Hutchings, RM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Victoria Public Library Board Regular Meeting April 23, 2019 12:00P.M

GREATER VICTORIA PUBLIC LIBRARY Greater Victoria Public Library Board Regular Meeting April 23, 2019 12:00p.m. – 1:00p.m. Central Branch Community Meeting Room 735 Broughton Street Victoria BC Regular meeting of the Greater Victoria GREATER VICTORIA Public Library Board PUBLIC LIBRARY April 23, 2019 The GVPL Board recognizes and acknowledges the traditional territory of the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations on which the Central Branch is located and Board Meetings take place. Mission Statement We build community and support literacy and lifelong learning by providing free access to information, space, tools and expertise. Regular meeting of the Greater Victoria GREATER VICTORIA Public Library Board PUBLIC LIBRARY April 23, 2019 1. Call to Order 2. Indigenous Acknowledgement 3. Chair’s Remarks 4. Consent Agenda Motion to Approve 4.1 Approval of Agenda 4.2 Approval of Minutes – March 26, 2019 – Attachment 4.2 5. Officers' Reports 5.1 Chair Report For Information 5.2 CEO Report - Attachment 5.2 For Information 6. Business Arising from Previous Meeting 7. New Business 7.1 Public Libraries Provincial Grants Allocations 2019 – Attachment 7.1 8. Presentations 8.1 Staff Presentation: GVPL Resources and Services for Persons with Disabilities 9. Board Liaison Updates 9.1 Friends of the Library 9.2 GVLRA 9.3 BCLTA 10. In-Camera 11. Next Meeting Date May 28, 2019 12:00pm – 1:00pm 12. Adjournment Attachment 4.2 DRAF T M I N U T E S GREATER VICTORIA PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD REGULAR MEETING Central Branch 735 Broughton Street Community Meeting Room March 26, 2019 12:00p.m. -

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction a Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction A Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada Len Garis, Sarah Hughan, Paul Maxim, and Alex Tyakoff October 2016 Executive Summary Despite the steady reduction in rates of fire that have been witnessed in Canada in recent years, ongoing research has demonstrated that there continue to be striking inequalities in the way in which fire risk is distributed through society. It is well-established that residential dwelling fires are not distributed evenly through society, but that certain sectors in Canada experience disproportionate numbers of incidents. Oftentimes, it is the most vulnerable segments of society who face the greatest risk of fire and can least afford the personal and property damage it incurs. Fire risks are accentuated when property owners or occupiers fail to install and maintain fire and life safety devices such smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors in their homes. These life saving devices are proven to be highly effective, inexpensive to obtain and, in most cases, Canadian fire services will install them for free. A key component of driving down residential fire rates in Canadian cities, towns, hamlets and villages is the identification of communities where fire risk is greatest. Using the internationally recognized Home Safe methodology described in this study, the following Aboriginal and Non- Aboriginal communities in provinces and territories across Canada are determined to be at heightened risk of residential fire. These communities would benefit from a targeted smoke alarm give-away program and public education campaign to reduce the risk of residential fires and ensure the safety and well-being of all Canadian citizens. -

Grant Thornton

. Draft Scenario Analysis Preliminary Draft [Be [.... [ Advice to Cabinet· Not for Public Disclosure Case Selector: l~sec;,paClty 1.... 1 REAL PROVINCIAL REVENUES ($ billions) ' .. :~.... :, 'f. '.:. Royallies .: I PRRT CIT CIT - BC Levy PIT PST s13, s17, s21 PRESENT VALUEs13, s17, s21PROVINCIAL REVENUES ($ bill CIT CIT - BC Levy PIT PST l ~ Page 1 FIN-2014-00006 Key assumptions used in model Australia Tax Case BC Capacity Case Base Capacity High Capacity CIT rate Canadian rate Federal Proportion Federal Rate Provincial Proportion Provincial Rate As provided by Deetken on 7 February 2013 s13, s17, s21 Add: New Levy" BC Tax As provided by Deetken on 7 Febru ary 2013· s13, s17, s21 As provided by Deetken on 7 February 2013 As provided by Deetken on 7 February 2013 Provincial Income Tax Rate s13, s17, s21 Initial s13, s17, s21 PRRT rate BC Treasury (based on Au stralia) PST Assumptions Capex proporlion upon which PST applied As provided by Deetken on 7 February 2013 PST rate As provided by Deetken on 7 February 2013 Employment" PIT income Include? (1 for yes, 2 for no) Operational commencement dates for purposes of BC Tax Base Case High Case Selected Other Assumptions s13, s17, s21 Page 2 FIN-2014-00006 LNG I NG Pricing Assumptions Ikiiiii""''''---- 2011 20 :1 20 3 20 5 20]6 2031 203 Inflatioo Base Year Revenue and cosl blsls: Cosl price Indexation Inllation Index app::ed to Model Revenue price Indexation CBOElEIA indeKaIion (2011 base) World Bank indexation (2012 base Price ForeClilts tmPriee J "''''Btu CooE Forecast Ell. forecast \Volld -

AGENDA GREATER VICTORIA PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD Central Library, 735 Broughton Street Community Meeting Room November 28, 2017 at 12:00 P.M

AGENDA GREATER VICTORIA PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD Central Library, 735 Broughton Street Community Meeting Room November 28, 2017 at 12:00 p.m. The GVPL Board recognizes and acknowledges the traditional territory of the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations on which the Central Branch is located and Board Meetings take place. 1. APPROVAL OF AGENDA Motion to Approve 2. CHAIR’S REMARKS For Information 3. APPROVAL OF MINUTES 3.1 Minutes of the Board Meeting of October 24, 2017 Attachment #3.1 Motion to Approve 4. BUSINESS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MEETING None 5. CEO REPORT TO THE BOARD Attachment #5 For Information 6. COMMITTEE REPORTS 6.1 Planning and Policy Committee Meeting November 7, 2017 Oral Report For Information 6.1.1 Planning and Policy Committee Meeting Minutes June 20, 2017 Attachment #6.1.1 Motion to Approve 6.1.2 Policy #G.3 Board Roles and Structure Attachment #6.1.2 Motion to Approve 6.1.3 Trustee Mentorship Proposal Attachment #6.1.3 Motion to Approve 7. FINANCIAL STATEMENT 7.1 Statement of Financial Activity ending October 31, 2017 Attachment #7.1 Motion to Approve 8. NEW BUSINESS 8.1 2018 Proposed Board Meeting dates Attachment #8.1 Motion to Approve 9. REPORTS / PRESENTATIONS (COMMUNITY & STAFF) 9.1 Staff Presentations For Information • Staff Day 2017/2018 Presentation Attachment # 9.1 Motion to Approve • Truth & Reconciliation Commission Recommendations & GVPL support For Information 9.2 BCLTA Update For Information 9.3 Friends of the Library Update For Information 9.4 IslandLink Federation Update For Information 10. BOARD CORRESPONDENCE 10.1 Letter - Ministry of Education, Libraries Branch Public Library Grants Attachment #10.1 Motion to Receive 10.2 Letter – Name that Library, City of Victoria Attachment #10.2 10.3 Letter – City of Colwood, 2018 Board Appointment Attachment #10.3 12. -

British Columbia Local Area Economic Dependencies: 2006 Author: Garry Horne March 2009

BRITISH COLUMBIA LOCAL AREA ECONOMIC DEPENDENCIES: 2006 AUTHOR: GARRY HORNE MARCH 2009 Funding for this project was made possible through the Labour Market Information initiative under the Canada-British Columbia Labour Market Agreement (LMA), which is administered for BC by the Ministry of Advanced Education and Labour Market Development. British Columbia Local Area Economic Dependencies - 2006 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................1 Abstract.................................................................................................................2 1. Introduction .....................................................................................................3 2. The Descriptive Results for 2006...................................................................4 2.1 Income Dependencies...............................................................................4 2.2 The Diversity of Local Economies ........................................................10 2.3 The Vulnerability of Local Areas to the Forest Sector .......................18 2.4 Tourism.....................................................................................................21 2.5 Location Quotients..................................................................................23 3. The Employment Impact Ratios for 2006...................................................27 -

Diversity Profile of British Columbia, Third Edition

DIVERSITY PROFILE of British Columbia Coordinated by Veenu Saini, Program Director Law Foundation of BC Fourth Edition November 2014 Diversity Profile of British Columbia Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... v I. Population and Population Change in Communities ......................................................................... 1 A. Overview ...................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Reader’s Guide to the Tables ........................................................................................................ 3 Table 1-1. Population of Regional Districts, 2011 Census ....................................................................... 6 Table 1-2. Population of Major Urban Areas, 2011 Census .................................................................... 7 Table 1-3. Population of Communities, 2011 Census .............................................................................. 8 Table 1-4. Communities with a Population of More Than 5,000 ........................................................... -

CMD Group CRM Integration CSV Format Administrator's Reference

CMD Group CRM Integration CSV Format Administrator’s Reference DataLink US CSV Format Administrator’s Reference © 2014 Reed Construction Data Copyright notice and statement © 2014 Reed Construction Data® All rights reserved. No part of this document may be copied, photocopied, reproduced, or distributed in any form or by any means without permission in writing from Reed Construction Data, Inc. Notice of liability Information in this document is subject to change without notice. Any software described in this document is furnished under a license agreement and may be used or copied only in accordance with the terms of the agreement. CMD 30 Technology Parkway South Suite 100 Norcross, GA 30092 Publication information Use the following information when referencing this document: Document name: CMD Group CRM Integration CSV Format Administrator’s Reference Publication Date: August 2014 Revision: A CMD Group CRM Integration CSV Format Administrator’s Reference 2 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 4 About this document ................................................................................................................................ 4 Who should use this document ................................................................................................................ 4 File name, location and access .............................................................................................................. -

Standard Geographical Classification (SGC) 2011 Volume I the Classification 2011 How to Obtain More Information

Catalogue no. 12-571-X Standard Geographical Classification (SGC) 2011 Volume I The Classification 2011 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website at www.statcan.gc.ca, e-mail us at [email protected], or telephone us, Monday to Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following numbers: Statistics Canada’s National Contact Centre Toll-free telephone (Canada and United States): Inquiries line 1-800-263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 Fax line 1-877-287-4369 Local or international calls: Inquiries line 1-613-951-8116 Fax line 1-613-951-0581 Depository Services Program Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 Fax line 1-800-565-7757 To access this product This product, Catalogue no. 12-571-X, is available free in electronic format. To obtain a single issue, visit our website at www.statcan.gc.ca and browse by “Key resource” > “Publications.” Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has developed standards of service that its employees observe. To obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “About us” > “The agency” > “Providing services to Canadians.” Statistics Canada Standards Division Standard Geographical Classification (SGC) 2011 Volume I The Classification 2011 Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada © Minister of Industry, 2011 All rights reserved. -

The Arrival of Tradition: the Influence of the Tradition Concept On

TheArrival of Tradition:The Influence of the Tradition Concept on Missionary-Indigenous Interactions in the Nineteenth-Century Pacific Northwest Coast Haeden Stewart, University of Chicago ABSTRACT Tradition is a paradoxical concept that, on the one hand, defines a set of practices as external or resistant to the dynamics of global modern society but, on the other hand, makes sense of these practices in references to modernity itself. Colonial scholarship has struggled with this paradox, taking the appearance of tradition as situated outside modernity at face value. By historicizing the logical form of the con- cept of tradition, this article offers a critique of its use in colonial scholarship. Exam- ining the Oblate missionization of British Columbia in the nineteenth century as a case study, this article tracks how the logical form of tradition was articulated with the development of capital, how it defined Oblate ideology, how it was adopted by various Indigenous communities to make sense of their own social transformation in relation to broader global transformations, and ultimately how it was adopted as a critical analytic by colonial scholars. n 1862 the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (Oblates), a French Catholic missionary order, established a mission at the isthmus of Sechelt, organized in I 1 the manner of the Jesuit reducciones in seventeenth-century Paraguay. The mis- sion was to be a self-sufficient oasis, separate from outside influence. However, I would like to thank Moishe Postone, whose generosity, support, and suggestions were indispensible in the writing of this article. In addition, I would like to thank the reviewers as well as Andrew Sartori for their comments, which greatly improved the article. -

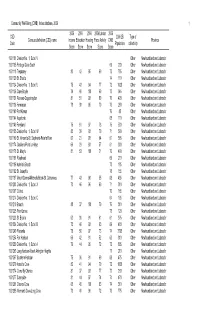

Community Well-Being (CWB) Index Database, 2006 1 CSD Code

Community Well-Being (CWB) Index database, 2006 1 2006 2006 2006 2006 Labour 2006 CSD 2006 2B Type of Census subdivision (CSD) name Income Education Housing Force Activity CWB Province Code Population collectivity Score Score Score Score Score 1001101 Division No. 1, Subd. V Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001105 Portugal Cove South 69 230 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001113 Trepassey 80 42 95 69 72 755 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001120 St. Shott's 74 110 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001124 Division No. 1, Subd. U 75 43 94 77 72 1620 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001126 Cape Broyle 74 49 100 69 73 545 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001131 Renews-Cappahayden 81 51 93 80 76 420 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001136 Fermeuse 78 38 95 70 70 250 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001140 Port Kirwan 76 85 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001144 Aquaforte 68 110 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001149 Ferryland 75 51 97 78 75 530 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001155 Division No. 1, Subd. W 83 39 93 70 71 560 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001169 St. Vincent's-St. Stephen's-Peter's River 67 21 93 64 61 365 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001174 Gaskiers-Point La Haye 66 29 93 57 61 300 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001178 St. Mary's 81 53 100 71 76 460 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001181 Riverhead 69 210 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001186 Admirals Beach 73 185 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001192 St. Joseph's 78 155 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001197 Mount Carmel-Mitchells Brook-St. -

Extra Appendix 2: Reserve-Level Data for the Bottom-Up Approach

Extra Appendix 2: Reserve-Level Data for the Bottom-Up Approach Note: The reserve GDP per capita estimates in this Appendix are developed using the national share of earnings in GDP from the top-down approach (0.473). This is almost identical to the national share of earnings in GDP based on the provincial-level bottom-up approach data (0.481) used in the paper. Appendix Table 7A: Reserve-specific Population, Employment, Earnings and Gross Domestic Product for Newfoundland and Labrador Band Total Registered Employment Employment Average 2005 Total 2005 2005 GDP 2005 GDP per Population Registered Population Aboriginal in 2005 Rate earnings - earnings of On Estimates Capita Estimates (Community- Population on a Reserve identity (Aboriginal (Aboriginal Total Reserve (2005 dollars) (2005 dollars) reported data (Registered (Registered population identity identity Aboriginal Aboriginal (11)= (12)=(11)/(5) Aboriginal in 2006) Population Population as On-Reserve 15 years population 15 population 15 identity identity (10)/0.473 Band(s) on identity Row (1) as of June, of June, Population and over in years and years and population 15 population† 15 Reserve Reserve population No. 2009) 2009) in 2006 2006 over with over) (%) years and years and over in 2006 (2) (3) (4) Census earnings in (8) over with (2005 dollars) (5) Reference 2005) employment (10) = (9)*(7) week (7) income (6) (2005 dollars) (9) Miawpukek Samiajij 1 2,245 2,746 816 867 775 580 480 82.8 15,313 7,350,240 15,544,254 20,057 Miawpukek Mushuau Innu 2 488 713 663 Natuashish 2 706 660 -

Public Libraries Provincial Grant Allocations 2021 Ministry of Municipal Affairs

Public Libraries Provincial Grants Allocations 2021 Grants Public Libraries Branch Ministry of Municipal Affairs June 11, 2021 Public Libraries Provincial Grant Allocations 2021 Ministry of Municipal Affairs Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Public Libraries Provincial Grants Allocations ............................................................................................. 4 Table 1: 2021 Total Provincial Grants Summary ..................................................................................... 4 Table 2: 2021 Grant Amounts by Public Library ...................................................................................... 5 Per Capita Operating Grant ...................................................................................................................... 8 Table 3: 2021 Library Per Capita Operating Grants Summary ............................................................ 9 Resource Sharing Grant .......................................................................................................................... 12 BC OneCard Grant .................................................................................................................................. 13 Literacy & Equity Grant .......................................................................................................................... 14 Appendix A ................................................................................................................................................