Project Against Corruption in Albania (Paca)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings 2013

Proceedings International Conference www.isa-sociology.org; www.europeansociology.org; www.instituti-sociologjise.al; Organizers: Albanian Institute of Sociology (AIS) Ministry of Education and Sports, Albania University Aleksander Moisiu of Durres – Albania Municipality of Durres, Albania University Academy of Applied Studies, Durres-Albania (Talenti Ed. Group) Democracy in Times of Turmoil; a multidimensional approach Durres-Albania 22-23 November 2013 © Albanian Institute of Sociology (AIS) Ed: Lekë SOKOLI & Elda KUTROLLI Design: Orest MUÇA Contacts: Mobile: ++355(0)694067682; ++355(0)692032731; ++355(0)696881188 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; www.instituti-sociologjise.al; Last International Conference of the Albanian Institute of Sociology On 100 Anniversary of the Albanian Independence Proceedings International Interdisciplinary Conference Vlora-Albania 26-28 November 2012 Albanian Institute of Sociology (AIS) University Ismail Qemali of Vlora Albanian University, Tirana University Pavaresia of Vlora Universitety Reald, Vlora University Marin Barleti, Tirana “AULEDA” Local Economic Development Agency International School, Vlora CONFERENCE THEMES: Central Theme: “Identity, Image & Social Cohesion in the time of Integrations and Globalization” Other themes: by 15 Thematic Sections Special Session: The application of modern methods in aquatic environment research •410 Participants • 22 countries • plenary session • a special session • 61 parallel thematic sessions • Contents: I. General Conference Program -

Judicial Corruption in Eastern Europe: an Examination of Causal Mechanisms in Albania and Romania Claire M

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2017 Judicial corruption in Eastern Europe: An examination of causal mechanisms in Albania and Romania Claire M. Swinko James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Swinko, Claire M., "Judicial corruption in Eastern Europe: An examination of causal mechanisms in Albania and Romania" (2017). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 334. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/334 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judicial Corruption in Eastern Europe: An Examination of Causal Mechanisms in Albania and Romania _______________________ An Honors Program Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ by Claire Swinko May 2017 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of Political Science, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Program. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS PROGRAM APPROVAL: Project Advisor: John Hulsey, Ph.D., Bradley R. Newcomer, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Political Science Director, Honors Program Reader: John Scherpereel, Ph.D., Professor, Political Science Reader: Charles Blake, Ph. D., Professor, Political Science Dedication For my dad, who supports and inspires me everyday. You taught me to shoot for the stars, and I would not be half the person I am today with out you. -

Development of Environmental Code of Conduct in Dajti National Park

DEVELOPMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL CODE OF CONDUCT IN DAJTI NATIONAL PARK Sindi Lilo1, Raimonda Totoni2 1Department of Environmental Engineering, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Polytechnic University of Tirana, ALBANIA, e-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Mathematical Engineering and Physical Engineering, Polytechnic University of Tirana, ALBANIA, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Dajti National Park is one of the main Natural National Parks in Albania. This Protected Area is situated in the East of Tirana and covers an area of 29217 ha. Dajti National Park is very important on local, national and regional level, for its biodiversity, landscape, recreational and cultural values. Among others it is considered as a live museum of the natural vertical structure of vegetation. The heritage, traditions on ethnography, music, cooking, hospitality etc, unique on Central Albania region, are some other local cultural values that from centuries runs in compliance with natural richness. Unfortunately, for more than 20 years, because of the demographic changes and human stresses caused by it, the National Park values are threatened and reduced by uncontrolled human activity. Forest fires, erosion, inappropriate solid waste disposal, etc. can be counted between main negative impacts caused by human intervention in the area. Unplanned tourism and missing of an appropriate and integrated management is threatening the remained values of this important site. In this condition developing and adopting of Environmental Code of Conduct in Dajti Park is necessary and would contribute in development of ecotourism as an important tool for conservation of natural and cultural resource and for sustainable development. This Code consists on definition of the framework for protection of natural and human values instead of their overexploitation for short term purposes. -

Identification of Microorganisms in Fresh and Dried Fruits Cultivated, Imported and Consumed in Tirana City

Albanian j. agric. sci. 2014;13 (4):18-25 Agricultural University of Tirana RESEARCH ARTICLE (Open Access) Identification of Microorganisms in Fresh and Dried Fruits Cultivated, Imported and Consumed in Tirana City OLTIANA PETRI1, ARBEN LUZATI1, ANJEZA ÇOKU1, TOMI PETRI2, SILVANA MARDHA1, ERJONA ABAZAJ1 1Institute of Public Health, Tirana, Albania 2“Ungjillezimi” Clinic, Tirana, Albania Abstract Fruits products contamination present a particular concern for human health, since many of these products are raw consumed without any prior treatment, which would eliminate or reduce biological, microbiological or physical risks. The aim of this study is to gather basic information on microbiological quality in fresh and dried fruits, which are traded currently in Tirana, as this city presents almost one third of Albania. This study was conducted during the period November 2010-March 2013 in Tirana's main markets. In total were collected 257 samples, 174 samples are dried fruit and 83 samples are fresh fruit. Each sample of fresh fruits was analyzed for bacteria, molds and yeast, but dried fruits were analyzed only for molds and yeast. In fresh fruits we didn`t found Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus, but we detected presence of Aerobic mesophilic count plate 1.2%, Coliform total 2.4% and E. coli 1.2%. Also we found presence of mold and yeast for potential health hazard in 4.8% and 2.4% respectivilly. The results for dried fruits were 22.4% of them have indicated potential health hazard with mold, while yeast in 8.6%. Mold and yeast were the most frequent contaminants of fresh and dried fruits sold in trades of Tirana. -

“Public Space” in Tirana Eduina Zekaj Polytechnic University of Tirana, [email protected]

University of Business and Technology in Kosovo UBT Knowledge Center UBT International Conference 2017 UBT International Conference Oct 27th, 1:00 PM - 2:30 PM The development of the concept of “public space” in Tirana Eduina Zekaj Polytechnic University of Tirana, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecenter.ubt-uni.net/conference Part of the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Zekaj, Eduina, "The development of the concept of “public space” in Tirana" (2017). UBT International Conference. 4. https://knowledgecenter.ubt-uni.net/conference/2017/all-events/4 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Publication and Journals at UBT Knowledge Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in UBT International Conference by an authorized administrator of UBT Knowledge Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Development of the Concept of “Public Space” in Tirana Eduina Zekaj Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, Polytechnic University of Tirana, Albania Abstract. The term “public space”, also known as urban space is a pretty old phrase, but was used as e concept with a clear definition during the modern era. The evolution of this term is well known in Tirana, because of its constant development especially in the recent projects. The first attempts started in 1914, but by that time there did not exist a real concept of the public space, which accordingly was affected by the citizens’ lifestyle. Public spaces in Tirana have changed a lot since then by recreating the concept of “public use”. There are many examples of squares, streets and parks which have gone through the process of change over the years and have affected people’s lives. -

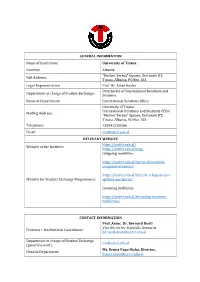

GENERAL INFORMATION Name of Institution: University of Tirana

GENERAL INFORMATION Name of Institution: University of Tirana Country: Albania ”Mother Teresa” Square, Rectorate UT, Full Address: Tirana, Albania, PO Box 183 Legal Representative: Prof. Dr. Artan Hoxha Directorate of International Relations and Department in charge of Student Exchange: Students Name of Department: International Relations Office University of Tirana International Relations and Students Office Mailing Address: ”Mother Teresa” Square, Rectorate UT, Tirana, Albania, PO Box 183 Telephone: +35542250166 Email: [email protected] RELEVANT WEBSITE https://unitir.edu.al/ Website of the Institute: https://unitir.edu.al/eng/ Outgoing mobilities https://unitir.edu.al/bursa-shkembimi- programi-erasmus/ https://unitir.edu.al/thirrjet-e-hapura-per- Website for Student Exchange Programmes: aplikim-per-bursa/ Incoming mobilities https://unitir.edu.al/incoming-erasmus- mobilities/ CONTACT INFORMATION Prof. Assoc. Dr. Bernard Dosti Vice Rector for Scientific Research Erasmus + Institutional Coordinator [email protected] Department in charge of Student Exchange [email protected] (general e-mail): Ms. Bruna Papa Niçka, Director, Head of Department: [email protected] [email protected]; Office in charge for all outgoing/incoming [email protected]; mobilities for students and staff (e-mail) Prof. Dr. Artan Hoxha Rector Prof. Assoc. Dr. Bernard Dosti Vice Rector/Erasmus + Institutional Coordinator [email protected]; Ms. Bruna Papa Niçka For the Inter-Institutional Agreements: Director of Internationa Relations and Students Office [email protected] ; International Relations Office [email protected]; International Relations Office [email protected] Visa +35542250166 International Relations Office [email protected] Insurance +35542250166 International Relations Office [email protected] +35542250166 Housing UT cannot guarantee the accommodation in student dormitories due to limited capacities, but will provide information on accommodation possibilities in Tirana. -

From Small-Scale Informal to Investor-Driven Urban Developments

Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft, 162. Jg., S. 65–90 (Annals of the Austrian Geographical Society, Vol. 162, pp. 65–90) Wien (Vienna) 2020, https://doi.org/10.1553/moegg162s65 Busting the Scales: From Small-Scale Informal to Investor-Driven Urban Developments. The Case of Tirana / Albania Daniel Göler, Bamberg, and Dimitër Doka, Tirana [Tiranë]* Initial submission / erste Einreichung: 05/2020; revised submission / revidierte Fassung: 08/2020; final acceptance / endgültige Annahme: 11/2020 with 6 figures and 1 table in the text Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................... 65 Zusammenfassung ............................................................................................................ 66 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 67 2 Research questions and methodology ........................................................................ 71 3 Conceptual focus on Tirana: Moving towards an evolutionary approach .................. 72 4 Large urban developments in Tirana .......................................................................... 74 5 Discussion and problematisation ................................................................................ 84 6 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 86 7 References ................................................................................................................. -

Corruption Assessment Report Albania

CORRUPTION ASSESSMENT REPORT ALBANIA Copyright © 2016, Albanian Center for Economic Research (ACER), South-East Europe Leadership for Development and Integrity (SELDI) Acknowledgments This report was prepared by ACER under guidance from the Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD, Sofia - Bulgaria) within the framework of SELDI network. Research coordination and report preparation: Zef Preci (ACER) Brunilda Kosta (ACER) Eugena Topi (ACER) Lorena Zajmi (ACER) Field research: Fatmir Memaj (Albanian Socio-Economic Think Tank, ASET) Dhimiter Tole (Faculty of Economy, University of Tirana) Sincere thanks are expressed to the staff engaged with dedication and professionalism in the field work carried for the project survey. Project Associates in Albania: House of Europe, Tirana (Albania) Associated partners in Albania: Albanian Media Institute (AMI), Albania Institute for Democracy and Mediation, Albania We would like to acknowledge the contribution to the report of Mr. Ruslan Stefanov (CSD) and Ms Daniela Mineva (CSD). The survey, in which the current report is based, has followed the Corruption Monitoring System methodology. Mr. Alexander Gerganov (Vitosha Research) has provided methodological guidance and instructions in carrying out the survey and delivering the results. This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the SELDI initiative and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. 1 Project Title: Civil Society -

Tirana Municipality TIRANA TRAMWAY PROJECT

Tirana Municipality TIRANA TRAMWAY PROJECT February 2012 Çamlıca / İSTANBUL CONTENTS Page CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ 0 1. LOCATION OF ALBANIA .................................................................................. 0 2. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE CITY BETWEEN 1990 – 2005 .................... 2 3. LOCATION OF TRAMLINES ON STRATEGIC PLAN 2017 OF TIRANA. 4 4. FINANCIAL FEASIBILITY ................................................................................ 7 5. SENSIBILITY ANALYSIS ................................................................................. 11 6. CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................... 12 TABLE LIST Page Table 1 : Historical Population of Tirana. ................................................................... 3 Table 2 : Basic operation parameters .......................................................................... 8 Table 3 : Investment Breakdown for 1st Alternative (with new trains) ....................... 9 Table 4 : Investment Breakdown for 2nd Alternative (with second hand trains) ....... 10 Table 5 : Credit Summary ......................................................................................... 10 Table 6 : Credit Payment Breakdown (with new trains) ............................................... Table 7 : Credit Payment Breakdown (with second hand trains) .................................. Table 8 : Internat rate of -

Democracy in Albania: Shortcomings of Civil Society in Democratization Due to the Communist Regime’S Legacy

Undergraduate Journal of Global Citizenship Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 2 11-25-2014 Democracy in Albania: Shortcomings of Civil Society in Democratization due to the Communist Regime’s Legacy Klevisa Kovaci Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/jogc Recommended Citation Kovaci, Klevisa (2014) "Democracy in Albania: Shortcomings of Civil Society in Democratization due to the Communist Regime’s Legacy," Undergraduate Journal of Global Citizenship: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/jogc/vol2/iss1/2 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Democracy in Albania: Shortcomings of Civil Society in Democratization due to the Communist Regime’s Legacy Cover Page Footnote The author gives a special acknowledgement to Dr. Terry-Ann Jones and Dr. David McFadden of Fairfield University, and to Ms. Elena Shomos for their insights. This article is available in Undergraduate Journal of Global Citizenship: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/jogc/ vol2/iss1/2 Kovaci: Democracy in Albania II. -

Governance in Albania: a Way Forward for Competitiveness, Growth, and European Integration‖ a World Bank Issue Brief

Report No. 62518-AL Public Disclosure Authorized ―Governance in Albania: A Way Forward for Competitiveness, Growth, and European Integration‖ A World Bank Issue Brief June 2011 Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit = ALL (Albanian Lek) ALL 1.00 = US$0.0102859 US$ 1.00 = ALL 97.2200 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES The Metric System is used throughout the report Acronyms AL Albania BEEPS Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey CoE Council of Europe CPI Corruption Perceptions Index CSD Child Survival and Development DP Democratic Party EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EC European Commission ECA Europe and Central Asia EEC European Economic Community EU European Union FDI Foreign Direct Investment FYR Former Yugoslav Republic GDP Gross Domestic Product GNI Gross National Income GRECO Group of States against Corruption HDI Human Development Index IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction and Development IDRA Institute of Development and Research Alternatives IFC International Finance Corporation INSTAT Albanian Statistical Institute INTERPOL International Criminal Police Organization IOM International Options Market ISSR Implementation Support & Supervision Report LSMS Living Standards Measurement Study MDGs Millennium Development Goals NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization NGOs Non-governmental Organization NSDI National Strategy -

Police Corruption

Police Integrity and Corruption in Albania Tirana 2016 Disclaimer: This study was conducted in the framework of the “Police Integrity Index” Project with the support of a grant of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs awarded in the framework of Matra Rule of Law Program. The objectives, proper implementation and results of this project constitute responsibility for the implementing organization – the Institute for Democracy and Mediation. Any views or opinions presented in this project are solely those of the implementing organization and do not necessarily represent those of the Dutch Government. PRINCIPAL RESEARCHER Arjan Dyrmishi RESEARCH GROUP Elona Dhëmbo Gjergji Vurmo Sotiraq Hroni IDM, Tirana 2016 The Institute for Democracy and Mediation would like to thank the Gen- eral Directorate of the State Police for the cooperation and continuous and open communication in the implementation of this project and ac- complishment of its objectives Police Integrity and Corruption in Albania Tirana 2016 Second Edition INSTITUTE FOR DEMOCRACY AND MEDIATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................7 1. Summary of Main Findings .....................................................8 2. Introduction ...........................................................................10 3. Methodology ............................................................................11 3.1 Survey with the Public .............................................................12 3.3 Interviews