Judith Bernstein Selected Press Pa Ul Kasmin Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere Something Possible

NYC 1983–84 NYC PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere Something Possible PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere NYC 1983–84 PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere NYC 1983–84 Jane Bauman PIER 34 Mike Bidlo Something Possible Everywhere Paolo Buggiani NYC 1983–84 Keith Davis Steve Doughton John Fekner David Finn Jean Foos Luis Frangella Valeriy Gerlovin Judy Glantzman Peter Hujar Alain Jacquet Kim Jones Rob Jones Stephen Lack September 30–November 20 Marisela La Grave Opening reception: September 29, 7–9pm Liz-N-Val Curated by Jonathan Weinberg Bill Mutter Featuring photographs by Andreas Sterzing Michael Ottersen Organized by the Hunter College Art Galleries Rick Prol Dirk Rowntree Russell Sharon Kiki Smith Huck Snyder 205 Hudson Street Andreas Sterzing New York, New York Betty Tompkins Hours: Wednesday–Sunday, 1–6pm Peter White David Wojnarowicz Teres Wylder Rhonda Zwillinger Andreas Sterzing, Pier 34 & Pier 32, View from Hudson River, 1983 FOREWORD This exhibition catalogue celebrates the moment, thirty-three This exhibition would not have been made possible without years ago, when a group of artists trespassed on a city-owned the generous support provided by Carol and Arthur Goldberg, Joan building on Pier 34 and turned it into an illicit museum and and Charles Lazarus, Dorothy Lichtenstein, and an anonymous incubator for new art. It is particularly fitting that the 205 donor. Furthermore, we could not have realized the show without Hudson Gallery hosts this show given its proximity to where the the collaboration of its many generous lenders: Allan Bealy and terminal building once stood, just four blocks from 205 Hudson Sheila Keenan of Benzene Magazine; Hal Bromm Gallery and Hal Street. -

Ray Johnson Drawings and Silhouettes, 1976-1990. RJE.FA02L.2012 RJE.01.2012 Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared by Julia Lipkins

Ray Johnson drawings and silhouettes, 1976-1990. RJE.FA02L.2012 RJE.01.2012 Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Julia Lipkins This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit August 18, 2015 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Ray Johnson Estate January 2013 34 East 69th Street New York, NY, 10021 (212) 628-0700 [email protected] Ray Johnson drawings and silhouettes, 1976-1990. RJE.FA02L.2012 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents Note.............................................................................................................................. 4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

Available in 12 Styles Licenses for Web, Desktop, & App Designed By

Garnett Designed by Available in 12 styles Connor Davenport in 2018 Licenses for Web, Desktop, & App 1 All Caps Roman POWERS Black — 70pt BURMAN Bold — 70pt KNIGHTS Semibold — 70pt BERKSOY Medium — 70pt CHRYSSA Regular — 70pt VELASCO Light — 70pt Garnett 2 All Caps Italic MÜNTER Black Italic — 70pt PARRISH Bold Italic — 70pt REYNELL Semibold Italic — 70pt STECKEL Medium Italic — 70pt ANSINGH Regular Italic — 70pt KAY SAGE Light Italic — 70pt Garnett 3 Title Case Roman Spanton Black — 70pt Léontine Bold — 70pt Bagshaw Semibold — 70pt Kostenko Medium — 70pt Schwartz Regular — 70pt Nimarkoh Light — 70pt Garnett 4 Title Case Italic Winegar Black Italic — 70pt Blumann Bold Italic — 70pt Käsebier Semibold Italic — 70pt Mendieta Medium Italic — 70pt Chalmers Regular Italic — 70pt Suruzhon Light Italic — 70pt Garnett 5 All Caps & Title Case Roman MOTHER AND CHILD Sanja Iveković Black — 30pt BRAZILIAN ORCHIDS Henriette Wyeth Bold — 30pt I DON’T KNOW WHAT Mary Tillman Smith Semibold — 30pt STATUE DE CAVALIER Émilie Charmy Medium — 30pt IN THE BOX, VERTICAL Ruth Bernhard Regular — 30pt BLUE ATMOSPHERE III Helen Frankenthaler Light — 30pt Garnett 6 All Caps & Title Case Italic FREEING THE VOICE Marina Abramović Black — 30pt JEAN-PAUL SARTRE Gisèle Freund Bold — 30pt MUSIQUE ADORABLE Valentine Hugo Semibold — 30pt THE CRY OF ORESTES Françoise Gilot Medium — 30pt THE NIGHT SWIMMER Brita Granström Regular — 30pt EAST TENTH STREET Anne Goldthwaite Light — 30pt Garnett 7 Text Sizes, Mixed Weights 18pt / 23 ‒ Mixed Weights In 1905, Georgia O’Keeffebegan her serious formal art training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and then the Art Students League of New York, but she felt constrained by her lessons that focused on recreating or copying what was in nature. -

Deborah Kass & Betty Tompkins

“FRONTRUNNER Presents: Deborah Kass & Betty Tompkins,” by Shana Beth Mason for Frontrunner, January 29, 2021. FRONTRUNNER Presents: Deborah Kass & Betty Tompkins At one point or another within the last ten years, I’ve laughed, cried, gossiped and shared meals with Betty Tompkins (alongside her husband, Bill Mutter) and Deborah Kass (alongside her wife, Patricia Cronin). So it’s fair to say that both of these women mean a great deal to me. They are not only world-renowned artists who have been cruelly under-represented and under-appreciated for most of their creative lives, but they are true mentors in every sense. Their experiences and their wisdom are windows into an art world long gone – for many reasons, rightly so – and have deeply permeated their respective visual vocabularies. Deborah Kass (b. 1952, San Antonio, TX) received her BFA in Painting at Carnegie Mellon University and attended the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program. Her works are in the permanent collections of MoMA, The Whitney Museum, The National Portrait Gallery (Washington, D.C.), The Smithsonian Institution, and The Jewish Museum (New York). She has presented work at the Venice Biennale, the Istanbul Biennale, and in 2012 was the subject of a mid-career retrospective at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. She is currently a Senior Critic at the Yale University MFA Painting Program. Kass is represented by Gavlak Gallery (Los Angeles/Palm Beach) and Kavi Gupta (Chicago). Betty Tompkins (b. 1945, Washington, D.C.) received her BFA from Syracuse University, then taught at Central Washington State College (Ellensburg), where she received her graduate degree. -

Betty Tompkins

The Drawers - Headbones Gallery Contemporary Drawing, Sculpture and Works on Paper Revivified April 3 - April 29, 2008 Betty Tompkins Commentary by Julie Oakes Artist Catalog, Betty Tompkins Copyright © 2008, Headbones Gallery This catalog was created for the exhibition titled “Revivified” at Headbones Gallery, The Drawers, Toronto, Canada, April 3 - April 29, 2008 Commentary by Julie Oakes Copyright © 2008, Julie Oakes Artwork Copyright © 1995 -1999, Betty Tompkins Rich Fog Micro Publishing, printed in Toronto, 2008 Layout and Design, Richard Fogarty Courtesy Mitchell Algus Gallery, New York Printed on the Ricoh SPC 811DN All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 copyright act or in writing from Headbones Gallery. Requests for permission to use these images should be addressed in writing to Betty Tompkins, c/o Headbones Gallery. www.headbonesgallery.com RICH FOG Micro Publishing Toronto Canada Betty Tompkins Revivified Did the frolic come first or the spring in which to frolic? In Tompkins' impressionist paintings on photographic images, women from the 30's and 40's saucily act out in a frothy, leafy, grassy, effulgent playground, like nymphs in a naturalist boudoir. In contrasting colors, where the red next to green or fuchsia beside puce is as vibrant as a gift wrapped with the freshness of nature; Betty Tompkins' pin-ups from the past cavort in the outdoors. Like a flurry of covert caresses between viridian landscapes and scantily clad figures, tantalizing fleshy hues are discretely muted by the photographic gradations from white to black as they lay in the arms of pastel bushiness. -

17 JUDITH BERNSTEIN Interviewed by Jonathan Thomas

JUDITH BERNSTEIN interviewed by Jonathan Thomas Judith Bernstein, Rising, installation view: Studio Voltaire, 2014 Jonathan Thomas: It’s snowing—and of women. I was very much aware of the fact there’s a parade outside. that there were only three women in my class Judith Bernstein: Yes, it’s a good omen; and that the rest were men. The instructors we’ve started on the Chinese New Year! were all men, except for Helen Frankenthaler, Thomas: Okay, this sounds a bit crazy. who was a visiting instructor and only taught a Bernstein: I see, there’s a disclaimer single course. At the orientation address, Jack already. What’s going on here? Tworkov, who was Chair of the School of Art, Thomas: I was going to say that for its said We cannot place women. What he meant to first 268 years, Yale University only accepted say was, If you’re a woman, you’re on your own students if they were men. after you graduate. We can’t help you get a job Bernstein: That’s correct. in an academic setting. That was day one, but Thomas: So when you were there as a it just went in one ear and out the other. Times graduate student from 1964 to 1967, women have changed. Now there are more women at were not permitted to attend as undergradu- Yale than men. ates, only men. That changed in 1969, but I’m Thomas: And the cost of getting an MFA wondering what it was like for you as a student has changed too. -

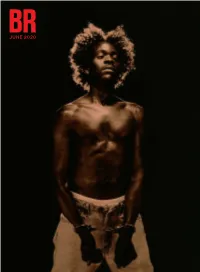

June 2020 June 2020 June 2020 June 2020

JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 field notes art books Normality is Death by Jacob Blumenfeld 6 Greta Rainbow on Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects 88 Where Is She? by Soledad Álvarez Velasco 7 Kate Silzer on Excerpts from the1971 Journal of Prison in the Virus Time by Keith “Malik” Washington 10 Rosemary Mayer 88 Higher Education and the Remaking of the Working Class Megan N. Liberty on Dayanita Singh’s by Gary Roth 11 Zakir Hussain Maquette 89 The pandemics of interpretation by John W. W. Zeiser 15 Jennie Waldow on The Outwardness of Art: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes 90 Propaganda and Mutual Aid in the time of COVID-19 by Andreas Petrossiants 17 Class Power on Zero-Hours by Jarrod Shanahan 19 books Weston Cutter on Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League art and Luke Geddes’s Heart of Junk 91 John Domini on Joyelle McSweeney’s Toxicon and Arachne ART IN CONVERSATION and Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s Seeing the Body: Poems 92 LYLE ASHTON HARRIS with McKenzie Wark 22 Yvonne C. Garrett on Camille A. Collins’s ART IN CONVERSATION The Exene Chronicles 93 LAUREN BON with Phong H. Bui 28 Yvonne C. Garrett on Kathy Valentine’s All I Ever Wanted 93 ART IN CONVERSATION JOHN ELDERFIELD with Terry Winters 36 IN CONVERSATION Jason Schneiderman with Tony Leuzzi 94 ART IN CONVERSATION MINJUNG KIM with Helen Lee 46 Joseph Peschel on Lily Tuck’s Heathcliff Redux: A Novella and Stories 96 june 2020 THE MUSEUM DIRECTORS PENNY ARCADE with Nick Bennett 52 IN CONVERSATION Ben Tanzer with Five Debut Authors 97 IN CONVERSATION Nick Flynn with Elizabeth Trundle 100 critics page IN CONVERSATION Clifford Thompson with David Winner 102 TOM MCGLYNN The Mirror Displaced: Artists Writing on Art 58 music David Rhodes: An Artist Writing 60 IN CONVERSATION Keith Rowe with Todd B. -

Artforum Fusco January 30, 2007

http://www.artforum.com/diary/1 01.30.07 Gender Bender New York · Rhonda Lieberman on feminism at MoMA · Andrew Berardini around Los Angeles · William Pym on Philadelphia's biggest-ever art party Left: Coco Fusco and the Guerrilla Girls. (Photo: Brian Sholis) Right: Curator Catherine · David Velasco on de Zegher and artist Martha Rosler. (Photo: David Velasco) Terence Koh at the Whitney On Friday, I attended the first half of a two-day symposium at MoMA · Lillian Davies on on “The Feminist Future: Theory and Practice in the Visual Arts.” The Tim Gardner at the sold-out Roy and Niuta Titus Theater was packed with vintage women National Gallery artists, as well as chroniclers, comrades, and frenemies, whether they · Zach Baron at identified with the “f-word” or not. Thankfully, not much time was concerts by Patti wasted quibbling over that, as is customary in such situations, though Smith and Text of Light one questioner did complain about the “c-word,” which she found as deeply offensive as the “n-word.” The lady next to me wondered, “What’s the N-word?” Oy. I helpfully wrote it on her program. She later January 2007 crossed it out. December 2006 The day started with palpable excitement. It seemed a roomful of November 2006 underacknowledged women artists were about to taste vindication at October 2006 MoMA, the stern, withholding mothership. The venerable Lucy Lippard September 2006 kicked things off with a minihistory of our struggles, contrasting early feminist ideals of community and revolution with the more cynical August 2006 early-twenty-first-century careerism. -

Cunt, Slut, Bitch, Mother Betty Tompkins, Interviewed By

Cunt, slut, bitch, mother was 2% that she thought was really misogynist and caricatured both men and women. [Heigl Betty Tompkins, interviewed by Elliat Albrecht was quoted as saying the that film “paints the women as shrews, as humourless and uptight, and it paints the men as lovable, goofy, fun-loving guys”.] Rogen and Apatow really pushed It was late afternoon in early June 2018—as the sun split through the trees onto the back at the statement, and her career really went south afterwards because of it. Later, Rogen brownstones and street hawkers outside—that Betty Tompkins welcomed Wil and I into her was very casual about having destroyed her career. There we have it, straight from the horse’s Soho studio. Having just returned to New York from her house in Pennsylvania, Tompkins mouth: casual misogyny. shuffled around canvases and books piled high on the hardwood floors as she led us to a congregation of mismatched chairs. It’s interesting to see how blatant the caricaturisation of women is in film and television from even ten years ago. Sex and the City , for example, feels rather un-feminist and non- Born in Washington D.C. in 1945, Tompkins is best known for her Fuck Paintings : intersectional where it once was deemed progressive. One can chart progress of our times monochrome, photorealist images of closely-cropped sexual acts and genitalia which she through the portrayal of women in the media landscape. began in the late 1960s. Pornography is an inexhaustible treasure trove of reference material for those who desire to render the body, and Tompkins, following her graduation from Yes, it has actually really changed how we can see them. -

Betty Tompkins 18.01 > 17.03.2018

[email protected] — WWW.RODOLPHEJANSSEN.COM Betty Tompkins 18.01 > 17.03.2018 Rodolphe Janssen is pleased to announce Betty Tompkin’s forth solo project with the gallery from Jan- uary 18th to March 17th 2018. Betty tompkins began painting large scale, photorealistic airbrush paintings of penetrations and mastur- bations in 1969. Beside the feminist content of her work, her intention from the start was to have two distinct elements which would allow the abstract and the sexual content to coexists equally in the work. She achieved this by cropping the images in such a way that only the explicit sexual parts remain, without heads or other body parts. After some group shows in the early 1970’s, her work remained widely overlooked by the critics and art market due to its subject matter. In 1973, two of her works were held and confiscated by French customs for censorship reasons. In 2003, Tompkins was invited by the New York curator Bob Nickas to take part in the 7th Biennale de Lyon which brought extraordinary attention to her work. After that, the Centre Georges Pompidou ac- quired Fuck Painting #1 (one of the two paintings that had been censored in 1973) for its permanent collection. Since the late 1960’s, Betty Tompkins has been painting her Fuck, Cunt or Kiss Paintings, studying dif- ferent mediums going from airbrush to stamps, graphite powder or fingerprints. She imposes a distance with her explicit subjects, or as she says : « I see something intimate made monumental - we see a visual we don’t usually see in a medium we don’t expect. -

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012 Jan 23)

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012_Jan_23) GUIDE TO THE EXHIBITION Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building October 1, 2011–January 28, 2012 Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design Introduction “Doin’ It in Public” documents a radical and fruitful period of art made by women at the Woman’s Building—a place described by Sondra Hale as “the first independent feminist cultural institution in the world.” The exhibition, two‐volume publication, website, video herstories, timeline, bibliography, performances, and educational programming offer accounts of the collaborations, performances, and courses conceived and conducted at the Woman’s Building (WB) and reflect on the nonprofit organization’s significant impact on the development of art and literature in Los Angeles between 1973 and 1991. The WB was founded in downtown Los Angeles in fall 1973 by artist Judy Chicago, art historian Arlene Raven, and designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville as a public center for women’s culture with art galleries, classrooms, workshops, performance spaces, bookstore, travel agency, and café. At the time, it was described in promotional materials as “a special place where women can learn, work, explore, develop their own point of view and share it with everyone. Women of every age, race, economic group, lifestyle and sexuality are welcome. Women are invited to express themselves freely both verbally and visually to other women and the whole community.” When we first conceived of “Doin’ It in Public,” we wanted to incorporate the principles of feminist art education into our process.