ED181502.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

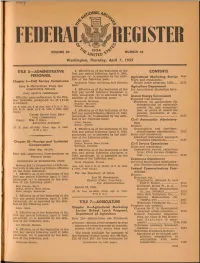

Ederal Register

EDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 20 7S*. 1934 NUMBER 68 ' ^NlTtO •* Washington, Thursday, April 7 , 7955 TITLE 5— ADMINISTRATIVE 5. Effective as of the beginning of the CONTENTS first pay period following April 9, 1955, PERSONNEL paragraph (a) is amended by the addi Agricultural Marketing Service Pa&e tion of the following post: Chapter I— Civil Service Commission Rules and regulations: Artibonite Valley (including Bois Dehors), School lunch program, 1955__ 2185 H aiti. P art 6— E x c eptio n s P rom t h e Agriculture Department C o m petitiv e S ervice 6. Effective as of the beginning of the See Agricultural Marketing Serv C iv il. SERVICE COMMISSION first pay period following December 4, ice. 1954, paragraph (b) is amended by the Atomic Energy Commission Effective upon publication in the F ed addition of the following posts: Proposed rule making: eral R egister, paragraph (c) of § 6.145 Boudenib, Morocco. Procedure on applications for is revoked. Guercif, Morocco. determination of reasonable (R. S. 1753, sec. 2, 22 S tat. 403; 5 U. S. C. 631, Tiznit, Morocco. royalty fee, Just compensa 633; E. O. 10440, 18 P. R. 1823, 3 CFR, 1953 7. Effective as of the beginning of the tion, or grant of award for Supp.) first pay period following March 12,1955, patents, inventions or dis U n ited S tates C iv il S erv- paragraph (b) is amended by the addi coveries__________________ 2193 vice C o m m issio n , tion of the following posts: [seal] W m . C. H u l l , Civil Aeronautics Administra Executive Assistant. -

STATE of MINNESOTA DISTRICT COURT HENNEPIN COUNTY FOURTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT State of Minnesota Plaintiff, the Honorable Peter A

27-CR-20-12646 Filed in District Court State of Minnesota 8/4/2021 3:13 PM STATE OF MINNESOTA DISTRICT COURT HENNEPIN COUNTY FOURTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT State of Minnesota Plaintiff, The Honorable Peter A. Cahill vs. Derek Michael Chauvin Dist. Ct. File 27-CR-20-12646 Defendant MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MEDIA COALITION’S MOTION TO UNSEAL JUROR IDENTITIES AND OTHER JUROR MATERIALS American Public Media Group (which owns Minnesota Public Radio); The Associated Press; Cable News Network, Inc.; CBS Broadcasting Inc. (on behalf of WCCO-TV and CBS News); Court TV Media LLC; Dow Jones & Company (which publishes The Wall Street Journal); Fox/UTV Holdings, LLC (which owns KMSP-TV); Gannett Satellite Information Network, LLC (which publishes USA Today); Hubbard Broadcasting, Inc. (on behalf of its broadcast stations, KSTP-TV, WDIO-DT, KAAL, KOB, WNYT, WHEC-TV, and WTOP-FM); Minnesota Coalition on Government Information; NBCUniversal Media, LLC; The New York Times Company; The Silha Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law; Star Tribune Media Company LLC; TEGNA Inc. (which owns KARE-TV); and WP Company LLC (which publishes The Washington Post) (collectively, the “Media Coalition”) by and through undersigned counsel, hereby submit this Motion to Unseal Juror Identities and Other Juror Materials. 27-CR-20-12646 Filed in District Court State of Minnesota 8/4/2021 3:13 PM INTRODUCTION This is not a motion that the Media Coalition brings lightly or, for that matter, quickly. It has waited through trial, through verdict, through sentencing, and until now—more than three months after the jurors completed their service in the trial of Derek Chauvin—out of respect for the integrity of the proceedings, for the Court’s articulated concerns about juror impartiality and safety, and for the jurors themselves, who served their community under very difficult circumstances and handled harrowing evidence and testimony. -

Ccfiber TV Channel Lineup

CCFiber TV Channel Lineup Locals+ Expanded (cont'd) Stingray Music Premium Channels (cont'd) 2 WKRN (ABC) 134 Travel Channel Included within Ultimate Cinemax Package 4 WSMV (NBC) 140 Viceland 210 Adult Alternative 5 WTVF (CBS) 144 OWN 211 ALT Rock Classics 330 5StarMAX 6 WTVF 5+ 145 Oxygen 212 Americana 331 ActionMAX East 8 WNPT (PBS) 146 Bravo 213 Bluegrass 332 ActionMAX West 9 QVC 147 E! 214 Broadway 333 MaxLatino 10 QVC2 148 We TV 215 Chamber Music 334 Cinemax East 12 ION 149 Lifetime 216 Classic Masters 335 Cinemax West 14 Qubo 151 Lifetime Movie Network 217 Classic R&B Soul 336 MoreMAX East 17 WZTV (FOX) 153 Hallmark Channel 218 Classic Rock 337 MoreMAX West 19 EWTN 154 Hallmark Movie 219 Country Classics 338 MovieMAX 20 Shop HQ 155 Hallmark Drama 220 Dance Clubbin 339 OuterMAX 21 Inspiration 160 Nick Jr. 221 Easy Listening 340 ThrillerMAX East 22 TBN 161 Disney Channel 222 Eclectic Electronic 341 ThrillerMAX West 25 WPGD 164 Cartoon Network 223 Everything 80's 27 CSPAN 165 Discovery Family 224 Flashback 70's Starz Package 28 CSPAN 2 166 Universal Kids 225 Folk Roots 29 CSPAN 3 168 Nickelodeon 226 Gospel 360 Starz West 30 WNPX (ION) 189 TV Land 227 Groove Disco and Funk 361 Starz East 32 WUXP (MY TV) 190 MTV 228 Heavy Metal 362 Starz Kids East 35 Jewelry TV 191 MTV 2 229 Hip Hop 363 Starz Kids West 36 HSN 192 VH1 230 Hit List 364 Starz in Black West 37 HSN2 194 BET 231 Holiday Hits 365 Starz in Black East 38 WJFB (Shopping) 200 CMT 232 Hot Country 366 Starz Edge West 41 WHTN (CTN) Ultimate (Includes Locals+ & Expanded) 233 Jammin -

Annex 12 Models for Nations and Regions PSB Television

Ofcom Public Service Broadcasting Review Models for Nations and Regions PSB Television: A Focus on Scotland An Overview by Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates Ltd September 2008 DISCLAIMER This report has been produced by Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates Limited (“O&O”) for Ofcom as part of the ongoing Review of Public Service Broadcasting (the “PSB Review”, ”the Project”). While the information provided herein is believed to be accurate, O&O makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of such information. The information contained herein was prepared expressly for use herein and is based on certain assumptions and information available at the time this report was prepared. There is no representation, warranty or other assurance that any of the projections or estimates will be realised, and nothing contained within this report is or should be relied upon as a promise or representation as to the future. In furnishing this report, O&O reserves the right to amend or replace the report at any time and undertakes no obligation to provide the users with access to any additional information. O&O’s principal task has been to collect, analyse and present data on the market and its prospects under a number of potential scenarios. O&O has not been asked to verify the accuracy of the information it has received from whatever source. Although O&O has been asked to express its opinion on the market and business prospects, it has never been the users’ intention that O&O should be held legally liable for its judgements in this regard. -

Providence Magazine June 1924 Millions Hear

PROVIDENCE MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY THE PROVIDENCE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE Vol . XXXV . JUNE , 1924 No. 6 . Millions Hear from Providence Daily Our Radio Service Covers Land and Sea Brings Joy and Comfort to Many Homes OWEVER well known Providence has been in former President of the United States as he discusses subjects of na years on account of its great and world - leading manufac tional importance ; that of some great prelate , some orator of tures , and its sterling products that have enjoyed a universal prominence ; some distinguished educator , or the foreign diplo distribution , it has become more extensively known in the last mat who is the guest of honor at a state banquet . two years than ever before . This may seem like a paradox , but Only a few weeks ago , Providence received the greetings the truth is that through the development of that wonderful of many cities , from Havana , and Florida centres to the South ; invention — the radio — there are many in the United States , and San Francisco to the West , and a score of others in the Western up in Canada , who erstwhile knew little or nothing at all of States , as they were brought into Chicago by the American Providence ; whereas , to - day , Providence , figuratively speaking , Telephone and Telegraph Company , over about five thousand is not only knocking at their doors , day after day , but it enters miles of land wire and approximately 200 miles of ocean cables , their homes and is made a most welcome guest . and were relayed here , again to be sent out to thousands of Providence is one of the greatest broadcasting cities in the homes . -

Cutest Trick of the Week

2 Monday, October 3, 1949 RADIO DAILY * COMING AND GOING Vol. 49, No. 1 Monday, Oct. 3, 1949 10 Cts. MORGAN BEATTY, whose "News of the HOWARD S. MEIGHAN, Columbia netwo World" is heard on NBC, will return today vice -president and general executive, who ha JOHN W. ALICOATE Publisher from England, where he made a study of the been named CBS chief executive officer on the situation resulting from the devaluation of West Coast, has arrived in Hollywood to tak over his new duties. FRANK BURKE Editor the pound. MARVIN KIRSCH : Business Manager KEN SPARNON, field representative for TED GRANIK, whose "American Radio BMI, left over the week -end for Memphis, Forum" debuts as a simulcast on NBC tele where he'll attend the meeting of District 6, and AM on Sunday, October 30, has returned Published daily except Saturdays. Sundays NAB. From there he'll go to Chattanooga on from Kansas City, where he flew for con- and Holidays at 1501 Broadway, New York, business, and later will attend the meeting ferences with a prospective sponsor. (18). N. Y., by Radio Daily Corp., J. W. of NAB's District 4 at Pinchurst, N. C. Alicoate, President.and Publisher; Donald M GEORGE B. STORER, JR., manager of Mersereau, Treasurer and General Manager; LEE LITTLE, president of KTUC, Columbia WAGA -TV, the Fort Industry TV station in Marvin Kirsch, Vice- President; Chester B. network outlet in Tucson, Ariz., a visitor Atlanta, Ga., who attended the color tele- Bahn, Vice -President; Charles A. AlicoLte, Friday at the New York headquarters of the vision hearings at the FCC last week, is ex- Secretary. -

Licensing Division for the Correct Form

This form is effective beginning with the January 1 to June 30, 2017 accounting period (2017/1) SA3E If you are filing for a prior accounting period, contact the Licensing Division for the correct form. Long Form Return completed workbook by STATEMENT OF ACCOUNT FOR COPYRIGHT OFFICE USE ONLY email to: for Secondary Transmissions by DATE RECEIVED AMOUNT Cable Systems (Long Form) [email protected] $ General instructions are located in 01/25/2021 ALLOCATION NUMBER For additional information, the first tab of this workbook. contact the U.S. Copyright Office Licensing Division at: Tel: (202) 707-8150 A ACCOUNTING PERIOD COVERED BY THIS STATEMENT: Accounting 2020/2 Period Instructions: B Give the full legal name of the owner of the cable system. If the owner is a subsidiary of another corporation, give the full corpo- Owner rate title of the subsidiary, not that of the parent corporation. List any other name or names under which the owner conducts the business of the cable system. If there were different owners during the accounting period, only the owner on the last day of the accounting period should submit a single statement of account and royalty fee payment covering the entire accounting period. Check here if this is the system’s first filing. If not, enter the system’s ID number assigned by the Licensing Division. 061974 LEGAL NAME OF OWNER/MAILING ADDRESS OF CABLE SYSTEM North Central Communications, Inc. 06197420202 061974 2020/2 P.O. Box 70 Lafayette, TN 37083 INSTRUCTIONS: In line 1, give any business or trade names used to identify the business and operation of the system unless these C names already appear in space B. -

Lhadeasting the BUSINESS WEEKLY of TELEVISION and RADIO

MVNUJI J. I.IYJ ..e....IU lhadeaSting THE BUSINESS WEEKLY OF TELEVISION AND RADIO FCC reports TV revenue at $1.8 billion for `64. p27 Did killing option time weaken stations? p36 Two -year study sees dark future for pay TV. p46 ew production problems expected in big switch to color. p54 COMPLETE INDEX PAGE 7 Radio spreads the word fastest The millions who commute by car rely on Radio traffic reports to get them to the job on time. Spot Radio routes them to your product in markets where your sales need a boost. T I+ OfiIG AL S'AION f1E>AESENTATIvE NEW YORK CHICAGO ATLANTA BOSTON DALLAS DETROIT LOS ANGELES PHILADELPHIA SAN FRANCISCO ST. LOUIS HERE'S PROLOG I... it separates you from AM and puts you in FM automatically! two tape transports provide 12 hours of music without repeating any selection, and you can alternate from tape to tape at any time interval desired single cartridge and up to 48 rotating cartridge units can be scheduled to play at any time interval desired can be expanded into major Prolog System for unattended programming and logging for brochure on Prolog Type 1002 System, write Commercial Sales, Continental Electronics Mfg. Co., Box 17040, Dallas, Texas 75217 and request Prolog I LT V Co- Ltix,LLaL A DIVISION OF L ING- TEMCO -VO UG Fi T, INC. not the biggest dome in town... but the best television station KTRKTV 1:Di HOUSTON BROADCASTING, August 9, 1965 3 This fall, NBC nighttime programs 96% in color. All 28- carried by WGALTV. -

DOCUNENT AESUME Shively, Joe E.; and Others .A Television Survey

DOCUNENT AESUME ED 127 024 95 PS 008 733 AUTHOR Shively, Joe E.; And Others TITLE .A Television Survey of Appalachian Pdrents of Preschool Children. INSTITUTION Appalachia Bducatipnal Lab., Charleston,W. Va. SPONS AGENCY Iiational Inst. ofstduration (DHEW),Washington, D.C. REPORT. NO AEL-TR-47 PUB DATE Jan 75 CONTRACT . OEC-3-7-062909-3070 NOTE 40p.; Pages 36 thiough 42 of the original doCument are copyrighted and therefore not available. They are not included in the pagination. For related documents, see PS 008 6,61 and PS 008 731-737 EDRS PRICE BE-$0.83 HC-$2.06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cable Television.; Color Television; Commercial Television; *Early Childhood Education; Educational Television;. *Home Programs; Interdention;Measurement Techniques; Parents; Preschool Children;Program Planning; Questionnaires; Radio; *RuralFamily; *Television Surveys; *Television Viewing; Viewing Time IDENTIFIERS Alabama,; *Appalachia; *Home Oriented Preschgol Education Program (HOPE);. Kentucky; Earketable- , Preschool Education Program (MPEP); Ohio; PennsylVenia; Tennessee; Virginia; West Virginia ABSTRACT A total of 699 Appalachian families with 'preschool children were surveyed to gather informationon the availability and use of television, radio-and telephone in their hones. Thesurvey was designed to assess the practicality of usingtelevision as one of the compon&its of th'e Marketable Preschool Education(MPE) Program, an extension of the Appalachia Educational Laboratory'sHome-Oriented Preschool Education (HOPE) Program. Survey items'abouttelevision included questions about availability',presence of color capability, size of set, reception of stations, number ofnon7functioning sets, and quality of reception, as wellas viewing habits and prefetelices of children. Availability of telephone,and radiowere also surveyed. Results were'presented in detailed data tables. -

Review – ) MB Docket No

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the matter of ) ) 2018 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – ) MB Docket No. 18-349 Review of the Commission’s Broadcast ) Ownership Rules and Other Rules Adopted ) Pursuant to Section 202 of the ) Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) REPLY COMMENTS OF TEGNA INC. Akin S. Harrison Senior Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary Michael Beder Associate General Counsel TEGNA Inc. 8350 Broad Street, Suite 2000 Tysons, VA 22102 May 29, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... iii I. COMPETITION IN THE BROADER VIDEO MARKET – NOT ARTIFICIAL BROADCAST-FOCUSED RESTRAINTS – DRIVES INVESTMENT IN LOCAL SERVICE ....................................................................................................................................... 3 A. Competition for Advertising is Intense and Growing. ................................................... 4 B. Intermodal Competition Drives Broadcaster Investment in Local Content. ............... 6 C. Common Ownership Enables Stations to Offer More Local Content .......................... 9 II. CALLS TO MAINTAIN OR INCREASE BROADCAST TV OWNERSHIP RESTRICTIONS RELY ON DISTORTED VIEWS OF MARKET DYNAMICS .............. 12 CONCLUSION .......................................................................................................................... -

Federal Communications Commission DA 03-1780 Before The

Federal Communications Commission DA 03-1780 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of: ) ) Christian Television Network, Inc. ) ) CSR-6095-M v. ) ) Tele-Media Company of Southwest Kentucky ) ) Tele-Media of Franklin ) ) Request for Mandatory Carriage of ) Television Station WHTN-TV, Murfreesboro, Tennessee MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: May 23, 2003 Released: May 28, 2003 By the Deputy Chief, Policy Division, Media Bureau: I. INTRODUCTION 1. Christian Television Network, Inc. (“Christian TV”), licensee of television broadcast station WHTN-TV, Murfreesboro, Tennessee (“WHTN” or the “Station”) filed the above-captioned must carry complaint against Tele-Media Company of Southwest Kentucky and Tele-Media of Franklin (“Tele- Media”), for failing to carry WHTN on its cable television systems serving the Nashville, Tennessee DMA, specifically Adairville, Allen County, Auburn, incorporated Franklin, unincorporated Franklin, Lewisburg, incorporated Russellville, unincorporated Russellville, and Scottsville, Kentucky (the “cable communities”). Tele-Media filed an opposition to which Christian TV replied. For the reasons discussed below, we grant the complaint for must carry status in the cable communities. II. BACKGROUND 2. Under Section 614 of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended, and implementing rules adopted by the Commission in Implementation of the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, Broadcast Signal Carriage Issues (“Must Carry Order”), commercial television broadcast stations such as WJAL are entitled to assert mandatory carriage rights on cable systems located within the station’s market.1 A station’s market for this purpose is its “designated market area,” or DMA, as defined by Nielsen Media Research.2 The term DMA is a geographic market designation that defines each television market exclusive of others, based on measured viewing patterns. -

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1961-1962

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1961-1962 Eastern Kentucky University Year 1961 Eastern Progress - 27 Oct 1961 Eastern Kentucky University This paper is posted at Encompass. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress 1961-62/6 WELCOME DOWN THE ALUMNI! H1LLTOPPERS! ■ oozess ' ■ "Keeping Pace In A Progressive Era" Friday, October 27, 1961 Student Publication of Eastern Kentucky State College, Richmond, Kentucky Vol.39, No. 6 Alumni Reunion To 33 Eastern College Seniors Begin Homecoming • Homecoming: festivities 'at Eastern began last night and will continue through tonio'row evening In what ia expected to^bc the biggest alumni reuiuon ami most colorful homecoming In Eastern's 66- year History. The annual homecoming dance, to be held tonight from 8 until midnight in Walnut Hall of the'Keen Johnson Student Union Building, wi|l kick off the 1961 celebiution for the alumni. Twenty-six candi- Who dates for homecoming queen will be presented at this time. The majority of the alumni will Military Day at Eastern, will he n.-vmed for the vice chairman of Thirty-three of Eastern's senior* report to the campus early tomor- among the other marching units , the board of regents, and Me- have been selected •> 1 htp row morning for a full day's pro- that wilt include Hov Scout groups. Gregor Hall, a six-story women's In "Who's Who Amon- Students in gramming. Registration of alumni thoroughbred riding group, and dormitory to house 448. was named Ameiican Colleges :I-I Un ver- and friends is vet for tomorrow others. for Judge Thomas B. McGregor.' sifies." This is considered the most from 9 a.