Joint T-RFMO Bycatch Working Group Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MATTHEW EBDEN AUS @Mattebden @Mattebdentennis @Matt Ebden

MATTHEW EBDEN AUS @mattebden @mattebdentennis @matt_ebden BORN: 26 November 1987, Durban, South Africa HEIGHT / WEIGHT: 1.88m (6'2") / 80kg (176lbs) RESIDENCE: Perth, Australia PLAYS: Right-handed · Two-handed backhand CAREER W-L: 68-106 CAREER PRIZE MONEY: $2,932,255 CAREER W-L VS. TOP 10: 3-9 HIGHEST ATP RANKING: 39 (22 October 2018) CAREER 5TH-SET RECORD: 2-3 HIGHEST ATP DOUBLES RANKING: 57 (25 June 2012) 2018 HIGHLIGHTS CAREER FINALIST (1): 2017 (1): Newport > Idols growing up were Stefan PRIZE MONEY: $961,714 (G). Edberg and Andre Agassi. W-L: 19-22 (singles), 10-16 (doubles) CAREER DOUBLES TITLES (4). FINALIST (1). > Hobbies are going to the beach, SINGLES SF (2): ’s-Hertogenbosch, surfing, movies and computer Atlanta PERSONAL games. Enjoys collecting QF (3): Halle, Chengdu, Shanghai > Began playing tennis at age 5 watches and studying with his family in South Africa. horology. CAREER HIGHLIGHTS > Moved to Australia at age 12. > If he wasn't a tennis player, he > Achieved career-high No. 39 on > Went to high school at would probably be a lawyer. 22 October 2018 following prestigious Hale School in > Enrolled at University of personal-best 19th win of Perth. Western Australia to pursue a season. Broke into Top 50 on 16 > Father, Charles, is a chief law/commerce degree, but July 2018 after reaching financial officer and played deferred to play pro tennis. Wimbledon 3R. Rose 600+ spots state cricket and tennis in > Favourite sports team is the from No. 695 to No. 76 in 2017. South Africa; mother, Ann, is a Wallabies (Rugby Union). -

Federal Register/Vol. 83, No. 114/Wednesday, June 13, 2018

27652 Federal Register / Vol. 83, No. 114 / Wednesday, June 13, 2018 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE COMPLAINT seeds with new genetically modified The United States of America, acting traits, as well as other innovative Antitrust Division under the direction of the Attorney products that improve yields for farmers. This competition is central to United States of America v. Bayer AG General of the United States, brings this civil antitrust action to prevent Bayer their businesses. Monsanto’s chief and Monsanto Company; Proposed technology officer has said that Final Judgment and Competitive AG from acquiring Monsanto Company. The United States alleges as follows: innovation is ‘‘the heart and soul of who Impact Statement we are.’’ Similarly, Bayer’s core strategy I. INTRODUCTION is to become the ‘‘most innovative’’ Notice is hereby given pursuant to the agricultural company in the world. Both Antitrust Procedures and Penalties Act, 1. Bayer’s proposed $66 billion acquisition of its rival, Monsanto, would companies invest significant sums of 15 U.S.C. § 16(b)–(h), that a proposed money into research and development Final Judgment, Stipulation and Order, combine two of the largest agricultural companies in the world. Across the and monitor each other’s efforts, and Competitive Impact Statement have spurring each other to work faster and been filed with the United States globe, Bayer and Monsanto compete to sell seeds and chemicals that farmers invest more to improve their offerings District Court for the District of and develop new products. For Columbia in United States of America v. use to grow their crops. This competition has bolstered an American instance, Monsanto recently developed Bayer AG and Monsanto Company, a seed treatment product that protects Civil Action No. -

Tuesday First-Round Matches

CORDOBA OPEN – ATP MEDIA NOTES DAY 2 – TUESDAY 4 FEBRUARY 2020 Kempes Stadium | Cordoba, Argentina | 3-9 February 2020 ATP Tour Tournament Media ATPTour.com cordobaopen.com Edward La Cava: [email protected] (ATP PR) Twitter: @ATPTour @CordobaOpen Lucia Rodriguez Bosch: [email protected] (Press Officer) Facebook: @ATPTour @cordobaopen TV & Radio: TennisTV.com FEDEX ATP HEAD 2 HEADS: TUESDAY FIRST-ROUND MATCHES CANCHA CENTRAL [Q] Facundo Bagnis (ARG) vs [5] Albert Ramos-Vinolas (ESP) Ramos-Vinolas Leads 1-0 19 Sao Paulo (Brazil) Clay R32 Albert Ramos-Vinolas 6-1 6-3 Other Meetings 09 Meknes Q (Morocco) Clay Q3 Albert Ramos-Vinolas 6-2 6-2 10 Asuncion CH (Paraguay) Clay R32 Albert Ramos-Vinolas 6-3 6-1 Bagnis Summary | Age: 28 | World No. 135 | 0-0 in 2020 | 0-1 at Cordoba (2019 1R) • In 2020, has 2-2 record on ATP Challenger Tour with 2R (after 1R bye) in Noumea, New Caledonia and QF last week in Punta del Este, URU (l. to A. Martin). • Also lost in 2R qualifying at Australian Open (d. Napolitano, l. to lla Martinez). • In 2019, qualified 4 times on ATP Tour and lost in 1R each time, in Cordoba (l. to Cuevas), Buenos Aires (l. to Marterer), Sao Paulo (l. to Ramos-Vinolas) and Marrakech (l. to Munar). Reached QF in Umag (d. Klizan, Serdarusic, l. to Caruso) as direct entry. • In Challengers, reached final in Braga, POR (l. to Domingues), Lisbon (l. to Carballes Baena) and Buenos Aires (l. to Nagal) along with SF in Punte del Este (l. -

ECPR General Conference

13th General Conference University of Wrocław, 4 – 7 September 2019 Contents Welcome from the local organisers ........................................................................................ 2 Mayor’s welcome ..................................................................................................................... 3 Welcome from the Academic Convenors ............................................................................ 4 The European Consortium for Political Research ................................................................... 5 ECPR governance ..................................................................................................................... 6 Executive Committee ................................................................................................................ 7 ECPR Council .............................................................................................................................. 7 University of Wrocław ............................................................................................................... 8 Out and about in the city ......................................................................................................... 9 European Political Science Prize ............................................................................................ 10 Hedley Bull Prize in International Relations ............................................................................ 10 Plenary Lecture ....................................................................................................................... -

49,80 % 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Querrrey-Londero 1 1,20 1:3 KO NE 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Čepelová-Hsieh S.W

Datum Místo konání události Zápas Tip Kurs Výsl. Stav FREE TIPY 17.08.2019 ATP WINSTOM SALEM (Q) Chrysosos - Peliwo 1 2,11 2:0 OK ANO Úspěšnost 65,80 % 17.08.2019 CORDENONS (SF) Eriksson-Jahn 2 1,44 0:2 OK ANO 17.08.2019 ITK KOKSIJDE (SF) Soderlung-Geens 1 1,37 2:0 OK ANO Podaných tipů: Vyhraných: 18.08.2019 ITK KOKSIJDE (F) Onclin-Soderlung 2 1,41 0:2 OK ANO Prohraných: Nevyhodnocených 18.08.2019 CORDENONS (F) Jahn-O´Connell 1 1,64 0:2 KO ANO 19.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Molleker-Torpegaard 2 1,54 0:2 OK ANO 367 0 19.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Nadna-Otte 2 1,35 0:2 OK ANO 19.08.2019 L´AAQUILLA CHALL. (2K) Seyboth Wild-Belluci 1 1,39 2:0 OK ANO 1073 20.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Vatutin-Couacaud 2 1,36 0:2 OK ANO 20.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Caruso-Chung 1 1,39 2:0 OK ANO 706 21.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Kavčič-Uchiyama 2 1,61 0:2 OK ANO 21.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Kwon Soon Woo-Otte 1 1,23 2:0 OK ANO 21.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Torpegaard-Galan D. 1 1,46 1:2 KO ANO 21.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Barrere-Milojevic 1 1,53 2:1 OK ANO 22.08.2019 ITF POZNAŇ (2R) Mridha-Sakamoto 1 3,25 2:0 OK NE 22.08.2019 ITF POZNAŇ (2R) Vellotti-Oliveiri 1 1,63 2:1 OK NE 22.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Caruso-Rosol 1 1,45 0:2 KO NE 22.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Bemmelmans-Ivashka 2 1,38 0:2 OK NE 23.08.2019 ITF SANTANDER (QF) Luz-Nikles 1 1,30 2:1 OK NE 23.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Koepfer-Uchiyama 1 1,49 2:0 OK NE 24.08.2019 ITF SCHLIEREN (SF) Ehrat-Bonzi 1 1,50 1:2 KO NE Úspěšnost KLIENTU (Jejich tiketů) 25.08.2019 ITF HELSINKI (SF) Cerundolo-Salminen 1 1,50 2:0 OK NE 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Corič-Donskoy 1 1,24 3:0 OK NE 49,80 % 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Querrrey-Londero 1 1,20 1:3 KO NE 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Čepelová-Hsieh S.W. -

![[Click Here and Type in Recipient's Full Name]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0661/click-here-and-type-in-recipients-full-name-1930661.webp)

[Click Here and Type in Recipient's Full Name]

MEDIA NOTES City ATP Tour PR Tennis Australia PR Sydney Brendan Gilson: [email protected] Harriet Rendle: [email protected] Brisbane Richard Evans: [email protected] Kirsten Lonsdale: [email protected] Perth Mark Epps: [email protected] Victoria Bush: [email protected] ATPCup.com, @ATPCup / ATPTour.com, @ATPTour / TennisTV.com, @TennisTV ATP CUP TALKING POINTS - SATURDAY 4 JANUARY 2020 • World No. 1 Rafael Nadal (ESP), No. 2 Novak Djokovic (SRB) and No. 4 Dominic Thiem (AUT) make their ATP Cup debuts Saturday as the second match of the night session in Perth, Brisbane and Sydney respectively. • Thiem takes on Borna Coric (CRO) at Ken Rosewall Arena in Sydney. Though Thiem has yet to break into the Top 3 of the FedEx ATP Rankings, he has at least four wins over Nadal, Djokovic and No. 3 Roger Federer. o 4-9 vs Nadal Wins at 2016 Buenos Aires, 2017 Rome, 2018 Madrid and 2019 Barcelona o 4-6 vs Djokovic Wins at 2017 & 2019 Roland Garros, 2018 Monte-Carlo and 2019 Nitto ATP Finals o 5-2 vs Federer Wins at Rome & Stuttgart in 2016 and Indian Wells, Madrid & ATP Finals in 2019 • Only three other players have at least four wins over each member of the Big Three -- 34-year-old Jo-Wilfried Tsonga, 32-year-old Andy Murray and 31-year-old Juan Martin del Potro. Thiem is 26 years old and his .433- win percentage against the Big Three is better than Murray’s (.341), Tsonga’s (.291) and Del Potro’s (.274). -

IESE Cities in Motion Index

IESE Cities in Motion Index 2019 IESE Cities in Motion Index 2019 We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) of the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness—ECO2016-79894-R (MINECO/FEDER), the Schneider-Electric Sustainability and Business Strategy Chair, the Carl Schroeder Chair in Strategic Management and the IESE’s High Impact Projects initiative (2017/2018). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15581/018.ST-509 CONTENTS Foreword 07 About Us 09 Working Team 09 Introduction: The Need for a Global Vision 10 Our Model: Cities in Motion. Conceptual Framework, Definitions and Indicators 11 Limitations of the Indicators 23 Geographic Coverage 23 Cities in Motion: Ranking 25 Cities in Motion: Ranking by Dimension 28 Cities in Motion: Regional Ranking 40 Noteworthy Cases 46 Evolution of the Cities in Motion Index 50 Cities in Motion Compared With Other Indexes 53 Cities in Motion: City Ranking by Population 54 Cities in Motion: Analysis of Dimensions in Pairs 57 Cities in Motion: A Dynamic Analysis 64 Recommendations and Conclusions 66 Appendix 1. Indicators 69 Appendix 2. Graphical Analysis of the Profiles of the 174 Cities 76 Foreword Once again, we are pleased to present a new edition (the sixth) of our IESE Cities in Motion Index (CIMI). Over the past years, we have observed how various cities, companies and other social actors have used our study as a benchmark when it comes to understanding the reality of cities through comparative analysis. As in every edition, we have tried to improve the structure and coverage of the CIMI and this, the sixth edition, has been no exception. -

Cordoba Open Singles Country

CORDOBA OPEN – ATP MEDIA NOTES PREVIEW & DAY 1 – MONDAY 3 FEBRUARY 2020 Kempes Stadium | Cordoba, Argentina | 3-9 February 2020 ATP Tour Tournament Media ATPTour.com cordobaopen.com Edward La Cava: [email protected] (ATP PR) Twitter: @ATPTour @CordobaOpen Lucia Rodriguez Bosch: [email protected] (Press Officer) Facebook: @ATPTour @cordobaopen TV & Radio: TennisTV.com CORDOBA OPEN SINGLES SEED PLAYER 2019 W-L (BEST FINISH) CORDOBA W-L (BEST FINISH) 1 Diego Schwartzman (ARG) 40-26 (Los Cabos Champion) 1-1 (2019 QF) 2 Guido Pella (ARG) 36-25 (Sao Paulo Champion) 4-1 (2019 Finalist) 3 Cristian Garin (CHI) 32-24 (Munich, Houston Champion) 0-0 (Debut) 4 Laslo Djere (SRB) 20-22 (Rio de Janeiro Champion) 0-0 (Debut) 5 Albert Ramos-Vinolas (ESP) 30-24 (Gstaad Champion) 1-1 (2019 2R) 6 Pablo Cuevas (URU) 24-23 (Estoril Finalist) 3-1 (2019 SF) 7 Fernando Verdasco (ESP) 26-27 (4 QFs) 0-0 (Debut) 8 Juan Ignacio Londero (ARG) 22-21 (Cordoba Champion) 5-0 (2019 Champion) Singles Final Sunday 9 February not before 7:00 p.m. Qualifiers (4) Facundo Bagnis (ARG), Juan Pablo Ficovich (ARG), Pedro Martinez (ESP), Carlos Taberner (ESP) Wild Cards (3) Pedro Cachin (ARG), Francisco Cerundolo (ARG), Cristian Garin (CHI) #NextGenATP (1) Corentin Moutet (20) Oldest Player Fernando Verdasco (36) COUNTRY BREAKDOWN (11) Argentina (10) Facundo Bagnis, Pedro Cachin, Francisco Cerundolo, Federico Coria, Federico Delbonis, Juan Pablo Ficovich, Juan Ignacio Londero, Leonardo Mayer, Guido Pella, Diego Schwartzman Spain (7) Pablo Andujar, Roberto Carballes -

52,98 % 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Čepelová-Hsieh S.W

Datum Místo konání události Zápas Tip Kurs Výsl. Stav FREE TIPY 17.08.2019 ATP WINSTOM SALEM (Q) Chrysosos - Peliwo 1 2,11 2:0 OK ANO 17.08.2019 CORDENONS (SF) Eriksson-Jahn 2 1,44 0:2 OK ANO Úspěšnost 67,56 % 17.08.2019 ITK KOKSIJDE (SF) Soderlung-Geens 1 1,37 2:0 OK ANO Podaných tipů: Vyhraných: 18.08.2019 ITK KOKSIJDE (F) Onclin-Soderlung 2 1,41 0:2 OK ANO Prohraných: Nevyhodnocených 18.08.2019 CORDENONS (F) Jahn-O´Connell 1 1,64 0:2 KO ANO 19.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Molleker-Torpegaard 2 1,54 0:2 OK ANO 0 19.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Nadna-Otte 2 1,35 0:2 OK ANO 231 19.08.2019 L´AAQUILLA CHALL. (2K) Seyboth Wild-Belluci 1 1,39 2:0 OK ANO 20.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Vatutin-Couacaud 2 1,36 0:2 OK ANO 712 20.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Caruso-Chung 1 1,39 2:0 OK ANO 21.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Kavčič-Uchiyama 2 1,61 0:2 OK ANO 481 21.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Kwon Soon Woo-Otte 1 1,23 2:0 OK ANO 21.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Torpegaard-Galan D. 1 1,46 1:2 KO ANO 21.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Barrere-Milojevic 1 1,53 2:1 OK ANO 22.08.2019 ITF POZNAŇ (2R) Mridha-Sakamoto 1 3,25 2:0 OK NE 22.08.2019 ITF POZNAŇ (2R) Vellotti-Oliveiri 1 1,63 2:1 OK NE 22.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Caruso-Rosol 1 1,45 0:2 KO NE 22.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Bemmelmans-Ivashka 2 1,38 0:2 OK NE 23.08.2019 ITF SANTANDER (QF) Luz-Nikles 1 1,30 2:1 OK NE 23.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (Q) Koepfer-Uchiyama 1 1,49 2:0 OK NE 24.08.2019 ITF SCHLIEREN (SF) Ehrat-Bonzi 1 1,50 1:2 KO NE Úspěšnost KLIENTU (Jejich tiketů) 25.08.2019 ITF HELSINKI (SF) Cerundolo-Salminen 1 1,50 2:0 OK NE 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Corič-Donskoy 1 1,24 3:0 OK NE 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Querrrey-Londero 1 1,20 1:3 KO NE 52,98 % 26.08.2019 US OPEN N.YORK (1R) Čepelová-Hsieh S.W. -

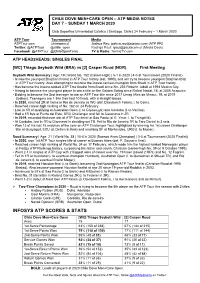

Infosys Atp Scores & Stats

CHILE DOVE MEN+CARE OPEN – ATP MEDIA NOTES DAY 7 – SUNDAY 1 MARCH 2020 Club Deportivo Universidad Catolica | Santiago, Chile | 24 February – 1 March 2020 ATP Tour Tournament Media ATPTour.com chileopen.cl Joshua Rey: [email protected] (ATP PR) Twitter: @ATPTour @chile_open Rodrigo Paut: [email protected] (Media Desk) Facebook: @ATPTour @ChileOpenTenis TV & Radio: TennisTV.com ATP HEAD2HEADS: SINGLES FINAL [WC] Thiago Seyboth Wild (BRA) vs [2] Casper Ruud (NOR) First Meeting Seyboth Wild Summary | Age: 19 | World No. 182 (Career-High) | 5-1 in 2020 | 4-0 at Tournament (2020 Finalist) • Is now the youngest Brazilian finalist in ATP Tour history (est. 1990), and will try to become youngest Brazilian titlist in ATP Tour history. Also attempting to become the lowest-ranked champion from Brazil in ATP Tour history. • Has become the lowest-ranked ATP Tour finalist from Brazil since No. 255 Roberto Jabali at 1994 Mexico City. • Aiming to become the youngest player to win a title on the Golden Swing since Rafael Nadal, 18, at 2005 Acapulco. • Bidding to become the 2nd teenager to win an ATP Tour title since 2017 Umag (Alex de Minaur, 19, at 2019 Sydney). Teenagers are 1-9 in their last 10 finals, with 6 straight losses. • In 2020, reached 2R at home in Rio de Janeiro as WC (def. Davidovich Fokina, l. to Coric). • Reached career-high ranking of No. 182 on 24 February. • Lost in 1R of qualifying at Australian Open (l. to Gojowczyk) and Cordoba (l. to Varillas). • Had a 1R bye at Punta del Este, URU Challenger and fell to Casanova in 2R. -

Abstracts of the 11Th Arab Congress of Plant Protection

Under the Patronage of His Royal Highness Prince El Hassan Bin Talal, Jordan Arab Journal of Plant Protection Volume 32, Special Issue, November 2014 Abstracts Book 11th Arab Congress of Plant Protection Organized by Arab Society for Plant Protection and Faculty of Agricultural Technology – Al Balqa AppliedUniversity Meridien Amman Hotel, Amman Jordan 13-9 November, 2014 Edited by Hazem S Hasan, Ahmad Katbeh, Mohmmad Al Alawi, Ibrahim Al-Jboory, Barakat Abu Irmaileh, Safa’a Kumari, Khaled Makkouk, Bassam Bayaa Organizing Committee of the 11th Arab Congress of Plant Protection Samih Abubaker Chairman Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Al Balqa AppliedApplied University, Al Salt, Jordan Hazem S. Hasan Secretary Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Al Balqa AppliedUniversity, Al Salt, Jordan Ali Ebed Allah khresat Treasurer General Secretary, Al Balqa AppliedUniversity, Al Salt, Jordan Mazen Ateyyat Member Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Al Balqa AppliedUniversity, Al Salt, Jordan Ahmad Katbeh Member Faculty of Agriculture, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan Ibrahim Al-Jboory Member Faculty of Agriculture, Bagdad University, Iraq Barakat Abu Irmaileh Member Faculty of Agriculture, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan Mohmmad Al Alawi Member Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Al Balqa AppliedUniversity, Al Salt, Jordan Mustafa Meqdadi Member Agricultural Materials Company (MIQDADI), Amman Jordan Scientific Committee of the 11th Arab Congress of Plant Protection • Mohmmad Al Alawi, Al Balqa Applied University, Al Salt, Jordan, President -

Lima Group: the Crisis in Venezuela Background Guide Table of Contents

Lima Group: The Crisis In Venezuela Background Guide Table of Contents Letters from Committee Staffers Committee Logistics Introduction to the Committee Introduction to Topic One History of the Problem Past Actions Taken Closing Thoughts Questions to Consider Introduction to Topic Two History of the Problem Past Actions Taken Closing Thoughts Questions to Consider Resources to Use Bibliography Staff of the Committee Chair CeCe Szkutak Vice Chair Erica MacDonald Crisis Director Andrea Gomez Assistant Crisis Director Sophia Alvarado Coordinating Crisis Director: Julia Mullert Under Secretary General Elena Bernstein Taylor Cowser, Secretary General Neha Iyer, Director General Letter from the Chair Hello Delegates! I am so pleased to welcome you to the Lima Group! My name is CeCe Szkutak and I will be your honorable chair for BosMUN XIX. A little about me, I am currently a sophomore at Boston University studying Political Science and Urban Studies. I am originally from Northern Virginia but went to high school in Southern Vermont. I love to ski and have been a ski instructor for the past five winters. I am a sucker for show tunes and absolutely love a good podcast. I participated in Model UN all four years of high school and actually attended BosMUN three times over the years! BosMUN holds a very special place in my heart so I could not be more excited to be chairing this committee. If you have any questions about the structure of the committee or on the topic areas please do not hesitate to reach out. I will make sure to respond in a timely manner and please no question is a dumb question! I’m also happy to answer questions you may have about Boston University or about Model UN at in college.