National Register of Historic Places Hydroeiectirc Projects Continuation Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Cascades Contested Terrain

North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History CONTESTED TERRAIN: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History By David Louter 1998 National Park Service Seattle, Washington TABLE OF CONTENTS adhi/index.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-1999 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/[11/22/2013 1:57:33 PM] North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History (Table of Contents) NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Cover: The Southern Pickett Range, 1963. (Courtesy of North Cascades National Park) Introduction Part I A Wilderness Park (1890s to 1968) Chapter 1 Contested Terrain: The Establishment of North Cascades National Park Part II The Making of a New Park (1968 to 1978) Chapter 2 Administration Chapter 3 Visitor Use and Development Chapter 4 Concessions Chapter 5 Wilderness Proposals and Backcountry Management Chapter 6 Research and Resource Management Chapter 7 Dam Dilemma: North Cascades National Park and the High Ross Dam Controversy Chapter 8 Stehekin: Land of Freedom and Want Part III The Wilderness Park Ideal and the Challenge of Traditional Park Management (1978 to 1998) Chapter 9 Administration Chapter 10 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/contents.htm[11/22/2013 -

OFR 2019–1144: Preliminary Assessment of Shallow Groundwater Chemistry Near Goodell Creek, North Cascades National Park, Washi

Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Preliminary Assessment of Shallow Groundwater Chemistry near Goodell Creek, North Cascades National Park, Washington Open-File Report 2019–1144 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Preliminary Assessment of Shallow Groundwater Chemistry near Goodell Creek, North Cascades National Park, Washington By Rich W. Sheibley and James R. Foreman Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Open-File Report 2019–1144 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Sheibley, R.W., and Foreman, J.R., 2019, Preliminary assessment of shallow groundwater chemistry near Goodell Creek, North Cascades National Park, Washington: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2019–1144, 14 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20191144. -

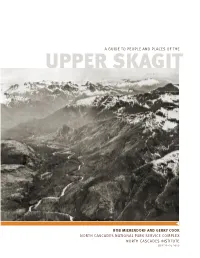

Upper Skagit

A GUIDE TO PEOPLE AND PLACES OF THE UPPER SKAGIT BOB MIERENDORF AND GERRY COOK NORTH CASCADES NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COMPLEX NORTH CASCADES INSTITUTE JULY 22–25 2010 1 CLASS FIELD DAYS ITINERARY PEOPLE AND PLACES OF THE UPPER SKAGIT RIVER JULY 22–25, 2010 FRIDAY 9 am Drive from ELC to Ross Dam Trailhead parking lot 9:15–10:00 Hike to Ross Lake (end of haul road) – Brief stop on trail at a Ross Dam overlook – Load ourselves and gear on the Mule 10:30 am Welcome to the Wild Upper Skagit – Rules of the Mule and other safety matters – Instructor and participant introductions Noon Lunch on the Mule near Big Beaver Creek 2:45 pm Second stop near May Creek (no rest rooms here) 6 pm Arrive at Lightning Horse Camp (our base camp for two nights) 7 pm Potluck dinner SATURDAY 7 am Breakfast 8 am–Noon Ethnobotany hike along Eastbank Trail – About a two mile hike, rolling terrain – Gerry will pick us up with the Mule – Lunch on the Mule 1 pm Quick rest room stop at Boundary Bay Campground 3 pm Arrive at International Boundary 3:15 pm Stop at Winnebago Flats – There are toilets here – Get drinking water and fill water jugs 3:45 pm Depart Winnebago Flats on return trip 5 pm Arrive back at our camp 6:30 pm Potluck dinner SUNDAY ABOUT THE COVER 7 am Breakfast U.S. Forest Service, Mt. Baker 8 am Break camp and load Mule Ranger District, 1931 oblique 9 am Depart on Mule aerial facing 182o (south), of pre-impoundment Skagit River 10 am Arrive at Big Beaver Campground flood plain; Skymo Creek canyon – There are rest rooms here in lower right, Devil’s Creek canyon – Hike up Big Beaver to old growth cedar grove emerging from middle left. -

National Register of Historic Places Hydroeiectirc Projects Continuation Sheet

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-O018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service skagit ^VQT & Newhalem Creek National Register of Historic Places Hydroeiectirc Projects Continuation Sheet Section number ___ Page ___ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 96000416 Date Listed: 4/26/96 Skagit River & Newhalem Creek Hvdroelectirc Projects Whatcom WA Property Name County State Hydroelectric Power Plant MPS Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. Signature of tty^Keejifer Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Photographs: The SHPO has verified that the 1989 photographs accurately document the current condition and integrity of the nominated resources. Historic Photos #1-26 are provided as photocopy duplications. Resource Count: The resource count is revised to read: Contributing Noncontributing 21 6 buildings 2 - sites 5 6 structures 1 - objects 29 12 total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register 16 . A revised inventory list is appended to clarify the resource count and contributing status of properties in the district, particularly at the powerplant/dam sites. (See attached) This information was confirmed with Lauren McCroskey of the WA SHPO. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Skagit River & Newhalem Creek National Register of Historic Places Hydroelectirc Projects Continuation Sheet Section number The following is a list of the contributing and noncontributing resources within the district, beginning at its westernmost—downstream—end, organized according to geographic location. -

Youth Heritage Project

YOUTH HERITAGE PROJECT 2018 FINAL REPORT PARTNERS A huge thanks to our program partners for their significant financial and programmatic support for this year’s Youth Heritage Project! for the intrusion of the facilities within the Park. Students were able to witness a firsthand example NORTH CASCADES of this: all participants stayed at the North Cascades Institute’s Environmental Learning Center, which was constructed through mitigation funding as part NATIONAL PARK of a previous relicensing process. The relicensing process is once again being initiated. To take advantage of this real-world application, we The Washington Trust for Historic Preservation Within NOCA there is an active hydroelectric asked students to propose potential mitigation for held our seventh annual Discover Washington: project–a fairly unusual feature for a National Park. continuing operation of the hydroelectric project. Youth Heritage Project (YHP) this year at North These three dams, constructed from 1919-1960 prior We spent the first two days of YHP providing students Cascades National Park (NOCA). YHP continues to to establishment of the Park, still provide about with background information to aid their proposals, fulfill a long-standing goal of the Washington Trust 20% of Seattle’s electricity. Operation of the dams introducing students to both natural and historic to provide proactive outreach to and education for continues through a licensing agreement between resources within the Park. Students learned about young people. YHP is designed to introduce historic Seattle City Light and the Federal Energy Regulatory the establishment of the hydroelectric project and preservation to the younger generation, because in Commission. Periodically, Seattle City Light must the ongoing development of the Skagit River in the this next generation are the future leaders who will go through a relicensing process to continue twentieth century. -

The Damnation of a Dam : the High Ross Dam Controversy

THE DAMYIATION OF A DAM: TIIE HIGH ROSS DAM CONTROVERSY TERRY ALLAN SIblMONS A. B., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1968 A THESIS SUBIUTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY May 1974 All rights reserved. This thesis may not b? reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Terry Allan Simmons Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Damnation of a Dam: The High Ross Dam Controversy Examining Committee: Chairman: F. F. Cunningham 4 E.. Gibson Seni Supervisor / /( L. J. Evendon / I. K. Fox ernal Examiner Professor School of Community and Regional Planning University of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University rhe righc to lcnd my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed ' without my written permission. Title of' ~hesis /mqqmkm: The Damnation nf a nam. ~m -Author: / " (signature ) Terrv A. S.imrnonze (name ) July 22, 1974 (date) ABSTRACT In 1967, after nearly fifty years of preparation, inter- national negotiations concerning the construction of the High Ross Dan1 on the Skagit River were concluded between the Province of British Columbia and the City of Seattle. -

Ross Lake National Recreation Area Within North Q Baker Lake Cascades National Park Service Complex

' »* » « L i r * ' IwJ^I WM Mt. Shuksan of North Cascades National Park and Mt. Baker of Mt. Baker Snoqualmie National Forest Welcome to National Park and National Forest lands of the North Cascades. Recreational Located east of 1-5, there are many opportunities for you to enjoy this area with easy access Opportunities from several major highways. Start in the north and take a drive on the Mt. Baker Scenic Byway page 2 (State Route 542). This route begins in Bellingham, winds along the North Fork of the Nooksack River, and, from the town of Glacier, climbs 24 miles to an elevation of 5,100 feet at Artist Point in Heather Meadows. This destination is legendary for spectacular views of Mt. Baker, Mt. Shuksan and surrounding peaks. For other stunning vistas, follow the northern part of the Cascade Loop along the North Cascades Scenic Highway (State Route 20). A side trip up the Baker Lake Road, 16 miles east of Sedro-Woolley, leads into the Baker Lake Basin, which features campgrounds, water recreation, and numerous trails. Trip Planning and Safety page 3 The 125-mile Skagit Wild and Scenic River System - made up of segments of the Skagit, Cascade, Sauk, and Suiattle rivers - provides important wildlife habitat and recreation. The Skagit River is home to one of the largest winter populations of bald eagles in the United States and provides spawning grounds for one-third of all salmon in Puget Sound. The North Cascades Scenic Highway winds east £ through the gateway communities of Concrete, D Rockport, and Marblemount before reaching Ross Lake National Recreation Area within North Q Baker Lake Cascades National Park Service Complex. -

North Cascades National Park I Mcallister Cutthroat Pass A

To Hope, B.C. S ka 40mi 64km gi t R iv er Chilliwack S il Lake v e CHILLIWACK LAKE SKAGIT VALLEY r MANNING - S k a g PROVINCIAL PARK PROVINCIAL PARK i PROVINCIAL PARK t Ross Lake R o a d British Columbia CANADA Washington Hozomeen UNITED STATES S i Hozomeen Mountain le Silver Mount Winthrop s Sil Hoz 8066ft ia ve o Castle Peak 7850ft Lake r m 2459m Cr 8306ft 2393m ee e k e 2532m MOUNT BAKER WILDERNESS Little Jackass n C Mount Spickard re Mountain T B 8979ft r e l e a k i ar R 4387ft Hozomeen Castle Pass 2737m i a e d l r C ou 1337m T r b Lake e t G e k Mount Redoubt lacie 4-wheel-drive k r W c 8969ft conditions east Jack i Ridley Lake Twin a l of this point 2734m P lo w er Point i ry w k Lakes l Joker Mountain e l L re i C ak 7603ft n h e l r C R Tra ee i C i Copper Mountain a e re O l Willow 2317m t r v e le n 7142ft T i R k t F a e S k s o w R Lake a 2177m In d S e r u e o C k h g d e u c r Goat Mountain d i b u i a Hopkins t C h 6890ft R k n c Skagit Peak Pass C 2100m a C rail Desolation Peak w r r T 6800ft li Cre e ave 6102ft er il ek e e Be 2073m 542 p h k Littl 1860m p C o Noo R C ks i n a Silver Fir v k latio k ck c e ee Deso e Ro Cree k r Cr k k l e il e i r B e N a r Trail a C To Glacier r r O T r C Thre O u s T e Fool B (U.S. -

North Cascades National Park Plan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Business Management Group North Cascades National Park 2012 Business Plan Produced by Sunrise at Copper Lookout. National Park Service Business Management Group Table of Contents U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Spring 2012 2 INTRODUCTION National Park Business Plan Process 2 Letter from the Superintendent 3 Introduction to North Cascades National Park The purpose of business planning in the National Park Service (NPS) is to improve the ability of parks to more clearly 4 PARK OVERVIEW communicate their financial and operational status to principal 4 Orientation stakeholders. A business plan answers such questions as: What 5 Mission and Foundation is the business of this park unit? What are its priorities over 6 Resources the next five years? How will the park allocate its resources to 7 Visitor Information achieve these goals? 8 Personnel 9 Volunteers The business planning process is undertaken to accomplish three 10 Partnerships main tasks. First, it presents a clear, detailed picture of the state 12 Strategic Goals of park operations and priorities. Second, it outlines the park’s 14 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW financial projections and specific strategies the park may employ to marshal additional resources to apply toward its operational 14 Funding Sources and Expenditures needs. Finally, it provides the park with a synopsis of its funding 15 Division Allocations sources and expenditures. 16 DIVISION OVERVIEWS 16 Facility Management 18 Resource Management -

Fingertip Facts

FINGERTIP FACTS To Bothell MISSION SERVICE AREA Substation Seattle City Light is dedicated to delivering customers affordable, AND reliable and environmentally responsible electricity services. SUBSTATIONS Shoreline VISION We resolve to provide a positive, fulfilling and engaging experience for our employees. We will expect and reinforce Viewland-Hoffman leadership behaviors that contribute to that culture. Our workforce is the foundation upon which we achieve our public service goals North and will reflect the diversity of the community we serve. We strive to improve quality of life by understanding and Canal answering the needs of our customers. We aim to provide University more opportunities to those with fewer resources and will Lake Washington protect the well-being and safety of the public. Denny Broad We aspire to be the nation’s greenest utility by fulfilling our Puget East Pine mission in an environmentally and socially responsible manner. Sound Union VALUES Massachusetts SAFETY – The safety of our employees and customers is our highest priority South ENVIRONMENTAL STEWARDSHIP – We will enhance, protect Delridge and preserve the environment in which we operate Substations INNOVATION – We will be forward-focused and seek new, Seattle City Limits innovative solutions to meet the challenges of tomorrow Duwamish EXCELLENCE – We strive for fiscal responsibility and Creston-Nelson excellence in employee accountability, trust and diversity CUSTOMER CARE – We will always promote the interest of our customers and serve them reliably, ethically, transparently and with integrity 1 SEATTLE CITY LIGHT | FINGERTIP FACTS FINGERTIP FACTS | SEATTLE CITY LIGHT 2 GENERAL INFORMATION CUSTOMER STATISTICS The most current data available for the year ended December 31, 2018. -

Naturally Appealing: a Scenic Gateway in Washington's North

Naturally Appealing A scenic getaway in Washington’s North Cascades | By Scott Driscoll s o u r h i k i n g g r o u p arrives at the top of Heather Park, about 110 miles northeast of Seattle. Pass in Washington state’s North Cascades, The Park Service is celebrating the park’s we hear several low, guttural grunts. 40th birthday this year, and also the 20th anni- “That’s the sound of my heart after versary of the Washing- ton Park Wilderness seeing a bear,” comments a female hiker. She Act, which designated 94 percent of the park chuckles a trifle nervously, and we all look around. as wilderness. This area’s “majestic Those grunts sound like they’re coming from more mountain scenery, snowfields, glaciers, than one large animal. alpine meadows, lakes and other unique glaci- Whatever’s causing the sound remains well hid- ated features” were cited den behind huckleberries, subalpine firs and boul- as some of the reasons ders, but Libby Mills, our naturalist guide, sets our Congress chose to pro- minds at ease. “Those tect the land in 1968 are male dusky grouse,” “for the benefit, use and she assures us. “They’re inspiration of present competing for female and future generations.” attention.” Those natural fea- She explains that they tures are also among the make the grunting reasons the Park Service sound by inhaling air posted this quote—from CAROLYN WATERS into pink sacs—one at 19th century Scottish each side of the neck— botanist David Douglas, one of the early explorers of and then releasing the the Pacific Northwest and the person for whom the air. -

Newhalem Area Day Hikes Information

North Cascades National Park 2105 Highway 20 Ross Lake National Recreation Area Sedro Woolley Lake Chelan National Recreation Area Washington 98284 Newhalem Area Day Hikes Information Welcome Many hours can be spent exploring trails in the Newhalem vicinity. From valley paths to accessible boardwalks, there is variety and reward for everyone. Be well prepared, have current information. Do you have proper shoes, clothes, first aid kit, extra water, food, map, flashlight? Be sure a responsible person knows your route and schedule. Enjoy the North Cascades! Sterling Munro Trail Trailhead is just outside the northwest corner of the North Cas (1) cades Visitor Center. This 330 foot boardwalk trail offers excellent views of the Picket Range up the Goodell Creek drainage. Wheel chair accessible. Newhalem Creek This .4 mile access trail connects the North Cascades Visitor Campground/ Center to loops A & B in Newhalem Creek Campground, the Amphitheater Trail (2) amphitheater and trails: including the River Loop and "To Know a Tree" nature trails. The 1 mile loop west of Newhalem Creek Campground River Loop Trail (3) leads through a variety of forest growth to a peaceful river bar with sweeping views. Caution is advised near the Skagit River since it is extremely swift and cold. "To Know a Tree" Accessible from points near the Newhalem Creek Campground Nature Trail (4) entrance station and amphitheater. Mostly level, .5 miles, with packed gravel surface. Skirts the campground, follows the river, wanders among large trees, and lush understory growth. Find plaques interpreting common trees and plants along the way. Lower Newhalem Starts .3 miles along the service road past Newhalem Campground loops Creek Trail (5) C and D, 40 yards beyondthe steel grated Newhalem Creek Bridge.