High Contrast Imaging Goals and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nearest Stars: a Guided Tour by Sherwood Harrington, Astronomical Society of the Pacific

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 5 - Spring 1986 © 1986, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. The Nearest Stars: A Guided Tour by Sherwood Harrington, Astronomical Society of the Pacific A tour through our stellar neighborhood As evening twilight fades during April and early May, a brilliant, blue-white star can be seen low in the sky toward the southwest. That star is called Sirius, and it is the brightest star in Earth's nighttime sky. Sirius looks so bright in part because it is a relatively powerful light producer; if our Sun were suddenly replaced by Sirius, our daylight on Earth would be more than 20 times as bright as it is now! But the other reason Sirius is so brilliant in our nighttime sky is that it is so close; Sirius is the nearest neighbor star to the Sun that can be seen with the unaided eye from the Northern Hemisphere. "Close'' in the interstellar realm, though, is a very relative term. If you were to model the Sun as a basketball, then our planet Earth would be about the size of an apple seed 30 yards away from it — and even the nearest other star (alpha Centauri, visible from the Southern Hemisphere) would be 6,000 miles away. Distances among the stars are so large that it is helpful to express them using the light-year — the distance light travels in one year — as a measuring unit. In this way of expressing distances, alpha Centauri is about four light-years away, and Sirius is about eight and a half light- years distant. -

![Arxiv:1809.07342V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 19 Sep 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6323/arxiv-1809-07342v1-astro-ph-sr-19-sep-2018-96323.webp)

Arxiv:1809.07342V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 19 Sep 2018

Draft version September 21, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 11/10/09 FAR-ULTRAVIOLET ACTIVITY LEVELS OF F, G, K, AND M DWARF EXOPLANET HOST STARS* Kevin France1, Nicole Arulanantham1, Luca Fossati2, Antonino F. Lanza3, R. O. Parke Loyd4, Seth Redfield5, P. Christian Schneider6 Draft version September 21, 2018 ABSTRACT We present a survey of far-ultraviolet (FUV; 1150 { 1450 A)˚ emission line spectra from 71 planet- hosting and 33 non-planet-hosting F, G, K, and M dwarfs with the goals of characterizing their range of FUV activity levels, calibrating the FUV activity level to the 90 { 360 A˚ extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) stellar flux, and investigating the potential for FUV emission lines to probe star-planet interactions (SPIs). We build this emission line sample from a combination of new and archival observations with the Hubble Space Telescope-COS and -STIS instruments, targeting the chromospheric and transition region emission lines of Si III,N V,C II, and Si IV. We find that the exoplanet host stars, on average, display factors of 5 { 10 lower UV activity levels compared with the non-planet hosting sample; this is explained by a combination of observational and astrophysical biases in the selection of stars for radial-velocity planet searches. We demonstrate that UV activity-rotation relation in the full F { M star sample is characterized by a power-law decline (with index α ≈ −1.1), starting at rotation periods & 3.5 days. Using N V or Si IV spectra and a knowledge of the star's bolometric flux, we present a new analytic relationship to estimate the intrinsic stellar EUV irradiance in the 90 { 360 A˚ band with an accuracy of roughly a factor of ≈ 2. -

Materials Challenges for the Starshot Lightsail

PERSPECTIVE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-018-0075-8 Materials challenges for the Starshot lightsail Harry A. Atwater 1*, Artur R. Davoyan1, Ognjen Ilic1, Deep Jariwala1, Michelle C. Sherrott 1, Cora M. Went2, William S. Whitney2 and Joeson Wong 1 The Starshot Breakthrough Initiative established in 2016 sets an audacious goal of sending a spacecraft beyond our Solar System to a neighbouring star within the next half-century. Its vision for an ultralight spacecraft that can be accelerated by laser radiation pressure from an Earth-based source to ~20% of the speed of light demands the use of materials with extreme properties. Here we examine stringent criteria for the lightsail design and discuss fundamental materials challenges. We pre- dict that major research advances in photonic design and materials science will enable us to define the pathways needed to realize laser-driven lightsails. he Starshot Breakthrough Initiative has challenged a broad nanocraft, we reveal a balance between the high reflectivity of the and interdisciplinary community of scientists and engineers sail, required for efficient photon momentum transfer; large band- Tto design an ultralight spacecraft or ‘nanocraft’ that can reach width, accounting for the Doppler shift; and the low mass necessary Proxima Centauri b — an exoplanet within the habitable zone of for the spacecraft to accelerate to near-relativistic speeds. We show Proxima Centauri and 4.2 light years away from Earth — in approxi- that nanophotonic structures may be well-suited to meeting such mately -

Prospects of Detecting the Polarimetric Signature of the Earth-Mass Planet Α Centauri B B with SPHERE/ZIMPOL

A&A 556, A64 (2013) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201321881 & c ESO 2013 Astrophysics Prospects of detecting the polarimetric signature of the Earth-mass planet α Centauri B b with SPHERE/ZIMPOL J. Milli1,2, D. Mouillet1,D.Mawet2,H.M.Schmid3, A. Bazzon3, J. H. Girard2,K.Dohlen4, and R. Roelfsema3 1 Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG), University Joseph Fourier, CNRS, BP 53, 38041 Grenoble, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 European Southern Observatory, Casilla 19001, Santiago 19, Chile 3 Institute for Astronomy, ETH Zurich, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland 4 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille (LAM),13388 Marseille, France Received 12 May 2013 / Accepted 4 June 2013 ABSTRACT Context. Over the past five years, radial-velocity and transit techniques have revealed a new population of Earth-like planets with masses of a few Earth masses. Their very close orbit around their host star requires an exquisite inner working angle to be detected in direct imaging and sets a challenge for direct imagers that work in the visible range, such as SPHERE/ZIMPOL. Aims. Among all known exoplanets with less than 25 Earth masses we first predict the best candidate for direct imaging. Our primary objective is then to provide the best instrument setup and observing strategy for detecting such a peculiar object with ZIMPOL. As a second step, we aim at predicting its detectivity. Methods. Using exoplanet properties constrained by radial velocity measurements, polarimetric models and the diffraction propaga- tion code CAOS, we estimate the detection sensitivity of ZIMPOL for such a planet in different observing modes of the instrument. -

The Search for Another Earth – Part II

GENERAL ARTICLE The Search for Another Earth – Part II Sujan Sengupta In the first part, we discussed the various methods for the detection of planets outside the solar system known as the exoplanets. In this part, we will describe various kinds of exoplanets. The habitable planets discovered so far and the present status of our search for a habitable planet similar to the Earth will also be discussed. Sujan Sengupta is an 1. Introduction astrophysicist at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bengaluru. He works on the The first confirmed exoplanet around a solar type of star, 51 Pe- detection, characterisation 1 gasi b was discovered in 1995 using the radial velocity method. and habitability of extra-solar Subsequently, a large number of exoplanets were discovered by planets and extra-solar this method, and a few were discovered using transit and gravi- moons. tational lensing methods. Ground-based telescopes were used for these discoveries and the search region was confined to about 300 light-years from the Earth. On December 27, 2006, the European Space Agency launched 1The movement of the star a space telescope called CoRoT (Convection, Rotation and plan- towards the observer due to etary Transits) and on March 6, 2009, NASA launched another the gravitational effect of the space telescope called Kepler2 to hunt for exoplanets. Conse- planet. See Sujan Sengupta, The Search for Another Earth, quently, the search extended to about 3000 light-years. Both Resonance, Vol.21, No.7, these telescopes used the transit method in order to detect exo- pp.641–652, 2016. planets. Although Kepler’s field of view was only 105 square de- grees along the Cygnus arm of the Milky Way Galaxy, it detected a whooping 2326 exoplanets out of a total 3493 discovered till 2Kepler Telescope has a pri- date. -

A Proxy for Stellar Extreme Ultraviolet Fluxes

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. main ©ESO 2020 November 2, 2020 Ca ii H&K stellar activity parameter: a proxy for stellar Extreme Ultraviolet Fluxes A. G. Sreejith1, L. Fossati1, A. Youngblood2, K. France2, and S. Ambily2 1 Space Research Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Schmiedlstrasse 6, 8042 Graz, Austria e-mail: [email protected] 2 Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, UCB 600, Boulder, CO, 80309, USA Received date / Accepted date ABSTRACT Atmospheric escape is an important factor shaping the exoplanet population and hence drives our understanding of planet formation. Atmospheric escape from giant planets is driven primarily by the stellar X-ray and extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) radiation. Furthermore, EUV and longer wavelength UV radiation power disequilibrium chemistry in the middle and upper atmosphere. Our understanding of atmospheric escape and chemistry, therefore, depends on our knowledge of the stellar UV fluxes. While the far-ultraviolet fluxes can be observed for some stars, most of the EUV range is unobservable due to the lack of a space telescope with EUV capabilities and, for the more distant stars, to interstellar medium absorption. Thus, it becomes essential to have indirect means for inferring EUV fluxes from features observable at other wavelengths. We present here analytic functions for predicting the EUV emission of F-, G-, K-, and M-type ′ stars from the log RHK activity parameter that is commonly obtained from ground-based optical observations of the ′ Ca ii H&K lines. The scaling relations are based on a collection of about 100 nearby stars with published log RHK and EUV flux values, where the latter are either direct measurements or inferences from high-quality far-ultraviolet (FUV) spectra. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

ISPY-NACO Imaging Survey for Planets Around Young Stars Survey Description and Results from the first 2.5 Years of Observations? R

A&A 635, A162 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937000 & © R. Launhardt et al. 2020 Astrophysics ISPY-NACO Imaging Survey for Planets around Young stars Survey description and results from the first 2.5 years of observations? R. Launhardt1, Th. Henning1, A. Quirrenbach2, D. Ségransan3, H. Avenhaus4,1, R. van Boekel1, S. S. Brems2, A. C. Cheetham1,3, G. Cugno4, J. Girard5, N. Godoy8,11, G. M. Kennedy6, A.-L. Maire1,10, S. Metchev7, A. Müller1, A. Musso Barcucci1, J. Olofsson8,11, F. Pepe3, S. P. Quanz4, D. Queloz9, S. Reffert2, E. L. Rickman3, H. L. Ruh2, and M. Samland1,12 1 Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Landessternwarte, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Königstuhl 12, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 3 Observatoire Astronomique de l’Université de Genève, 51 Ch. des Maillettes, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland 4 ETH Zürich, Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Wolfgang-Pauli-Str. 27, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland 5 Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore 21218, MD, USA 6 Department of Physics & Centre for Exoplanets and Habitability, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK 7 The University of Western Ontario, Department of Physics and Astronomy, 1151 Richmond Avenue, London, ON N6A 3K7, Canada 8 Instituto de Física y Astronomía, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Valparaíso, Av. Gran Bretaña 1111, Playa Ancha, Valparaíso, Chile 9 Cavendish Laboratory, J J Thomson Avenue, Cambridge, CB3 0HE, UK 10 STAR Institute, University of Liège, Allée du Six Août 19c, 4000 Liège, Belgium 11 Núcleo Milenio Formación Planetaria – NPF, Universidad de Valparaíso, Av. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Observing Exoplanets

Observing Exoplanets Olivier Guyon University of Arizona Astrobiology Center, National Institutes for Natural Sciences (NINS) Subaru Telescope, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, National Institutes for Natural Sciences (NINS) Nov 29, 2017 My Background Astronomer / Optical scientist at University of Arizona and Subaru Telescope (National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Telescope located in Hawaii) I develop instrumentation to find and study exoplanet, for ground-based telescopes and space missions My interest is focused on habitable planets and search for life outside our solar system At Subaru Telescope, I lead the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics (SCExAO) instrument. 2 ALL known Planets until 1989 Approximately 10% of stars have a potentially habitable planet 200 billion stars in our galaxy → approximately 20 billion habitable planets Imagine 200 explorers, each spending 20s on each habitable planet, 24hr a day, 7 days a week. It would take >60yr to explore all habitable planets in our galaxy alone. x 100,000,000,000 galaxies in the observable universe Habitable planets Potentially habitable planet : – Planet mass sufficiently large to retain atmosphere, but sufficiently low to avoid becoming gaseous giant – Planet distance to star allows surface temperature suitable for liquid water (habitable zone) Habitable zone = zone within which Earth-like planet could harbor life Location of habitable zone is function of star luminosity L. For constant stellar flux, distance to star scales as L1/2 Examples: Sun → habitable zone is at ~1 AU Rigel (B type star) Proxima Centauri (M type star) Habitable planets Potentially habitable planet : – Planet mass sufficiently large to retain atmosphere, but sufficiently low to avoid becoming gaseous giant – Planet distance to star allows surface temperature suitable for liquid water (habitable zone) Habitable zone = zone within which Earth-like planet could harbor life Location of habitable zone is function of star luminosity L. -

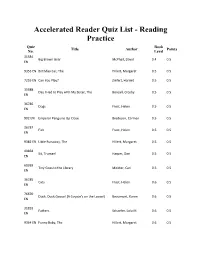

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 31584 Big Brown Bear McPhail, David 0.4 0.5 EN 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet 0.5 0.5 35988 Day I Had to Play with My Sister, The Bonsall, Crosby 0.5 0.5 EN 36786 Dogs Frost, Helen 0.5 0.5 EN 902 EN Emperor Penguins Up Close Bredeson, Carmen 0.5 0.5 36787 Fish Frost, Helen 0.5 0.5 EN 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 49858 Sit, Truman! Harper, Dan 0.5 0.5 EN 60939 Tiny Goes to the Library Meister, Cari 0.5 0.5 EN 36785 Cats Frost, Helen 0.6 0.5 EN 76670 Duck, Duck,Goose! (A Coyote's on the Loose!) Beaumont, Karen 0.6 0.5 EN 31833 Fathers Schaefer, Lola M. 0.6 0.5 EN 9364 EN Funny Baby, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9383 EN Magic Beans, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 83514 Puppy Mudge Finds a Friend Rylant, Cynthia 0.6 0.5 EN 88312 Puppy Mudge Wants to Play Rylant, Cynthia 0.6 0.5 EN 59439 Rosie's Walk Hutchins, Pat 0.6 0.5 EN 9391 EN Three Bears, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9392 EN Three Goats, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9393 EN Three Little Pigs, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9400 EN Yellow Boat, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9355 EN Cinderella at the Ball Hillert, Margaret 0.7 0.5 31818 Family Pets Schaefer, Lola M. -

A New Form of Estimating Stellar Parameters Using an Optimization Approach

A&A 532, A20 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200811182 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Modeling nearby FGK Population I stars: A new form of estimating stellar parameters using an optimization approach J. M. Fernandes1,A.I.F.Vaz2, and L. N. Vicente3 1 CFC, Department of Mathematics and Astronomical Observatory, University of Coimbra, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Production and Systems, University of Minho, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] 3 CMUC, Department of Mathematics, University of Coimbra, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] Received 17 October 2008 / Accepted 27 May 2011 ABSTRACT Context. Modeling a single star with theoretical stellar evolutionary tracks is a nontrivial problem because of a large number of unknowns compared to the number of observations. A current way of estimating stellar age and mass consists of using interpolations in grids of stellar models and/or isochrones, assuming ad hoc values for the mixing length parameter and the metal-to-helium enrichment, which is normally scaled to the solar values. Aims. We present a new method to model the FGK main-sequence of Population I stars. This method is capable of simultaneously estimating a set of stellar parameters, namely the mass, the age, the helium and metal abundances, the mixing length parameter, and the overshooting. Methods. The proposed method is based on the application of a global optimization algorithm (PSwarm) to solve an optimization problem that in turn consists of finding the values of the stellar parameters that lead to the best possible fit of the given observations.