Turkish Area Studies Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consuls of the Dardanelles and Gallipoli

1 COLLABORATIVE ONLINE RESEARCH PROJECT Consuls of “THE DARDANELLES” and “GALLIPOLI” (Updated Version no: 4 – February 2013) Welcome to a resource being compiled about the consuls and consulates of “The Dardanelles” and “Gallipoli”. This is an ongoing project. In this fourth update, many new details have been added, especially from genealogical sources, and some questions clarified. The information shown here is not complete and may contain errors. For this reason, it may appear rather haphazard in some places. In time, a more coherent narrative will emerge. The project aims to take advantage of the Internet as a source of information and as a means of communication. There is now a vast and increasing amount of information online which allows us access to sources located in various countries. Many sources are quoted verbatim until the content can be confirmed in comparision with other sources. If you are a researcher, family member, or simply interested in some aspect of this topic, you may be able to help by providing additions, corrections, etc., however short. This will help to fill in gaps and present a fuller picture for the benefit of everybody researching these families or this locality. Comments and contributions should be sent to the following e-mail address: (contact[at]levantineheritagefoundation.org) The information here will be amended in the light of contributions. All contributions will be acknowledged unless you prefer your name not to be mentioned. Many different languages are involved but English is being used as the “lingua franca” in order to reach as many people as possible. Notes in other languages have been and will be included. -

1944 Pan-Turanism Movements: from Cultural Nationalism to Political Nationalism

УПРАВЛЕНИЕ И ОБРАЗОВАНИЕ MANAGEMENT AND EDUCATION TOM V (3) 2009 VOL. V (3) 2009 1944 PAN-TURANISM MOVEMENTS: FROM CULTURAL NATIONALISM TO POLITICAL NATIONALISM A. Baran Dural ДВИЖЕНИЕТО ПАН-ТУРАНИЗЪМ 1944 г.: ОТ КУЛТУРЕН НАЦИОНАЛИЗЪМ КЪМ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКИ НАЦИОНАЛИЗЪМ А. Баран Дурал ABSTRACT: The trial of Turanism in 1944 has a historical importance in terms of nationalism being an ac- tionary movement in Turkish history. When socialism turned out to be a dreadful ideology by getting reactions all over the world, there would not be any more natural attitude than that intellectuals coming from an educa- tion system full of nationalist proposals conflicted with this movement. However, that the same intellectuals crashed the logic of the government saying “if needed, we bring communism, then we deal with it without the help of anyone” was really a dramatic paradox. Movements of Turkism on 3rd of May did not curb the movement of Turkism, on the contrary, the transformation the government avoided most happened and supporters of Turk- ism spread to all parts of the country by politicizing. While Nihal Atsız, one of the nationalist leaders of the time- was summarizing results taken out from the trial process by his ideology, he could not even be regarded unjust in his remarks saying “The 3rd of May became a turning point in the history of Turkism. Turkism, which was only a thought and emotion and which could not go beyond literary and scientific borders, became a movement sud- denly on the 3rd of May, 1944”. Keywords: Turanism Movements, Turk nationalism, one-party ideology, Nihal Atsız, socialism, racism. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

The Uyghur Genocide

EARNING YOUR TRUST, EVERY DAY. 08.14.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 15 “AN INDUSTRY EXISTS BECAUSE THERE IS A MARKET FOR IT.” —THE GROWING SERMON-PREP INDUSTRY, P. 38 P. INDUSTRY, SERMON-PREP GROWING —THE IT.” FOR MARKET A IS THERE BECAUSE EXISTS INDUSTRY “AN THE UYGHUR GENOCIDE P.44 v36 15 COVER+TOC.indd 1 7/27/21 10:57 AM WHAT IS DONE FOR GOD’S GLORY WILL ENDURE FOREVER. RIGHT NOW COUNTS FOREVER LEARN HOW TO LIVE ALL OF LIFE IN LIGHT OF ETERNITY TODAY. LIGONIER.ORG/LEARN v36 15 COVER+TOC.indd 2 7/27/21 12:00 PM FEATURES 08.14.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 15 50 LIFE AND NEW LIFE Ultrasound technology is a powerful tool against the culture of death—but it has its limits by Leah Savas 38 44 58 SERMONS TO GO ERASING THE UYGHURS CHRONICLING THE PRO-LIFE Plagiarism controversies bring attention Testimonies and research at a United MOVEMENT to a question pastors face when Kingdom tribunal paint a harrowing WORLD’s coverage of the battle for the preparing material for the pulpit: picture of China’s intentions to assimilate unborn highlights the highs and lows of a How much borrowing is too much? the ethnic group by force movement with often unexpected allies by Jamie Dean by June Cheng by Leah Savas PHOTO BY LEE LOVE/GENESIS 08.14.21 WORLD v36 15 COVER+TOC.indd 1 7/28/21 8:47 AM DEPARTMENTS 08.14.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 15 5 MAILBAG 6 NOTES FROM THE CEO 65 Bowe Becker swims in the 4x100 freestyle relay final during the Tokyo Olympics. -

Developments

Highlights: Accountability: • Nearly three months after the International Court of Justice's ruling on the Rohingya genocide case, the Myanmar President has asked civil servants, military officials and the general people "not to commit genocide". Camp Conditions: • At least 15 Rohingya refugees have died after a boat capsized in the Bay of Bengal. • The Border Guard Bangladesh has intensified patrolling amid speculation of a fresh influx of Rohingyas from bordering Myanmar, as 150 Rohingya have appeared at the border. BGB has said they will not allow anyone to enter Bangladesh illegally. • Bangladesh has imposed a "complete lockdown" in Cox's Bazar district, including the Rohingya camps, to halt the spread of coronavirus. High-level Statements: • The independent human rights expert who monitors Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, has condemned the crackdown on the rights to freedom of expression and access to information that is related to ongoing armed conflict and risks undermining efforts to fight the COVID-19 pandemic in the country. International Support: • The UK has announced around £21 million to support Bangladesh’s efforts to fight the coronavirus outbreak and help preparedness in the Rohingya refugee camps. • Britain has said it is pledging 200 million pounds ($248 million) to the World Health Organisation (WHO) and charities to help slow the spread of the coronavirus in vulnerable countries and so help prevent a second wave of infections. Developments: ActionAid wants government action for proper relief distribution New Age Bangladesh (April 12) ActionAid Bangladesh has said the government should undertake initiatives around COVID-19 relief operation with the continuation of social distancing. -

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour Conductor and Guide: Norayr Daduryan

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour conductor and guide: Norayr Daduryan Price ~ $4,000 June 11, Thursday Departure. LAX flight to Armenia. June 12, Friday Arrival. Transport to hotel. June 13, Saturday 09:00 “Barev Yerevan” (Hello Yerevan): Walking tour- Republic Square, the fashionable Northern Avenue, Flower-man statue, Swan Lake, Opera House. 11:00 Statue of Hayk- The epic story of the birth of the Armenian nation 12:00 Garni temple. (77 A.D.) 14:00 Lunch at Sergey’s village house-restaurant. (included) 16:00 Geghard monastery complex and cave churches. (UNESCO World Heritage site.) June 14, Sunday 08:00-09:00 “Vernissage”: open-air market for antiques, Soviet-era artifacts, souvenirs, and more. th 11:00 Amberd castle on Mt. Aragats, 10 c. 13:00 “Armenian Letters” monument in Artashavan. 14:00 Hovhannavank monastery on the edge of Kasagh river gorge, (4th-13th cc.) Mr. Daduryan will retell the Biblical parable of the 10 virgins depicted on the church portal (1250 A.D.) 15:00 Van Ardi vineyard tour with a sunset dinner enjoying fine Italian food. (included) June 15, Monday 08:00 Tsaghkadzor mountain ski lift. th 12:00 Sevanavank monastery on Lake Sevan peninsula (9 century). Boat trip on Lake Sevan. (If weather permits.) 15:00 Lunch in Dilijan. Reimagined Armenian traditional food. (included) 16:00 Charming Dilijan town tour. 18:00 Haghartsin monastery, Dilijan. Mr. Daduryan will sing an acrostic hymn composed in the monastery in 1200’s. June 16, Tuesday 09:00 Equestrian statue of epic hero David of Sassoon. 09:30-11:30 Train- City of Gyumri- Orphanage visit. -

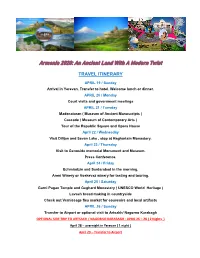

Armenia 2020: an Ancient Land with a Modern Twist

Armenia 2020: An Ancient Land With A Modern Twist TRAVEL ITINERARY APRIL 19 / Sunday Arrival in Yerevan. Transfer to hotel. Welcome lunch or dinner. APRIL 20 / Monday Court visits and government meetings APRIL 21 / Tuesday Madenataran ( Museum of Ancient Manuscripts ) Cascade ( Museum of Contemporary Arts ) Tour of the Republic Square and Opera House April 22 / Wednesday Visit Dilijan and Sevan Lake , stop at Haghartsin Monastery. April 23 / Thursday Visit to Genocide memorial Monument and Museum. Press Conference. April 24 / Friday Echmiadzin and Sardarabad in the morning. Areni Winery or Voskevaz winery for tasting and touring. April 25 / Saturday Garni Pagan Temple and Geghard Monastery ( UNESCO World Heritage ) Lavash bread making in countryside Check out Vernissage flea market for souvenirs and local artifacts APRIL 26 / Sunday Transfer to Airport or optional visit to Artsakh/ Nagorno Karabagh OPTIONAL SIDE TRIP TO ARTSAKH / NAGORNO KARABAGH : APRIL 26 – 28 ( 2 Nights ) April 28 – overnight in Yerevan ( 1 night ) April 29 – Transfer to Airport PRICES per person: Land Only! Double Occupancy Single Supplement MARRIOTT ( Deluxe room ) $1800 // $2300 MARRIOTT ( Superior ) $1900 // $2400 MARRIOTT ( Executive ) $2000 // $2650 ARTSAKH / NAGORNO-KARABAGH ( Optional side trip ) PRICE per person : HOTEL Double Occupancy Single Supplement VALLEX/ MARRIOTT ( Deluxe ) $400 // $100 VALLEX / MARRIOTT ( Superior ) $450 // $100 VALLEX / MARRIOTT ( Executive ) $500 // $100 EXTRA NIGHTS PER ROOM AT ARMENIA MARRIOTT DOUBLE SINGLE Deluxe $180 / $150 Superior $200 / $170 Executive $220 / $200 Included: Transfers , Half board meals ( daily breakfast & lunch, one dinner , one cultural event, English speaking guide on tour days and transportation as specified in itinerary. PAYMENT $500 non-refundable deposit due by November 30, 2019 by each participant. -

Kurds & the Conflict in Syria

Handout: Kurds & the Conflict in Syria TeachableMoment Handout – page 1 Background The Kurdish fight for a land of their own goes back centuries. The immediate roots of the current conflict date to 2011, when multiple forces in Syria rebelled against the autocratic rule of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. In 2012, Syrian Kurds (the country’s largest ethnic minority) formed their own small self-governed area in northern Syria. In 2014, at the same time as a bloody civil war was raging in Syria, the group ISIS began taking over territory in Iraq and Syria in its attempt to create a fundamentalist Islamic state. The Kurds joined the fight against ISIS and became an essential partner in the U.S.-led coalition battling ISIS. As the Kurds captured ISIS-held territory, suffering enormous casualties, they incorporated the area into their self-rule. Turkey is home to the largest population of Kurds in the world—about 12 million. The Kurdish minority has faced severe repression in Turkey, including the banning of the Kurdish language in speech, publishing, and even song. Even the words “Kurd” and “Kurdish” were banned. The fight for civil and political rights combined with a push for an independent state and erupted into an armed rebellion in the 1980s. The response from the Turkish state and military has been overwhelming and lethal. Tens of thousands of Kurds have been killed in a lopsided on-again off-again war. The self-governed Kurdish areas in Northern Syria came together in 2014 to form an autonomous region with a decentralized democratic government. -

Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 414 September 2019

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 414 SEPTEMBER 2019 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 414 September 2019 • TURKEY: DESPITE SOME ACQUITTALS, STILL MASS CONVICTIONS.... • TURKEY: MANY DEMONSTRATIONS AFTER FURTHER DISMISSALS OF HDP MAYORS • ROJAVA: TURKEY CONTINUES ITS THREATS • IRAQ: A CONSTITUTION FOR THE KURDISTAN REGION? • IRAN: HIGHLY CONTESTED, THE REGIME IS AGAIN STEPPING UP ITS REPRESSION TURKEY: DESPITE SOME ACQUITTALS, STILL MASS CONVICTIONS.... he Turkish govern- economist. The vice-president of ten points lower than the previ- ment is increasingly the CHP, Aykut Erdoğdu, ous year, with the disagreement embarrassed by the recalled that the Istanbul rate rising from 38 to 48%. On economic situation. Chamber of Commerce had esti- 16, TurkStat published unem- T The TurkStat Statistical mated annual inflation at ployment figures for June: 13%, Institute reported on 2 22.55%. The figure of the trade up 2.8%, or 4,253,000 unem- September that production in the union Türk-İş is almost identical. ployed. For young people aged previous quarter fell by 1.5% HDP MP Garo Paylan ironically 15 to 24, it is 24.8%, an increase compared to the same period in said: “Mr. -

III TURKISH STUDIES (Incl. Balkan) Medieterranean

NAGARA BOOKS ----------------------------------------- 231 -------------------------------------------------------------- -- 2825 Abulafia, David The Great Sea: a human history of the III TURKISH STUDIES (incl. Balkan) Medieterranean . xxxi,816p photos. maps Oxford/N.Y. 2013(11) 9780199315994 pap. 4,220 トルコ研究 Interweaving major political and naval developments with the ebb and flow of trade, Abulafia explores how commercial competition in the Mediterranean created both rivalries and partnerships, with merchants acting as 2819 intermediaries between cultures, trading goods that İbn Âbidîn were as exotic on one side of the sea as they were Hanefîlerde Mezhep Usûlü (Şerhu Ukûdi resmi'l- commonplace on the other. müftî) , inceleme-tercüme. ed. & tr. byŞenol Saylan 2826 342p (with Arabic text) Istanbul 2016 Acar, M. Şinasi 9786055245993 1,780 Osmanlı'dan Bugüne Gözümüzden Kaçanlar . 191p 2820 photos. illus. Istanbul 2013 9786054793037 6,660 İbrâhîm, Andurreşîd Curiosities and wonders -- Time -- Press -- Turkey -- Âlem-i İslâm ve Japonya'da İslâmiyetin Yayılması: History Türkistan, Sibirya, Moğolistan, Mançurya, Japonya, 2827 Kore, Çin, Singapur, Uzak Hind Adaları, Hindistan, Adalet, Begüm Arabistan, Dâru'l-hilafe . 2 vols. Istanbul 2012 Holtels and Highways: the construction of 9789753501347 4,620 modernization theory in cold war Turkey . (Stanford Abdürreşid İbrahîm, 1853-1944 -- Islam -- Japan -- Studies in Middle Eastern and Islamic Societies and Asia Cultures) 304p Stanford 2018 9781503605541 2821 pap 4,522 İnalcık, Halil Among the most critical tools in the U.S.'s ideological Has-Bağçede 'Ayş u Tarab: nedîmler şâîrler arsenal was modernization theory, and Turkey emerged mutrîbler . (Seçme Eserleri, III) xiii,496p ills. photos. as a vital test case for the construction and validation of Istanbul 2016(11) 9786053324171 1,940 developmental thought and practice. -

IPAC Q&A: Backbench Business Debate on Uyghur Genocide

Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China Q&A: Backbench Business debate on Uyghur Genocide Motion “That this House believes that Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region are suffering Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide.” And calls upon the Government to act to fulfil their obligations under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide and all relevant instruments of international law to bring it to an end. (Nusrat Ghani MP) Details Thursday 22nd April 2021, Chamber Context The publishing of two independent legal analyses has added to mounting evidence suggesting that the gross human rights abuses being perpetrated against the Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China (XUAR) constitute Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. What is the evidence that a Genocide is taking place against Uyghurs? Two major independent analyses have investigated reports of alleged genocide in the Xinjiang region: ● A formal legal opinion published by Essex Court Chambers in London, which concludes that there is a “very credible case” that the Chinese government is carrying out the crime of Genocide against the Uyghur people. ● A report from the Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy, conducted by over 30 independent global experts, which finds that the Chinese state is in breach of every act prohibited in Article II of the Genocide Convention. Both reports conclude there is sufficient evidence that the prohibited acts specified within the Genocide Convention and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court have been breached with respect to the Uyghurs, namely: 1. -

Turkish Journal of History

ISSN 1015-1818 | e-ISSN 2619-9505 2021 / 1 Sayı: 73 Tarih Dergisi Turkish Journal of History Tarih Kaynağı Olarak Seyahatler Journeys as a Source of History Kurucusu Ord. Prof. M. Cavid Baysun İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi yayınıdır Official Journal of Istanbul University Faculty of Letters Tarih Dergisi Turkish Journal of History ISSN 1015-1818 E-ISSN 2619-9505 Sayı/Issue 73, 2021/1 Tarih Dergisi Web of Science-Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM TR-Dizin, SCOPUS ve EBSCO Historical Abstracts tarafından indekslenmektedir. Turkish Journal of History is currently indexed by Web of Science-Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM TR-Dizin, SCOPUS and EBSCO Historical Abstracts. Kapak Resmi / Cover Photo Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Kütüphanesi, H. 2148, vr. 8a. Tarih Dergisi Turkish Journal of History ISSN 1015-1818 E-ISSN 2619-9505 Sayı/Issue 73, 2021/1 Sahibi / Owner İstanbul Üniversitesi / Istanbul University Yayın Sahibi Temsilcisi / Representative of Owner Prof. Dr. Hayati DEVELİ Istanbul Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, İstanbul Türkiye / Istanbul University, Faculty of Letters, Istanbul, Turkey Sorumlu Müdür / Responsible Manager Prof. Dr. Arzu TOZDUMAN TERZİ Istanbul Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, İstanbul Türkiye / Istanbul University, Faculty of Letters, Istanbul, Turkey Yazışma Adresi / Correspondence Address İstanbul Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, Tarih Bölümü Ordu Cad. No: 6, Laleli, Fatih 34459, İstanbul, Türkiye Telefon / Phone: +90 (212) 455 57 00 / 15882 E-mail: [email protected] https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/iutarih Yayıncı / Publisher İstanbul Üniversitesi Yayınevi / Istanbul University Press İstanbul Üniversitesi Merkez Kampüsü, 34452 Beyazıt, Fatih / İstanbul, Türkiye Telefon / Phone: +90 (212) 440 00 00 Baskı / Printed by İlbey Matbaa Kağıt Reklam Org.