Snippets3 Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greenwich Park

GREENWICH PARK CONSERVATION PLAN 2019-2029 GPR_DO_17.0 ‘Greenwich is unique - a place of pilgrimage, as increasing numbers of visitors obviously demonstrate, a place for inspiration, imagination and sheer pleasure. Majestic buildings, park, views, unseen meridian and a wealth of history form a unified whole of international importance. The maintenance and management of this great place requires sensitivity and constant care.’ ROYAL PARKS REVIEW OF GREEWNICH PARK 1995 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD Greenwich Park is England’s oldest enclosed public park, a Grade1 listed landscape that forms two thirds of the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. The parks essential character is created by its dramatic topography juxtaposed with its grand formal landscape design. Its sense of place draws on the magnificent views of sky and river, the modern docklands panorama, the City of London and the remarkable Baroque architectural ensemble which surrounds the park and its established associations with time and space. Still in its 1433 boundaries, with an ancient deer herd and a wealth of natural and historic features Greenwich Park attracts 4.7 million visitors a year which is estimated to rise to 6 million by 2030. We recognise that its capacity as an internationally significant heritage site and a treasured local space is under threat from overuse, tree diseases and a range of infrastructural problems. I am delighted to introduce this Greenwich Park Conservation Plan, developed as part of the Greenwich Park Revealed Project. The plan has been written in a new format which we hope will reflect the importance that we place on creating robust and thoughtful plans. -

Buzzword Members’ Newsletter - March 2017 - Issue 33

Buzzword Members’ newsletter - March 2017 - Issue 33 Saving the sound of summer Bee the revolution and save the sound of summer bumblebeeconservation.org 1 Bee the revolution Those of us besotted by bumblebees, know how vital they are. They have an intrinsic value as well as the much stated economic value, (estimated at £691 million per year to the UK economy). Our members, volunteers and staff are united around the shared purpose of ensuring their existence and conservation. But we need more people to understand, enjoy and cherish our bumblebees, that’s why at the AGM in December I urged everyone in the room to ‘Bee the Revolution’. Photo: Thalia Brown, Together we can ensure our bumblebees flourish. Reversing the Buff-tailed bumblebee trend in their declines, needs a concerted effort by all of us who (Bombus terrestris) are passionate about them. “ Please help by asking friends and family to join the Trust. We can do even MORE to help bumblebees with more supporters. Spread the word, ‘bee the revolution’ and together, we can ‘save the sound of summer’. Thank you. Gill Perkins, CEO You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make. Jane Goodall Contents “4. Trees for bees 8. Companion planting . 16. Solitary bees 4 8 16 Get in touch Cover picture Post Bumblebee Conservation Trust, Beta Centre, Vivian Russell: Red-tailed Stirling University Innovation Park, Stirling FK9 4NF cuckoo bumblebee (Bombus Phone 01786 -

Wild Bees in the Hoeksche Waard

Wild bees in the Hoeksche Waard Wilson Westdijk C.S.G. Willem van Oranje Text: Wilson Westdijk Applicant: C.S.G. Willem van Oranje Contact person applicant: Bart Lubbers Photos front page Upper: Typical landscape of the Hoeksche Waard - Rotary Hoeksche Waard Down left: Andrena rosae - Gert Huijzers Down right: Bombus muscorum - Gert Huijzers Table of contents Summary 3 Preface 3 Introduction 4 Research question 4 Hypothesis 4 Method 5 Field study 5 Literature study 5 Bee studies in the Hoeksche Waard 9 Habitats in the Hoeksche Waard 11 Origin of the Hoeksche Waard 11 Landscape and bees 12 Bees in the Hoeksche Waard 17 Recorded bee species in the Hoeksche Waard 17 Possible species in the Hoeksche Waard 22 Comparison 99 Compared to Land van Wijk en Wouden 100 Species of priority 101 Species of priority in the Hoeksche Waard 102 Threats 106 Recommendations 108 Conclusion 109 Discussion 109 Literature 111 Sources photos 112 Attachment 1: Logbook 112 2 Summary At this moment 98 bee species have been recorded in the Hoeksche Waard. 14 of these species are on the red list. 39 species, that have not been recorded yet, are likely to occur in the Hoeksche Waard. This results in 137 species, which is 41% of all species that occur in the Netherlands. The species of priority are: Andrena rosae, A. labialis, A. wilkella, Bombus jonellus, B. muscorum and B. veteranus. Potential species of priority are: Andrena pilipes, A. gravida Bombus ruderarius B. rupestris and Nomada bifasciata. Threats to bees are: scaling up in agriculture, eutrophication, reduction of flowers, pesticides and competition with honey bees. -

Pollination and Botanic Gardens Contribute to the Next Issue of Roots

Botanic Gardens Conservation International Education Review Volume 17 • Number 1 • May 2020 Pollination and botanic gardens Contribute to the next issue of Roots The next issue of Roots is all about education and technology. As this issue goes to press, most botanic gardens around the world are being impacted by the spread of the coronavirus Covid-19. With many Botanic Gardens Conservation International Education Review Volume 16 • Number 2 • October 2019 Citizen gardens closed to the public, and remote working being required, Science educators are having to find new and innovative ways of connecting with visitors. Technology is playing an ever increasing role in the way that we develop and deliver education within botanic gardens, making this an important time to share new ideas and tools with the community. Have you developed a new and innovative way of engaging your visitors through technology? Are you using technology to engage a Botanic Gardens Conservation International Education Review Volume 17 • Number 1 • April 2020 wider audience with the work of your garden? We are currently looking for a variety of contributions including Pollination articles, education resources and a profile of an inspirational garden and botanic staff member. gardens To contribute, please send a 100 word abstract to [email protected] by 15th June 2020. Due to the global impacts of COVID-19, BGCI’s 7th Global Botanic Gardens Congress is being moved to the Australian spring. Join us in Melbourne, 27 September to 1 October 2021, the perfect time to visit Victoria. Influence and Action: Botanic Gardens as Agents of Change will explore how botanic gardens can play a greater role in shaping our future. -

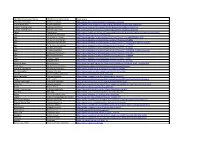

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read More

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read more a European Hoverfly Pocota personata https://www.naturespot.org.uk/species/pocota-personata a small black wasp Stigmus pendulus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/crabronidae/pemphredoninae/stigmus-pendulus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius concinnus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-concinnus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius nigerrimus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-nigerrimus Adder Vipera berus https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/animals/reptiles-and-amphibians/adder/ Alga Cladophora glomerata https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cladophora Alga Closterium acerosum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=x44d373af81fe4f72 Alga Closterium ehrenbergii https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28183 Alga Closterium moniliferum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28227&sk=0&from=results Alga Coelastrum microporum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27402 Alga Cosmarium botrytis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28326 Alga Lemanea fluviatilis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=32651&sk=0&from=results Alga Pediastrum boryanum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27507 Alga Stigeoclonium tenue https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=60904 Alga Ulothrix zonata https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=562 Algae Synedra tenera https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=34482 -

Biodiversity Duty Report 2015-2017

Biodiversity Duty Report 2015-2017 Preamble Under the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act (2004), every public body in Scotland is required to further the conservation of biodiver- sity when carrying out its responsibilities. The Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act (2011) further requires all Scottish pub- lic bodies to provide, every three years, a publicly available report on the actions they have taken to meet the Scottish Biodiversity Duty. Biodiversity is at the heart of the work of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE). Our web page (http://www.rbge.org.uk/), our annual reports and submissions to the Scottish Biodiversity Strate- gy, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation are the primary source of details on our biodiversity science, conservation, horticulture, education and public engagement activities. This report provides an overview of these activities in the period 2015-2017. It also summarises the steps we have taken towards environmentally sustainable management for biodiversity on our own estates. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Biodiversity Report 2015-2017v1.0; Published 31st December 2017 Front cover : A selection of wildlife recorded at RBGE Edinburgh in 2015-2017. Top left Coot ( Fulica atra ). Upper middle left, fly Bibio lanigerus . Lower middle left, Kingfisher ( Alcedo atthis ). Bottom left, barkfly Graphopsocus cruciata . Top right, Merveil- le du Jour ( Griposia aprilina ) (Photo Lucy Cooke). Upper middle right, Spider Aranea diademata with wasp as prey. Lower mid- dle right, Peacock butterfly ( Inachis io ). Bottom right, head end of caterpillar of Elephant Hawk Moth ( Deilephila elpenor). Photos Robert Mill except where otherwise credited. Back cover Grey Heron ( Ardea cinerea ).Photo Robert Mill, RBGE Introduction The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) is a world renowned scientific institution, a centre for plant science and education, and a public attraction. -

Current and Previous Spatial Distributions of Oilseed Rape Fields Influence the Abundance and the Body Size of a Solitary Wild B

RESEARCH ARTICLE Current and previous spatial distributions of oilseed rape fields influence the abundance and the body size of a solitary wild bee, Andrena cineraria, in permanent grasslands Colin Van Reeth1*, GaeÈl Caro1, Christian Bockstaller2, Nadia Michel1 1 Laboratoire Agronomie Environnement (UMR 1121), Universite de Lorraine, INRA, Vandœuvre-lès-Nancy, France, 2 Laboratoire Agronomie Environnement (UMR 1121), INRA, Universite de Lorraine, Colmar, France * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 Wild bees are essential pollinators whose survival partly depends on the capacity of their environment to offer a sufficient amount of nectar and pollen. Semi-natural habitats and mass-flowering crops such as oilseed rape provide abundant floristic resources for bees. The aim of this study was to evaluate the influences of the spatial distribution of semi-natural OPEN ACCESS habitats and oilseed rape fields on the abundance and the mean body size of a solitary bee Citation: Van Reeth C, Caro G, Bockstaller C, in grasslands. We focused on a generalist mining bee, Andrena cineraria, that forages and Michel N (2018) Current and previous spatial reproduces during oilseed rape flowering. In 21 permanent grasslands of Eastern France, distributions of oilseed rape fields influence the we captured 1 287 individuals (1 205 males and 82 females) and measured the body size of abundance and the body size of a solitary wild bee, Andrena cineraria, in permanent grasslands. PLoS male individuals. The flower density in grasslands was quantified during bee captures ONE 13(5): e0197684. https://doi.org/10.1371/ (2016) and the landscape surrounding grasslands was characterized during two consecu- journal.pone.0197684 tive years (2015 and 2016). -

How Much Flower-Rich Habitat Is Enough for Wild Pollinators?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading How much flower-rich habitat is enough for wild pollinators? Answering a key policy question with incomplete knowledge Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Dicks, L. V., Baude, M., Roberts, S. P. M., Phillips, J., Green, M. and Carvell, C. (2015) How much flower-rich habitat is enough for wild pollinators? Answering a key policy question with incomplete knowledge. Ecological Entomology, 40. pp. 22-35. ISSN 0307-6946 doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12226 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/57883/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher's version if you intend to cite from the work. Published version at: http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC4737402 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/een.12226 Publisher: Wiley-Blackwell All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading's research outputs online Ecological Entomology (2015), 40 (Suppl. 1), 22–35 DOI: 10.1111/een.12226 INSECTS AND ECOSYSTEM SERVICES SPECIAL ISSUE How much flower-rich habitat is enough for wild pollinators? Answering a key policy question with incomplete knowledge LYNN V. DICKS,1 MATHILDE BAUDE,2,3 STUART P. -

Recorders' Newsletter

Recorders’ Newsletter Issue 27 – Spring 2019 Welcome to our seasonal round-up of biological recording news in the BIS area. The BIS Recorders Newsletter contains articles written by BIS staff, directors and supporters and the wider biological recording community. Many thanks for all your contributions. It is edited by [email protected] and we hope you enjoy reading it. Janet’s BIS Update 2 What’s the Use of all this Data? 3 to 5 All about Bees 6 Precious Pearls 7 Cultivating a Knowledge in Flowering Plants 8 & 9 Spider Recording at Home 10 & 11 Burial Ground Stories through Biological Records 12 & 13 BMLUP, Black Mountains Land Use Partnership 13 Elan Links 14 & 15 Invaders of the National Park 16 & 17 Where the Wild Things Are 18 Recorder of the Season—John Crellin 19 Have you ‘Add an Adder? 20 & 21 Amman Valley Community Connections 22 & 23 The Sedge Family 24 & 25 The Long Forest 26 & 27 Black Grouse Recovery Project 28 BIS Events & Useful Links 29 to 31 Unit 4, 6 The Bulwark, Brecon, LD3 7LB 01874 610881 [email protected] www.bis.org.uk Facebook: @BISBrecon Twitter: @BISBrecon1 Record you sightings: BIS WiReD & LERC Wales App 1 BIS Update By Janet Imlach, BIS Manager Aderyn Development BIS would like to welcome John Robinson who will be working in the BIS office 1 day per week and at SEWBReC for 2 days. John is a skilled Laravelle developer and will be working on further development of Aderyn to improve resilience for national and local customers of LERC Wales. -

Who's Who of London's Bees

Who’s who of London’s bees LONDON BEEKEEPERS ASSOCIATION The UK has over 275 species of bees, many of which can be found in the Capital – all are important pollinators of food crops and wild plants. Bees vary For more information about the greatly in shape, size and London Beekeepers’ Association and colour and can be found in how you can get involved visit our website or follow us on social media a wide variety of habitats. www.lbka.org.uk Some London parks support up to 50 different [email protected] species so you don’t have @londonbeekeeper to look far to discover a London Beekeepers Association wide range of bees. • Family Halictidae Who’s who of contains the Halictus Bees also known as London’s bees Furrow Bees, the Lassioglossum or Sweat Bees and the While honey bees are currently enjoying a period of Sphecodes or Blood revival and increase in numbers, many of our wild bees Bees, named because continue to struggle to survive. In this leaflet we will of their blood red cover some of the more frequently seen wild bees colouration. Some of Common Yellow Faced Bee found in London. these bees show an UK bees are classified into six families, each containing early form of social behaviour (they are primitively numerous genera and individual species. They are: Eusocial). All have short tongues and prefer simple open flower types. These very small bees are Colletidae • Family , a attracted to garden plants like Astrantia, Alliums, cosmopolitan group Thyme, Eryngium and Solidago. Common examples of short tongued found in London include: Slender Mining Bee bees which nest in Lassioglossum calceatum and the metallic green underground burrows. -

Tormentil Mining Bee on Cornwall Wildlife Trusts Bartinney Nature Reserve Patrick Saunders Nov

Tormentil Mining Bee on Cornwall Wildlife Trusts Bartinney Nature Reserve Patrick Saunders http://www.kernowecology.co.uk/ Nov. 2017 Fig 1. Tormentil Nomad Bee (Nomada roberjeotiana) P. Saunders Patrick Saunders (Kernow Ecology) Entomologist/ Ecological Consultant Pasadena West Looe Hill, Looe Cornwall PL13 2HJ 01503 262567 paddy @kernowecology.co.uk Tormentil Mining Bee on Bartinney Nature Reserve CWT Bartinney Down CWT is one of only 6 sites in the UK where the RDB Tormentil Nomad Bee (Nomada roberjeotiana) has been recently recorded. It is also important for the S.41 Tormentil Mining Bee (Andrena tarsata). • The site has a strong population of Tormentil Mining Bee (A. tarsata) and Tormentil Nomads (N. roberjeotiana) . The highest total count was 51 Tormentil Mining Bee (A. tarsata) and 13 Tormentil Nomads (N. roberjeotiana) on the 26/6/17. • There was a very clear link between Tormentil flower abundance and Tormentil Bee (A. tarsata) abundance, with transects T1 and T4 having abundant Tormentil flowers and abundant Tormentil Bee (A. tarsata) whereas transects T2 and T3 having almost no Tormentil flowers and no Bees. • Ten nest site areas were identified. • Bartinney Down CWT also has a good population of the Buff-tailed Mining Bee (Andrena humilis). The site may be important for its Nationally Scarce cleptoparasite the Cat's Ear Nomad Bee (Nomada integra), which was not recorded. The RDB Perkin's Mining Bee (Andrena rosae) was recorded. The Nationally Scarce Black-headed Mining Bee (Andrena nigriceps) is also present • 35 Bee and Wasp species have been recorded on the site. • 2 Artificial nest sites were created in winter 2016, these were successful with 31 nest holes on N9 In 2017. -

Umass Cranberry Station Research & Extension

UMass Cranberry Station _____________________ Research & Extension Photo by Bob P is licensed under CC BY 2.0 Table of Contents A Review on Bees Title Page Basics & Misconceptions 2 Types of Bees in 3-5 All about bees and how we Massachusetts Bumble Bee Identification 6 can help! Nests 7 Bee Ecology 8 Bees are great. They pollinate our delicious crops, the plants we use to feed livestock, and Bee Food 9 beautiful wildflowers that create not only scenery for Foraging Strategies 10 us, but habitat for wildlife. Their contribution to the Predators, Parasites, and 11-13 ecosystem and to humans is immense. parasitoids Bees are in trouble. Many species of bees are Crop pollination 14 declining. Scientists suggest this decline is due to the rapid environmental changes in the last three Cranberry Pollination 14-16 decades. Bumble Bees and 17 Cranberry Pollination Bees need our help. This handout provides an The Decline of Native 18 overview of bee ecology and behavior, and following Pollinators will be a discussion on what people can do to help. The reader will find planting recommendations based Helping Bees 19-21 on what the author observed our most common native References, Footnotes, 22-26 bees foraging on. Acknowledgements 12 A Review on Bees March 2016 The Basics Misconceptions Telling the difference between flies, wasps, “All bees sting.” There are many and bees is not as easy as it sounds. These species of stingless bees, and male bees do groups of insects are quite similar, and not sting. even experts get it wrong sometimes. “All bees are aggressive.” Bees often Bees have two pairs of wings, their warn before they sting, bumping into the annoyance with their bodies.