Lessons from Enron Thomas G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telecommunications Provider Locator

Telecommunications Provider Locator Industry Analysis & Technology Division Wireline Competition Bureau March 2009 This report is available for reference in the FCC’s Information Center at 445 12th Street, S.W., Courtyard Level. Copies may be purchased by contacting Best Copy and Printing, Inc., Portals II, 445 12th Street S.W., Room CY-B402, Washington, D.C. 20554, telephone 800-378-3160, facsimile 202-488-5563, or via e-mail at [email protected]. This report can be downloaded and interactively searched on the Wireline Competition Bureau Statistical Reports Internet site located at www.fcc.gov/wcb/iatd/locator.html. Telecommunications Provider Locator This report lists the contact information, primary telecommunications business and service(s) offered by 6,252 telecommunications providers. The last report was released September 7, 2007.1 The information in this report is drawn from providers’ Telecommunications Reporting Worksheets (FCC Form 499-A). It can be used by customers to identify and locate telecommunications providers, by telecommunications providers to identify and locate others in the industry, and by equipment vendors to identify potential customers. Virtually all providers of telecommunications must file FCC Form 499-A each year.2 These forms are not filed with the FCC but rather with the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), which serves as the data collection agent. The pool of filers contained in this edition consists of companies that operated and collected revenue during 2006, as well as new companies that file the form to fulfill the Commission’s registration requirement.3 Information from filings received by USAC after October 16, 2007, and from filings that were incomplete has been excluded from this report. -

THE HISTORY of ONLINE SEARCHING by Matt Hannigan

AT A LONG STRANGE TRIP IT'S BEEN: THE HISTORY OF ONLINE SEARCHING by Matt Hannigan, lndianapolis-Mmion Cotm[Y Public Library N THE BEGINNING You can't miss the timeline that runs through this article. What I find remarkable is how fast all of this When the editor asked me to write this stuff occurred. I sometimes feel like one of those history of the last twenty years of cartoon characters who is left standing in his union suit searching it wasn't because I'm the senior statesperson after being whirled about in the dust of the Road of online in Indiana. That title rightly belongs to Ann Runner or Speedy Gonzalez. Van Camp (formerly of the IU Medical Library, now an independent searcher). Nor am I the intellectual When I first started my career in libraries back in backbone of Indiana's online community. That honor 1978, a young scholar would drive to the library, find a goes to Becki Whitaker of the Indiana Cooperative parking space, locate the proper division, find a Library Services Authority (INCOLSA) . Becki is online's periodical index, guess at a subject and finally identify nearest approximation to Star Trek's Mr. Speck. My and locate an article on the history of the Punic War. role has been more like that of Forrest Gump or Jar Jar These days the same young student jumps out of bed, Binks - I just happened to be along for the ride. Arid logs onto the Net, types some keywords into an EBSCO what a ride it has been! One can picture future Carl database - and in a few moments is reading an article Sagans and Jacob Bronowskis speaking of this era and on the history of MTV. -

Liquid Assets: Enron's Dip Into Water Business Highlights Pitfalls of Privatization

Liquid Assets: Enron's Dip into Water Business Highlights Pitfalls of Privatization A special report by Public Citizen’s Critical Mass Energy and Environment Program Washington, D.C. March 2002 Liquid Assets: Enron's Dip into Water Business Highlights Pitfalls of Privatization A special report by Public Citizen’s Critical Mass Energy and Environment Program Washington, D.C. March 2002 This document can be viewed or downloaded at www.citizen.org/cmep. Public Citizen 215 Pennsylvania Ave., S.E. Washington, D.C. 20003 202-546-4996 fax: 202-547-7392 [email protected] www.citizen.org/cmep © 2002 Public Citizen. All rights reserved. Public Citizen, founded by Ralph Nader in 1971, is a non-profit research, lobbying and litigation organization based in Washington, D.C. Public Citizen advocates for consumer protection and for government and corporate accountability, and is supported by over 150,000 members throughout the United States. Liquid Assets: Enron's Dip into Water Business Highlights Pitfalls of Privatization Executive Summary The story of Enron Corp.’s failed venture into the water business serves as a cautionary tale for consumers and policymakers about the dangers of turning publicly operated water systems and resources over to private corporations and creating a private “market” system in which water can be traded as a commodity, as Enron did with electricity and tried to do with water. Enron’s water investments, which contributed to the company’s spectacular collapse, would not have been permitted had the Public Utility Holding Company Act (PUHCA) been properly enforced and not continually weakened by the deregulation initiatives advocated by Enron and other energy companies. -

SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q (Mark One) (X) QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarter ended October 31, 2000 ( ) TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File Number 000-23262 CMGI, INC. ---------- (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 04-2921333 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 100 Brickstone Square 01810 Andover, Massachusetts (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) (978) 684-3600 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes X No _____ ----- Number of shares outstanding of the issuer's common stock, as of December 11, 2000 Common Stock, par value $.01 per share 319,311,017 --------------------------------------- ----------- Class Number of shares outstanding CMGI, INC. FORM 10-Q INDEX Page Number ----------- Part I. FINANCIAL INFORMATION Item 1. Consolidated Financial Statements Consolidated Balance Sheets October 31, 2000 (unaudited) and July 31, 2000 3 Consolidated Statements of Operations Three months ended October 31, 2000 and 1999 (unaudited) 4 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows Three months ended October 31, 2000 and 1999 (unaudited) 5 Notes to Interim Unaudited Consolidated Financial Statements 6-13 Item 2. -

Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C. 20549

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 ----------------------- FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): November 17, 2000 CMGI, Inc. ----------------------------------------------------- (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 000-23262 04-2921333 -------------------------------------------------------------- (State or other juris- (Commission (IRS Employer diction of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 100 Brickstone Square, Andover, MA 01810 ---------------------------------------- --------- (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (978) 684-3600 N/A ------------------------------------------------------------- (Former name or former address, if changed since last report) Item 9. Regulation FD Disclosure ------------------------ On November 13, 2000 we conducted a conference call related to our financial guidance for the fiscal year ending July 31, 2001. We are furnishing the following information in response to questions received after the conference call. We do not intend to update this information, unless we believe that it is necessary to do so in accordance with Regulation FD. Q: What were CMGI's holdings of publicly traded stock at October 31, 2000? A: Please see Table 1. ------- Q: What were CMGI's holdings of publicly traded stock at July 31, 2000? A: Please see Table 2. ------- Q: Can you help us understand how/why CMGI's stock holdings are designated as "available-for-sale" in its consolidated balance sheet and why these stock holdings are "carved out" from the total pool of public securities held by the company? A: The classification of certain of our publicly traded stock holdings as "available-for-sale securities" in our consolidated balance sheet is governed by Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. -

Collapse of the Enron Corporation

S. HRG. 107–1141 COLLAPSE OF THE ENRON CORPORATION HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FEBRUARY 26, 2002 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 88–896 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 03-FEB-2003 08:49 Sep 29, 2005 Jkt 088896 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 D:\DOCS\88896.TXT SSC1 PsN: SSC1 COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JOHN McCAIN, Arizona, Ranking Republican JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts CONRAD BURNS, Montana JOHN B. BREAUX, Louisiana TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RON WYDEN, Oregon OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MAX CLELAND, Georgia SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas BARBARA BOXER, California GORDON SMITH, Oregon JOHN EDWARDS, North Carolina PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois JEAN CARNAHAN, Missouri JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada BILL NELSON, Florida GEORGE ALLEN, Virginia KEVIN D. KAYES, Democratic Staff Director MOSES BOYD, Democratic Chief Counsel JEANNE BUMPUS, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel (II) VerDate 03-FEB-2003 08:49 Sep 29, 2005 Jkt 088896 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 D:\DOCS\88896.TXT SSC1 PsN: SSC1 CONTENTS Page Hearing held on February 26, 2002 ...................................................................... -

(Nordic Journal of Documentation). This Paper Does Not Include the Final Publisher Journal Pagination

This is an author produced version of a paper published in Tidskrift för Dokumentation (Nordic Journal of Documentation). This paper does not include the final publisher journal pagination. Citation for the published paper: Våge, L., "Search engines of today and beyond", Tidskrift för Dokumentation, 2002, volume 57, issue 3, pp. 79-85. Published with permission from: Svensk förening för Informationsspecialister Search engines of today and beyond L. VÅGE Mid Sweden University Abstract The major Internet search engines nowadays makes it possible to search for keywords in vast quantities of web pages. In this article the most important crawler- based search engines are reviewed along with newer ones which are starting to make an impact. Web directories, meta- search engines and the use of sponsored links are considered as well as the future of web searching. The need for faster reindexing of the databases of search engines for the purpose of giving the users a more up-to-date view of the web is emphasized. Keywords Search engines, information retrieval. Searching for information using search engines is the second most popular activity among the users of the Internet. For some it might seem that there is an abundance of search engines to choose from but that picture has become increasingly untrue as we approach the end of the second year of the new millenium. In this article I will attempt to review the most important of the few that currently dominates Internet searching, with emphasis on crawler-based search engines which probably can be said to be the most comprehensive tools at the disposal of the web searcher. -

NARRATIVES of the ENRON SCANDAL in 2000S POLITICAL CULTURE

BIG BUSINESS, DEMOCRACY, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: NARRATIVES OF THE ENRON SCANDAL IN 2000s POLITICAL CULTURE Rosalie Genova A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Dr. John Kasson Dr. Michael Hunt Dr. Peter Coclanis Dr. Lawrence Grossberg Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse © 2010 Rosalie Genova ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ROSALIE GENOVA: Big Business, Democracy, and the American Way: Narratives of The Enron Scandal in 2000s Political Culture (Under the Direction of Dr. John Kasson) This study examines narratives of the Enron bankruptcy and their political, cultural and legal ramifications. People’s understandings and renderings of Enron have affected American politics and culture much more than have the company’s actual errors, blunders and lies. Accordingly, this analysis argues that narratives about Enron were, are, and will continue to be more important than any associated “facts.” Central themes of analysis include the legitimacy and accountability of leadership (both governmental and in business); contestation over who does or does not “understand” business, economics, or the law, and the implications thereof; and conceptions of the American way, the American dream, and American civic culture. The study also demonstrates how Enron narratives fit in to longer patterns of American commentary on big business. iii Dedicated to the memory of my father Paul, 1954-2008 the only “Doctor Genova” I have ever known iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To a certain extent, the colleagues who have been making fun of me ever since I developed my dissertation topic are right: this research process has been different, shall we say, from that of most historians. -

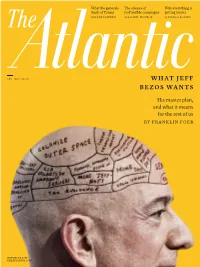

WHAT JEFF BEZOS WANTS JEFF BEZOS’S MASTER PLAN His Master Plan, and What It Means for the Rest of Us by FRANKLIN FOER the END of SILENCE

What the generals The science of Why everything is think of Trump GoFundMe campaigns getting louder by MARK BOWDEN by RACHEL MONROE by BIANCA BOSKER THE TECH ISSUE WHAT JEFF BEZOS WANTS JEFF BEZOS’S MASTER PLAN PLAN MASTER BEZOS’S JEFF His master plan, and what it means for the rest of us BY FRANKLIN FOER THE END OF SILENCE OF END THE NOVEMBER THEATLANTIC.COM NOVEMBER NOVEMBER THEATLANTIC.COM 1119_Cover [Print]_12456747.indd 1 9/18/2019 2:55:08 PM HILAREE NELSON FIRST EVER SKI DESCENT OF LHOTSE DEFY THE PAST WEAR THE FUTURE TO VIRTUALLY JOIN THE CLIMBERS ON THEIR JOURNEY TO CONQUER LHOTSE, SCAN THIS CODE OR VISIT: THEATLANTIC.COM/THENORTHFACE PHOTO: KALISZ 19080016_3_TNF_FL_THE_ATLANTIC_SPREAD_v2.indd All Pages 9/4/19 4:14 PM HILAREE NELSON FIRST EVER SKI DESCENT OF LHOTSE DEFY THE PAST WEAR THE FUTURE TO VIRTUALLY JOIN THE CLIMBERS ON THEIR JOURNEY TO CONQUER LHOTSE, SCAN THIS CODE OR VISIT: THEATLANTIC.COM/THENORTHFACE PHOTO: KALISZ 19080016_3_TNF_FL_THE_ATLANTIC_SPREAD_v2.indd All Pages 9/4/19 4:14 PM This content was created by Atlantic Re:think, the branded content studio at The Atlantic, and SPONSOR CONTENT SPONSOR CONTENT made possible by HPE. It does not necessarily reflect the views of The Atlantic’s editorial staff. the court, the backboards, and even the eyeing that vintage jersey for a few months balls, which can provide instant insights and just need a discount offer to pull and analytics. It means outfitting players the trigger, or even if your kid is playing with sensors that monitor real-time health a video game on his tablet that relates to data. -

The Future of Reading Sponsored By

The Future of Reading Sponsored By Amazon's Jeff Bezos already built a better bookstore. Now he believes he can improve upon one of humankind's most divine creations: the book itself. By Steven Levy NEWSWEEK Updated: 12:53 PM ET Nov 17, 2007 "Technology," computer pioneer Alan Kay once said, "is anything that was invented after you were born." So it's not surprising, when making mental lists of the most whiz-bangy technological creations in our lives, that we may overlook an object that is superbly designed, wickedly functional, infinitely useful and beloved more passionately than any gadget in a Best Buy: the book. It is a more reliable storage device than a hard disk drive, and it sports a killer user interface. (No instruction manual or "For Dummies" guide needed.) And, it is instant-on and requires no batteries. Many people think it is so perfect an invention that it can't be improved upon, and react with indignation at any implication to the contrary. "The book," says Jeff Bezos, 43, the CEO of Internet commerce giant Amazon.com, "just turns out to be an incredible device." Then he uncorks one of his trademark laughs. Books have been very good to Jeff Bezos. When he sought to make his mark in the nascent days of the Web, he chose to open an online store for books, a decision that led to billionaire status for him, dotcom glory for his company and countless hours wasted by authors checking their Amazon sales ratings. But as much as Bezos loves books professionally and personally—he's a big reader, and his wife is a novelist—he also understands that the surge of technology will engulf all media. -

The Posted Cure Amounts

Vendor Name+ Type II Vendor Contact Name Vendor Contact Address Lehman Entity The contracts highlighted in yellow below are being assumed by Purchaser pursuant to the Asset Purchase Agreement. Cure amounts are listed on Exhibit A by vendor. Two Chatham Center Access Data Corp. Access Data Corp. 24th FL Pittsburgh, PA 15219 LBHI 110 Parkway Dr. South Dimension Data Dimension Data Hauppauge, Ny 11788 LBI 3760 14th Avenue Platform Computing, Inc. Platform Computing, Inc. Markham Ontario Attn: General Counsel L3R 3T7 LBI Red Hat, Inc. 1801 Varsity Drive Red Hat, Inc. Attn: General Counsel Raleigh, NC 27606 LBI @STAKE, INC Master Agreement Ray Scutari, Royal Hansen, Emily Sebert 2 Wall Street, New York, NY 10005 Lehman Brothers, Inc. 1010 DATA, INC Trial N/A 65 Broadway, Suite 1010, New York, NY 10006 Lehman Brothers Holdings 2 TRACK GLOBAL Master Agreement N/A 1270 Broadway, Suite 208, New York, NY 10001 Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. 2 TRACK GLOBAL Amendment / Addendum / Schedule N/A 1270 Broadway, Suite 208, New York, NY 10001 Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. 2 TRACK GLOBAL Amendment / Addendum / Schedule N/A 1270 Broadway, Suite 208, New York, NY 10001 Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. 2 TRACK GLOBAL Transaction Schedule N/A 1270 Broadway, Suite 208, New York, NY 10001 Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. 2 TRACK GLOBAL Transaction Schedule N/A 1270 Broadway, Suite 208, New York, NY 10001 Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. 2 TRACK GLOBAL Transaction Schedule N/A 1270 Broadway, Suite 208, New York, NY 10001 Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. 2 TRACK GLOBAL Transaction Schedule N/A 1270 Broadway, Suite 208, New York, NY 10001 Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.