The Polheim Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antarctic Treaty System And

The Antarctic Treaty System and Law During the first half of the 20th century a series of territorial claims were made to parts of Antarctica, including New Zealand's claim to the Ross Dependency in 1923. These claims created significant international political tension over Antarctica which was compounded by military activities in the region by several nations during the Second World War. These tensions were eased by the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957-58, the first substantial multi-national programme of scientific research in Antarctica. The IGY was pivotal not only in recognising the scientific value of Antarctica, but also in promoting co- operation among nations active in the region. The outstanding success of the IGY led to a series of negotiations to find a solution to the political disputes surrounding the continent. The outcome to these negotiations was the Antarctic Treaty. The Antarctic Treaty The Antarctic Treaty was signed in Washington on 1 December 1959 by the twelve nations that had been active during the IGY (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, United Kingdom, United States and USSR). It entered into force on 23 June 1961. The Treaty, which applies to all land and ice-shelves south of 60° South latitude, is remarkably short for an international agreement – just 14 articles long. The twelve nations that adopted the Treaty in 1959 recognised that "it is in the interests of all mankind that Antarctica shall continue forever to be used exclusively for peaceful purposes and shall not become the scene or object of international discord". -

Office of Polar Programs

DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SURFACE TRAVERSE CAPABILITIES IN ANTARCTICA COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION DRAFT (15 January 2004) FINAL (30 August 2004) National Science Foundation 4201 Wilson Boulevard Arlington, Virginia 22230 DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SURFACE TRAVERSE CAPABILITIES IN ANTARCTICA FINAL COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Purpose.......................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation (CEE) Process .......................................................1-1 1.3 Document Organization .............................................................................................................1-2 2.0 BACKGROUND OF SURFACE TRAVERSES IN ANTARCTICA..................................2-1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................2-1 2.2 Re-supply Traverses...................................................................................................................2-1 2.3 Scientific Traverses and Surface-Based Surveys .......................................................................2-5 3.0 ALTERNATIVES ....................................................................................................................3-1 -

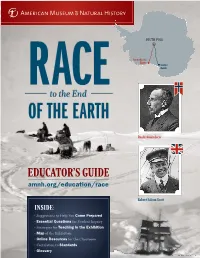

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

Asynchronous Antarctic and Greenland Ice-Volume Contributions to the Last Interglacial Sea-Level Highstand

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12874-3 OPEN Asynchronous Antarctic and Greenland ice-volume contributions to the last interglacial sea-level highstand Eelco J. Rohling 1,2,7*, Fiona D. Hibbert 1,7*, Katharine M. Grant1, Eirik V. Galaasen 3, Nil Irvalı 3, Helga F. Kleiven 3, Gianluca Marino1,4, Ulysses Ninnemann3, Andrew P. Roberts1, Yair Rosenthal5, Hartmut Schulz6, Felicity H. Williams 1 & Jimin Yu 1 1234567890():,; The last interglacial (LIG; ~130 to ~118 thousand years ago, ka) was the last time global sea level rose well above the present level. Greenland Ice Sheet (GrIS) contributions were insufficient to explain the highstand, so that substantial Antarctic Ice Sheet (AIS) reduction is implied. However, the nature and drivers of GrIS and AIS reductions remain enigmatic, even though they may be critical for understanding future sea-level rise. Here we complement existing records with new data, and reveal that the LIG contained an AIS-derived highstand from ~129.5 to ~125 ka, a lowstand centred on 125–124 ka, and joint AIS + GrIS contributions from ~123.5 to ~118 ka. Moreover, a dual substructure within the first highstand suggests temporal variability in the AIS contributions. Implied rates of sea-level rise are high (up to several meters per century; m c−1), and lend credibility to high rates inferred by ice modelling under certain ice-shelf instability parameterisations. 1 Research School of Earth Sciences, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. 2 Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton, National Oceanography Centre, Southampton SO14 3ZH, UK. 3 Department of Earth Science and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, University of Bergen, Allegaten 41, 5007 Bergen, Norway. -

Texts G7 Sout Pole Expeditions

READING CLOSELY GRADE 7 UNIT TEXTS AUTHOR DATE PUBLISHER L NOTES Text #1: Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen (Photo Collages) Scott Polar Research Inst., University of Cambridge - Two collages combine pictures of the British and the Norwegian Various NA NA National Library of Norway expeditions, to support examining and comparing visual details. - Norwegian Polar Institute Text #2: The Last Expedition, Ch. V (Explorers Journal) Robert Falcon Journal entry from 2/2/1911 presents Scott’s almost poetic 1913 Smith Elder 1160L Scott “impressions” early in his trip to the South Pole. Text #3: Roald Amundsen South Pole (Video) Viking River Combines images, maps, text and narration, to present a historical NA Viking River Cruises NA Cruises narrative about Amundsen and the Great Race to the South Pole. Text #4: Scott’s Hut & the Explorer’s Heritage of Antarctica (Website) UNESCO World Google Cultural Website allows students to do a virtual tour of Scott’s Antarctic hut NA NA Wonders Project Institute and its surrounding landscape, and links to other resources. Text #5: To Build a Fire (Short Story) The Century Excerpt from the famous short story describes a man’s desperate Jack London 1908 920L Magazine attempts to build a saving =re after plunging into frigid water. Text #6: The North Pole, Ch. XXI (Historical Narrative) Narrative from the =rst man to reach the North Pole describes the Robert Peary 1910 Frederick A. Stokes 1380L dangers and challenges of Arctic exploration. Text #7: The South Pole, Ch. XII (Historical Narrative) Roald Narrative recounts the days leading up to Amundsen’s triumphant 1912 John Murray 1070L Amundsen arrival at the Pole on 12/14/1911 – and winning the Great Race. -

Polartrec Teacher Joins Hunt for Old Ice in Antarctica

NEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL ICE CORE LABORATORY — SCIENCE MANAGEMENT OFFICE Vol. 5 Issue 1 • SPRING 2010 PolarTREC Teacher Joins Hunt for Old Eric Cravens: Ice in Antarctica Farewell & By Jacquelyn (Jackie) Hams, PolarTREC Teacher Thanks! Courtesy: PolarTREC ... page 2 WAIS Divide Ice Core Images Now Available from AGDC ... page 3 WAIS Divide Ice Dave Marchant and Jackie Hams Core Update Photo: PolarTREC ... page 3 WHEN I APPLIED to the PolarTREC I actually left for Antarctica. I was originally program (http://www.polartrec.com/), I was selected by the CReSIS (Center for Remote asked where I would prefer to go given the Sensing of Ice Sheets) project, which has options of the Arctic, Antarctica, or either. I headquarters at the University of Kansas. I checked the Antarctica box only, despite the met and spent a few days visiting the team at Drilling for Old Ice fact that I may have decreased my chances of the University of Kansas and had dinner at the being selected. Antarctica was my preference Principal Investigator’s home with other team ... page 5 for many reasons. As a teacher I felt that members. We were all pleased with the match Antarctica represented the last frontier to study and looked forward to working together. the geologic history of the planet because the continent is uninhabited, not polluted, and In the late summer of 2008, I was informed that NEEM Reaches restricted to pure research. Over the last few the project was cancelled and that I would be Eemian and years I have noticed that my students were assigned to another research team. -

The South Polar Race Medal

The South Polar Race Medal Created by Danuta Solowiej The way to the South Pole / Sydpolen. Roald Amundsen’s track is in Red and Captain Scott’s track is in Green. The South Polar Race Medal Roald Amundsen and his team reaching the Sydpolen on 14 Desember 1911. (Obverse) Captain R. F. Scott, RN and his team reaching the South Pole on 17 January 1912. (Reverse) Created by Danuta Solowiej Published by Sim Comfort Associates 29 March 2012 Background The 100th anniversary of man’s first attainment of the South Pole recalls a story of two iron-willed explorers committed to their final race for the ultimate prize, which resulted in both triumph and tragedy. In July 1895, the International Geographical Congress met in Lon- don and opened Antarctica’s portal by deciding that the southern- most continent would become the primary focus of new explora- tion. Indeed, Antarctica is the only such land mass in our world where man has ventured and not found man. Up until that time, no one had explored the hinterland of the frozen continent, and even the vast majority of its coastline was still unknown. The meet- ing touched off a flurry of activity, and soon thereafter national expeditions and private ventures started organizing: the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration had begun, and the attainment of the South Pole became the pinnacle of that age. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (1872-1928) nurtured at an early age a strong desire to be an explorer in his snowy Norwegian surroundings, and later sailed on an Arctic sealing voyage. -

S. Antarctic Projects Officer Bullet

S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER BULLET VOLUME III NUMBER 8 APRIL 1962 Instructions given by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty ti James Clark Ross, Esquire, Captain of HMS EREBUS, 14 September 1839, in J. C. Ross, A Voya ge of Dis- covery_and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions, . I, pp. xxiv-xxv: In the following summer, your provisions having been completed and your crews refreshed, you will proceed direct to the southward, in order to determine the position of the magnet- ic pole, and oven to attain to it if pssble, which it is hoped will be one of the remarka- ble and creditable results of this expedition. In the execution, however, of this arduous part of the service entrusted to your enter- prise and to your resources, you are to use your best endoavours to withdraw from the high latitudes in time to prevent the ships being besot with the ice Volume III, No. 8 April 1962 CONTENTS South Magnetic Pole 1 University of Miohigan Glaoiologioal Work on the Ross Ice Shelf, 1961-62 9 by Charles W. M. Swithinbank 2 Little America - Byrd Traverse, by Major Wilbur E. Martin, USA 6 Air Development Squadron SIX, Navy Unit Commendation 16 Geological Reoonnaissanoe of the Ellsworth Mountains, by Paul G. Schmidt 17 Hydrographio Offices Shipboard Marine Geophysical Program, by Alan Ballard and James Q. Tierney 21 Sentinel flange Mapped 23 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 24 The Bulletin is pleased to present four firsthand accounts of activities in the Antarctic during the recent season. The Illustration accompanying Major Martins log is an official U.S. -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Representations of Antarctic Exploration by Lesser Known Heroic Era Photographers

Filtering ‘ways of seeing’ through their lenses: representations of Antarctic exploration by lesser known Heroic Era photographers. Patricia Margaret Millar B.A. (1972), B.Ed. (Hons) (1999), Ph.D. (Ed.) (2005), B.Ant.Stud. (Hons) (2009) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science – Social Sciences. University of Tasmania 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date ii Abstract Photographers made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known photographers were the professionals, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of photographs were also taken on Belgian, German, Swedish, French, Norwegian and Japanese expeditions. These were taken by amateurs, sometimes designated official photographers, often scientists recording their research. Apart from a few Pole-reaching images from the Norwegian expedition, these lesser known expedition photographers and their work seldom feature in the scholarly literature on the Heroic Era, but they, too, have their importance. They played a vital role in the growing understanding and advancement of Antarctic science; they provided visual evidence of their nation’s determination to penetrate the polar unknown; and they played a formative role in public perceptions of Antarctic geopolitics. -

Joint Conference of the History EG and Humanities and Social Sciences

Joint conference of the History EG and Humanities and Social Sciences EG "Antarctic Wilderness: Perspectives from History, the Humanities and the Social Sciences" Colorado State University, Fort Collins (USA), 20 - 23 May 2015 A joint conference of the History Expert Group and the Humanities and Social Sciences Expert Group on "Antarctic Wilderness: Perspectives from History, the Humanities and the Social Sciences" was held at Colorado State University in Fort Collins (USA) on 20-23 May 2015. On Wednesday (20 May) we started with an excursion to the Rocky Mountain National Park close to Estes. A hike of two hours took us along a former golf course that had been remodelled as a natural plain, and served as a fitting site for a discussion with park staff on “comparative wilderness” given the different connotations of that term in isolated Antarctica and comparatively accessible Colorado. After our return to Fort Collins we met a group of members of APECS (Association of Polar Early Career Scientists), with whom we had a tour through the New Belgium Brewery. The evening concluded with a screening of the film “Nightfall on Gaia” by the anthropologist Juan Francisco Salazar (Australia), which provides an insight into current social interactions on King George Island and connections to the natural and political complexities of the sixth continent. The conference itself was opened by on Thursday (21 May) by Diana Wall, head of the School of Global Environmental Sustainability at the Colorado State University (CSU). Andres Zarankin (Brazil) opened the first session on narratives and counter narratives from Antarctica with his talk on sealers, marginality, and official narratives in Antarctic history. -

Leadership Lessons from Sir Douglas Mawson

LEADERSHIP LESSONS FROM SIR DOUGLAS MAWSON Sir Douglas Mawson was one of the most courageous and adventurous men Australia has produced. Through his determination and efforts he added to the Commonwealth an area in Antarctica almost as large as Australia itself. He was born in Yorkshire, England May 1882 and at the age of four his parents migrated to Sydney. He was educated at the University of Sydney and played a leading role in founding the Science Society. His great interest was geology and in 1902 he joined expeditions to survey the land around Mittagong and later the New Hebrides Islands. In 1905 he was appointed Lecturer in Mineralogy and Petrology at the University of Adelaide which he served in various capacities until his death. In 1907 a tour of the Snowy Mountains became his first experience of a glacial environment with an ascent of Mount Kosciusko and the beginning of his interest in Antarctica. At this time Britain, Germany and Sweden were involved in Antarctica, Ernest Shackleton was determined to reach the South Pole and in 1907 lead a party with Mawson joining as physicist and surveyor of the expedition. They reached the continent in February 1908 and Shackleton decided that Mawson, Professor Edgeworth David and Dr Forbes MacKay should travel 1800km to the Magnetic Pole. During the expedition they met very bad surfaces and some blizzards and they had underestimated the distance to the Magnetic Pole. While they reached their destination all were in poor condition with only seal meat to eat. They struggled back over hundreds of kilometres of ice caps and at last saw their ship, the Nimrod, less than a kilometre away when suddenly Mawson fell six metres down a crevasse.