The Chicago Academy of Sciences: the Development Method of Educational Work in Natural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian–American Telegraph from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from Western Union Telegraph Expedition)

Russian–American telegraph From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Western Union Telegraph Expedition) The Russian American telegraph , also known as the Western Union Telegraph Expedition and the Collins Overland telegraph , was a $3,000,000 undertaking by the Western Union Telegraph Company in 1865-1867, to lay an electric telegraph line from San Francisco, California to Moscow, Russia. The route was intended to travel from California via Oregon, Washington Territory, the Colony of British Columbia and Russian Alaska, under the Bering Sea and across Siberia to Moscow, where lines would communicate with the rest of Europe. It was proposed as an alternate to long, deep underwater cables in the Atlantic. Abandoned in 1867, the Russian American Telegraph was considered an economic failure, but history now deems it a "successful failure" because of the many benefits the exploration brought to the regions that were traversed. Contents ■ 1 Perry Collins and Cyrus West Field ■ 2 Preparations ■ 3 Route through Russian Alaska ■ 4 Route through British Columbia ■ 5 Legacy ■ 6 Places named for the expedition members ■ 7 Books and memoirs written about the expedition ■ 8 Further reading ■ 9 External links ■ 10 Notes Perry Collins and Cyrus West Field By 1861 the Western Union Telegraph Company had linked the eastern United States by electric telegraph all the way to San Francisco. The challenge then remained to connect North America with the rest of the world. [1] Working to meet that challenge was Cyrus West Field's Atlantic Telegraph Company, who in 1858 had laid the first undersea cable across the Atlantic Ocean. However, the cable had broken three weeks afterwards and additional attempts had thus far been unsuccessful. -

Taiga Plains

ECOLOGICAL REGIONS OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES Taiga Plains Ecosystem Classification Group Department of Environment and Natural Resources Government of the Northwest Territories Revised 2009 ECOLOGICAL REGIONS OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES TAIGA PLAINS This report may be cited as: Ecosystem Classification Group. 2007 (rev. 2009). Ecological Regions of the Northwest Territories – Taiga Plains. Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, NT, Canada. viii + 173 pp. + folded insert map. ISBN 0-7708-0161-7 Web Site: http://www.enr.gov.nt.ca/index.html For more information contact: Department of Environment and Natural Resources P.O. Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Phone: (867) 920-8064 Fax: (867) 873-0293 About the cover: The small photographs in the inset boxes are enlarged with captions on pages 22 (Taiga Plains High Subarctic (HS) Ecoregion), 52 (Taiga Plains Low Subarctic (LS) Ecoregion), 82 (Taiga Plains High Boreal (HB) Ecoregion), and 96 (Taiga Plains Mid-Boreal (MB) Ecoregion). Aerial photographs: Dave Downing (Timberline Natural Resource Group). Ground photographs and photograph of cloudberry: Bob Decker (Government of the Northwest Territories). Other plant photographs: Christian Bucher. Members of the Ecosystem Classification Group Dave Downing Ecologist, Timberline Natural Resource Group, Edmonton, Alberta. Bob Decker Forest Ecologist, Forest Management Division, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Hay River, Northwest Territories. Bas Oosenbrug Habitat Conservation Biologist, Wildlife Division, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. Charles Tarnocai Research Scientist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. Tom Chowns Environmental Consultant, Powassan, Ontario. Chris Hampel Geographic Information System Specialist/Resource Analyst, Timberline Natural Resource Group, Edmonton, Alberta. -

P1616 Text-Only PDF File

A Geologic Guide to Wrangell–Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska A Tectonic Collage of Northbound Terranes By Gary R. Winkler1 With contributions by Edward M. MacKevett, Jr.,2 George Plafker,3 Donald H. Richter,4 Danny S. Rosenkrans,5 and Henry R. Schmoll1 Introduction region—his explorations of Malaspina Glacier and Mt. St. Elias—characterized the vast mountains and glaciers whose realms he invaded with a sense of astonishment. His descrip Wrangell–Saint Elias National Park and Preserve (fig. tions are filled with superlatives. In the ensuing 100+ years, 6), the largest unit in the U.S. National Park System, earth scientists have learned much more about the geologic encompasses nearly 13.2 million acres of geological won evolution of the parklands, but the possibility of astonishment derments. Furthermore, its geologic makeup is shared with still is with us as we unravel the results of continuing tectonic contiguous Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, Kluane processes along the south-central Alaska continental margin. National Park and Game Sanctuary in the Yukon Territory, the Russell’s superlatives are justified: Wrangell–Saint Elias Alsek-Tatshenshini Provincial Park in British Columbia, the is, indeed, an awesome collage of geologic terranes. Most Cordova district of Chugach National Forest and the Yakutat wonderful has been the continuing discovery that the disparate district of Tongass National Forest, and Glacier Bay National terranes are, like us, invaders of a sort with unique trajectories Park and Preserve at the north end of Alaska’s panhan and timelines marking their northward journeys to arrive in dle—shared landscapes of awesome dimensions and classic today’s parklands. -

Hydrologic and Mass-Movement Hazards Near Mccarthy Wrangell-St

Hydrologic and Mass-Movement Hazards near McCarthy Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska By Stanley H. Jones and Roy L Glass U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 93-4078 Prepared in cooperation with the NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Anchorage, Alaska 1993 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ROBERT M. HIRSCH, Acting Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report may be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center 4230 University Drive, Suite 201 Open-File Reports Section Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4664 Box 25286, MS 517 Denver Federal Center Denver, Colorado 80225 CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................ 1 Introduction.............................................................. 1 Purpose and scope..................................................... 2 Acknowledgments..................................................... 2 Hydrology and climate...................................................... 3 Geology and geologic hazards................................................ 5 Bedrock............................................................. 5 Unconsolidated materials ............................................... 7 Alluvial and glacial deposits......................................... 7 Moraines........................................................ 7 Landslides....................................................... 7 Talus.......................................................... -

Yearbook02chic.Pdf

41 *( ^^Wk. _ f. CHICAGO LITERARY CLUB 1695-56 CHICAGO LITERARY CLUB YEAR-BOOK FOR 1895-96 Officer* for 1895-96 President. JOHN HENRY BARROWS. Vice-Presidents. FRANK H. SCOTT, HENRY S. BOUTELL, JAMES A. HUNT. Corresponding Secretary. DANIEL GOODWIN. Recording Secretary and Treasurer. FREDERICK W. GOOKIN. The above officers constitute the Board of Directors. Committees On Officers and Members. FRANK H. SCOTT, Chairman. ALLEN B. POND, ARTHUR D. WHEELER, THOMAS D. MARSTON, GEORGE L. PADDOCK. On Arrangements and Exercises. HENRY S. BOUTELL,C/tairman. EMILIUS C. DUDLEY, CHARLES G. FULLER, EDWARD O. BROWN, SIGMUND ZEISLER. On Rooms and Finance. JAMES A. HUNT, Chairman. WILLIAM R. STIRLING, JOHN H. HAMLINE, GEORGE H. HOLT, JAMES J. WAIT. On Publications. LEWIS H. BOUTELL, Chairman. FRANKLIN H. HEAD, CLARENCE A. BURLEY. Literarp Club Founded March 13, 1874 Incorporated July 10, 1886 ROBERT COLLYER, 1874-75 CHARLES B. LAWRENCE, 1875-76 HOSMER A. JOHNSON, 1876-77 DANIEL L. SHOREY, 1877-78 EDWARD G. MASON, . 1878-79 WILLIAM F. POOLE, 1879-80 BROOKE HERFORD, i 880-8 i EDWIN C. LARNED, 1881-82 GEORGE ROWLAND, . 1882-83 HENRY A. HUNTINGTON, 1883-84 CHARLES GILMAN SMITH, 1884-85 JAMES S. NORTON, 1885-86 ALEXANDER C. McCLURG, 1886-87 GEORGE C. NOYES, 1887-88 JAMES L. HIGH, . 1888-89 JAMES NEVINS HYDE, 1889-90 FRANKLIN H. HEAD, . 1890-91 CLINTON LOCKE, . 1891-92 LEWIS H. BOUTELL, . 1892-93 HORATIO L. WAIT, 1893-94 WILLIAM ELIOT FURNESS, 1894-95 JOHN HENRY BARROWS, 1895-96 Besfoent George E. Adams, Eliphalet W. Blatchford, Joseph Adams, Louis J. Block, Owen F. -

Nbsi Progress Report 2020

NBSI PROGRESS REPORT 2020 Atomic Force Micrograph of the Neuronal Porosome Complex Expansion Microscopy on Human Skeletal Muscle Cells Porosome: The secretory portal involved in neurotransmission A new modality in nanoscale imaging using an ordinary light microscope NanoBioScience Institute (NBSI) http://www2.med.wayne.edu/physiology/nanobioscience/nanobioscience.htm School of Medicine Wayne State University Progress Report Prof. Bhanu P. Jena Director, NBSI George E. Palade University Professor & Distinguished Professor March 5, 2020 NBSI was established in 2000 at the School of Medicine immediately after my arrival from Yale University School of Medicine and is the first and only existing ‘NanoBioScience Institute’ on our campus in this cutting-edge technology. The primary objective of the institute was to establish a strong interdisciplinary program in the Nano Sciences & Nano Medicine at the Medical School and the University. In summary, with no seed funding from the University, NBSI continues to contribute to the academic and research progress in the field, and to bring recognition to the School of Medicine and to Wayne State University. Some of the past and present contributions of NBSI are highlighted below: NBSI Highlights (Past & Present) 1. NBSI continues to bring together a large group of cross-campus interdisciplinary faculty and student groups to study Nano Science, Nano Medicine, & Nano Technology. 2. NBSI has facilitated joint grant applications and funding from the NSF, NIH, DOD, and other private sources. 3. NBSI Director (Jena) has developed a team-taught, campus-wide multidisciplinary NanoBioScience Course (PSL7215) in the Dept. of Physiology at the Medical School, which is in its 14th year of offering. -

Asc2006 Draft 1

Newsletter Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History February 2007www.mnh.si.edu/arctic Number 14 NOTES FROM THE DIRECTOR launched in January 2007, the Smithsonian will host a By Bill Fitzhugh research conference titled “Smithsonian at the Poles” on 3-4 May. Coordinated by Michael Lang and an SI-wide steering committee, with assistance from Under Secretary David Once every fifty years or so the world engages in a fit of Evans, the symposium will feature research papers on ‘arctic hysteria’ known as the International Polar Year. This historical legacies of Smithsonian IPY research and March we begin the fourth installment, IPY-4, which runs collecting from 1880 to the present as well as current until March of 2009. As we watch temperatures climbing, research in polar anthropology, biology, mineral sciences, Arctic sea ice and astrophysics. Small melting, and animals exhibits and public and peoples events are planned, and adjusting to the scholarly proceedings effects of global will be published in 2008. warming, what better The Smithsonian time could there be conference is only the for scientists to beginning. Federal investigate, and agencies have garnered laymen to learn resources to promote a about, one of the massive agenda of polar most dramatic earth- research and educational changes to come programs through 2008, along in the past and for the first time thousand or so national and international years? activities will have The Arctic significant participation Studies Center has from the social sciences taken IPY-4 by the and northern resident horns and communities. Igor anticipates a full Krupnik has taken a platter of research major role in securing a and educational center-stage position for programs. -

Community & Copper in a Wild Land

Community & Copper in a Wild Land McCarthy, Kennecott and Wrangell-St. Elias National Park & Preserve, Alaska Shawn Olson Ben Shaine The Wrangell Mountains Center McCarthy Copyright © 2005 by Shawn Olson and Ben Shaine. Illustrations copyright as credited. Photos not otherwise attributed are by the authors. Published by The Wrangell Mountains Center. Front cover photo by Nancy Simmerman, 1974. Back cover photos: McCarthy street in winter: NPS; child sledding, harvesting garden: Ben Shaine; dog team, fall color, cutting salmon, splitting firewood: Gaia Thurston-Shaine; mountain goat: WMC collection; Kennecott mill, flowers, McCarthy garden, snowmachine sled repair, Root Glacier hikers: Nancy Simmerman. The Wrangell Mountains Center McCarthy 20 P.O. Box MXY Glennallen, Alaska 99588 (907) 554-4464 / [email protected] www.wrangells.org The Wrangell Mountains Center is a private, non-profit institute dedicated to environmental education, research, and arts in Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias National Park & Preserve. Contents Introduction 1 Maps 3 Rocks and Mountains 7 Glaciers 9 Climate 17 Ecosystems 21 Plants: Trees 29 Flowers and berries 33 Mosses and Lichens 37 Animals: Birds 38 Mammals 42 Fish 47 Hunting and Fishing 48 Human History: The Ahtna 51 Copper Discovery & Development 53 Kennecott 60 McCarthy 64 After the Mines Closed 67 Designation of the Park 69 A New Economy and a Growing Community 71 The Park Service at Kennecott 75 Entryway to the Wild Wrangells 78 Hikes in the McCarthy-Kennecott Area 80 Appendix: Species Lists 81 Bibliography 84 Kennicott Glacier panorama. (Wrangell Mountains Center collection) Preface and acknowledgements As a general introduction to its natural and cultural history, this Artistic contributions are many. -

Vol. 24/ 4 (1943)

Reviews of Books The Development of Frederick Jac\son Turner as a Historical Thin\er. By FuLMER MOOD. (Reprinted from the Colonial Society of Massa chusetts, Transactions, 34:283-352.) So much has been written about that original mind, Frederick Jack son Turner, that one might think there was no room for further useful discussion of his development. But Dr. Mood's meticulous study is in deed a fresh and important contribution. Turner was born and raised in Portage, Wisconsin, where he saw at first hand the action of the melting pot and the growth of the democratic spirit. At the University of Wisconsin he worked on the college paper, delivered a prize oration upon "The Poet of the Future," and came un der the influence of William Francis Allen, professor of Latin and his tory. Allen believed in the topical approach to history, utilized many maps, set his students to using primary sources, and considered westward expansion and sectionalism the chief forces in American history. Turner stayed at Wisconsin, receiving a master's degree, writing a thesis on "The Influence of the Fur Trade in the Development of Wis consin," and teaching rhetoric, oratory, and American history. Dr. Mood shows clearly Turner's admiration for and close study of Scribner's His torical Atlas of the United States (1885) and the census reports of 1880. Turner spent a year in 1888-89 ^^ Johns Hopkins, where he was much influenced by Herbert Baxter Adams, Richard T. Ely, Woodrow Wilson, and others. Late in 1889 Professor Allen died, and Turner returned to Wisconsin to become head of the history department, a position which he held for twenty years. -

Le T I Liog Ph

A LE T I LIOG PH Dorothy M. Jones and John R. Wood Institute of Social, Economic and Government Research University of Alaska Standard Book Number: 0-88353-016-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 74-620054 · 44 Published by Institute of Social, Economic and Government Research University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 1975 Printed in the United States of America PREFACE This annotated bibliography on the Aleuts is one in a series of selected, annotated bibliographies on Alaska Native groups that is being published by the Institute of Social, Economic and Government Research. Forthcoming bibliographies in this series will collect and evaluate the existing literature on Eskimo and Southeastern Alaska Tlingit and Haida groups. ISEGR bibliographies are compiled and written by institute members who specialize in ethnographic and social research. They are designed both to support current work at the institute and to provide research tools for others interested in Alaska ethnography. Although not exhaustive, these bibliographies indicate the best references on Alaska Native groups and describe the general nature of the works. Victor Fischer, Director - Institute of Social, Economic and Government Research ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to extend our appreciation to all who helped us with this work. Particularly, we wish to thank Carol Berg, librarian at the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska, whose assistance was invaluable in obtaining through interlibrary loans many of the articles and books annotated in this bibliography. Peggy Raybeck and Ronald Crowe had general responsibility for editing and preparing the manuscript for publication, with the production assistance of Deanna Burrows. Cover design is by Mariana W. -

Seventh Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution to the Senate and House of Representatives, Showing

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 3-1-1853 Seventh annual report of the board of regents of the Smithsonian institution to the Senate and House of Representatives, showing the operations, expenditures, and condition of the institution during the year 1852, and the proceedings of the board of regents up to date. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Misc. Doc. No. 53, 32nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1853) This Senate Miscellaneous Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT OF TIIE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION TO THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, SHOWING THE OPERATIONS, EXPENDITURES, AND CONDITION OF THE INSTITUTION DURING THE YEAR 1852, AND THE .PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS UP TO DATE. WASHING TON: ROBERT .ARMSTRONG, PRINTER. 1853. 82d CONGRESS, [SENATE.] M1scELLANEous, 2d Session. No. 53. LETTER FROM THE SECRETARY OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, COMMUNIOATING The Annual Report of the Board of R egents. MARCH 1, 1853.-0rderei to lie on the table and be printed. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, A ugust 20, 1852. -

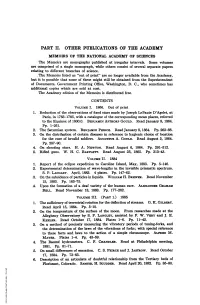

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2.