Project Background and Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MILL RUINS PARK RESEARCH STUDY Expansion of The

MILL RUINS PARK RESEARCH STUDY Expansion of the Waterpower Canal (1885) and Rebuilding of Tailrace Canals (1887-1892) Prepared for Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board 3800 Bryant Avenue South Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409-1029 Prepared by Hess, Roise and Company, Historical Consultants Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D., Principal Investigator Penny A. Petersen Nathan Weaver Olson The Foster House, 100 North First Street, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 With curriculum program by Dawn Peterson Ann Ericson May 2003 Expansion of the Waterpower Canal (1885) and Rebuilding of Tailrace Canals (1887-1892) The Construction of the Expanded Waterpower Canal and Rebuilding of the Tailrace Canals By the mid-1880s, the increasing number of mills and the demand for waterpower was jeopardizing the availability of that power, particularly as the height and flow of the Mississippi fluctuated from season to season. In 1883, the Minneapolis Mill Company hired William de la Barre as an engineer and agent for the waterpower works. A number of the mills had installed auxiliary steam engines to supplement the waterpower. Meanwhile De la Barre proposed to solve the waterpower problem by increasing the head and fall available. Working on the West Side canal (Minnesota Historical Society) According to Kane, “De la Barre undertook to deepen the canal and lower the tailraces under his jurisdiction, while the millers promised to lower their wheel pits, tailraces, and headraces. Before the year ended, De la Barre had deepened the canal from 14 to 20 feet and lengthened it from 600 to 950 feet. The expansion increased its flowage capacity from 30 to 40 per cent and raised the water level to produce more power by bring water to the lessees’ wheels at a greater head. -

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Statewide Report for Senator Stabenow 2020 Nov

Statewide Report for Senator Stabenow 2020 Nov. 1, 2019 - Oct. 31, 2020 799 660 183,798 $1,427,888 $1,158,700 Events Projects Participants Support Community Match Program and Grant Outreach H.O.P.E. Grants 116 grants KEWEENAW $661,085 in support HOUGHTON ONTONAGON BARAGA Humanities Grants GOGEBIC LUCE MARQUETTE ALGER CHIPPEWA IRON SCHOOLCRAFT 29 grants MACKINAC DICKINSON DELTA $376,207 in support MENOMINEE EMMET CHEBOYGAN PRESQUE ISLE Great Michigan Read CHARLEVOIX MONT- ALPENA (FY 2019/2020) ANTRIM OTSEGO MORENCY LEELANAU OSCODA ALCONA BENZIE GRAND KALKASKA CRAWFORD 298 non-profits participated PROGRAMS AND GRANTS TRAVERSE MISSAUKEE ROSCOMMON IOSCO Action Grants MANISTEE WEXFORD OGEMAW $216,050 in support Arts & Humanities Touring Grants ARENAC MASON LAKE OSCEOLA CLARE GLADWIN HURON Bridging Michigan* BAY Poetry Out Loud Great Michigan Read OCEANA MECOSTA ISABELLA MIDLAND NEWAYGO TUSCOLA SANILAC H.O.P.E. Grants SAGINAW students participated MONTCALM GRATIOT 5,077 MUSKEGON Humanities Grants GENESEE LAPEER ST. CLAIR KENT Museum on Main Street OTTAWA IONIA CLINTON SHIAWASSEE 44 schools MACOMB Poetry Out Loud OAKLAND INGHAM LIVINGSTON ALLEGAN BARRY EATON $88,000 in support Prime Time Family Reading Time® WASHTENAW WAYNE VAN BUREN KALAMAZOO CALHOUN JACKSON Arts/Touring Grants MONROE BERRIEN CASS ST. JOSEPH HILLSDALE LENAWEE * Bridging Michigan 2020 is a virtual program BRANCH 79 grants/communities $40,564 in support Michigan Humanities 2364 Woodlake Drive, Suite 100 Okemos, MI 48864 p: 517-372-7770 michiganhumanities.org | #MIHumanities FY2020 -

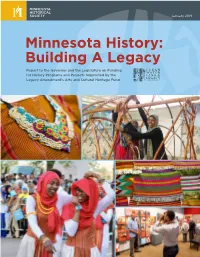

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund January 2011 Table of Contents Letter from the Minnesota Historical Society Director . 1 Overview . 2 Feature Stories on Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF) History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Initiatives Inspiring Students and Teachers . 6 Investing in People and Communities . 10 Dakota and Ojibwe: Preserving a Legacy . .12 Linking Past, Present and Future . .15 Access For Everyone . .18 ACHF History Appropriations Language . .21 Full Report of ACHF History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Statewide Initiatives Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants (Organized by Legislative District) . 23 Statewide Historic Programs . 75 Statewide History Partnership Projects . 83 “Our Minnesota” Exhibit . .91 Survey of Historical and Archaeological Sites . 92 Minnesota Digital Library . 93 Estimated cost of preparing and printing this report (as required by Minn. Stat. § 3.197): $18,400 Upon request the 2011 report will be made available in alternate format such as Braille, large print or audio tape. For TTY contact Minnesota Relay Service at 800-627-3529 and ask for the Minnesota Historical Society. For more information or for paper copies of the 2011 report contact the Society at: 345 Kellogg Blvd W., St Paul, MN 55102, 651-259-3000. The 2011 report is available at the Society’s website: www.mnhs.org/legacy. COVER IMAGES, CLOCKWIse FROM upper-LEFT: Teacher training field trip to Oliver H. -

The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: an Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 1 1976 The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J. Sheran Timothy J. Baland Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Sheran, Robert J. and Baland, Timothy J. (1976) "The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Sheran and Baland: The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An THE LAW, COURTS, AND LAWYERS IN THE FRONTIER DAYS OF MINNESOTA: AN INFORMAL LEGAL HISTORY OF THE YEARS 1835 TO 1865* By ROBERT J. SHERANt Chief Justice, Minnesota Supreme Court and Timothy J. Balandtt In this article Chief Justice Sheran and Mr. Baland trace the early history of the legal system in Minnesota. The formative years of the Minnesota court system and the individuals and events which shaped them are discussed with an eye towards the lasting contributionswhich they made to the system of today in this, our Bicentennialyear. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ^

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) r — ,, (Expires 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ^ This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in Hovi.to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entenhcfthe information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Pence Automobile Company Building other names/site number Minneapolis Gas Light Company; Builder's Building; Lincoln Office, Northwestern National Bank; Gamble-Skogmo; Carmichael-Lynch 2. Location street & number 800 Hennepin Avenue N/A not for publication city or town Minneapolis vicinity state Minnesota code MN county Hennepin code 053 zip code 55403-1803 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ^ meets Q does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

The Secrets of Egypt & the Nile

the secrets of egypt & the nile 2021 - 2022 Dear Valued Guest, Egypt has captured the world’s imagination and continues to make an extraordinary impression on those who visit; and beginning in September 2021, we are delighted to take you there. While traveling along Egypt’s Nile River, you’ll be treated to a connoisseur’s discovery of this ancient civilization as only AmaWaterways can provide—with an unparalleled river cruise and land adventure that includes exquisite cuisine, beautiful accommodations, authentic excursions and extraordinary service. Your journey along the world’s longest river on board our spectacular, newly designed AmaDahlia will take you to some of Egypt’s most iconic sites. Discover ancient splendors such as the Great Hypostyle Hall of Karnak, the beguiling Temple of Luxor and the mystifying Valley of the Kings and Queens, along with exclusive access to the Tomb of Queen Nefertari. While in Cairo, you’ll stay at the 5-star Four Seasons at The First Residence, an oasis in the middle of the city, where each day, you’ll experience some of the world’s most astonishing antiquities. Come face to face with King Tut’s priceless discoveries at the Egyptian Museum, as well as the Great Sphinx and the three Pyramids of Giza, the last surviving of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; and gain private access to Cairo’s Abdeen Presidential Palace. This mesmerizing destination has entranced archaeologists and historians for generations and inspired its own field of study—Egyptology. Now it’s time for you to be entranced. We look forward to sharing Egypt with you. -

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy

January 2019 Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects Supported by the Legacy Amendment’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund Letter from MNHS CEO and Director In July 2018, I was thrilled to take on the role of the Minnesota Historical Society’s executive director and CEO. As a newcomer to the state, over the last six months, I’ve quickly noticed how strongly Minnesotans value their communities and how proud they are to be from Minnesota. The passage of the Clean Water, Land, and Legacy Amendment in 2008 clearly demonstrates this. I’m inspired by the fact that 10 years ago, Minnesotans voted to commit tax dollars to bettering their state for the future, including preserving our historical and cultural heritage. I’m proud that over 10 years, MNHS has been able to oversee a surge of communities engaging with their local history in new ways, thanks to the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF). As of December 2018, Minnesotans have invested $51 million in history through nearly 2,500 historical and cultural heritage grants in all 87 counties. These grants allow organizations to preserve and share stories about what makes their communities so unique through projects like oral histories, digitization, and new research. Without this funding, this important history can quickly be lost to time. A great example is the Hotel Sacred Heart—explored in our featured stories section —a 1914 hotel on the National Register of Historic Places that’s sat unused since the 1990s. -

The Seated Cleopatra in Nineteenth Century American Sculpture

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1997 The Seated Cleopatra in Nineteenth Century American Sculpture Kelly J. Gotschalk Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4350 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPROVAL CERTIFICATE The Seated Cleopatra in Nineteenth Century AmericanSculpture by Kelly J. Gotschalk Director of Graduate Studies � Dean, School of the Arts Dean, School of Graduate Studies �////PP? Date THE SEATED CLEOPATRA INNINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN SCULPTURE by Kelly J. Gotschalk B.F.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 1990 Submitted to the Faculty of the School of the Arts of Virginia Commonwealth University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements forthe Degree Master of Arts Richmond, Virginia November, 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Fredrika Jacobs and Dr. Charles Brownell fortheir invaluable guidance andendless encouragement in the preparation of this thesis. I would also like to thank my husband, Tom Richards, and my family for their constant support and understanding. In addition, my sincere thanks to my co-workers, Amanda Wilson, Christin Jones and Laurel Hayward fortheir friendship, proofreadingand accommodating a few spur-of-the-moment research trips. ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.. .. .. .. .. .. .. 11 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. iv ABSTRACT ......................................... V JNTRODUCTION. -

United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8s46xqw No online items Inventory of the United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Liz Phillips University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections 2017 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA 95616-5292 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/archives-and-special-collections/ Inventory of the United States O-016 1 Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections Title: United States Theatre Programs Collection Creator: University of California, Davis. Library Identifier/Call Number: O-016 Physical Description: 38.6 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1870-2019 Abstract: Mostly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Researchers should contact Archives and Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Scope and Contents Collection is mainly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Access Collection is open for research. Processing Information Liz Phillips converted this collection list to EAD. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], United States Theatre Programs Collection, O-016, Archives and Special Collections, UC Davis Library, University of California, Davis. Publication Rights All applicable copyrights for the collection are protected under chapter 17 of the U.S. Copyright Code. Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Regents of the University of California as the owner of the physical items. -

Appendix: Famous Actors/ Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom's Cabin

A p p e n d i x : F a m o u s A c t o r s / Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin Uncle Tom Ophelia Otis Skinner Mrs. John Gilbert John Glibert Mrs. Charles Walcot Charles Walcott Louisa Eldridge Wilton Lackaye Annie Yeamans David Belasco Charles R. Thorne Sr.Cassy Louis James Lawrence Barrett Emily Rigl Frank Mayo Jennie Carroll John McCullough Howard Kyle Denman Thompson J. H. Stoddard DeWolf Hopper Gumption Cute George Harris Joseph Jefferson William Harcourt John T. Raymond Marks St. Clare John Sleeper Clarke W. J. Ferguson L. R. Stockwell Felix Morris Eva Topsy Mary McVicker Lotta Crabtree Minnie Maddern Fiske Jennie Yeamans Maude Adams Maude Raymond Mary Pickford Fred Stone Effie Shannon 1 Mrs. Charles R. Thorne Sr. Bijou Heron Annie Pixley Continued 230 Appendix Appendix Continued Effie Ellsler Mrs. John Wood Annie Russell Laurette Taylor May West Fay Bainter Eva Topsy Madge Kendall Molly Picon Billie Burke Fanny Herring Deacon Perry Marie St. Clare W. J. LeMoyne Mrs. Thomas Jefferson Little Harry George Shelby Fanny Herring F. F. Mackay Frank Drew Charles R. Thorne Jr. Rachel Booth C. Leslie Allen Simon Legree Phineas Fletcher Barton Hill William Davidge Edwin Adams Charles Wheatleigh Lewis Morrison Frank Mordaunt Frank Losee Odell Williams John L. Sullivan William A. Mestayer Eliza Chloe Agnes Booth Ida Vernon Henrietta Crosman Lucille La Verne Mrs. Frank Chanfrau Nellie Holbrook N o t e s P R E F A C E 1 . George Howard, Eva to Her Papa , Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture . http://utc.iath.virginia.edu {*}. -

World History

LB 1629 .18 STATE OF lOWA .W67 1930 1930 Courses of Study for High Schools WORLD HISTORY Issued by the Department of Public Instruction AGNES SAMUELSON, Superintendent This book is the property of the district Published by THE STATE OF IOWA Des Moines STATE OF IOWA 1930 Courses· of Study for I High Schools WORLD HISTORY Issued by the Department of P ublic Instruction AGNES SAMUELSON, Superintendent TillS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF THE DISTRICT Published by THE STATE OF IOWA Des Moines CONTENTS Page Foreword 5 Acknowledgments 7 General Introduction 9 Course of Study for World History Introduction 11 I The Dawn of Civilization 14 II Greco-Roman Civilization 18 III Th:e Civilization of the Middle Ages 24 COPYRIGHT 1930 IV 'fhe Transition to Modern Times 30 By the m'ATE OF IOWA V Absolutism and the Struggle for World Power 36 VI An Era of Revolution 42 VII Nationalism and Imperial Expansion 48 VIII The World War and World Reconstruction 54 FORE'WORD This course of study is one of a series of cmriculum publications to be pre sented the high schools of the state from time to time by the Department of Public Instruction. It has been prepared by a subject committee of the Iowa High School Course of Study Commission working under the immediate direction of an Executive Committee. If it is of concrete guidance to the teachers of the state in improving the outcomes of instruction, the major objective of all who have contributed to its construction will have been realized. From the start the need of preparing working materials based upon cardinal objectives and adaptable to classroom situations was emphasized.