How John Delorean Took Us Back to the Future — Introduction —

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boca Raton, Florida 1 Boca Raton, Florida

Boca Raton, Florida 1 Boca Raton, Florida City of Boca Raton — City — Downtown Boca Raton skyline, seen northwest from the observation tower of the Gumbo Limbo Environmental Complex Seal Nickname(s): A City for All Seasons Location in Palm Beach County, Florida Coordinates: 26°22′7″N 80°6′0″W Country United States State Florida County Palm Beach Settled 1895 Boca Raton, Florida 2 Incorporated (town) May, 1925 Government - Type Commission-manager - Mayor Susan Whelchel (N) Area - Total 29.1 sq mi (75.4 km2) - Land 27.2 sq mi (70.4 km2) - Water 29.1 sq mi (5.0 km2) Elevation 13 ft (4 m) Population - Total 86396 ('06 estimate) - Density 2682.8/sq mi (1061.7/km2) Time zone EST (UTC-5) - Summer (DST) EDT (UTC-4) ZIP code(s) Area code(s) 561 [1] FIPS code 12-07300 [2] GNIS feature ID 0279123 [3] Website www.ci.boca-raton.fl.us Boca Raton (pronounced /ˈboʊkə rəˈtoʊn/) is a city in Palm Beach County, Florida, USA, incorporated in May 1925. In the 2000 census, the city had a total population of 74,764; the 2006 population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau was 86,396.[4] However, the majority of the people under the postal address of Boca Raton, about 200,000[5] in total, are not actually within the City of Boca Raton's municipal boundaries. It is estimated that on any given day, there are roughly 350,000 people in the city itself.[6] In terms of both population and land area, Boca Raton is the largest city between West Palm Beach and Pompano Beach, Broward County. -

Academy Award® Winner the Adventures of Robin Hood

ACADEMY AWARD® WINNER THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD (1938) SCREENING SPOTLIGHTS THE PRODUCTION DESIGNS OF CARL JULES WEYL PRESENTED BY THE ART DIRECTORS GUILD FILM SOCIETY AND AMERICAN CINEMATHEQUE Sunday, June 28 at 5:30 PM at the Aero Theatre in Hollywood LOS ANGELES, June 17, 2015 - The Art Directors Guild (ADG) Film Society and American Cinematheque will present a screening of Errol Flynn’s swashbuckling adventure fantasy THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD (1938) spotlighting the production design by Academy Award®- winning designer Carl Jules Weyl, as part of the 2015 ADG Film Series on Sunday, June 28, at 5:30 P.M. at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica. The ADG “Confessions of a Production Designer” Film Series is sponsored by The Hollywood Reporter. “Welcome to Sherwood, my lady!” Legendary, beloved, much imitated but never surpassed, The Adventures of Robin Hood is pure escapism epitomizing the very best in classical Hollywood matinee adventure storytelling. Rich in its visual imagination, it remains a case study in film design excellence. Inspired by the romantic illustrations of famed illustrator and artist N.C. Wyeth, Carl Jules Weyl’s masterful designs served well this Warner Bros.’ first venture into three-strip Technicolor productions. “The Adventures of Robin Hood remains a fitting tribute to the achievements and talent of this exceptional designer, as well as being a reminder of the many less celebrated but equally gifted masters of design who have left us with a visually-inspired legacy,” said Production Designer Thomas A. Walsh, -

The Audiences and Fan Memories of I Love Lucy, the Dick Van Dyke Show, and All in the Family

Viewers Like You: The Audiences and Fan Memories of I Love Lucy, The Dick Van Dyke Show, and All in the Family Mollie Galchus Department of History, Barnard College April 22, 2015 Professor Thai Jones Senior Thesis Seminar 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: I Love Lucy: Widespread Hysteria and the Uniform Audience...................................20 Chapter 2: The Dick Van Dyke Show: Intelligent Comedy for the Sophisticated Audience.........45 Chapter 3: All in the Family: The Season of Relevance and Targeted Audiences........................68 Conclusion: Fan Memories of the Sitcoms Since Their Original Runs.........................................85 Bibliography................................................................................................................................109 2 Acknowledgments First, I’d like to thank my thesis advisor, Thai Jones, for guiding me through the process of writing this thesis, starting with his list of suggestions, back in September, of the first few secondary sources I ended up reading for this project, and for suggesting the angle of the relationship between the audience and the sitcoms. I’d also like to thank my fellow classmates in the senior thesis seminar for their input throughout the year. Thanks also -

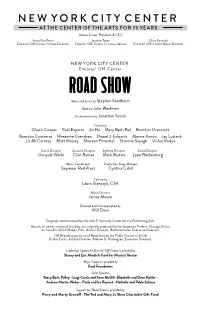

Read the Road Show Program

NEW YORK CITY CENTER AT THE CENTER OF THE ARTS FOR 75 YEARS Arlene Shuler, President & CEO Anne Kauffman Jeanine Tesori Chris Fenwick Encores! Off-Center Artistic Director Encores! Off-Center Creative Advisor Encores! Off-Center Music Director NEW YORK CITY CENTER Encores! Off-Center Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Featuring Chuck Cooper Raúl Esparza Jin Ha Mary Beth Peil Brandon Uranowitz Brandon Contreras Rheaume Crenshaw Daniel J. Edwards Marina Kondo Jay Lusteck Liz McCartney Matt Moisey Shereen Pimentel Sharone Sayegh Vishal Vaidya Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Donyale Werle Clint Ramos Mark Barton Leon Rothenberg Music Coordinator Production Stage Manager Seymour Red Press Cynthia Cahill Casting by Laura Stanczyk, CSA Music Director James Moore Directed and Choreographed by Will Davis Originally commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Bounce, an earlier version of this play, was originally produced by the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois on June 30, 2003 (Robert Falls, Artistic Director; Roche Schulfer, Executive Director). Off-Broadway premiere of Road Show by the Public Theater in 2008 (Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director; Andrew D. Hamingson, Executive Director). Leadership Support for Encores! Off-Center is provided by Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater Major Support is provided by Ford Foundation Series Sponsors Stacy Bash-Polley • Luigi Caiola and Sean McGill • Elizabeth and Dean Kehler • -

"Women and the Silent Screen" In: Wiley-Blackwell History of American

WOMEN AND THE 7 SILENT SCREEN Shelley Stamp Women were more engaged in movie culture at the height of the silent era than they have been at any other time since. Female filmgoers dominated at the box office; the most powerful stars were women, and fan culture catered almost exclusively to female fans; writers shaping film culture through the growing art of movie reviewing, celebrity profiles, and gossip items were likely to be women; and women’s clubs and organizations, along with mass-circulation magazines, played a signature role in efforts to reform the movies at the height of their early success. In Hollywood women were active at all levels of the industry: The top screenwriters were women; the highest-paid director at one point was a woman; and women held key leadership roles in the studios as executives and heads of departments like photography, editing, and screenwriting. Outside Hollywood women ran movie theaters, screened films in libraries and classrooms, and helped to establish venues for nonfiction filmmaking. Looking at the extraordinary scope of women’s participation in early movie culture – indeed, the way women built that movie culture – helps us rethink conventional ideas about authorship and the archive, drawing in a broader range of players and sources. As Antonia Lant reminds us, the binary notion of women working on “both sides of the camera” needs to be significantly complicated and expanded in order to accommodate all of the ways in which women engaged with and produced early film culture (2006, 548–549). The Wiley-Blackwell History of American Film, First Edition. -

ROAD SHOW January 2

LAWRENCE HELMAN PUBLIC RELATIONS – E MAIL - [email protected] nd 1643 32 Ave. SF, CA 94122 - Tel. 415 /661- 1260 / Cell. 415/ 336- 8220 (DO NOT PUBLISH THIS #) FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Nov. 25, 2013.- For press materials and hi-res color press photos, visit: http://www.therhino.org/press.htm Theatre Rhinoceros presents… The Bay Area Premiere of the Stephen Sondheim Musical ROAD SHOW Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Starring Bill Fahrner * and Rudy Guerrero* Musical Direction by Dave Dobrusky Directed by John Fisher Bay Area Premiere - Limited Engagement - 15 Performances Only! January 2 – 19, 2014 - MUST CLOSE JANUARY 19 Wed. - Sat. - 8:00 pm / Sun. - 3:00 pm Previews Jan. 2 & 3 (Thurs. & Fri.) – Opens Sat. Jan. 4 - 8:00 pm Eureka Theatre in SF www.TheRhino.org *Member Actor’s Equity Association Trailer: http://tinyurl.com/kweqjmf “Addison and Wilson Mizner were born within a year and a half of each other in the early 1870s in Benicia, CA. During the course of their long, colorful and often chaotic lives, they criss-crossed the country – sometimes separately, sometimes together – trying their hands at a dizzying array of different enterprises and pursuits from prospecting for gold in the Yukon to promoting a utopian real-estate venture during the Florida land boom. Addison died in Palm Beach in 1933, leaving behind a handful of uniquely designed Mizner houses. Wilson died within weeks of him, in Hollywood. ROAD SHOW is the story of their lives – or at any rate our version of it.” - Stephen Sondheim & John Weidman Theatre Rhino does Sondheim. -

That's Television Entertainment: the History, Development, and Impact

That’s Television Entertainment: The History, Development, and Impact of the First Five Seasons of “Entertainment Tonight,” 1981-86 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Sara C. Magee August 2008 © 2008 Sara C. Magee All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation titled That’s Television Entertainment: The History, Development, and Impact of the First Five Seasons of “Entertainment Tonight,” 1981-86 by SARA C. MAGEE has been approved for the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism and the Scripps College of Communication by Patrick S. Washburn Professor of Journalism Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication iii Abstract MAGEE, SARA C., Ph.D., August 2008, Mass Communication That’s Television Entertainment: The History, Development, and Impact of the First Five Seasons of “Entertainment Tonight,” 1981-86 (306 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Patrick S. Washburn The line between news and entertainment on television grows more blurry every day. Heated debates over what is news and what is entertainment pepper local, national, and cable newsrooms. Cable channels devoted entirely to entertainment and a plethora of syndicated, half-hour entertainment news magazines air nightly. It was not always so. When “Entertainment Tonight” premiered in 1981, the first daily half-hour syndicated news program, no one thought it would survive. No one believed there was enough celebrity and Hollywood news to fill a daily half-hour, much less interest an audience. Still, “ET” set out to become the glitzy, glamorous newscast of record for the entertainment industry and twenty-seven years later is still going strong. -

Jolly Fellows Stott, Richard

Jolly Fellows Stott, Richard Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Stott, Richard. Jolly Fellows: Male Milieus in Nineteenth-Century America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3440. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3440 [ Access provided at 28 Sep 2021 22:09 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Jolly Fellows gender relations in the american experience Joan E. Cashin and Ronald G. Walters, Series Editors Jolly Fellows Male Milieus in Nineteenth-Century America D richard stott The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2009 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 246897531 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stott, Richard Briggs. Jolly fellows : male milieus in nineteenth-century America / Richard Stott. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-8018-9137-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-8018-9137-x (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Men—United States—History—19th century. 2. Men—Psychology— History—19th century. 3. Masculinity—United States—History—19th century. 4. Violence in men—United States. I. Title. hq1090.3.s76 2009 305.38'96920907309034—dc22 2008044003 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or [email protected]. -

Thousand Oaks Library American Radio Archives

Thousand Oaks Library American Radio Archives Howard Hoffman Collection Howard Hoffman (1954- ) is a voice actor and broadcast branding producer in Washington State and operates the internet radio station Great Big Radio. He was the host of Top 40 radio shows on the east as well as the west coast. From 1994 to 2011 Howard was the creative/production director at KABC Radio and unofficial historian of the station. His collection includes: Blue Network scripts (incl. news) correspondence and memos from the 1940s and '50s schedules of war messages news, correspondence and memos from the 1940s and '50s KABC PR material and photos - 1990s Scripts 18th Annual Academy Award 03-07-1946 Abbott & Costello 10-22-1947 004 11-05-1947 006 12-31-1947 014 03-24-1948 026 ABC Radio Workshop, The 09-06-1950 A Case of Nerves 10-24-1950 Taps for Jeffrey 11-14-1950 My Sister Eileen 03/1951 The Life of Florence Nightingale 04/1951 A Shipment of Mute Fate 01/1952 002 The Word ABC Round Table 06-06-1942 Adventure Playhouse 01-02-1948 Ginger (audition) Adventures of Bill Lance, The 12-28-1947 The Case of the Final Page 01-04-1948 The Case of the Man Who Murdered Himself Adventures of Ellery Queen, The 12-25-1947 333 (ABC #5) Ellery Queen - Santa Claus 01-01-1948 334 (ABC #6) The Silly Case 01-08-1948 335 (ABC #7) The Head Hunter 03-25-1948 346 (ABC #18) The Farmer's Daughter 05-06-1948 352 (ABC #24) One Diamond 05-13-1948 353 (ABC #25) Nikki Porter, Starlet 05-20-1948 354 (ABC #26) Misery Mike Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet 01-20-1950 015 The Explorers 01-27-1950 016 The Riviera Ballet 03-17-1950 023 The Blarney Stone 09-29-1950 004 The Necktie 10-06-1950 005 New Chairs 10-20-1950 007 Physical Fitness 10-19-1951 008 The Clean-up Caper 11-09-1951 007 Aptitudes: Male vs. -

The Curdling of American History

TThhee CCuurrddlliinngg ooff AAmmeerriiccaann HHiissttoorryy ‘‘MM’’ A Recap of the Exodus that transformed Hollywood from Starlit Mecca to Celebrity Babylon by Nick Zegarac “Hollywood is a place where they place you under contract instead of under observation.” – Walter Winchell The history of Hollywood is only one third fairytale. No, that’s not entirely true or open-minded to the reputation of the fairytale – except if one regards those watered down predigested versions made for the kiddies by Disney. No, Hollywood is all fairytale, as in the Brothers Grimm; both the light and the fantastic, and, the disturbing and the frightfully dismal - effortlessly blended in one tight-knit community. Hollywood’s earliest moments are a history of trial and error; a tale about making great strides through blind ambition despite steadfast adversities. It is a history of the 20th century’s most resilient art form, even though eighty percent of that art has been lost for all time through recent shortsightedness and a very public neglect that almost universally failed to preserve or even classify motion pictures as anything beyond cheap thrills entertainment. (at right: Natalie and Herbert Kalmus: he the great inventor and pioneer of the 3-strip Technicolor process, she the woman behind the man who would forever be associated with the company and its output than he. A bitter separation and divorce left Mrs. Kalmus with the right to insist her name be accredited to every Technicolor film made between 1929 and 1953, a right that made her a very rich divorcee indeed.) (Left: The man who might have been king – at least of comedy: Roscoe Fatty Arbuckle. -

An American Tour: 73

An American Tour: 73 Los Angeles’s Brown Derby The Brown Derby was the name of a chain of restaurants in Los Angeles, California. The first and most famous of these was shaped like a man's derby hat, an iconic image that became synonymous with the Golden Age of Hollywood. A chain of Brown Derby restaurants in Ohio are still in business today. The chain was started by Robert H. Cobb and Herbert Somborn (a former husband of Gloria Swanson). It is often incorrectly thought that the Brown Derby was a single restaurant, and the Wilshire Boulevard and Hollywood branches are frequently confused. Gus Girves started the Brown Derby chain in Ohio in 1941. Opened in 1926, the original restaurant at 3427 Wilshire Boulevard remains the most famous due to its distinctive shape. Whimsical architecture was popular at the time, and the restaurant was designed to catch the eye of passing motorists. It is said that the shape of the hat worn by New York governor and 1928 Democratic Party presidential candidate Al Smith, a personal friend of Somborn's, was an inspiration. Another theory claims that Somborn was told a good restaurateur could serve food out of a hat and still make a success of it. The small cafe, close to popular Hollywood hot spots such as Cocoanut Grove at the Ambassador Hotel, became successful enough to warrant building a second branch. The original, derby-shaped building was moved in 1937 to 3377 Wilshire Boulevard at the northeast corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Alexandria Avenue, about a block from its previous location (just north of the Ambassador Hotel). -

Ebook ^ Stephen Sondheim: Road Show > Download

Stephen Sondheim: Road Show < Book // 2OI8AYEA5C Steph en Sondh eim: Road Sh ow By - Hal Leonard Corporation. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Stephen Sondheim: Road Show, "Addison Mizner and Wilson Mizner were brothers who, although they played only a minor role in the cultural history of this country, might well be seen to represent two divergent aspects of American energy: the builder and the squanderer."--Stephen Sondheim "The score is full of delights, intelligence and tension . with a tight, funny book."--New York Daily News Road Show, Stephen Sondheim's first musical since his 1994 Tony Award-winner Passion, is making its highly anticipated New York premiere this season at the Public Theater. The show--with the book by John Weidman, Sondheim's collaborator from Pacific Overtures and Assassins--has been in development for several years with productions in Chicago and Washington, DC, and grew from an idea that germinated in Sondheim's mind some fifty years ago. The show dramatizes the real-life Mizner brothers, following their fortunes from the 1890s Alaskan gold rush to the 1920s Florida land boom: Addison as an architect and Wilson as a con man, each brother seeking his own American dream. Stephen Sondheim's career spans from his work as lyricist for West Side Story and Gypsy, to composer/lyricist on such masterpieces as... READ ONLINE [ 3.97 MB ] Reviews It is not diicult in go through easier to understand. It normally fails to price too much. I am very happy to inform you that this is actually the greatest ebook i actually have read through within my personal lifestyle and can be he best publication for ever.