Ovid's Heroines and Feminine Discourse: Metamorphoses 7 and 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incest, Cannibalism, Filicide: Elements of the Thyestes Myth in Ovid’S Stories of Tereus and Myrrha

INCEST, CANNIBALISM, FILICIDE: ELEMENTS OF THE THYESTES MYTH IN OVID’S STORIES OF TEREUS AND MYRRHA Hannah Sorscher A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial ful- fillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Sharon L. James James J. O’Hara Emily Baragwanath © 2017 Hannah Sorscher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Hannah Sorscher: Incest, Cannibalism, Filicide: Elements of the Thyestes Myth in Ovid’s Stories of Tereus and Myrrha (Under the direction of Sharon L. James) This thesis analyzes key stories in Books 6–10 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses through a focus on the pair of stories that bookend the central section of the poem, the narratives of Tereus and Myrrha. These two stories exemplify the mythic types of the family-centered stories in Books 6– 10: Tereus’ is a tale of filicide (specifically, filial cannibalism), while Myrrha’s features incest. Ovid links these stories through themes and plot elements that are shared with the tragedy of Thyestes, a paradigmatic tragic myth encompassing both filial cannibalism and incest, otherwise untold in the Metamorphoses. Through allusions to Thyestes’ myth, Ovid binds together the se- quence of human dramas in the poem, beginning and ending with the Tereus and Myrrha stories. Furthermore, the poet reinforces and signals the connections between the stories through textual echoes, lexical formulations, and shared narrative elements. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Thyestes…………………………………………………………………………………………...2 Lexical Connections……………………………………………………………………………...13 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………….....34 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………...…3 iv Introduction In the central books of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, six episodes share a dark but very Ovidi- an theme: the destruction of human families. -

The Ovidian Soundscape: the Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses

The Ovidian Soundscape: The Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses Sarah Kathleen Kaczor Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Sarah Kathleen Kaczor All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Ovidian Soundscape: The Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses Sarah Kathleen Kaczor This dissertation aims to study the variety of sounds described in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and to identify an aesthetic of noise in the poem, a soundscape which contributes to the work’s thematic undertones. The two entities which shape an understanding of the poem’s conception of noise are Chaos, the conglomerate of mobile, conflicting elements with which the poem begins, and the personified Fama, whose domus is seen to contain a chaotic cosmos of words rather than elements. Within the loose frame provided by Chaos and Fama, the varied categories of noise in the Metamorphoses’ world, from nature sounds to speech, are seen to share qualities of changeability, mobility, and conflict, qualities which align them with the overall themes of flux and metamorphosis in the poem. I discuss three categories of Ovidian sound: in the first chapter, cosmological and elemental sound; in the second chapter, nature noises with an emphasis on the vocality of reeds and the role of echoes; and in the third chapter I treat human and divine speech and narrative, and the role of rumor. By the end of the poem, Ovid leaves us with a chaos of words as well as of forms, which bears important implications for his treatment of contemporary Augustanism as well as his belief in his own poetic fame. -

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy – Inferno

DIVINE COMEDY -INFERNO DANTE ALIGHIERI HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND NOTES PAUL GUSTAVE DORE´ ILLUSTRATIONS JOSEF NYGRIN PDF PREPARATION AND TYPESETTING ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND NOTES Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ILLUSTRATIONS Paul Gustave Dor´e Released under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial Licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ You are free: to share – to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work; to remix – to make derivative works. Under the following conditions: attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work); noncommercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. English translation and notes by H. W. Longfellow obtained from http://dante.ilt.columbia.edu/new/comedy/. Scans of illustrations by P. G. Dor´e obtained from http://www.danshort.com/dc/, scanned by Dan Short, used with permission. MIKTEXLATEX typesetting by Josef Nygrin, in Jan & Feb 2008. http://www.paskvil.com/ Some rights reserved c 2008 Josef Nygrin Contents Canto 1 1 Canto 2 9 Canto 3 16 Canto 4 23 Canto 5 30 Canto 6 38 Canto 7 44 Canto 8 51 Canto 9 58 Canto 10 65 Canto 11 71 Canto 12 77 Canto 13 85 Canto 14 93 Canto 15 99 Canto 16 104 Canto 17 110 Canto 18 116 Canto 19 124 Canto 20 131 Canto 21 136 Canto 22 143 Canto 23 150 Canto 24 158 Canto 25 164 Canto 26 171 Canto 27 177 Canto 28 183 Canto 29 192 Canto 30 200 Canto 31 207 Canto 32 215 Canto 33 222 Canto 34 231 Dante Alighieri 239 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow 245 Paul Gustave Dor´e 251 Some rights reserved c 2008 Josef Nygrin http://www.paskvil.com/ Inferno Figure 1: Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself within a forest dark.. -

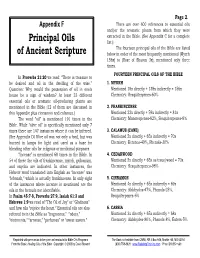

Principal Oils of Ancient Scripture

Page 2. Appendix F There are over 600 references to essential oils and/or the aromatic plants from which they were extracted in the Bible. (See Appendix C for a complete Principal Oils list.) The fourteen principal oils of the Bible are listed of Ancient Scripture below in order of the most frequently mentioned (Myrrh 156x) to (Rose of Sharon 3x), mentioned only three times. FOURTEEN PRINCIPAL OILS OF THE BIBLE In Proverbs 21:20 we read: “There is treasure to be desired and oil in the dwelling of the wise.” 1. MYRRH Question: Why would the possession of oil in one’s Mentioned 18x directly + 138x indirectly = 156x house be a sign of wisdom? At least 33 different Chemistry: Sesquiterpenes-60% essential oils or aromatic oil-producing plants are mentioned in the Bible (12 of them are discussed in 2. FRANKINCENSE this Appendix plus cinnamon and calamus.) Mentioned 22x directly + 59x indirectly = 81x The word “oil” is mentioned 191 times in the Chemistry: Monoterpenes-82%, Sesquiterpenes-8% Bible. While “olive oil” is specifically mentioned only 7 times there are 147 instances where it can be inferred. 3. CALAMUS (CANE) (See Appendix D) Olive oil was not only a food, but was Mentioned 5x directly + 65x indirectly = 70x burned in lamps for light and used as a base for Chemistry: Ketones-40%, Phenols-30% blending other oils for religious or medicinal purposes. “Incense” is mentioned 68 times in the Bible. In 4. CEDARWOOD 54 of these the oils of frankincense, myrrh, galbanum, Mentioned 5x directly + 65x as trees/wood = 70x and onycha are indicated. -

Failed Chastity and Ovid: Myrrha in the Latin Commentary Tradition from Antiquity to the Renaissance1

FAILED CHASTITY AND OVID: MYRRHA IN THE LATIN COMMENTARY TRADITION FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE RENAISSANCE1 Frank T. Coulson The preponderant infl uence of the poetry of Ovid on the artistic and cultural life of Europe from the Carolingian age to the end of the Renaissance has long been recognized, and numerous studies have documented the manner in which the tone, themes, style and ethos of both the amatory poems and Ovid’s epic poem, the Metamorphoses, informed such vernacular poets as Dante in Italian, Chaucer and Shakespeare in English, and the poets of the Pléiade in renaissance France. Here, it is not my purpose to investigate such monumental works of literature as the Commedia, but rather to trace a slenderer, yet in my view no less important thread in the complex tapestry of Ovidian infl uence in the Middle Ages and Renaissance—namely, the Latin school tradition on Ovid and, in particular, the commentaries that were written on the Metamorphoses from 1100 to 1600. These texts, as Alastair Minnis has recently shown in his magisterial study Medieval Literary Theory and Criticism c. 1100–c. 1375: The Commentary Tradition,2 are important witnesses to reading practices and literary interpretation during the medieval and humanistic periods. To date, however, these commentaries have not received the attention they deserve for several reasons. First, and perhaps foremost, the basic research necessary to uncover the manuscript witnesses of these texts and place them in their intellectual milieu is ongoing.3 Secondly, the majority of the texts, even 1 I am grateful to Marjorie Curry Woods for comments on an earlier draft of this article. -

The Lost Genre of Medieval Spanish Literature

THE LOST GENRE OF MEDIEVAL SPANISH LITERATURE Hispanists have frequent occasion to refer to the loss of much medieval literatura, and to recognize that the extant texts are not necessarily typical. There is no Hispanic equivalent of R. M. Wilson's The Lost Literatura of Medieval England1, but a similar, though less extensive, work could undoubtedly be compiled for Spanish, and Ramón Menéndez Pidal showed us how evidence for the contení, and sometimes the actual words, of lost epics could be discovered by cióse attention to chronicles and ballads. The study of literature which no longer survives has obvious dangers, and the concentration of Hispanists on lost epic and lost drama has oc- casionally gone further than the evidence justifies, leading to detailed accounts of poems or traditions, which, in all probability, never existed: for example, the supposed epic on King Rodrigo and the fall of Spain to the Moors, and the allegedly flourishing tradition of Castilian drama between the Auto de los reyes magos and Gómez Manrique. Nevertheless, many lost works can be clearly identified and set within the pattern of literary history. The study of lost literature can produce important modifications in that pattern, but changes of equal importance may result from a reassessment of extant works. There is a growing realization that medieval literature has been very unevenly studied, and the contrast between widespread interest in a few works and almost universal neglect of many others is especially acute in Spanish2. I propose to deal here with a particularly striking example of that neglect, which has been carried to the point where the existence of an important genre is overlooked. -

Spaces in Between in the Myth of Myrrha: a Metamorphosis Into Tree

Spaces In Between in the Myth of Myrrha: A Metamorphosis into Tree THIS IS NOT THE FINAL VERSION OF THE PAPER Ottilia VERES Partium Christian University (Oradea, Romania) Department of Literatures and Languages [email protected] Abstract Within the larger context of metamorphoses into plants in Greek myths, the paper aims to analyze the myth of Myrrha and her metamorphosis into a tree, focusing on the triggering cause of the transformation as well as the response given to the newly-acquired form of life. Myrrha’s transformation into a myrrh tree takes place as a consequence/punishment for her transgressive incestuous act of love with her father Cyniras. Her metamorphosis occurs as a consequence of sinful passion—passion in extremis—and she sacrifices her body (and human life/existence) in her escape. I’ll be looking at Ovid’s version of the myth as well as Ted Hughes’s adaptation of the story from his Tales from Ovid. My discussion of the transformation into tree starts out from the consideration that metamorphosis is the par excellence place and space of in-betweenness implying an inherent hybridity and blurred, converging subjectivities, a state of being that allows passages, overlaps, crossings and simultaneities. I am interested in what ways Myrrha’s incestuous desire for her father as well as her metamorphosis into a tree can be “rooted” back to her great grandfather Pygmalion’s transgression. Keywords: myth, metamorphosis, Myrrha, myrrh tree “Give me some third way [. .]. Remove me From life and from death Into some nerveless limbo.” (Hughes 1997, 127) 1 In Ovid, Myrrha’s story comes right after that of Pygmalion, as a consequence of—and as a “punishment” for—Pygmalion’s sinful deed, his “incestuous” love with “his kind”—Galatea, the woman he “fathered” (created). -

Caesarean Section in Ancient Greek Mythology

Esej Acta med-hist Adriat 2015; 13(1);209-216 Essay UDK: 61(091):618.5-089.888.61(38 CAESAREAN SECTION IN ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY CARSKI REZ U GRČKOJ MITOLOGIJI Samuel Lurie* Summary The narrative of caesarean birth appears on several occasions in Greek mythology: in the birth of Dionysus is the God of the grape harvest and winemaking and wine; in the birth of Asclepius the God of medicine and healing; and in the birth of Adonis the God of beauty and desire. It is possible, however not obligatory, that it was not solely a fantasy but also reflected a contemporary medical practice. Key words: Caesarean Section, Greek Mythology, Ancient World. Myth is usually defined as a traditional sacred narrative transmitted from one generation to another in which a social or universal lack is satisfied. Myths are generally classified as follows: ‒ cosmogenic myths; ‒ myths about divine beings; ‒ myths about creation of men; ‒ myths about subsequent modification of the world; ‒ myth about the celestial bodies and the life of nature; and ‒ myth about heroes [1]. * Prof. Samuel Lurie, MD. Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Edith Wolfson Medical Center. Holon and Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel. e-mail: [email protected] 209 For the ancient Greeks, myth (μύθος) meant “fable”, “tale”, “talk” or “speech” [1]. Thus, ancient Greek mythology is a collection of stories con- cerning their gods and heroes, the family life of the gods, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their ritual practices [2]. Although they distinguished between “myth” and “history”, for the ancient Greeks, mythology, particularly heroic, was their ancient history [2]. -

Resolving Frazer and Segal's Interpretations of the Adonis Myth

THE ADONIS COMPLEX: RESOLVING FRAZER AND SEGAL’S INTERPRETATIONS OF THE ADONIS MYTH By Carman Romano, Haverford College Persephone: The Harvard Undergraduate Classics Journal Vol. 1, No. 1, Winter 2016 p. 46-59. http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/persephone/adonis-complex- resolving-frazers-and-segals-interpretations-adonis-myth-0 The Adonis Complex: Resolving Frazer's and Segal's Interpretations of the Adonis Myth Carman Romano Haverford College Overview In their analyses of the Adonis myth, Sir James George Frazer and Robert A. Segal cite numerous ancient variants of Adonis’ myth and evidence of the Adonia, a ritual that commemorated Adonis’ death, as evidence for their respective readings. Each emphasizes the evidence which best agrees with his own interpretive method; evidence which is itself informed by presuppositions about myth and ritual. Frazer assumes that myth should be rationalized and universalized, and believes the ritual dependent on it. He equates Adonis to Tammuz, Attis, and Osiris, other deities whose death and rebirth, he argues, represent the decay and renewal of vegetable life. Because of these presuppostions, Frazer downplays those variants of Adonis’ myth in which the deity dies a “final” death and emphasizes ritual evidence, arguing that the Adonia reenacts Adonis’ death annually.1 Segal, by contrast, presupposes the relevance of myth to psychology and ritual's ability not to reenact, but to express those same ideas present in myth. He thus employs a Jungian interpretive method, believing Adonis a Greek manifestation of the puer archetype whose myth must end in “premature death” and whose negative exemplar “dramatizes the prerequisites for membership in the polis.”2 Segal’s interpretive method requires that Adonis die a “final” death, and he prefers those variants of the myth which suppose Adonis’ death and insists that the Adonia, rather than reenact myth, expresses its ideas of sterility and immaturity. -

Myrrh Essential Oil, Commiphora Myrrha Norfolk Essential Oils LTD

Amrita Aromatherapy, Inc. 1900 W. Stone Ave Unit C Fairfield, Iowa 52556 Phn: 641.472.9136 Fax: 641.472.8672 Contact: Lise Marcell [email protected] March 6, 2008 Submission of petltlon for National List Amendment: Non-organic agricultural substances allowed in or on processed products labeled as "organic,", Sec. 205.606. 1. Substance's chemical or material common name. Myrrh essential oil, commiphora myrrha 2. Manufacturer/producer's name, address, phone, contact. Norfolk Essential oils LTD. pates Farm, Risbech Road Tipsend, welney, PE14 9SQ united Kingdom. phn: 011 44 1354638065 3. Intended or current use of substance, such as processing aid, nonagricultural ingredient, disinfectant. If the substance is an agricultural ingredient, the petition must provide a list of the types of product(s) (eg cereals, salad dressings) for which the substance will be used and a description of the substance's function in the product(s) (e.g., ingredient, flavoring agent, emulsifier, processing aid). TO be used as a scent in a perfume 4. List of the handling activities for which the substance will be used. If used for handling (including processing) the substance's mode of action must be described. TO be mixed with jojoba oil, vitamin E and other essential oils to manufacture perfumes. 5. Source of the substance and a detailed description of its manufacturing or processing procedures from the basic component/s to the final product. Myrrh grows as a wild shrub in north east Africa and south west Asia. The trunk exudes a natural oleoresin, which is collected and steam distilled to produce the essential oil. -

Allusions in Dante's Infemo

The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research Volume 5 Article 9 2002 Allusions in Dante's Infemo Sarah Landas St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Landas, Sarah. "Allusions in Dante's Infemo." The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research 5 (2002): 91-112. Web. [date of access]. <https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol5/iss1/9>. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol5/iss1/9 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Allusions in Dante's Infemo Abstract In lieu of an abstract, below is the essay's first paragraph. "Vexilla regis produent inferni; the banners of the king go forth, the king of Hell" (Vergani 74). In a place called Dis, the demon Satan resides. He has three hideous heads and spends his time crying from six eyes, while the tears mingle with the blood of three tortured sinners. These sinners, Brutus, Cassius, and Judas Iscariot, are ground to bits by Lucifer's gnashing teeth, while Judas alone receives the benefit of also having his back stripped of its skin as retribution for him being the greatest sinner to be found in all of Hell. This illustration is presented in a graphic and figurative manner, thus making it a prime example of the type of allusion that Dante Alighieri uses throughout the Inferno the first section of his literary classic, The Divine Comedy. -

Metamorphoses

A NOISE WITHIN SPRING 2021 STUDY GUIDE Metamorphoses Based on the Myths of Ovid Written and originally directed by Mary Zimmerman Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott February 7–May 7, 2021 Edu STUDY GUIDES FROM A NOISE WITHIN A rich resource for teachers of English, reading, arts, and drama education. Dear Reader, We’re delighted you’re interested in our study guides, designed to provide a full range of information on our plays to teachers of all grade levels. A Noise Within’s study guides include: • General information about the play (characters, synopsis, timeline, and more) • Playwright biography and literary analysis • Historical content of the play • Scholarly articles • Production information (costumes, lights, direction, etc.) • Suggested classroom activities • Related resources (videos, books, etc.) • Discussion themes • Background on verse and prose (for Shakespeare’s plays) Our study guides allow you to review and share information with students to enhance both lesson plans and pupils’ theatrical experience and appreciation. They are designed to let you extrapolate articles and other information that best align with your own curricula and pedagogic goals. Pictured: Carolyn Ratteray, Evan Lewis Smith, and Veralyn Jones, Gem of the Ocean More information? It would be our pleasure. We’re 2019. PHOTO BY CRAIG SCHWARTZ. here to make your students’ learning experience as rewarding and memorable as it can be! All the best, Alicia Green DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION Special thanks to our Dinner On Stage donors TABLE OF CONTENTS who kept the