Perceptions of Challenges to Subsistence Agriculture, and Crop Foraging by Wildlife and Chimpanzees Pan Troglodytes Verus in Unprotected Areas in Sierra Leone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kailahun District Constituencies And

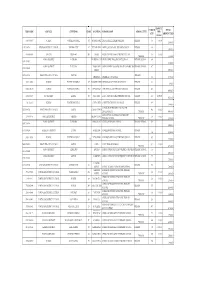

NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation Process Process Delimitation Boundaries Constituency Electoral on Report NEC: 4.1.1 KAILAHUN DISTRICT CONSTITUENCIES AND POPULATION Eastern Region Constituency Maps 1103 a 43,427 m i a g g n K n e i o s T s T i i i s Penguia s K is is Yawei K K Luawa 1101 e 49,499 r 1104 1108 g n 33,457 54,363 o B Kpeje je e Upper West p K Bambara 1102 44,439 1107 Chiefdom Boundary 37,484 Constituency Code Njaluahun Mandu – 1101 Constituency 1 August 2006 August Dea 1102 Constituency 2 Jawie 1103 Constituency 3 1106 Malema 1104 Constituency 4 42,639 1105 Constituency 5 1105 1106 Constituency 6 52,882 1107 Constituency 7 1108 Constituency 8 42,639 Constituency Population PREPARED BY STATISTICS SIERRA LEONE KENEMA DISTRICT CONSTITUENCIES AND POPULATION Gorama Mende 1207 49,953 Wandor 1206 48,429 n u h Simbaru o g Lower le 1208 Dodo Bambara a M 54,312 1205 42,184 Kandu Leppiama 1204 51,486 1202 1201 42,262 Nongowa 43,308 # Small Bo # Kenema # 1203 1209 Town 42,832 44,045 Dama 1210 Niawa 36341 Gaura Langrama Koya 1211 Nomo 42,796 Chiefdom Boundary Constituency Code Tunkia 1201 Constituency 1 1202 Constituency 2 1203 Constituency 3 1204 Constituency 4 1205 Constituency 5 1206 Constituency 6 1207 Constituency 7 1208 Constituency 8 1209 Constituency 9 1210 Constituency 10 1211 Constituency 11 42,796 Constituency Population PREPARED BY STATISTICS SIERRA LEONE NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation Process – August 2006 NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation -

Summary of Recovery Requirements (Us$)

National Recovery Strategy Sierra Leone 2002 - 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 4. RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY 48 INFORMATION SHEET 7 MAPS 8 Agriculture and Food-Security 49 Mining 53 INTRODUCTION 9 Infrastructure 54 Monitoring and Coordination 10 Micro-Finance 57 I. RECOVERY POLICY III. DISTRICT INFORMATION 1. COMPONENTS OF RECOVERY 12 EASTERN REGION 60 Government 12 1. Kailahun 60 Civil Society 12 2. Kenema 63 Economy & Infrastructure 13 3. Kono 66 2. CROSS CUTTING ISSUES 14 NORTHERN REGION 69 HIV/AIDS and Preventive Health 14 4. Bombali 69 Youth 14 5. Kambia 72 Gender 15 6. Koinadugu 75 Environment 16 7. Port Loko 78 8. Tonkolili 81 II. PRIORITY AREAS OF SOUTHERN REGION 84 INTERVENTION 9. Bo 84 10. Bonthe 87 11. Moyamba 90 1. CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY 18 12. Pujehun 93 District Administration 18 District/Local Councils 19 WESTERN AREA 96 Sierra Leone Police 20 Courts 21 Prisons 22 IV. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS Native Administration 23 2. REBUILDING COMMUNITIES 25 SUMMARY OF RECOVERY REQUIREMENTS Resettlement of IDPs & Refugees 26 CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY Reintegration of Ex-Combatants 38 REBUILDING COMMUNITIES Health 31 Water and Sanitation 34 PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS Education 36 RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY Child Protection & Social Services 40 Shelter 43 V. ANNEXES 3. PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS 46 GLOSSARY NATIONAL RECOVERY STRATEGY - 3 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ▪ Deployment of remaining district officials, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including representatives of line ministries to all With Sierra Leone’s destructive eleven-year conflict districts (by March). formally declared over in January 2002, the country is ▪ Elections of District Councils completed and at last beginning the task of reconstruction, elected District Councils established (by June). -

Rapid Health Impact Assessment, Sierra Rutile Limited

Sierra Rutile Limited Sierra Rutile Project Area 1- Environmental, Social and Health Impact Assessment Specialist Rapid Health Impact Assessment For SRK Consulting Date Completed: 23rd February 2018 Version: Final Version Prepared by: SHAPE Consulting Limited Dr Mark Divall MB.ChB, DA, DTMH, DOHM, Cert TM, Cert HIA, Cert Env Med Dr Milka Owuor MB.ChB, MSc ETH Address all correspondence Email: +27 71 6720571 to Dr Mark Divall [email protected] This work is commissioned by Sierra Rutile Limited (SRL) and Iluka Resources on terms specifically limiting the liability of the authors. SHAPE Consulting Ltd conducted the work with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the contract with SRK Consulting and the client. Our conclusions are the results of the exercise of our professional judgement based in part upon materials and information provided by SRL and others. We disclaim any responsibility and liability to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the work. This work is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom the deliverables, or any part thereof, is made known. © SHAPE Consulting Limited, 2017. All rights reserved. This report is prepared solely for the benefit of and use by Sierra Rutile Limited. SHAPE Consulting Limited owns and retains all intellectual property rights in this report. This document is the copyright property of Sierra Rutile Limited and contains information that is confidential. Any request to copy or circulate any part of this document will require prior approval. Sierra Rutile Limited, Sierra Leone Rapid Health Impact Assessment February 2018 Executive Summary Introduction SHAPE Consulting Limited (SHAPE) was appointed by SRK Consulting (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd. -

THE REBEL WAR YEARS WERE CATALYTIC to DEVELOPMENT in the SOCIAL ADVANCEMENT of WOMEN in POST-WAR SIERRA LEONE” a Dissertation in Fulfilment for the Award Of

St. Clements University “THE REBEL WAR YEARS WERE CATALYTIC TO DEVELOPMENT IN THE SOCIAL ADVANCEMENT OF WOMEN IN POST-WAR SIERRA LEONE” A Dissertation In fulfilment For the Award of DDooccttoorr oo ff PPhhiilloossoopphhyy Submitted by: Christiana A.M. Thorpe B.A. Hons. Modern Languages Master of University Freetown – Sierra Leone May 2006 Dedication To the Dead: In Loving memory of My late Grandmother Christiana Bethia Moses My late Father – Joshua Boyzie Harold Thorpe My late Brother Julius Samuel Harold Thorpe, and My late aunty and godmother – Elizabeth Doherty. To the Living: My Mum: - Effumi Beatrice Thorpe. My Sisters: - Cashope, Onike and Omolora My Brothers: - Olushola, Prince and Bamidele My Best Friend and Guide: Samuel Maligi II 2 Acknowledgements I am grateful to so many people who have been helpful to me in accomplishing this ground breaking, innovative and what is for me a very fascinating study. I would like to acknowledge the moral support received from members of my household especially Margaret, Reginald, Durosimi, Yelie, Kadie and Papa. The entire membership and Institution of the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) Sierra Leone Chapter has been a reservoir of information for this study. I thank Marilyn, Gloria and Samuel for their support with the Secretariat and research assistance. To the hundreds of interviewees for their timely responses, trust and confidence, I will ever remain grateful. To daddy for the endless hours of brainstorming sessions and his inspirational support. Finally I would like to convey my gratitude to Dr. Le Cornu for his painstaking supervision in making this study a reality. -

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. -

THE YAWRI BAY OVERVIEW Kambia District the YAWRI BAY Is Located on the Coast of Sierra Leone, on the Atlantic Ocean

West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change Program THE YAWRI BAY OVERVIEW Kambia District THE YAWRI BAY is located on the coast of Sierra Leone, on the Atlantic Ocean. The Bay opens to the south-west of the country and is located about 25 km south of Freetown. LAND AREA Freetown Sierra Leone The total area of Yawri Bay is estimated at 29,505 ha. 29,505 ha PEOPLE • The Themene and Mende are the majority • 40.7% of the population (age 10 and above) ethnic groups. The region is also known to is illiterate. have several cosmopolitan settlements. • 88.3% of the Yawri Bay communities have • The local government operates through access to improved sources of drinking the Moyamba District council which has water such as public taps and well-secured legislative, financial, and administrative rivers or streams. powers. The district is further divided • Sanitation facilities include communal bush, into 14 chiefdoms controlled by tradition river beds, latrines, and buckets. Paramount Chiefs. • The Western area rural district (Waterloo) • The Western Area Rural District has a total is connected to the national grid and population of 444,270 people (221,351 receives hydro-powered electricity in the males and 22,1919 females). The Moyamba rainy season. Most other communities in District has 318,588 inhabitants (153,699 Yawri Bay depend on rechargeable batteries males and 164,889 females). or solar-powered devices for electricity. ECONOMY The employment rate The region is home to Agriculture is the main is 56% in the Moyamba some of the Sierra Leone’s economic driver in District and 73% in the primary fisheries and trade Moyamba, while trade Western rural area. -

Local Government and Paramount Chieftaincy in Sierra Leone: a Concise Introduction

Local Government and Paramount Chieftaincy in Sierra Leone: A Concise Introduction P. C. Gbawuru Mansaray III (alias Pagay) P. C. Alimamy Lahai Mansaray V Dembelia Sinkunia Chiefdom P. C. Madam Doris Lenga-Caulker P. C. Henry Fangawa of Gbabiyor II of Kagboro Chiefdom, Wandor Chiefdom, Falla Shenge (Moyamba District), (Kenema District), P. C. Theresa Vibbi III. of Kandu Leppiama, Gbadu Levuma (Kenema District) M. N. Conteh Revised Edition 2019 Local Government and Paramount Chieftaincy in Sierra Leone: A Concise Introduction A cross-section of Paramount Chiefs of Sierra Leone displaying their new staffs M. N. Conteh Revised Edition 2019 Table of Contents Page Contents i Acronyms ii Preface and acknowledgements iii About the Author v Chapter 1. 1 Local Government in Sierra Leone Chapter 2. 38 Paramount Chieftaincy in Sierra Leone: an introduction to its history and Electoral Process. Chapter 3. 80 Appendices Appendix 1: List of Chiefdoms and their Ruling Houses 82 Appendix 2: NEC Form PC 3 – statutory Declaration of Rights for 103 PC elections Appendix 3: List of symbols for PC elections (and Independent 105 candidates for Local Councils). Appendix 4: Joint Reporting Format for PC elections 107 Appendix 5 and 6: Single and multi-member wards for District 111 Councils. Appendix 7 Nomination Form for Local Council Candidate 114 References and Suggested books for further reading 1 16 i Acronyms APC – All Peoples’ Congress CC – Chiefdom Council / Chiefdom Committee DC – District Commissioner /District Council DEO – District Electoral Officer -

Moyamba District)

VILLAGE RESPONSES TO EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE IN RURAL CENTRAL SIERRA LEONE Paul Richards, Joseph Amara, Esther Mokuwa, AlFred Mokuwa, Roland Suluku NJALA UNIVERSITY Acknowledgements We thank ESRC grant # ES/J017620/1 and UKAid Ebola response funding to the Social Mobilization and Action Consortium for financial support January 12th 2015 1 2 Executive Summary 1. Ebola Virus Disease in Sierra Leone is spread by human-to-human contact. Most infection takes place through contact with body fluids of sick patients by those caring For them in the final "wet" phase of the disease or through handling the corpse in preparation for burial. 2. Programs are in place to block both inFection routes. Patients are encouraged to report early (in the first three days of initial symptoms) For palliative care in biosecure treatment Facilities, thus increasing chances of survival, e.g. through rehydration therapy, and reducing transmission rates by attenuating risks to Family carers during the last and most virulent phase oF the disease. Families who have sufFered an Ebola bereavement are required not to handle the corpse themselves, but to request the help oF a trained burial to carry out a safe burial. 3. Both early isolation and safe burial have suFFered From logistical problems. Initially, there was a shortage oF treatment places as the epidemic surged, and "saFe burial" teams were oFten slow to respond, due to overwork and lack of key facilities, such as vehicles. Teams have been expanded, and vehicles supplied, and as a result there is a prompt response to 95% oF calls For assistance. 4. But there are other obstacles to be overcome - that patients do not report early enough, and "safe burials" clash with local cultural norms for decent burial. -

2017 Constituency Boundary Delimitation Report, Vol. 2

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Republic of Sierra Leone Constituency Boundary Delimitation Report Volume 2 August, 2017 Foreword The National Electoral Commission (NEC) is submitting this report on the delimitation of constituency and ward boundaries in adherence to its constitutional mandate to delimit electoral constituency and ward boundaries, to be done “not less than five years and not more than seven years”; and complying with the timeline as stipulated in the NEC Electoral Calendar (2015-2019). The report is subject to Parliamentary approval, as enshrined in the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone (Act No 6 of 1991); which inter alia states delimitation of electoral boundaries to be done by NEC, while Section 38 (1) empowers the Commission to divide the country into constituencies for the purpose of electing Members of Parliament (MPs) using Single Member First- Past –the Post (FPTP) system. The Local Government Act of 2004, Part 1 –preliminary, assigns the task of drawing wards to NEC; while the Public Elections Act, 2012 (Section 14, sub-sections 1 &2) forms the legal basis for the allocation of council seats and delimitation of wards in Sierra Leone. The Commission appreciates the level of technical assistance, collaboration and cooperation it received from Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL), the Boundary Delimitation Technical Committee (BDTC), the Boundary Delimitation Monitoring Committee (BDMC), donor partners, line Ministries, Departments and Agencies and other key actors in the boundary delimitation exercise. The hiring of a Consultant, Dr Lisa Handley, an internationally renowned Boundary delimitation expert, added credence and credibility to the process as she provided professional advice which assisted in maintaining international standards and best practices. -

Pdf Projdoc.Pdf

Sierra Leone is one of the poorest countries in the world. For years, it has battled through wars and recently overcome the dangerous and deadly Ebola epidemic. Families have ALL PROGRAMS broken apart and are now homeless; COST/WHAT WE NEED orphanages are overflowing; and To provide a school feeding program for nearly 2,000 Sierra food and jobs are scarce. The country Leonean children living in extreme poverty—children who might otherwise not eat—for one year we need— is working to restore its economy— finding ways to heal. Yet countless 1,200 students in Banta $ 66,600.00 students in Kenema 19,236.00 challenges remain. 350 390 students in Freetown 16,380.00 Now more than ever the people of 30 students in Kossoh Town 1,260.00 Sierra Leone need your support, $103,476.00 particularly the children. Because the future of our world lies in the hands of HELP US SUPPORT SCHOOL FEEDING PROGRAMS children, nurturing and educating them SIERRA LEONE, WEST AFRICA should be the country’s top priority. DONATE TODAY brighterafrica.org Sarah Armstrong, Director [email protected] Sarah Armstrong founded BTA, a 501 (c) 3 organization in 2004 because of her limitless desire to help women and children in Africa. HELP US SUPPORT SCHOOL FEEDING PROGRAMS SIERRA LEONE, WEST AFRICA trim here for interior fold, adjust as necessary A Brighter Tomorrow for Africa Foundation (BTA) is, and has been for years, making a difference through the establishment of school feeding programs. There is ample evidence that school feeding programs make a truly positive difference in children’s lives as they provide— Nourishment through meals they would otherwise not get. -

Downloaded Cc-By-Nc from License.Brill.Com09/29/2021 02:25:30AM Via Free Access

chapter 4 Fragmentation and the Temne: From War Raids into Ethnic Civil Wars The Temne and Their Neighbours: A Long-Standing Scenario of Inter-ethnic Hostilities? The former British colony of Sierra Leone is today regarded as one of the classic cases of a society that is politically polarised by ethnic antagonism. By the 1950s, the decade before independence, ethnic fault lines had an impact on local political life and the inhabitants of the colony appeared to practise ethnic voting. Both the Sierra Leone People’s Party (slpp) government formed after 1957, led by Milton Margai, and the All People’s Congress (apc) government of Siaka Stevens coming to power in 1967/68, relied on ethnic support and cre- ated ethnic networks: the slpp appeared to be ‘southern’ and ‘eastern’, and Mende-dominated, the apc ‘northern’ and Temne-led.1 Between 1961 and the 1990s, such voting behaviour can be found in sociological and political science survey data.2 However, the period of brutal civil war in the 1990s weakened some of these community links, as local communities were more interested in their survival than in ethnic solidarities.3 We have seen that the 2007 legislative elections contradicted this apparent trend. Before the second half of the nineteenth century, the territory of present-day Sierra Leone was politically fragmented into a number of different small structures, which were often much smaller than the pre-colonial states of Senegambia (Map 4). The only regional exception was the ‘federation’ of Morea, which, however, was an unstable entity. The slave trade and the ‘legitimate commerce’ in palm 1 Cartwright, John R., Politics in Sierra Leone 1947–67 (Toronto – Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1970), 101–2, 128; Fisher, ‘Elections’, 621–3; Riddell, J.