Schubert Winterreise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2012 Calendar of Events

AUGUST 2012 CALENDAR OF EVENTS For complete up-to-date information on the campus-wide performance schedule, visit www.LincolnCenter.org. Calendar information LINCOLN CENTER THEATER LINCOLN CENTER LINCOLN CENTER is current as of War Horse OUT OF DOORS OUT OF DOORS Based on a novel by Brandt Brauer Frick Ensemble Phil Kline: dreamcitynine June 25, 2012 Michael Morpurgo (U.S. debut) performed by Talujon Adapted by Nick Stafford Damrosch Park 7:30 PM Sixty percussionists throughout August 1 Wednesday In association with Handspring the Plaza perform a live version of LINCOLN CENTER FILM SOCIETY OF Puppet Company Phil Kline’s GPS-based homage to Vivian Beaumont Theater 2 & 8 PM OUT OF DOORS John Cage’s Indeterminacy. LINCOLN CENTER Josie Robertson Plaza 6:30 PM To view the Film Society's On Sacred Ground: August schedule, visit LINCOLN CENTER PRESENTS Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring LINCOLN CENTER www.filmlinc.com MOSTLY MOZART FESTIVAL Arranged and Performed by OUT OF DOORS Mostly Mozart The Bad Plus LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL Damrosch Park 8:30 PM Chio-Tian Folk Drums and Festival Orchestra: Arts Group (U.S. debut) In Paris: Opening Night LINCOLN CENTER THEATER Hearst Plaza 7:30 PM Dmitry Krymov Laboratory Louis Langrée, conductor War Horse Dmitry Krymov, direction Nelson Freire, piano LINCOLN CENTER Based on a novel by and adaption Lawrence Brownlee, tenor OUT OF DOORS With Mikhail Baryshnikov, (Mostly Mozart debut) Michael Morpurgo Kimmo Pohjonen & Anna Sinyakina, Maxim All-Mozart program: Adapted by Nick Stafford Helsinki Nelson: Maminov, Maria Gulik, Overture to La clemenza di Tito In association with Handspring Accordion Wrestling Dmitry Volkov, Polina Butko, Piano Concerto No. -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, -

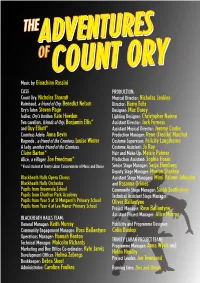

Adventures Adventures

THEADVENTURESADVENTURES COUNTCOUNT ORYORY Music by Gioachino Rossini CAST: PRODUCTION: Count Ory: Nicholas Sharratt Musical Director: Nicholas Jenkins Raimbaud, a friend of Ory: Benedict Nelson Director: Harry Fehr Ory’s Tutor: Steven Page Designer: Max Dorey Isolier, Ory’s brother: Kate Howden Lighting Designer: Christopher Nairne Two cavaliers, friends of Ory: Benjamin Ellis* Assistant Director: Jack Furness and Guy Elliott* Assistant Musical Director: Jeremy Cooke Countess Adele: Anna Devin Production Manager: Rene (Freddy) Marchal Ragonde , a friend of the Countess: Louise Winter Costume Supervisor: Felicity Langthorne A lady, another friend of the Countess: Costume Assistant: Jo Ray Claire Barton* Hair and Make-Up: Maisie Palmer Alice, a villager: Zoe Freedman* Production Assistant: Sophie Horan *Vocal student at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance Senior Stage Manager: Sasja Ekenberg Deputy Stage Manager: Marian Sharkey Blackheath Halls Opera Chorus Assistant Stage Managers: Mimi Palmer-Johnston Blackheath Halls Orchestra and Rosanna Grimes Pupils from Greenvale School Community Stage Manager: Sarah Southerton Pupils from Charlton Park Academy Technical Assistant Stage Manager: Pupils from Year 5 at St Margaret’s Primary School Oliver Ballantyne Pupils from Year 4 at Lee Manor Primary School Project Manager: Rose Ballantyne Assistant Project Manager: Alice Murray BLACKHEATH HALLS TEAM: General Manager: Keith Murray Publicity and Programme Designer: Community Engagement Manager: Rose Ballantyne Colin Dunlop Operations Manager: Hannah Benton TRINITY LABAN PROJECT TEAM: Technical Manager: Malcolm Richards Programme Manager: Anna Wyatt and Marketing and Box Office Co-ordinator:Kyle Jarvis Helen Hendry Development Officer:Helma Zebregs Project Leader: Joe Townsend Bookkeeper: Debra Skeet Administrator: Caroline Foulkes Running time: 2hrs and 30mins We have been staging community operas at Blackheath WELCOME Halls since July 2007. -

Sir Colin Davis Anthology Volume 1

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live Sir Colin Davis Anthology Volume 1 Sir Colin Davis conductor Colin Lee tenor London Symphony Chorus London Symphony Orchestra Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Symphonie fantastique, Op 14 (1830–32) Recorded live 27 & 28 September 2000, at the Barbican, London. 1 Rêveries – Passions (Daydreams – Passions) 15’51’’ Largo – Allegro agitato e appassionato assai – Religiosamente 2 Un bal (A ball) 6’36’’ Valse. Allegro non troppo 3 Scène aux champs (Scene in the fields) 17’16’’ Adagio 4 Marche au supplice (March to the Scaffold) 7’02’’ Allegretto non troppo 5 Songe d’une nuit de sabbat (Dream of the Witches’ Sabbath) 10’31’’ Larghetto – Allegro 6 Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Overture: Béatrice et Bénédict, Op 27 (1862) 8’14’’ Recorded live 6 & 8 June 2000, at the Barbican, London. 7 Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Overture: Les francs-juges, Op 3 (1826) 12’41’’ Recorded live 27 & 28 September 2006, at the Barbican, London. Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Te Deum, Op 22 (1849) Recorded live 22 & 23 February 2009, at the Barbican, London. 8 i. Te Deum (Hymne) 7’23’’ 9 ii. Tibi omnes (Hymne) 9’57’’ 10 iii. Dignare (Prière) 8’04’’ 11 iv. Christe, Rex gloriae (Hymne) 5’34’’ 12 v. Te ergo quaesumus (Prière) 7’15’’ 13 vi. Judex crederis (Hymne et prière) 10’20’’ 2 Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) – Symphony No 9 in E minor, Op 95, ‘From the New World’ (1893) Recorded live 29 & 30 September 1999, at the Barbican, London. 14 i. Adagio – Allegro molto 12’08’’ 15 ii. Largo 12’55’’ 16 iii. -

2016/17 Season Preview and Appeal

2016/17 SEASON PREVIEW AND APPEAL The Wigmore Hall Trust would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals and organisations for their generous support throughout the THANK YOU 2015/16 Season. HONORARY PATRONS David and Frances Waters* Kate Dugdale A bequest from the late John Lunn Aubrey Adams David Evan Williams In memory of Robert Easton David Lyons* André and Rosalie Hoffmann Douglas and Janette Eden Sir Jack Lyons Charitable Trust Simon Majaro MBE and Pamela Majaro MBE Sir Ralph Kohn FRS and Lady Kohn CORPORATE SUPPORTERS Mr Martin R Edwards Mr and Mrs Paul Morgan Capital Group The Eldering/Goecke Family Mayfield Valley Arts Trust Annette Ellis* Michael and Lynne McGowan* (corporate matched giving) L SEASON PATRONS Clifford Chance LLP The Elton Family George Meyer Dr C A Endersby and Prof D Cowan Alison and Antony Milford L Aubrey Adams* Complete Coffee Ltd L American Friends of Wigmore Hall Duncan Lawrie Private Banking The Ernest Cook Trust Milton Damerel Trust Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne‡ Martin Randall Travel Ltd Caroline Erskine The Monument Trust Karl Otto Bonnier* Rosenblatt Solicitors Felicity Fairbairn L Amyas and Louise Morse* Henry and Suzanne Davis Rothschild Mrs Susan Feakin Mr and Mrs M J Munz-Jones Peter and Sonia Field L A C and F A Myer Dunard Fund† L The Hargreaves and Ball Trust BACK OF HOUSE Deborah Finkler and Allan Murray-Jones Valerie O’Connor Pauline and Ian Howat REFURBISHMENT SUMMER 2015 Neil and Deborah Franks* The Nicholas Boas Charitable Trust The Monument Trust Arts Council England John and Amy Ford P Parkinson Valerie O’Connor The Foyle Foundation S E Franklin Charitable Trust No. -

“Stabat Mater” Week 17 Dvorák

2018–19 season andris nelsons bostonmusic director symphony orchestra week 17 dvo rˇ ák “stabat mater” Season Sponsors seiji ozawa music director laureate bernard haitink conductor emeritus supporting sponsorlead sponsor supporting sponsorlead thomas adès artistic partner Better Health, Brighter Future There is more that we can do to help improve people’s lives. Driven by passion to realize this goal, Takeda has been providing society with innovative medicines since our foundation in 1781. Today, we tackle diverse healthcare issues around the world, from prevention to care and cure, but our ambition remains the same: to find new solutions that make a positive difference, and deliver better medicines that help as many people as we can, as soon as we can. With our breadth of expertise and our collective wisdom and experience, Takeda will always be committed to improving the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited future of healthcare. www.takeda.com Takeda is proud to support the Boston Symphony Orchestra Table of Contents | Week 17 7 bso news 1 5 on display in symphony hall 16 bso music director andris nelsons 18 the boston symphony orchestra 2 3 a brief history of the bso 29 casts of character: the symphony statues by caroline taylor 3 6 this week’s program Notes on the Program 38 The Program in Brief… 39 Dvoˇrák “Stabat Mater” 53 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 55 Rachel Willis-Sørensen 57 Violeta Urbana 59 Dmytro Popov 61 Matthew Rose 63 Tanglewood Festival Chorus 65 James Burton 7 0 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 8 3 symphony hall information the friday preview on march 1 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. -

Berlioz: L'enfance Du Christ

LSO Live Berlioz L’enfance du Christ Sir Colin Davis Yann Beuron Karen Cargill William Dazeley Matthew Rose Peter Rose Tenebrae Choir London Symphony Orchestra Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) Page Index L’enfance du Christ (1850–1854) 3 Track listing Words and Music by Hector Berlioz 4 English notes 6 English synopsis 7 French notes 9 French synopsis Yann Beuron tenor The Narrator/Centurion 10 German notes Karen Cargill mezzo-soprano Marie 12 German synopsis William Dazeley baritone Joseph 13 Composer biography Matthew Rose bass Herod 14 Text Part I Peter Rose bass Father/Polydorus 17 Text Part II / Part III Sir Colin Davis conductor 21 Conductor biography London Symphony Orchestra 22 Artist biographies Tenebrae Choir 25 Orchestra and Chorus personnel lists 36 LSO biography Nigel Short choir director Jocelyne Dienst musical assistant James Mallinson producer Daniele Quilleri casting consultant Classic Sound Ltd recording, editing and mastering facilities Jonathan Stokes and Neil Hutchinson for Classic Sound Ltd balance engineers Ian Watson and Jenni Whiteside for Classic Sound Ltd editors A high density DSD (Direct Stream Digital) recording Recorded live at the Barbican, London 2 and 3 December 2006 cover image photograph © Alberto Venzago © 2007 London Symphony Orchestra, London UK P 2007 London Symphony Orchestra, London UK 2 Track listing Track Première Partie, Le Songe d’Hérode / Part One, Herod’s Dream Prologue 1 Dans la crèche, en ce temps (Narrator) 1’53’’ p14 Scene 1 2 Marche Nocturne (Centurion, Polydorus) 8’26’’ p14 Scene 2 3 Toujours -

Sir Colin Davis Discography

1 The Hector Berlioz Website SIR COLIN DAVIS, CH, CBE (25 September 1927 – 14 April 2013) A DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey With special thanks to Philip Stuart © Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey All rights of reproduction reserved [Issue 10, 9 July 2014] 2 DDDISCOGRAPHY FORMAT Year, month and day / Recording location / Recording company (label) Soloist(s), chorus and orchestra RP: = recording producer; BE: = balance engineer Composer / Work LP: vinyl long-playing 33 rpm disc 45: vinyl 7-inch 45 rpm disc [T] = pre-recorded 7½ ips tape MC = pre-recorded stereo music cassette CD= compact disc SACD = Super Audio Compact Disc VHS = Video Cassette LD = Laser Disc DVD = Digital Versatile Disc IIINTRODUCTION This discography began as a draft for the Classical Division, Philips Records in 1980. At that time the late James Burnett was especially helpful in providing dates for the L’Oiseau-Lyre recordings that he produced. More information was obtained from additional paperwork in association with Richard Alston for his book published to celebrate the conductor’s 70 th birthday in 1997. John Hunt’s most valuable discography devoted to the Staatskapelle Dresden was again helpful. Further updating has been undertaken in addition to the generous assistance of Philip Stuart via his LSO discography which he compiled for the Orchestra’s centenary in 2004 and has kept updated. Inevitably there are a number of missing credits for producers and engineers in the earliest years as these facts no longer survive. Additionally some exact dates have not been tracked down. Contents CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF RECORDING ACTIVITY Page 3 INDEX OF COMPOSERS / WORKS Page 125 INDEX OF SOLOISTS Page 137 Notes 1. -

François-Xavier Roth

Sunday 11 November 2018 7–8.55pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT FRANÇOIS-XAVIER ROTH Ligeti Lontano Bartók Cantata profana NELSON Interval Haydn Nelson Mass François-Xavier Roth conductor Camilla Tilling soprano Adèle Charvet mezzo-soprano Julien Behr tenor Matthew Rose bass MASS London Symphony Chorus Simon Halsey chorus director Welcome Latest News On Our Blog I hope you enjoy the performance and THE DONATELLA FLICK LSO DONATELLA FLICK LSO CONDUCTING that you are able to join us again soon. CONDUCTING COMPETITION COMPETITION: THE SHORTLIST This coming Tuesday we present the first of our short, informal Half Six Fix concerts of This month, 20 emerging conductors from Throughout November we’ll be sharing the the season, as François-Xavier Roth conducts across Europe will take part in the 15th stories of the 20 shortlisted contestants Strauss’ instantly recognisable Also sprach Donatella Flick LSO Conducting Competition. vying for the position of LSO Assistant Zarathustra and Debussy’s Prélude à l’après- Across two days of intense preliminary Conductor in the Donatella Flick LSO midi d’un Faune, introducing each work from rounds they’ll compete for the chance to Conducting Competition. the stage. Then on Wednesday we hear a impress our panel of esteemed judges in part repeat of Tuesday’s concert with the the Grand Final here in Barbican Hall on • lso.co.uk/blog addition of Dvořák’s virtuosic Cello Concerto Thursday 22 November. warm welcome to this evening’s with soloist Jean-Guihen Queyras. THE LIFE OF CHARLES SORLEY concert at the -

VINCENZO BELLINI Dyrektor Naczelny Tomasz Bęben Dyrektor Artystyczny Paweł Przytocki Chórmistrz, Szef Chóru Dawid Ber

NORMA VINCENZO BELLINI dyrektor naczelny Tomasz Bęben dyrektor artystyczny Paweł Przytocki chórmistrz, szef chóru Dawid Ber dyrektor generalny Peter Gelb honorowy dyrektor muzyczny James Levine dyrektor muzyczny Yannick Nézet-Séguin główny dyrygent Fabio Luisi 2. Sondra Radvanovsky jako Norma. Fot. Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Prapremiera w Teatro alla Scala w Mediolanie – 26 grudnia 1831 roku Premiera niniejszej inscenizacji w The Metropolitan Opera w Nowym Jorku – 25 września 2017 roku Transmisja z The Metropolitan Opera w Nowym Jorku – 7 października 2017 roku Przedstawienie w języku włoskim z napisami w języku polskim Vincenzo Bellini Norma 3. NORMA OPERA SERIA W DWÓCH AKTACH LIBRETTO: FELICE ROMANI WG ALEKSANDRA SOUNETA OSOBY kapłanka Norma sopran Adalgiza mezzosopran rzymski wódz Pollione tenor kapłan Orowist bas REALIZATORZY reżyseria Sir David McVicar scenografia Robert Jones kostiumy Moritz Junge światło Paule Constable OBSADA Sondra Radvanovsky Norma Joyce DiDonato Adalgiza Joseph Calleja Pollione Matthew Rose Orowist soliści, chór, orkiestra The Metropolitan Opera dyrygent Carlo Rizzi AKCJA ROZGRYWA SIĘ W GALII W 50 R. P.N.E. 4. CARLO RIZZI DYRYGENT Urodzony w 1960 r. w Mediolanie. Dyrygentu- w Hong Kongu i in. W latach 1992-2001 oraz rę studiował u Vladimira Delmana w Bolonii 2004-2008 był dyrektorem Narodowej Opery oraz u Franca Ferrary w Sienie. Zadebiutował Walijskiej. Wśród wielu nagrań Rizziego znajdują w 1982 r. operą G. Donizettiego Opiekun w opa- się Káťa Kabanová L. Janáčka oraz La Traviata łach. Trzy lata później zwyciężył w Konkursie G. Verdiego, zarejestrowana na żywo w czasie Kompozytorskim im. A. Toscaniniego w Parmie. festiwalu w Salzburgu. W The Metropolitan Jego brytyjski debiut miał miejsce w 1988 r. -

Die Meistersinger Von Nürnberg

RICHARD WAGNER die meistersinger von nürnberg conductor Opera in three acts James Levine Libretto by the composer production Otto Schenk Saturday, December 13, 2014 12:00–6:00 PM set designer Günther Schneider-Siemssen costume designer Rolf Langenfass lighting designer Gil Wechsler choreographer The production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg Carmen De Lavallade is made possible by a generous gift from stage director Mrs. Donald D. Harrington Paula Suozzi The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Corbin R. Miller and Mr. and Mrs. Charles Scribner III, in honor of Father Owen Lee general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine principal conductor Fabio Luisi The 413th Metropolitan Opera performance of RICHARD WAGNER’S This performance die meistersinger is being broadcast live over The von nürnberg Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, conductor America’s luxury James Levine ® homebuilder , with in order of vocal appearance generous long-term support from walther von stol zing, konr ad nachtigall, tinsmith The Annenberg a knight from fr anconia John Moore* Johan Botha° Foundation, The fritz kothner, baker Neubauer Family eva, pogner’s daughter Martin Gantner Foundation, the Annette Dasch Vincent A. Stabile hermann ortel, soap-maker Endowment for magdalene, her at tendant David Crawford Broadcast Media, Karen Cargill balthasar zorn, pew terer and contributions David Cangelosi from listeners david, apprentice to sachs worldwide. Paul Appleby* augustin moser, tailor veit pogner, goldsmith Noah Baetge Visit List Hall at the Hans-Peter König second intermission ulrich eisslinger, grocer Tony Stevenson* for the Toll Brothers– six tus beckmesser, Metropolitan Opera town clerk hans foltz, coppersmith Quiz. -

THE METROPOLITAN OPERA Subject to Change 2019-20 TOLL BROTHERS-METROPOLITAN OPERA INTERNATIONAL RADIO NETWORK SEASON As of 2/20/2019

THE METROPOLITAN OPERA Subject to change 2019-20 TOLL BROTHERS-METROPOLITAN OPERA INTERNATIONAL RADIO NETWORK SEASON as of 2/20/2019 On- Off- Delay Delay Last Date Opera INT Air Air start end Broadcast 2019 October 12 TURANDOT (Puccini) 1:00 4:22 2 3/24/2018 HD** Yannick Nézet-Séguin; Christine Goerke (Turandot), Eleonora Buratto (Liù), Roberto Aronica (Calàf), James Morris (Timur) October 26 MANON (Massenet) Maurizio Benini; Lisette Oropesa (Manon), Michael Fabiano (Chevalier des Grieux), Carlo Bosi (Guillot de Morfontaine), 1:00 5:12 2 3/21/2015 HD** Artur Ruciński (Lescaut), Brett Polegato (de Brétigny), Kwangchul Youn (Comte des Grieux) November 9 MADAMA BUTTERFLY (Puccini) 1:00 4:32 2 3/3/2018 HD** Pier Giorgio Morandi; Hui He (Cio-Cio-San), Elizabeth DeShong (Suzuki), Andrea Carè (Pinkerton), Plácido Domingo (Sharpless) November 23 AKHNATEN (Philip Glass) – New Production/Met Premiere Network Karen Kamensek; Dísella Lárusdóttir (Queen Tye), J'nai Bridges (Nefertiti), Anthony Roth Costanzo (Akhnaten), 1:00 4:56 2 HD** Premiere Aaron Blake (High Priest of Amon), Will Liverman (Horemhab), Richard Bernstein (Aye), Zachary James (Amenhotep) December 7 AKHNATEN (Philip Glass) – New Production/Met Premiere Network Karen Kamensek; Dísella Lárusdóttir (Queen Tye), J'nai Bridges (Nefertiti), Anthony Roth Costanzo (Akhnaten), 1:00 4:45 2 First SatMat Premiere Aaron Blake (High Priest of Amon), Will Liverman (Horemhab), Richard Bernstein (Aye), Zachary James (Amenhotep) December 14 THE QUEEN OF SPADES (Tchaikovsky) Vasily Petrenko; Lise Davidsen