school. Around 1878, Dean founded a Sunday school in Prince William County, and began traveling around the area providing religious instruction and education. -

Propane Costs Too Much!

STANDARD PRESORT RESIDENTIAL U.S. POSTAGE CUSTOMER PAID ECRWSS PERMIT NO. 82 WOODSTOCK, VA FEBRUARY 2019 www.blueridgeleader.com blueridgeleader SINCE 1984 ‘Personal Recreation Fields’ free to turn rural Loudoun into dumping grounds BY ANDREA GAINES In an impassioned letter dated Jan. 24, 2019, Cattail, LC, a limited partnership of family members who have over 800 acres of farmland under Nature Conservancy easement outside of Hamilton, showed the Board of Supervisors the necessity of dealing with an almost wholly unregulated landfill approved by the County. The letter was accompanied by a stun- ningly raw video showing what can only be described as massive landfill activity, “mas- Loudoun, show your querading,” says the partnership, as what is known as a “Personal Recreational Field.” love for Cannons That field is, in fact, an 18-acre tract of land – 30 feet high in some places – and strewn Aerial photos, video, and an explanation baseball; Team seeks of the case can be seen at www. with piles of dirt, massive chunks of con- LoudounRuralLandFills.com. host families crete and asphalt, construction debris, plas- For a copy of the Cattail, LC “Open Letter tic waste, and, in some places, liquid waste. to The Board of Supervisors, Jan. 24, BY ANDREA GAINES The waste is brought in by large dump 2019,” go to BlueRidgeLeader.com. The opening of the baseball season trucks accessing the site from old Business is some months away, but the Can- nons organization is working hard 7. The trucks enter – dozens and dozens per required to dispose of in a particular manner. -

Correspondences Received by DHR From: Marcia

Correspondences Received by DHR From: Marcia Cunningham <[email protected]> Date: Fri, Dec 18, 2020 at 8:22 AM Subject: Barbara Rose Johns sculptor? To: <[email protected]> My hometown of Auburn, New York is home to the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park. In 2019, a statue was unveiled in her honor at the NYS Equal Rights Heritage Center located next door to the William H. Seward House Museum in the heart of downtown. The Hanlon Sculpture Studio could be an excellent choice for the Barbara Rose Johns statue. https://www.localsyr.com/news/local-news/-10-million-auburn-welcome-center-opens-harriet- tubman-statue-unveiled/1594277038/ https://auburnpub.com/news/local/i-just-cant-wait-harriet-tubman-statue-commissioned-for- downtown-auburn-welcome-center/article_5f7bab19-0e81-5ab7-a47a-ea8e43fcadf3.html https://www.hanlonsculpture.com/ I highly support your choice of this amazing young woman—and have had the sobering privilege of visiting the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka, KS. Thank you. Marcia Cunningham Stephens City, VA From: Mary Johnston-Clark <[email protected]> Date: Mon, Dec 21, 2020 at 9:46 PM Subject: Call for artist for new UScapitol sculpture? To: <[email protected]> Dear US Capitol commission- I am interested in submitting my qualification for this commission. Can you please provide me with additional information? Thank you, David Alan Clark Www.DavidAlanClark.com From: Mary Johnston-Clark <[email protected]> Date: Mon, Dec 21, 2020 at 9:46 PM Subject: Call for artist for new UScapitol sculpture? To: <[email protected]> Dear US Capitol commission- I am interested in submitting my qualification for this commission. -

The Blackburn Murder the First Major Battle of the Civil War Daniel Morrow Earlier, Massie Handed His Hymnal to Her Condition

Printed using recycled fiber Tropical for Summer Page 15 Middleburg’s Only Locally Owned and Operated Newspaper Volume 8 Issue 4 www.mbecc.com July 28, 2011 ~ August 25, 2011 Middleburg Humane National Sporting Foundation Gala Page 18 Museum Sneak Preview ortunate Hunt Country pa- wing where every historic fireplace trons and supporters forgot mantle and wide-plank floor has the steamy July evening been impeccably restored. Atten- weather when they were tion to detail has been visibly and recently invited for cocktails and pleasantly the watchword through- Fa sneak preview of the National out. Sporting Library’s new Museum. “We are so proud of it,” Board The completely renovated Chairman Manley Johnson said. and expanded Vine Hill evoked an “The National Sporting Library extraordinary array of positive com- Board’s decision to expand into the ment and compliment as guests as- fine art field was made to help keep cended the limestone steps to enter the history and legacy of America’s the new wing. Crossing the airy great country life alive and well. We opening gallery, they went up the are immensely pleased to create this sweeping spiral staircase to beauti- museum for our community.” fully lit and appointed exhibit rooms In fact, the mission of the Nation- on the second floor. al Sporting Library and Museum, is to Designers and architects have ‘preserve and to share the art, literature created pristine new wing galleries, and culture of horse and field sports.’ welcoming and elegant, that inte- Located on the Library’s Middleburg, grate seamlessly with the renovated Continued Page 5 Historic Furr Farm Sesquicentennial Celebration Billie Van Pay ne of the most histor- ic farms in Loudoun County, the Furr-Leith Farm on Snickersville Turnpike, sold last year af- Oter having been owned by the Furr-Leith family for seven gen- erations. -

Department of Building and Development

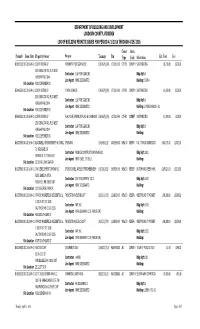

DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING AND DEVELOPMENT LOUDOUN COUNTY, VIRGINIA LOG OF BUILDING PERMITS ISSUED FOR PERIOD 4/1/2016 THROUGH 4/15/2016 Const Occu Permit# Issue Date Property OwnerPurpose Taxmap Pin Type Code Subdivision Est. Cost Fee B50465130100 2016-04-01 SOUTH RIDING LP MONUMENT FOR SIGN W/ELE 106/B67/////A/ 1271811540 OTHER COMOTHSOUTH RIDING $8,700.00 $330.00 250 GIBRALTAR RD, FL 3 WEST Contractor: CLAYTON SIGNS INC Bldg Sqft: 0 HORSHAM PA 19044 Lien Agent: NONE DESIGNATED Building: SIGN A Site Location 43310 DEFENDER DR B50465250100 2016-04-01 SOUTH RIDING LP 2 MENU BOARDS 106/B67/////A/ 1271811540 OTHER COMOTHSOUTH RIDING $5,000.00 $330.00 250 GIBRALTAR RD, FL 3 WEST Contractor: CLAYTON SIGNS INC Bldg Sqft: 0 HORSHAM PA 19044 Lien Agent: NONE DESIGNATED Building: 2 MENU BOARDS / H1 Site Location 43310 DEFENDER DR B50465620100 2016-04-01 SOUTH RIDING LP FLAG POLE (AMERICAN FLAG) & CLEARANCE 106/B67/////A/ 1271811540 OTHER COMRETSOUTH RIDING $1,000.00 $330.00 250 GIBRALTAR RD, FL 3 WEST Contractor: CLAYTON SIGNS INC Bldg Sqft: 0 HORSHAM PA 19044 Lien Agent: NONE DESIGNATED Building: Site Location 43310 DEFENDER DR B60272690100 2016-04-01 BLACKWELL, KEVIN KENNETH & CAMILL SFD/BARN /34//49/////2/ 6083039420 NEWCO RESSFDR & J TAYLOR SUBDIVISIO $416,173.00 $2,701.35 71 VERSHIRE CIR Contractor: PHOENIX CONSTRUCTION MANAG INC Bldg Sqft: 2901 MAGNOLIA TX 77354-3319 Lien Agent: FIRST EXCEL TITLE LLC Building: Site Location 35150 WILLIAMS GAP RD B60278560100 2016-04-01 DAY DEVELOPMENT COMPANY LC SFD/ROCKWELL W/ELEVC/FINISHEDBASE/4' //9//33////32/ -

The Loudoun County Fair Returns! July 28 - Aug 1

The Loudoun Fair Returns! Dear Catoctin Residents, This is the part of the year where many of us wonder, “Where did the summer go?” This year, though, I'm glad to add the thought, "But the Loudoun County Fair is back." The Loudoun Fair has been running continuously since 1936. Last year, COVID-19 forced them to take the event online, but now they are back in person. I can personally confirm that this year's Fair has been a blast. I've added a full article on it below, complete with plenty of photos. (And I'm telling you now, if you haven't seen the Pig Scramble yet, you're missing out.) Also, I just learned about another Loudoun history moment that is connected to July. This one took place during the French and Indian War, and I thought I'd share the story here. On July 9, 1755, British Major General Edward Braddock led a force of British regulars and American militia to be defeated by French forces near what is now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Things went so poorly that the incident is still commonly referred to as Braddock's Defeat. George Washington and Daniel Boone were both part of Braddock's force; both men survived the battle, and joined the rest of the force in swiftly departing back down the road they had built through the Appalachian Mountains. Here's the Loudoun connection: On its way to this famous military debacle, part of Braddock’s force marched right through Loudoun County, using roads that are still more or less in use today. -

Nomination Form

VLR Listed: 12/4/1996 NRHP Listed: 4/28/1997 NFS Form 10-900 ! MAR * * I99T 0MB( No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) .^^oTT^Q CES United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Skyline Drive Historic District other name/site number: N/A 2. Location street & number: Shenandoah National Park (SHEN) not for publication: __ city/town: Luray vicinity: x state: VA county: Albemarle code: VA003 zip code: 22835 Augusta VA015 Greene VA079 Madison VA113 Page VA139 Rappahannock VA157 Rockingham VA165 Warren VA187 3. Classification Ownership of Property: public-Federal Category of Property: district Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 9 8 buildings 8 3 sites 136 67 structures 22 1 objects 175 79 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: none Name of related multiple property listing: Historic Park Landscapes in National and State Parks 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x _ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x _ meets __^ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant x nationally __ statewide __ locally. ( __ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) _____________ Signature of certifying of ficial Date _____ ly/,a,-K OAJ.