Jazz Experimentalism in Germany, 1950–1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

1 Konzertkritiken, Programme, Flyer U.Ä. 1.1 (Vorwiegend)

- 2 - 1 Konzertkritiken, Programme, Flyer u.ä. 1.1 (vorwiegend) Programme, Flyer u.ä. AM-1-A/84 Konzertprogramme, Flyer, diverse Drucksachen zum Jazz Enthält u.a.: Dizzy Gillespie, King of Bepop, o. J. der drummer. Herausgeg. von Sonor-Werke. Frankfurt, 1953, Nr. 1 der drummer. VI. deutsches jazz-festival. Herausgeg. von Sonor-Werke. Frankfurt, [1958] hans kollers new jazz group, Köln, 22.3.1954 Jazz 1956 (Programm der Deutschen Jazz-Föderation) REPORT. Mitteilungen des New Jazz-Circle Berlin e.V., Dez. 1958 hans kollers new Jazz stars, 1958 Teatro Sociale, Mantua, 23.2.1959 jazzforum (5 jahre jazzstudio nürnberg ev). Nürnberg, 1959 Mai Festival du Jazz, 2.8.1959 1953 - 1959 AM-1-A/82 Programmhefte, Flyer, Einladungen, diverse Drucksachen zu Frankfurter Jazzveranstaltung Enthält u.a.: - "Jazz 1956" und "Jazz 1958"; - Deutsches Jazz Festival, 4./1956, 7./1960, 12./1970, 15./1976, 22./1990; - 16 Jahre Hot Club Ffm, 6 Jahre Domicile du Jazz. (Programm der Jubiläumswoche, Faltblatt), 9.-15.9.1957 - Konzert in Jazz. Albert-Mangelsdorff-Quintett. (Programmzettel für ein Konzert im Haus Ronneburg), 8.9.1962 - Lieder im Park (Günthersburgpark), 1975 f.; - 1952-1977. 25 Jahre "der jazzkeller" Frankfurt. Festschrift, herausgeg. von Willi Geipel, 1977 1956 - 2003 AM-1-A/16 Jazz-Konzerte und Tourneen Enthält v.a.: Programme, Flyer, vereinzelte Kritiken ca. 1960-1969 unsortiert AM-1-A/18 Jazz-Konzerte und Tourneen Enthält v.a.: Presseartikel, Kritiken, Programme, Flyer ca. 1960-1969 ungeordnet AM-1-A/80 Programmhefte, Flyer, Einladungen, diverse Drucksachen zu Jazzveranstaltung Enthält u.a.: Jazz "Solo now!", Asien-Tournee (Jakarta) "Solo now!", 5 Jahre Jazzclub Hannover; 2. -

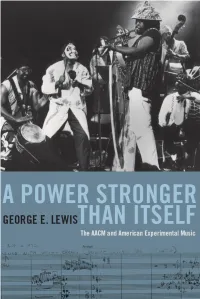

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY -

Konnex-Katalog 51Xx

Konnex-Katalog 51xx KCD 5100 EUROPEAN JAZZ ENSEMBLE "25th Anniversary Tour" CHARLIE MARIANO, JOACHIM KÜHN, PAOLO FRESU, CONNY BAUER, JARMO HOOGENDIJK, ALLAN BOTSCHINSKY, ALAN SKIDMORE, JIRI STIVIN, STAN SULZMAN, GERD DUDEK, ROB VAN DEN BROECK, ADELHARD ROIDINGER, ALI HAURAND, TONY LEVIN & DANIEL HUMAIR KCD 5102 “Surface” HOLGER MANTEY piano, MATHIAS SCHUBERT tenor sax KCD 5103 ORGANIZED CHAOS PETER BROETZMANN tenor sax, tarogato, e-flat clarinet, bass sax NICKY SKOPELITIS e lectric guitar SHOJI HANO drums KCD 5104 ORANGE TOWN WOLFGANG SCHLUETER marimba & vibraphone CHRISTOPH SPENDEL piano KCD 5105 EUROPLOSION ACHIM JAROSCHEK piano & MANI NEUMEIER perc. KCD 5106 DAS ROSA RAUSCHEN II FELIX WAHNSCHAFFE alto sax, JOHN SCHRÖDER guitar OLIVER POTRATZ bass, ERIC SCHAEFER drums KCD 5108 SCHINDERKARREN MIT BUFFET “Jazz & Lyrik” PAUL EßER narration, GERD DUDEK sax, JIRI STIVIN flutes, clarinet, ALI HAURAND bass KCD 5109 WOKONDA ACHIM JAROSCHEK piano GÜNTER „BABY” SOMMER persusion KCD 5110 FRONTIER TRAFFIC MARIANO alto sax, ALI HAURAND bass, DANIEL HUMAIR drums KCD 5111 DUBBEL DUO ANDRE GOUDBEEK saxes, PETER JACQUEMYN bass PETER KOWALD bass, JEFFREY MORGAN saxes KCD 5112 AHOI THORSTEN KLENTZE guitar, JOST HECKER cello, ROGER JANOTTA saxes, MARIKA FALK percussion KCD 5113 ERNST BIER/MACK GOLDSBURY QUARTET MACK GOLDSBURY saxes, HERB ROBERTSON trumpet MATTHIAS BAETZEL hammond organ, ERNST BIER drums KCD 5115 TAKE NO PRISONERS BERT WILSON saxes, JEFFREY MORGAN piano KCD 5114 ASAF SIRKIS & INNER NOISE STEVE LODDER church organ, MIKE OUTRAM guitar ASAF -

Swr2-Musikstunde-20120830.Pdf

___________________________________________________________________ Signet SWR2 Musikstunde 1 AT „Ich höre alles außer Free Jazz“: So eine Antwort bekommt man nicht selten, wenn man Menschen nach ihrem Musikgeschmack befragt und diese Gefragten mit ihrer Aussage gleich unmissverständlich zwei Dinge klar stellen wollen: 1. Ich bin wahnsinnig offen, deswegen gefällt mir vieles. 2. Ich kann Krach von Klang unterscheiden, deswegen weiß ich, dass Free Jazz eigentlich keine Musik ist. Und natürlich schon gar kein Jazz. {00:25} Musik 1 T: Accident Happening K: Ken Vandermark I: The Vandermark 5 CD: Burn the incline ALP 121, kein LC {00:17} 2 AT Es scheint immer noch zum guten Ton zu gehören, auch unter ansonsten neugierigen, aufgeklärten, toleranten Kultur-Freundinnen und -Freunden, sich gegenseitig die Ungenießbarkeit des Free Jazz zu bestätigen. Einige Unterschriften für Folgendes kämen jedenfalls sicher ziemlich schnell zusammen: „Vor kurzen hörte ich ... einer furchteinflößenden Demonstration dessen zu, was ein wachsender Antijazz-Trend zu werden beginnt, ausgeführt von den ersten Verfechtern einer Musik, die man Avantgarde nennt.“ Knapp fünfzig Jahre alt ist diese Bemerkung eines amerikanischen Jazzkritikers – erschienen wohlgemerkt im Down-Beat, einem der seriösesten Jazzmagazine überhaupt. Interessanterweise fast im selben Wortlaut argumentiert auch im Jahr 2010 noch der „Ich höre alles, außer Free Jazz“-Bekenner 2 gegen eine Musik, der die Jazzpolizei im Verlaufe ihrer Geschichte immer wieder gerne Strafzettel verpasst hat. Bußgeld gibt es dafür heute von uns nicht, dafür: Achtung! durchaus ein paar wuchtige Free Jazz Klänge. Aber – wir tasten uns langsam an sie heran. Und das hier – ist noch keiner: {01:15} Musik 2 T: So What (bis Ende Solo Coltrane) K: Miles Davis I: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Julian Cannonball Adderly, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers, Jimmy Cobb CD: Kind of Blue CK 64935, LC 0162 {05:15} 3 AT Auch wenn das sehr unhöflich ist – an dieser Stelle muss Cannonball Adderly sein Solo heute frühzeitig beenden. -

Johannes Bauer

Johannes Bauer Discography | Diskographie 15.03.2019 2019 – 03 Zlatko Kaucic – Diversity Not Two Records, MW 969-2 Not Two Records, MW 969-2 Zlatko Kaučič – Ground Drums, Percussion Johannes Bauer – Trombone CD#5 »MED-ANA« 1. Med-Ana – 11:34 / 2. Med-Ana – 3:34 / 3. Med-Ana – 8:21 / 4. Med-Ana – 8:52 / 5. Med-Ana – 2:53 / 6. Šmartno Suita – 23:55 Tracks 1 to 5 – Recorded at Medana “Old Movie Theatre” on September 15, 2012. Track 6 – Recorded at Brda Contemporary Music Festival, Italy on September 13, 2014. 5 CDs in single printed paper-sleeves housed in a sturdy cardboard box-set with a magnetic locking. Contains a 12-page booklet with an interview, line-ups, liner notes and photographs. Only CD #5 with Johannes. 2018 – 01 Jeb Bishop, Matthias Müller, Matthias Muche – Konzert für Hannes Not Two Records, MW 961-2 Jeb Bishop – trombone Matthias Müller – trombone Matthias Muche – trombone 1. 07:39 / 2. 06:07 / 3. 09:03 / 4. 07.59 / 5. 07:40 / 6. 07:09 Recorded live at Stadtgarten Köln on May 5th 2016 Tribut Recording Johannes Bauer Discography 2 | 44 2017 – 01 Johannes Bauer / Peter Broetzmann – Blue City Trost Records, TR155 Peter Brötzmann: tenor & alt sax, tarogato, b-flat clarinet Johannes Bauer: trombone 1 Name That Thing 28:42 2 Blue City 5:11 3 Poppy Cock 15:25 4 Heard And Seen 14:05 5 Hot Mess 6:10 Mastered By – Martin Siewer, Photography – Philippe Renaud Live at Blue City Osaka / Japan 16. October 1997 2014 – 02 Barry Guy New Orchestra Small Formations – Mad Dogs On The Loose Not Two Records , MW925-2, 4 × CD, Album Barry Guy bass -

JNM 06 18 01 Cover Wolfgang Muthspiel Lay.Indd 1 29.10.18 09:53 Helvetia.Ch/Wertsachen

Das Schweizer Jazz & Blues Magazin Nov./Dez. N r . 6 /2018 S Schweiz CHF 11.00 / Deutschland € 5.90 / Österreich € 6.10 , ROOT ‚ N BLUES ‘RE‘RENN 'M'MOO WAYNE SHORTER DIANA KRALL/ TONY BENNETT SIMON SPIESS RONIN LABEL ANTHONY BRAXTON/ GERRY HEMINGWAY KAOS PROTOKOLL MUD MORGANFIELD GENE PERLA OM FRANCO AMBROSETTI DAVE KEYES GÜNTER BABY SOMMER TOMAS SAUTER FEE STRACKE WOLFGANG PETER SCHÄRLI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN MUTHSPIEL RICCARDO DEL FRA WHERE THE RIVER GOES MANUEL TROLLER SPECIAL: JAZZHOCHSCHULEN DER SCHWEIZ JNM_06_18_01_Cover_Wolfgang Muthspiel_lay.indd 1 29.10.18 09:53 helvetia.ch/wertsachen Les Paul. Stratocaster. Keine Misstöne. FI_CH_CC_INS_JazzNmore_A4_18-10.inddJNM_06_18_02-03_EDI_Inhalt.indd 2 1 22.10.1829.10.18 22:0110:15 EDITORIAL INHALT Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, 3 Editorial/Inhalt/Impressum 4 Flashes bereits wieder haltet Ihr die letzte Ausgabe des Jahres in 7 REVIEWS 14 PREVIEWS den Händen und ich hoffe, wir konnten im vergangenen Jahr 20 WOLFGANG Muthspiel – Where The River GOES erneut mit vielen interessanten Interviews und Geschichten, 23 Promo: Helvetia Versicherung den unzähligen CD-Besprechungen und "News you can use" 24 WAYNE Shorter dem Anspruch als modernes und zeitgemässes Jazz & Blues 27 OM Magazin gerecht werden. 28 Diana Krall/TonY Bennett 30 GÜnter BabY Sommer 32 SimoN SPIESS Auch die vorliegende Ausgabe bietet viel Spannendes. Die 33 Special: Jazzhochschulen DER Schweiz Coverstory von Steff Rohrbach präsentiert den Ausnahme- gitarristen Wolfgang Muthspiel, der soeben sein neues Album 57 NEW PROJECTS: Franco Ambrosetti – Peter Schärli – auf ECM veröffentlicht hat; Jürg Solothurnmann beschreibt Kaos Protokoll – Fee Stracke – Tomas Sauter – die unge brochene Schaffenskraft des 85-jährigen Wayne Manuel Troller – Riccardo Del Fra Shorter und sein neustes Werk "Emanon"; Günter Baby Som- BLUES’N’roots mer wird anlässlich seines 75. -

Discographie

CHRISTIAN SCHOLZ UNTERSUCHUNGEN ZUR GESCHICHTE UND TYPOLOGIE DER LAUTPOESIE Teil III Discographie GERTRAUD SCHOLZ VERLAG OBERMICHELBACH (C) Copyright Gertraud Scholz Verlag, Obermichelbach 1989 ISBN 3-925599-04-5 (Gesamtwerk) 3-925599-01-0 (Teil I) 3-925599-02-9 (Teil II) 3-925599-03-7 (Teil III) [849] INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. PRIMÄRLITERATUR 389 [850] 1. ANTHOLOGIEN 389 [850] 2. VORFORMEN 395 [865] 3. AUTOREN 395 [866] II. SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR 439 [972] III. HÖRSPIELE 452 [1010] ANHANG 460 [1028] IV. VOKALKOMPOSITIONEN 460 [1029] V. NACHWORT 471 [1060] [850] I. PRIMÄRLITERATUR 1. ANTHOLOGIEN Absolut CD # 1. New Music Canada. A salute to Canadian composers and performers from coast to coast. Ed. by David LL Laskin. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von Hildegard Westerkamp u. a. CD Absolut CD # 2. The Japanese Perspective. Ed. by David LL Laskin. Special Guest Editor: Toshie Kakinuma. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von Yamatsuka Eye & John Zorn, Ushio Torikai u. a. CD Absolut CD # 3. Improvisation/Composition. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von David Moss, Joan La Barbara u. a. CD The Aerial. A Journal in Sound. Santa Fe, NM, USA: Nonsequitur Foundation 1990, Nr. 1, Winter 1990. AER 1990/1. Mit Beiträgen von David Moss, Malcolm Goldstein, Floating Concrete Octopus, Richard Kostelanetz u. a. CD The Aerial. Santa Fe, NM, USA: Nonsequitur 1990, Nr. 2, Spring 1990. AER 1990/2. Mit Beiträgen von Jin Hi Kim, Annea Lockwood, Hildegard Westerkamp u. a. CD The Aerial. -

Free Music Production FMP: the Living Music

HAUS DER KUNST Free Music Production FMP: The Living Music STRETCH YOUR VIEW Einführung DE Diese Ausstellung widmet sich der Geschichte des Die Ausstellung dokumentiert in noch nicht dagewesenem Musiklabels Free Music Production (FMP), das von 1968 Umfang mithilfe von Fotografien, Postern, Flyern, Ori- bis 2010 als Berliner Plattform für die Produktion, Präsen- ginaldokumenten, Interviews sowie vielen noch nie zuvor tation und Dokumentation von Musik Unvergleichliches gesehen dokumentarischen Videos und bisher unveröffent- geleistet hat. Seit den späten 1950er-Jahren hatte es immer lichten Aufnahmen aus dem FMP-Archiv von Jost Gebers die 1 wieder Versuche von Musikern gegeben, ihre Produktions- verschiedenen FMP-Formate und stellt zudem auch die gesamte und Arbeitsbedingungen selbstbestimmt zu gestalten. So- Tonträgerproduktion vor. wohl in ihrer Langlebigkeit als auch in der Vielfältigkeit ihrer Unternehmungen ist die FMP bis heute einzigartig Heute, kurz vor dem 50-jährigen Jubiläum der FMP, wird klar, und in dieser Form vielleicht nur in Westberlin möglich dass die Free Music Production durch ihre Konsequenz und gewesen. ihre Öffnung für viele verschiedene Musiken und kulturelle Praktiken aus aller Welt zu den wesentlichsten kulturhis- Weil der Saxofonist Peter Brötzmann den Veranstaltern der torischen Beiträgen gehört, die Westberlin zur Kunst- und Berliner Jazztage (heute Jazzfest Berlin) nicht garantieren Kulturgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts geleistet hat. konnte, dass seine Gruppe in schwarzen Anzügen auftreten würde, und deshalb wieder ausgeladen wurde, organisierte er 1968 zusammen mit dem Bassisten Jost Gebers das erste Total Music Meeting (TMM). Wie schon zuvor in den Musikszenen der Vereinigten Staaten, ging es auch bei dieser Initia- tive darum, die Arbeitsbedingungen für junge Musiker zu ver- bessern. -

Jazz Experimentalism in Germany, 1950-1975

European Echoes: Jazz Experimentalism in Germany, 1950-1975 Harald Kisiedu Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Harald Kisiedu All rights reserved ABSTRACT “European Echoes: Jazz Experimentalism in Germany, 1950-1975” Harald Kisiedu “European Echoes: Jazz Experimentalism in Germany, 1950-1975” is a historical and interpretive study of jazz and improvised music in West and East Germany. “European Echoes” illuminates an important period in German jazz whose beginnings are commonly associated with the notion of Die Emanzipation (“The Emancipation”). Standard narratives of this period have portrayed Die Emanzipation as a process in which mid-1960s European jazz musicians came into their own by severing ties of influence to their African American musical forebears. I complicate this framing by arguing that engagement with black musical methods, concepts, and practices remained significant to the early years of German jazz experimentalism. Through a combination of oral histories, press reception, sound recordings, and archival research, I elucidate how local transpositions and adaptations of black musical methods, concepts, and practices in post-war Germany helped to create a prime site for contesting definitions of cultural, national, and ethnic identities across Europe. Using a case study approach, I focus on the lives and works of five of the foremost German jazz experimentalists: multi-reedist Peter Brötzmann, trumpeter and composer Manfred Schoof, pianist and composer Alexander von Schlippenbach, multi-reedist Ernst-Ludwig Petrowsky, and pianist Ulrich Gumpert. Furthermore, I discuss new music composer Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s sustained engagement with African American musical forms in addition to the significance of both Schoof’s and Schlippenbach’s studies and various collaborations with him. -

Programmvorschau 11

Programmvorschau 11. bis 17. Februar 2019 7. Mitschnitt Die mit gekennzeichneten Sendungen sind für private Zwecke ausschließlich gegen Rechnung, unter Angabe von Name und Adresse für 10,– Euro erhältlich bei: Deutschlandradio Service GmbH, Hörerservice Raderberggürtel 40, 50968 Köln Weitere Informationen erhalten Sie unter Telefon 0221 345-1847 deutschlandradio.de Hörerservice Telefon 0221 345-1831 Telefax 0221 345-1839 [email protected] 1 Programmerläuterungen siehe Anhang Mo 11. Feb 0.00 Nachrichten 9.00 Nachrichten 20.00 Nachrichten 0.05 Deutschlandfunk Radionacht 9.05 Kalenderblatt 20.10 Musikjournal 0.05 Fazit Vor 150 Jahren: Das Klassik-Magazin Kultur vom Tage Die Dichterin Else Lasker-Schüler 21.00 Nachrichten (Wdh.) geboren 21.05 Musik-Panorama 1.00 Nachrichten 9.10 Europa heute Maßlos frei 1.05 Kalenderblatt 9.30 Nachrichten ☛ Das Kölner ensemble 20/21 spielt 1.10 Interview der Woche 9.35 Tag für Tag neue Musik aus Japan (Wdh.) Aus Religion und Gesellschaft Werke von 1.35 Hintergrund 10.00 Nachrichten (Wdh.) 10.10 Kontrovers TÔRU TAKEMITSU, 2.00 Nachrichten Politisches Streitgespräch mit SUZUKI HARUYUKI, 2.05 Sternzeit Studiogästen und Hörern MAYAKO KUBO, 2.07 Kulturfragen Hörertel.: 0 08 00-44 64 44 64 MISATO MOCHIZUKI, Debatten und Dokumente [email protected] DOI CHIEKO, (Wdh.) 10.30 Nachrichten TOSHIO HOSOKAWA anschließend ca. 11.00 Nachrichten Aufnahme vom 25.1.2019 aus dem 2.30 Zwischentöne 11.30 Nachrichten Japanischen Kulturinstitut Köln Musik und Fragen zur Person 11.35 Umwelt und Verbraucher -

Recorded Jazz in the Early 21St Century

Recorded Jazz in the Early 21st Century: A Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull. Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 The Consumer Guide: People....................................................................................................................7 The Consumer Guide: Groups................................................................................................................119 Reissues and Vault Music.......................................................................................................................139 Introduction: 1 Introduction This book exists because Robert Christgau asked me to write a Jazz Consumer Guide column for the Village Voice. As Music Editor for the Voice, he had come up with the Consumer Guide format back in 1969. His original format was twenty records, each accorded a single-paragraph review ending with a letter grade. His domain was rock and roll, but his taste and interests ranged widely, so his CGs regularly featured country, blues, folk, reggae, jazz, and later world (especially African), hip-hop, and electronica. Aside from two years off working for Newsday (when his Consumer Guide was published monthly in Creem), the Voice published his columns more-or-less monthly up to 2006, when new owners purged most of the Senior Editors. Since then he's continued writing in the format for a series of Webzines -- MSN Music, Medium,