Evidence from the CSI 300 Index Additions and Deletions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinaamc CSI 300 Index ETF (Stock Code: 83188/3188) Fund Factsheet

ChinaAMC CSI 300 Index ETF (Stock Code: 83188/3188) Fund Factsheet As of 29 Apr 2016 37/F, Bank of China Tower, 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong • ChinaAMC CSI 300 Index ETF (the ”Fund”) is a passively managed exchange traded fund and is listed on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “SEHK”), investing primarily and directly in underlying A-Shares of CSI 300 Index through the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (“RQFII”) quota obtained by the Fund’s Manager. • The Fund is subject to single country (the PRC) concentration risk. Investing in emerging markets, such as the PRC, involves a greater risk such as greater political, tax, economic, foreign exchange, liquidity and regulatory risks. • The RQFII policy and rules are new and such policy and rules are subject to change, such changes may have retrospective effect. Repatriations of the invested capital and net profits by RQFIIs are permitted daily and are not subject to any lock-up periods or prior approval. There is no assurance, however, that repatriation restrictions will not be imposed in the future. Any new restrictions on repatriation may impact on the Fund’s ability to meet redemption requests. • There are risks and uncertainties associated with the current PRC tax laws and regulations. The Manager will at present make certain provisions for the Fund in respect of any potential tax liability. In case of any shortfall between the provision and actual tax liabilities, which will be debited from the Fund’s assets, the Fund’s asset value will be adversely affected. • The SEHK’s dual counter model in Hong Kong is new and the Fund is one of the first ETFs to have units traded and settled in RMB and HKD. -

C-Shares CSI 300 Index ETF Prospectus 匯添富資產管理(香 港)有限公司

China Universal International ETF Series C-Shares CSI 300 Index ETF Prospectus 匯添富資產管理(香 港)有限公司 China Universal Asset Management (Hong Kong) Company Limited 2701 One IFC, 1 Harbour View Street, Central, Hong Kong Tel: (852) 3983 5600 Fax: (852) 3983 5799 Email: [email protected] Web: www.99fund.com.hk Important - If you are in any doubt about the contents of this Prospectus, you should consult your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant and/or other financial adviser for independent professional financial advice. CHINA UNIVERSAL INTERNATIONAL ETF SERIES (a Hong Kong umbrella unit trust authorized under Section 104 of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571) of Hong Kong) C-Shares CSI 300 Index ETF (Stock Codes: 83008 (RMB counter) and 03008 (HKD counter)) PROSPECTUS MANAGER China Universal Asset Management (Hong Kong) Company Limited LISTING AGENT FOR C-Shares CSI 300 Index ETF GF Capital (Hong Kong) Limited 3 July 2013 The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (“SEHK”), Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (“HKEx”), Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited (“HKSCC”) and the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (“Commission”) take no responsibility for the contents of this Prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Prospectus. China Universal International ETF Series (“Trust”) and its sub-funds set out in Part 2 of this Prospectus, including its initial Sub-Fund, C-Shares CSI 300 Index ETF (“CSI 300 ETF”) (collectively referred to as the “Sub- Funds”) have been authorised by the Commission pursuant to section 104 of the Securities and Futures Ordinance. -

E FUND CSI 100 A-Share Index ETF

IMPORTANT: The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “SEHK”), Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (“HKEx”), the Securities and Futures Commission (“SFC”) and the Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this Announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Announcement. The Manager accepts full responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained in this Announcement as at the date of publication, and confirms, having made all reasonable enquiries, that to the best of its knowledge and belief, there are no other facts the omission of which would make any statement misleading and opinions expressed in this Announcement have been arrived at after due and careful consideration. SFC authorisation is not a recommendation or endorsement of a scheme nor does it guarantee the commercial merits of a scheme or its performance. It does not mean the scheme is suitable for all investors nor is it an endorsement of its suitability for any particular investor or class of investors. THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. IF IN DOUBT, PLEASE SEEK PROFESSIONAL ADVICE. E FUND CSI 100 A-Share Index ETF RMB Counter Stock Code: 83100 HKD Counter Stock Code: 03100 (Sub-fund of E Fund ETFs Trust (the “Trust”), a Hong Kong umbrella unit trust, authorised under Section 104 of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571 of the laws of Hong Kong SAR)) Announcement Change of Underlying Index and Change of Name and Short Name of the Sub-Fund Dear Unitholders, E Fund Management (Hong Kong) Co., Limited (the “Manager”), the manager of the Trust and the Sub- Fund, hereby announces that, with effect from 7 December 2020 (the “Effective Date”), the underlying index of the Sub-Fund will be changed to CSI 300 Index. -

Chinaamc CSI 300 Index ETF (The "Fund"), Investor Should Refer to the Fund's Prospectus for Details, Including the Risk Factors

Investment involves risks, including the loss of principle. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Before investing in the ChinaAMC CSI 300 Index ETF (the "Fund"), investor should refer to the Fund's prospectus for details, including the risk factors. You should not make investment decision based on the information on this material alone. Please note: • The Fund aims to provide investment result that, before fees and expenses, closely corresponds to the performance of the CSI 300 Index (the "Index"). The Fund invests in the PRC's securities market through the RQFII investment quota granted to the Manager and the Stock Connect. • The Fund is subject to concentration risk as a result of tracking the performance of a single geographical region (the PRC) and may likely be more volatile than a broad-based fund. • The Fund is subject to risks relating to the RQFII regime, such as default in execution or settlement of transaction by a PRC broker or the PRC Custodian, change of RQFII policy and rules and uncertainty to their implementa- tion, repatriation restrictions and insufficient RQFII quota to the Fund. • The Fund is subject to risks associated with the Stock Connect, such as change of relevant rules and regulations, quota limitations, suspension of the Stock Connect programme. In the event that the Fund’s ability to invest in A-Shares through the Stock Connect on a timely basis is adversely affected, the Manager can only rely on RQFII investments to achieve the Fund’s investment objective. • Investing in emerging markets, such as the PRC, involves a greater risk such as greater political, tax, economic, foreign exchange, liquidity and regulatory risks. -

A Sub-Fund of the World Index Shares Etfs (Stock Code : 2827)

W.I.S.E. – CSI 300 China Tracker® * (*This is a synthetic ETF) a sub-fund of the World Index Shares ETFs (stock code : 2827) PROSPECTUS 30 October 2015 IMPORTANT: If you are in doubt about the contents of this Prospectus, you should seek independent professional financial advice. The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (“SEHK”), the Securities and Futures Commission (“SFC”) and the Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this Prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Prospectus. i IMPORTANT INFORMATION FOR INVESTORS Investors should note that an investment in the Sub-Fund is not the same as an investment in the underlying A Shares of the CSI 300 Index. The Sub-Fund primarily invests in A Share through A-Share access products, AXPs, each of which is a derivative instrument linked to an A Share or a basket of A Shares and the value of such AXPs depends entirely on the credit risk of the issuers. Also, as the Manager is a QFII, the Manager will invest directly in the PRC A Shares on behalf of the Sub-Fund to the extent of such portion of the Manager’s QFII investment quota as the Manager may allocate to the Sub-Fund. The Sub-Fund may also invest, and have direct access to, certain eligible A Shares of PRC companies listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange (A Shares that are SSE Securities) via the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect (as defined in “Definition” section on page 9). -

Ishares Core CSI 300 ETF 82846/ As of 31/08/2021 9846

2846/ iShares Core CSI 300 ETF 82846/ As of 31/08/2021 9846 INVESTMENT OBJECTIVE FUND DETAILS The iShares Core CSI 300 Index ETF seeks to track the performance of an index Asset Class Equity composed of 300 large and mid-capitalization stocks traded on the Shanghai and Inception Date 12/11/2009 Shenzhen stock exchanges. Benchmark CSI 300 Index Number of Holdings 301 WHY 2846? Net Assets 244,617,181 CNY Management Fee (in 0.38 1 Exposure to the 300 largest stocks listed on Shanghai and Shenzhen stock %) exchanges Units Outstanding 7,750,000 2 Liquid trading vehicle for the China A-share market Domicile Hong Kong Base Currency RMB GROWTH OF 10,000 CNY SINCE INCEPTION Bloomberg CSIN0300 Benchmark Ticker TOP 10 HOLDINGS (%) KWEICHOW MOUTAI LTD A 4.97 CHINA MERCHANTS BANK LTD A 3.08 PING AN INSURANCE (GROUP) OF CHINA 2.74 WULIANGYE YIBIN LTD A 1.98 LONGI GREEN ENERGY Fund Benchmark TECHNOLOGY LTD 1.97 The chart shows change of investment amount based on a hypothetical investment in MIDEA GROUP LTD A 1.65 the Fund. INDUSTRIAL BANK LTD A 1.36 ANNUALIZED PERFORMANCE (%CNY) EAST MONEY INFORMATION LTD A 1.30 Cumulative Annualized BYD LTD A 1.28 1 Month 3 Month YTD 1 Year 3 Year 5 Year Since HANGZHOU HIKVISION DIGITAL Inception TECHNOL 1.22 Fund 0.09% -8.78% -6.68% 0.97% 14.46% 8.88% 2.83% Total 21.55 Benchmark 0.11% -8.69% -6.41% 1.40% 15.06% 9.64% 4.59% Holdings are subject to change. -

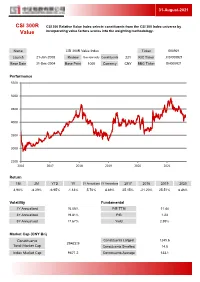

CSI 300R Value Index Ticker 000921

31-August-2021 CSI 300R CSI 300 Relative Value Index selects constituents from the CSI 300 Index universe by Value incorporating value factors scores into the weighting methodology. Name CSI 300R Value Index Ticker 000921 Launch 21-Jan-2008 Review Semiannually Constituents 221 RIC Ticker .CSI000921 Base Date 31-Dec-2004 Base Point 1000 Currency CNY BBG Ticker SH000921 Performance 5500 5000 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Return 1M 3M YTD 1Y 3Y Annualized 5Y Annualized 2017 2018 2019 2020 3.90% -8.29% -6.95% -1.13% 5.70% 4.89% 25.15% -21.20% 25.51% 8.46% Volatility Fundamental 1Y Annualized 16.05% P/E TTM 11.44 3Y Annualized 19.81% P/B 1.23 5Y Annualized 17.67% Yield 2.95% Market Cap (CNY Bn) Constituents Constituents Largest 1245.6 29422.9 Total Market Cap Constituents Smallest 14.8 Index Market Cap 9671.2 Constituents Average 133.1 31-August-2021 Exchange Breakdown Sector Breakdown 2.2% Energy 1.6% 3.8% Materials 7.3% 10.1% Industrials 26.8% Consumer Disc. 13.5% Shanghai Consumer Staples Shenzhen Health Care 11.8% 43.5% Financials 73.2% Information Tech. 4.0% Telecom. Services 2.3% Utilities Top 10 Constituents Ticker Name Sector Exchange Weight 600036 China Merchants Bank Co Ltd Financials Shanghai 6.27% 601318 Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China Ltd Financials Shanghai 5.59% 601166 Industrial Bank Financials Shanghai 2.78% 000333 Midea Group CO., LTD Consumer Disc. Shenzhen 2.52% 600900 China Yangtze Power Co Ltd Utilities Shanghai 2.27% 600030 CITIC Securities Co Ltd Financials Shanghai 2.26% 000651 Gree Electric Appliances,Inc. -

Annual Report DBX ETF Trust

May 31, 2021 Annual Report DBX ETF Trust Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF (ASHR) Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF (ASHS) Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF (CN) Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF (ASHX) DBX ETF Trust Table of Contents Page Shareholder Letter ....................................................................... 1 Management’s Discussion of Fund Performance ............................................. 3 Performance Summary Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF ........................................... 6 Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF .................................. 8 Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF .................................................... 10 Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF ............................................ 12 Fees and Expenses ....................................................................... 14 Schedule of Investments Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF ........................................... 15 Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF .................................. 20 Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF .................................................... 28 Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF ............................................ 33 Statements of Assets and Liabilities ........................................................ 42 Statements of Operations ................................................................. 43 Statements of Changes in Net -

Consumption Upgrade Bolsters Longterm Outlook for a Shares

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Monday, May 6, 2019 | 17 MARKETS Consumption upgrade bolsters Demand from China and India buoys LNG longterm outlook for A shares SHANGHAI — Global natural plan,” Pouyanne said. gas market is undergoing substan The IEA predicted that from tial changes as demand from 2017 to 2023, China alone would emerging economies such as Chi account for a third of global gas Makers of Chinese na and India is increasing at a rap demand growth, thanks in part to id pace, according to industry the country’s “Blue Skies” policy liquor, appliances, observers. and the strong drive to improve air foods, beverages At the 19th International Con quality. ference and Exhibition on Lique In 2018, China’s natural gas con and interior decor fied Natural Gas in Shanghai sumption totaled 280.3 billion earlier this month, industry cubic meters, a robust growth of 18 to benefit big time experts said rising LNG supply percent from a year ago. Driven by and growing demand are injecting the growing gas consumption, Chi By SHI JING in Shanghai dynamism into the market. na imported 90 million metric tons [email protected] The LNG conference, first held of natural gas in 2018, a yearon in 1968, is a triennial industry year growth of almost 32 percent. Investors holding a long position in event. This year marks the first The growth rate was higher than stocks of consumptionrelated com time that the conference was held the 27percent increase in 2017. panies in China’s Ashare market will in China, the world’s fastestgrow “Global LNG industry is under likely reap rich dividends over the ing LNG market. -

Are Tightened Trading Rules Always Bad? Evidence from the Chinese Index Futures Market

Are Tightened Trading Rules Always Bad? Evidence from the Chinese Index Futures Market Hai Lin Victoria University of Wellington You Wang Xiamen University ∗ Friday 20th January, 2017 ∗Correspondence: Hai Lin, School of Economics and Finance, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington 6140, New Zealand. Phone: (+64)- 4- 463- 5239 and email: [email protected]. You Wang, Department of Finance, School of Economics, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, China. We thank Toby Daglish and seminar participants at Victoria University of Wellington and Fifth International Conference on Futures and Other Derivatives for very helpful comments. Wang acknowledges the support from China Scholarship Council. Abstract This paper investigates the impact of tightened trading rules on the market efficiency and the price discovery function of Chinese stock index futures in 2015. In contrast with severe criticism of these changes, we fail to find empirical evidence that market efficiency and price discovery de- teriorated after these rule changes. Using variance ratio and spectral shape tests, we find that the Chinese index futures market became even more efficient after the tightened rules came into effect. Furthermore, by employing Schwarz and Szakmary (1994) and Hasbrouck (1995) price discovery measures, we find that the price discovery function, to some extent, became better. This is consis- tent with Stein (2009), who finds that regulations on leverage can be helpful in a bad market state, and Zhu (2014), who finds that price discovery can be improved with reduced liquidity. It also sug- gests that the new rules may effectively regulate the manipulation behaviour of the Chinese stock index futures market, and then positively affect its market efficiency and price discovery function. -

Ishares Core CSI 300 ETF Factsheet

2846/ iShares Core CSI 300 ETF 82846/ As of 31/08/2021 9846 IMPORTANT: Investment involves risk, including the loss of principal. Investors should refer to the Prospectus and Key Facts Statement of the iShares Core CSI 300 Index ETF (the “ETF”) for details, including the risk factors. Investors should not base investment decisions on this marketing material alone. Investors should note: • The ETF aims to provide investment results that, before fees and expenses, closely correspond to the performance of CSI 300 Index (the “Underlying Index”). • Generally, investments in emerging markets, such as the A Share market, may involve increased risks such as liquidity risks, currency risks/control, political and economic uncertainties, legal, regulatory and taxation risks, settlement risks, custody risk and the likelihood of a high degree of volatility. The A Share market may be more volatile and unstable than those in the more developed markets. The ETF’s exposure is concentrated in the PRC and may be more volatile than funds adopting a more diversified strategy. • The ETF currently does not provision for withholding tax on capital gains (“CGT”) arising from its investment via RQFII or its investment via Stock Connect. There are risks and uncertainties associated with the current PRC tax laws, regulations and practice in respect of capital gains realized on the ETF’s PRC investments, which may have retrospective effect. Any increased tax liabilities on the ETF may adversely affect its value, and the resultant tax liability would be eventually borne by investors. • The ETF is subject to restrictions and requirements applicable to RQFII investment, and the applicable laws, rules and regulations in the PRC, which are subject to change and such change may have potential retrospective effect. -

Semi-Annual Report DBX ETF Trust

November 30, 2020 Semi-Annual Report DBX ETF Trust Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF (ASHR) Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF (ASHS) Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF (CN) Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF (ASHX) DBX ETF Trust Table of Contents Page Shareholder Letter ....................................................................... 1 Portfolio Summary Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF ........................................... 3 Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF .................................. 4 Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF .................................................... 5 Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF ............................................ 6 Fees and Expenses ....................................................................... 7 Schedule of Investments Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF ........................................... 8 Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF .................................. 13 Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF .................................................... 21 Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF ............................................ 26 Statements of Assets and Liabilities ........................................................ 34 Statements of Operations ................................................................. 35 Statements of Changes in Net Assets ....................................................... 36 Financial Highlights