Public Participation in the Production of Public Space in Kuwait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kuwaiti Arabic: a Socio-Phonological Perspective

Durham E-Theses Kuwaiti Arabic: A Socio-Phonological Perspective AL-QENAIE, SHAMLAN,DAWOUD How to cite: AL-QENAIE, SHAMLAN,DAWOUD (2011) Kuwaiti Arabic: A Socio-Phonological Perspective, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/935/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Kuwaiti Arabic: A Socio-Phonological Perspective By Shamlan Dawood Al-Qenaie Thesis submitted to the University of Durham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures 2011 DECLARATION This is to attest that no material from this thesis has been included in any work submitted for examination at this or any other university. i STATEMENT OF COPYRIGHT The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Real Estate Guidance 2017 1 Index

Real Estate Guidance 2017 1 Index Brief on Real Estate Union 4 Executive Summary 6 Investment Properties Segment 8 Freehold Apartments Segment 62 Office Space Segment 67 Retail Space Segment 72 Industrial Segment 74 Appendix 1: Definition of Terms Used in the Report 76 Appendix 2: Methodology of Grading of Investment Properties 78 2 3 BRIEF ON REAL ESTATE UNION Real Estate Association was established in 1990 by a distinguished group headed by late Sheikh Nasser Saud Al-Sabahwho exerted a lot of efforts to establish the Association. Bright visionary objectives were the motives to establishthe Association. The Association works to sustainably fulfil these objectives through institutional mechanisms, whichprovide the essential guidelines and controls. The Association seeks to act as an umbrella gathering the real estateowners and represent their common interests in the business community, overseeing the rights of the real estateprofessionals and further playing a prominent role in developing the real estate sector to be a major and influentialplayer in the economic decision-making in Kuwait. The Association also offers advisory services that improve the real estate market in Kuwait and enhance the safety ofthe real estate investments, which result in increasing the market attractiveness for more investment. The Association considers as a priority keeping the investment interests of its members and increase the membershipbase to include all owners segments of the commercial and investment real estate. This publication is supported by kfas and Wafra real estate 4 Executive Summary Investment Property Segment • For the analysis of the investment properties market, we have covered 162,576 apartments that are spread over 5,695 properties across 19 locations in Kuwait. -

Semantic Innovation and Change in Kuwaiti Arabic: a Study of the Polysemy of Verbs

` Semantic Innovation and Change in Kuwaiti Arabic: A Study of the Polysemy of Verbs Yousuf B. AlBader Thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics April 2015 ABSTRACT This thesis is a socio-historical study of semantic innovation and change of a contemporary dialect spoken in north-eastern Arabia known as Kuwaiti Arabic. I analyse the structure of polysemy of verbs and their uses by native speakers in Kuwait City. I particularly report on qualitative and ethnographic analyses of four motion verbs: dašš ‘enter’, xalla ‘leave’, miša ‘walk’, and i a ‘run’, with the aim of establishing whether and to what extent linguistic and social factors condition and constrain the emergence and development of new senses. The overarching research question is: How do we account for the patterns of polysemy of verbs in Kuwaiti Arabic? Local social gatherings generate more evidence of semantic innovation and change with respect to the key verbs than other kinds of contexts. The results of the semantic analysis indicate that meaning is both contextually and collocationally bound and that a verb’s meaning is activated in different contexts. In order to uncover the more local social meanings of this change, I also report that the use of innovative or well-attested senses relates to the community of practice of the speakers. The qualitative and ethnographic analyses demonstrate a number of differences between friendship communities of practice and familial communities of practice. The groups of people in these communities of practice can be distinguished in terms of their habits of speech, which are conditioned by the situation of use. -

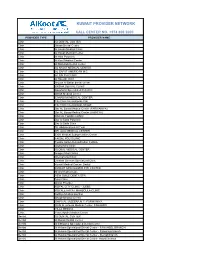

Al Koot Kuwait Provider Network

AlKoot Insurance & Reinsurance Partner Contact Details: Kuwait network providers list Partner name: Globemed Tel: +961 1 518 100 Email: [email protected] Agreement type Provider Name Provider Type Provider Address City Country Partner Al Salam International Hospital Hospital Bnaid Al Gar Kuwait City Kuwait Partner London Hospital Hospital Al Fintas Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Dar Al Shifa Hospital Hospital Hawally Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Hadi Hospital Hospital Jabriya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Orf Hospital Hospital Al Jahra Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Royale Hayat Hospital Hospital Jabriyah Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Alia International Hospital Hospital Mahboula Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Sidra Hospital Hospital Al Reggai Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Rashid Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Seef Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner New Mowasat Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Taiba Hospital Hospital Sabah Al-Salem Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Kuwait Hospital Hospital Sabah Al-Salem Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Medical One Polyclinic Medical Center Al Da'iyah Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Noor Clinic Medical Center Al Ageila Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Quttainah Medical Center Medical Center Al Shaab Al Bahri Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Shaab Medical Center Medical Center Al Shaab Al Bahri Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Saleh Clinic Medical Center Abraq Kheetan Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Global Medical Center Medical Center Benaid Al qar Kuwait City Kuwait Partner New Life -

Kuwait Provider Network

KUWAIT PROVIDER NETWORK CALL CENTER NO. +974 800 2000 PROVIDER TYPE PROVIDER NAME Clinic 32 DENTAL CENTER Clinic Aknan Dental Center Clinic Al Ansari Medical Clinic Clinic Al Hayat Medical Center Clinic Al Hilal Polyclinic Clinic Al Kout Medical Center Clinic Al Muhallab Dental Center Clinic AL NAJAT MEDICAL CENTER Clinic AL SAFAT AMERICAN M.C. Clinic AL SALEH CLINIC Clinic Al Sayegh Clinic Clinic Arouss Al Bahar dental center Clinic BASMA DENTAL CLINIC Clinic Boushahri Specialized Polyclinic Clinic British Medical Center Clinic CANADIAN MEDICAL CENTER Clinic City Clinic International- Fah Clinic City Clinic International- Mirgab Clinic Dar AL Baraa Medical Center (FARWANIYA) Clinic Dar AL Baraa Medical Center (JABRIYA) Clinic DAR AL FOUAD CLINIC Clinic Dar Al Saha Polyclinic Clinic Dar Al Shifa Clinic Clinic Dr. Abdulmohsen Al Terki Clinic DR. ALIA MEDICAL CENTER Clinic EXIR Medical Subspecialties Center Clinic FAISAL POLYCLINIC Clinic Fawzia Sultan Rehabilitation Institute Clinic Global Med Clinic Clinic GLOBAL MEDICAL CENTER Clinic Images Med Clinics Clinic International Clinic Clinic Jarallah German Specialized Clinic Clinic Kuwait Medical Center- Dental Clinic KUWAIT SPECIALIZED EYE CENTER Clinic Metro Medical Care Clinic NEW SMILE DENTA SPA Clinic Noor Clinic Clinic Oman Provider Clinic ROYAL CITY CLINIC - JLEEB Clinic ROYALE HAYAT MAHBOULA CLINIC Clinic Salhiya Medical pavilion Clinic Shaab Medical Center Clinic SHIFA AL JAZEERA M.C.-FARWANIYA Clinic Shifa Al Jazeera Medical Center, FAHAHEEL Clinic VILLA MEDICA Clinic Yiaco Apollo -

Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, And

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2015 Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, and Functions of Green Space in Kuwait City From 1982-2014 Yousif Abdullah University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Physical and Environmental Geography Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Abdullah, Yousif, "Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, and Functions of Green Space in Kuwait City From 1982-2014" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1116. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, and Functions Of Green Space in Kuwait City From 1982-2014. Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, and Functions Of Green Space in Kuwait City From 1982-2014. A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Art in Geography By Yousif Abdullah Kuwait University Bachelor of art in GIS/Geography, 2011 Kuwait University Master of art in Geography May 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________ Dr. Ralph K. Davis Chair ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. Thomas R. Paradise Dr. Fiona M. Davidson Thesis Advisor Committee Member ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. Mohamed Aly Dr. Carl Smith Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT This research assessed green space morphology in Kuwait City, explaining its evolution from 1982 to 2014, through the use of geo-informatics, including remote sensing, geographic information systems (GIS), and cartography. -

Globemed Kuwait Network of Providers Exc KSEC and BAYAN

GlobeMed Kuwait Network of HealthCare Providers As of June 2021 Phone ﺍﻻﺳﻡ ProviderProvider Name Name Region Region Phone Number FFaxax Number Number Hospitals 22573617 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺳﻼﻡ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ Al Salam International Hospital Bnaid Al Gar 22232000 22541930 23905538 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻟﻧﺩﻥ London Hospital Al Fintas 1 883 883 23900153 22639016 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺩﺍﺭ ﺍﻟﺷﻔﺎء Dar Al Shifa Hospital Hawally 1802555 22626691 25314717 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻬﺎﺩﻱ Al Hadi Hospital Jabriya 1828282 25324090 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻌﺭﻑ Al Orf Hospital Al Jahra 2455 5050 2456 7794 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺭﻭﻳﺎﻝ ﺣﻳﺎﺓ Royale Hayat Hospital Jabriya 25360000 25360001 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻋﺎﻟﻳﺔ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ Alia International Hospital Mahboula 22272000 23717020 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺳﺩﺭﺓ Sidra Hospital Al Reggai 24997000 24997070 1881122 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺳﻳﻑ Al Seef Hospital Salmiya 25719810 25764000 25747590 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻣﻭﺍﺳﺎﺓ ﺍﻟﺟﺩﻳﺩ New Mowasat Hospital Salmiya 25726666 25738055 25529012 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻁﻳﺑﺔ Taiba Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 1808088 25528693 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻛﻭﻳﺕ Kuwait Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 22207777 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻭﺍﺭﺓ Wara Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 1888001 ﺍﻟﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ International Hospital Salmiya 1817771 This network is subject to continuous revision by addition/deletion of provider(s) and/or inclusion/exclusion of doctor(s)/department(s) Page 1 of 23 GlobeMed Kuwait Network of HealthCare Providers As of June 2021 Phone ﺍﻻﺳﻡ ProviderProvider Name Name Region Region Phone Number FaxFax Number Number Medical Centers ﻣﺳﺗﻭﺻﻑ ﻣﻳﺩﻳﻛﺎﻝ ﻭﻥ ﺍﻟﺗﺧﺻﺻﻲ Medical one Polyclinic Al Da'iyah 22573883 22574420 1886699 ﻋﻳﺎﺩﺓ ﻧﻭﺭ Noor Clinic Al Ageila 23845957 23845951 22620420 ﻣﺭﻛﺯ ﺍﻟﺷﻌﺏ ﺍﻟﺗﺧﺻﺻﻲ -

Indicators of Urban Health in the Youth Population of Kuwait City and Jahra, Kuwait

Indicators of urban health in the youth population of Kuwait City and Jahra, Kuwait Fayez Alzarban A thesis submitted to the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Public Health) at the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences March: 2018 Declaration No portion of the work in this thesis has been submitted in support of an application for any degree or qualification of the University of Liverpool or any other University or institute of learning. Signature Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking my outstanding supervisors at the University of Liverpool: Dr. Daniel Pope and Dr. Debbi Stanistreet, for their constant support, dedication, and encouragement throughout my study period. I am also grateful for all the help I have received from my academic advisors allocated by the Postgraduate team: Prof. Dame Margaret Whitehead, Prof. Sally Sheard, Prof. David Taylor- Robinson, and Prof. Martin O’Flaherty, for all the advice and guidance they have given me. I would also like to thank Prof. Susan Higham for tremendous support at a very difficult period during my studies. In Kuwait, I would like to extend my thanks to Dr. Jafaar Dawood, the head of the Department of Public Health at the Ministry of Health (Kuwait), for his support in every step of this research in Kuwait. Without his exceptional efforts, this project would have not been possible. I would also like to thank the health inspectors at the Department of Health (Kuwait) for their generosity and dedication in conducting the survey with me: Basim Awkal, MS. Allimby, Ala’a Jaad, Saleh Mohammed, Michelle Asaad, Sarah Alazmi, and Hesa Alali. -

List of UN Examining Physicians Worldwide (Updated December 2016)

List of UN Examining Physicians Worldwide (Updated December 2016) Country City LastName FirstName Specialty Address WorkPhone FaxNumber Email Region Updated AFGHANISTAN JALALABAD ALAM Mohammad Ismail Int. Med. & Card. Dr. M. Ismail Alam Private Clinic, Arab Street, 3419 Not provided Asia and Oceania 06-Jun-14 Near Spinghar Hotel AFGHANISTAN MAZAR-I-SHARIF SHAHIM Abdul Baqi Not provided Balkh Hospital Not provided Not provided Asia and Oceania 06-Jun-14 ALBANIA TIRANA KACI Ledia Internal Medicine & Pediatrics ABC Health Foundation 355 (0)4 2234 105 (3554) 259934 [email protected] [email protected] Europe and The 17-Nov-16 Rruga "Qemal Stafa", Nr. 260, Commonwealth of ALBANIA TIRANA DOBI Drini Neurology University Hospital Center "Mother Tereza", 355 682 078 800 Europe and The 17-Nov-16 Service of Neurology, Commonwealth of ALBANIA TIRANA SELMANI Edvin Orthopedic & Trauma Surgeon Salus Hospital 355 4 2390500 Europe and The 17-Nov-16 Rruga Vidhe Gjata 16, Commonwealth of ALBANIA TIRANA HOXHAJ Enkeleta General Medicine Medical Response for the Diplomatic Corps 355 (0) 407 2392 [email protected] Europe and The 17-Nov-16 (MRDC) Commonwealth of ALGERIA ALGIERS ABROUS MESSAR Roneida General Practice Clinique medico diagnostic du val lot 11 551118218 21946687 [email protected] Arab States 15-Aug-16 decembre val d’hydra ALGERIA ALGIERS GHENIM Reda General Practice 7, rue Henri Dunant (ex. Mulhouse) (213) 02 72 63 53 Not provided Arab States 31-Mar-15 ALGERIA TINDOUF DJAKANI Mustapha General Practice Tindouf (213) 661 27 83 -

Domestic Workers' Legal Guide

ENGLISH Kuwait’s National Awareness Campaign on the Rights of Domestic Workers’ Domestic Workers and Employers Legal Guide Organized By In Partnership With Table of Contents Assault 26 Shelter 41 Sexual Assault 28 Types of Residency 42 Financial Matters 4 Advice on Residency Law 32 Numbers & Places of Interest 43 Living Conditions 8 Legal Advice 33 Embassies & Consulates in Kuwait 44 Location & Nature of Work 12 Legal Procedures 34 Embassies & Consulates Outside Kuwait 48 Working Hours & Holidays 16 Guarantees for Suspect 35 Investigation Departments 50 General Labour Rights 18 Deportation & Absconding 36 Public Prosecution 51 Duties of Domestic Workers 20 Remand 37 Police Stations 52 General Rights 21 Criminal Complaints 38 E-services 62 Kidnap & False Imprisonment 22 Labour Complaint 40 Laws 63 About One Roof Campaign “One Roof” is a campaign that aims to raise awareness about domestic workers’ rights. This campaign is a partnership between the Human Line Organization and the Social Work Society in collaboration with the Ministry of Interior and other international organizations. “One Roof” Campaign works toward building a positive relationship between the employer and domestic worker that is governed by justice and serves to protect the rights and dignity of both parties. The campaign aims to raise awareness about domestic workers’ rights as stated in Kuwaiti laws to reduce conflict and problems that may arise due to the lack of awareness of laws that regulate the work of domestic workers in Kuwait. “One Roof” also seeks to emphasize that domestic work is an occupation that should be regulated by laws and procedures. About the Legal Guide While the relationship between the employer and domestic worker in Kuwait is successful and effective in most cases, it is still important for domestic workers to be knowledgeable of their legal rights and responsibilities in order to be familiar with the rules that regulate their work and be able to demand their rights in case they were violated. -

Of Visa Trade Victims in Time of Pandemic Sold out

ARAB TIMES, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 21, 2021 3 Weather Expected weather for the next with light to moderate north west- Bubyan - - Prayer Timings 24 hours: erly wind to light variable wind Jahra 40 23 Fajr ........ 03:53 Asr .......... 15:22 By Day: Hot and partly cloudy with speeds of 06-24 km/h. Salmiyah 35 28 Sunrise .. 05:16 Maghrib .. 18:17 with light variable wind to light Station Max Exp Min Rec Ahmadi 37 27 Zohr ....... 11:48 Isha ........19:38 to moderate north westerly wind Kuwait City 38 28 Nuwaisib 41 21 with speeds of 08-30 km/h. Kuwait Airport 39 21 Wafra 40 20 By Night: Fair and partly cloudy Abdaly 40 21 Salmy 39 21 VACCINE REGISTRATION WEBSITE: https://cov19vaccine.moh.gov.kw/SPCMS/CVD_19_Vaccine_Registration.aspx KFH rallies 7 fils, Humansoft Holding retreats Kuwait’s All Shares Index breaches 6,000 mark, volume soars By John Mathews fi ls. National Investment Co rose 4 fi ls to 189 fi ls ing in some of the heavyweights and mid-caps fi ls and International Financial Advisors re- and KIPCO paced 3 fi ls with a volume of 5.6 and closed with hefty gains. treated 3 fi ls. Coast Investment ticked 1.6 fi ls ▼ UUS$/KDS$/KD 00.30105/15.30105/15 Arab Times Staff million to end at 165 fi ls. Tamdeen Investment Top gainer of the day, Kuwait Reinsurance up and KMEFIC climbed 5 fi ls to 144 fi ls. KUWAIT CITY, April 20: Kuwait stocks climbed 8 fi ls to 224 fi ls and Kuwait Reinsurance Co spiked 9.84 percent to 424 fi ls and Mubarrad First Investment gave up 2.1 fi ls after trading ▲ Euro/KD 0.3634 breached the 6,000 pts benchmark on Tues- Co soared 38 fi ls with thin trading. -

Radiological Conditions in Areas of Kuwait with Residues of Depleted Uranium

RADIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT REPORTS SERIES Radiological Conditions in Areas of Kuwait with Residues of Depleted Uranium Report by an international group of experts IAEA SAFETY RELATED PUBLICATIONS IAEA SAFETY STANDARDS Under the terms of Article III of its Statute, the IAEA is authorized to establish standards of safety for protection against ionizing radiation and to provide for the application of these standards to peaceful nuclear activities. The regulatory related publications by means of which the IAEA establishes safety standards and measures are issued in the IAEA Safety Standards Series. This series covers nuclear safety, radiation safety, transport safety and waste safety, and also general safety (that is, of relevance in two or more of the four areas), and the categories within it are Safety Fundamentals, Safety Requirements and Safety Guides. Safety Fundamentals (blue lettering) present basic objectives, concepts and principles of safety and protection in the development and application of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. Safety Requirements (red lettering) establish the requirements that must be met to ensure safety. These requirements, which are expressed as ‘shall’ statements, are governed by the objectives and principles presented in the Safety Fundamentals. Safety Guides (green lettering) recommend actions, conditions or procedures for meeting safety requirements. Recommendations in Safety Guides are expressed as ‘should’ state- ments, with the implication that it is necessary to take the measures recommended or equivalent alternative measures to comply with the requirements. The IAEA’s safety standards are not legally binding on Member States but may be adopted by them, at their own discretion, for use in national regulations in respect of their own activities.