Bernard Leach – (1887 – 1979)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamada Shōji (1894-1978)

HAMADA SHŌJI (1894-1978) Hamada Shōji attained unsurpassed recognition at home and abroad for his folk art style ceramics. Inspired by Okinawan and Korean ceramics in particular, Hamada became an important figure in the Japanese folk arts movement in the 1960s. He was a founding member of the Japan Folk Art Association with Bernard Leach, Kawai Kanjirō, and Yanagi Soetsu. After 1923, he moved to Mashiko where he rebuilt farmhouses and established his large workshop. Throughout his life, Hamada demonstrated an excellent glazing technique, using such trademark glazes as temmoku iron glaze, nuka rice-husk ash glaze, and kaki persimmon glaze. Through his frequent visits and demonstrations abroad, Hamada influenced many European and American potters in later generations as well as those of his own. 1894 Born in Tokyo 1912 Saw etchings and pottery by Bernard Leach in Ginza, Tokyo 1913 Studied at the Tokyo Technical College with Itaya Hazan (1872-1963) Became friends with Kawai Kanjiro (1890-1966) and visits in Kyoto (1915) 1914 Became interested in Mashiko pottery after seeing a teapot at Hazan's home 1916 Graduated from Tokyo Technical College and enrolled at Kyoto Ceramics Laboratory, visits with Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886-1963) Began 10,000 glaze experiments with Kawai 1917 Visited Okinawa to study kiln construction 1919 Met Bernard Leach (1887-1979) at his Tokyo exhibition, invited to him his studio in Abiko where meets Yanagi Sōetsu (1889-1961) Traveled to Korea and Manchuria, China with Kawai 1920 Visited Mashiko for the first time Traveled to England with Leach, built a climbing kiln at St. Ives 1923 Traveled to France, Italy, Crete, and Egypt after his solo exhibition in London 1924 Moved to Mashiko. -

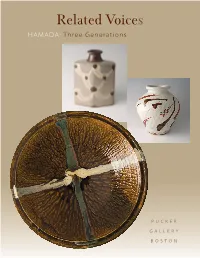

Related Voices Hamada: Three Generations

Related Voices HAMADA: Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY BOSTON Tomoo Hamada Shoji Hamada Bottle Obachi (Large Bowl), 1960-69 Black and kaki glaze with akae decoration Ame glaze with poured decoration 12 x 8 ¼ x 5” 4 ½ x 20 x 20” HT132 H38** Shinsaku Hamada Vase Ji glaze with tetsue and akae decoration Shoji Hamada 9 ¾ x 5 ¼ x 5 ¼” Obachi (Large Bowl), ca. 1950s HS36 Black glaze with trailing decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40** *Box signed by Shoji Hamada **Box signed by Shinsaku Hamada All works are stoneware. Three Voices “To work with clay is to be in touch with the taproot of life.’’ —Shoji Hamada hen one considers ceramic history in its broadest sense a three-generation family of potters isn’t particularly remarkable. Throughout the world potters have traditionally handed down their skills and knowledge to their offspring thus Wmaintaining a living history that not only provided a family’s continuity and income but also kept the traditions of vernacular pottery-making alive. The long traditions of the peasant or artisan potter are well documented and can be found in almost all civilizations where the generations are to be numbered in the tens or twenties or even higher. In Africa, South America and in Asia, styles and techniques remained almost unaltered for many centuries. In Europe, for example, the earthenware tradition existed from the early Middle Ages to the very beginning of the 20th century. Often carried on by families primarily involved in farming, it blossomed into what we would now call the ‘slipware’ tradition. The Toft family was probably the best known makers of slipware in Staffordshire. -

The Leach Pottery: 100 Years on from St Ives

The Leach Pottery: 100 years on from St Ives Exhibition handlist Above: Bernard Leach, pilgrim bottle, stoneware, 1950–60s Crafts Study Centre, 2004.77, gift of Stella and Nick Redgrave Introduction The Leach Pottery was established in St Ives, Cornwall in the year 1920. Its founders were Bernard Leach and his fellow potter Shoji Hamada. They had travelled together from Japan (where Leach had been living and working with his wife Muriel and their young family). Leach was sponsored by Frances Horne who had set up the St Ives Handicraft Guild, and she loaned Leach £2,500 as capital to buy land and build a small pottery, as well as a sum of £250 for three years to help with running costs. Leach identified a small strip of land (a cow pasture) at the edge of St Ives by the side of the Stennack stream, and the pottery was constructed using local granite. A tiny room was reserved for Hamada to sleep in, and Hamada himself built a climbing kiln in the oriental style (the first in the west, it was claimed). It was a humble start to one of the great sites of studio pottery. The Leach Pottery celebrates its centenary year in 2020, although the extensive programme of events and exhibitions planned in Britain and Japan has been curtailed by the impact of Covid-19. This exhibition is the tribute of the Crafts Study Centre to the history, legacy and continuing significance of The Leach Pottery, based on the outstanding collections and archives relating firstly to Bernard Leach. -

Bernard Leach and His Circle

Bernard Leach and his Circle Spring 2008 26 January – 11 May 2008 Notes for Teachers Information and practical ideas for groups Written by Angie MacDonald Ceramics by Bernard Leach and key studio potters who worked alongside him can be seen in the Showcase (Upper Gallery 2). These works form part of the Wingfield-Digby Collection, recently gifted to Tate St Ives. For discussion • There has been much discussion in recent years as to whether ceramics is an art or a craft. Leach insisted that he was an ‘artist-potter’ and he always regarded his individual pots as objects of art rather than craft. • Why do you think he considered these pots more important than the standard ware (tableware)? • What do you think the display at Tate St Ives says about the status of these objects? Are they sculptures or domestic objects? • The Japanese critic Soetsu Yanagi complimented Leach by describing his earthenware as ‘born not made’. What do you think he meant by this? • Leach said he wanted his pots to have ‘vitality’ – to capture a sense of energy and life. Can you find examples that you feel have this quality? • The simplified motif of a bird was a favourite for Leach. He considered it a symbol of freedom and peace. Can you find other motifs in his work and what do you think they symbolise? Things to think about This stoneware tile has the design of a bird feeding its young, painted in iron. It has sgraffito detailing where Leach scratched through the wet clay slip before firing. It is an excellent example of Leach’s commitment to quiet, contemplative forms with soft, muted colours derived from the earth. -

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition in Modern Japanese Ceramics of the Postwar Period Comparison of a Vase by Hamada Shōji and a Jar by Kitaōji Rosanjin Grant Akiyama Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory, School of Art and Design Division of Art History New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University Alfred, New York 2017 Grant Akiyama, BS Dr. Hope Marie Childers, Thesis Advisor Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the patience and wisdom of my advisor, Dr. Hope Marie Childers. I thank Dr. Meghen Jones for her insights and expertise; her class on East Asian crafts rekindled my interest in studying Japanese ceramics. Additionally, I am grateful to the entire Division of Art History. I thank Dr. Mary McInnes for the rigorous and unique classroom experience. I thank Dr. Kate Dimitrova for her precision and introduction to art historical methods and theories. I thank Dr. Gerar Edizel for our thought-provoking conversations. I extend gratitude to the libraries at Alfred University and the collections at the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum. They were invaluable resources in this research. I thank the Curator of Collections and Director of Research, Susan Kowalczyk, for access to the museum’s collections and records. I thank family and friends for the support and encouragement they provided these past five years at Alfred University. I could not have made it without them. Following the 1950s, Hamada and Rosanjin were pivotal figures in the discourse of American and Japanese ceramics. -

Bernard Leach and British Columbian Pottery: an Historical Ethnography of a Taste Culture

BERNARD LEACH AND BRITISH COLUMBIAN POTTERY: AN HISTORICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A TASTE CULTURE by Nora E. Vaillant B. A. Swarthmore College, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Department of Anthropology and Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia October 2002 © Nora E. Vaillant, 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of J^j'thiA^^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This thesis presents an historical ethnography of the art world and the taste culture that collected the west coast or Leach influenced style of pottery in British Columbia. This handmade functional style of pottery traces its beginnings to Vancouver in the 1950s and 1960s, and its emergence is embedded in the cultural history of the city during that era. The development of this pottery style is examined in relation to the social network of its founding artisans and its major collectors. The Vancouver potters Glenn Lewis, Mick Henry and John Reeve apprenticed with master potter Bernard Leach in England during the late fifties and early sixties. -

Of Gallery Marianne Heller

GALLERY 1978 – 2013 35th ANNIVERSARY OF GALLERY MARIANNE HELLER t is always enthusiastic individuals who make a difference. Walter H. Lokau Marianne Heller is just such an enthusiastic individual who Isets things in motion. As a gallery owner, she has dedicated herself to publicising contemporary international ceramics, and she The tale of someone who has been doing this for 35 years. One thing has remained in all this time: her untiring enthusiasm for contemporary ceramics and her set out to bring the world uncompromising desire to make quality ceramics accessible to the public that are otherwise rare in this part of the world. That is what of ceramics to Germany … has remained, but quite a lot of other things have changed in three and a half decades… chael Casson, David Frith, John Maltby, Svend Bayer and oth- The 1970s – the time of self-fulfilment. A passion for peasant ers debuted here with their pots – the whole business grew in pottery had taken hold of Marianne Heller. Were there no contem- no time. Once a year from 1982, the Festhalle in Sandhausen porary ceramics? She looked around. Inevitably a pottery course became the venue for the English Potters' Seminar: a public followed. But she soon left making ceramics herself well alone. By workshop after the English model, and previously unknown in chance, she got her hands on Bernard Leach's A Potter's Book. It was this kind in Germany, intending to teach techniques and at the a revelation! Leach's doctrine of the wheel-thrown vessel, which was same time to develop taste and judgement. -

The Ceramics of KK Broni, a Ghanaian Protégé of Michael

Review of Arts and Humanities June 2020, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 13-24 ISSN: 2334-2927 (Print), 2334-2935 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/rah.v9n1a3 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/rah.v9n1a3 Bridging Worlds in Clay: The Ceramics of K. K. Broni, A Ghanaian protégé of Michael Cardew And Peter Voulkos Kofi Adjei1 Keaton Wynn2 kąrî'kạchä seid’ou1 Abstract Kingsley Kofi Broni was a renowned ceramist with extensive exposure and experience in studio art practice. He was one of the most experienced and influential figures in ceramic studio art in Africa. Broni was trained by the famous Michael Cardew at Abuja, Nigeria, Peter Voulkos in the United States, and David Leach, the son of Bernard Leach, in England. Broni had the experience of meeting Bernard Leach while in England and attended exhibitions of Modern ceramists such as Hans Coper. His extensive education, talent, and hard work, coupled with his diverse cultural exposure, make him one of Africa‘s most accomplished ceramists of the postcolonial era. He is credited with numerous national and international awards. He taught for 28 years in the premiere College of Art in Ghana, at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi. Broni has had an extensive exhibition record and has a large body of work in his private collection. This study seeks to unearth and document the contribution of the artist Kingsley Kofi Broni and position him within the broader development of ceramic studio art in Ghana, revealing the significance of his work within the history of Modern ceramics internationally. -

Leach Pottery Announce Collaborative Project to Restore Documentary Film Compendium on Bernard Leach and the Mingei Movement

Leach Pottery Announce Collaborative Project to Restore Documentary Film Compendium on Bernard Leach and the Mingei Movement The Leach Pottery and Marty Gross Film Productions, Canada, announce their collaboration in the restoration and re-release of historically important films from the 1930’s to the 1970’s which profile key figures in the history of The Leach Pottery and the Japanese Mingei Movement. The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation have provided a generous £5000 donation in support of this unique project, and following this initial funding further funding has been pledged or received from The Museum of Ceramic Art New York, Ceramica Stiftung Basel, Warren and Nancy MacKenzie, scholar Dr. Paul Griffith and art collector Dr. John Driscoll. Film subjects include Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, Soetsu Yanagi, Janet Leach, William Marshall and others. Bernard Leach, founder of The Leach Pottery, was an important figure in the history of contemporary ceramics and a key member of the group that founded the Mingei Movement. His writings on Japan and its ceramic traditions are central documents in the history of the Modern craft movement. Over the neXt three years, the project will restore and digitize important and never before seen footage which documents the studies of Bernard Leach and his colleagues in Japan as they developed ideas that became central to the Mingei movement. The resulting compendium will consist of DVDs and a booklet containing the following films and new documentation: ▪ Trip to Japan, filmed by Bernard Leach, 1934-35 ▪ Mashiko Village Pottery, Japan 1937 ▪ Bernard Leach visit to San Francisco, 1950 ▪ The Art of the Potter (1971), by David Outerbridge and Sidney Reichman ▪ Excerpts from 10 hours of unseen film footage from The Art of the Potter ▪ An exclusive Video Interview by Marty Gross with Mihoko Okamura, D.T. -

A Potters Book Free Ebook

FREEA POTTERS BOOK EBOOK Bernard Leach | 372 pages | 23 Feb 2012 | FABER & FABER | 9780571283675 | English | London, United Kingdom A Potter's Book Harry Potter is a series of seven fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the lives of a young wizard, Harry Potter, and his friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, all of whom are students at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. A Potter's Book by Bernard Leach with introductions by Soyetsu Yanagi and Michael Cardew. This is the first treatise by a potter on the workshop traditions which have been handed down by Koreans and Japanese from the greatest period of Chinese ceramics in the Sung dynasty. This now famous book was the first treatise to be written by a potter on the workshop traditions handed down by Koreans and Japanese from the greatest period of Chinese ceramics in the Sung dynasty. It deals with four types of pottery: Japanese raku, English slipware, stoneware and oriental porcelain. Potters Book by Leach Bernard A Potter Book by Bernard Leach. Topics IIIT Collection digitallibraryindia; JaiGyan Language English. Book Source: Digital Library of India Item In A Potter's Workbook, renowned studio potter and teacher Clary Illian presents a textbook for the hand and the mind. Her aim is to provide a way to see, to make, and to think about the forms of wheel-thrown vessels; her information and inspiration explain both the mechanics of throwing and finishing pots made simply on the wheel and the principles of truth and beauty arising from that traditional method. -

2011 Gallery Catalogue

A SELLING EXHIBITION OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY SLIPWARES Long Room Gallery Winchcombe 12th to 26th November 2011 JOHN EDGELER & ROGER LITTLE PRESENT A SELLING EXHIBITION OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY SLIPWARES FROM THE WINCHCOMBE AND ST IVES POTTERIES 12th to 26th November 2011, 9.30am to 5.00pm Monday to Saturday (from midday on first day) Long Room Gallery, Queen Anne House, High Street, Winchcombe, Gloucestershire, GL54 5LJ Telephone: 01242 602319 Website: www.cotswoldsliving.co.uk Show terms and conditions Condition: Due to their low fired nature, slipwares are prone to chipping and flaking, and all the pots for sale were originally wood fired in traditional bottle or round kilns, with all the faults and delightful imperfections entailed. We have endeavoured to be as accurate as possible in our descriptions, and comment is made on condition where this is materially more than the normal wear and tear of 80 to 100 years. For the avoidance of any doubt, purchasers are recommended to inspect pots in person. Payment: Payment must be made in full on purchase, and pots will normally be available for collection at the close of the show, in this case on Saturday 26th November 2010. Settlement may be made in cash or by cheque, lthough a clearance period of five working days is required in the latter case. Overseas buyers are recommended to use PayPal as a medium, for the avoidance of credit card charges. Postal delivery: we are unable to provide insured delivery for overseas purchasers, although there are a number of shipping firms that buyers may choose to commission. -

Yuko Kikuchi Hybridity and the Oriental Orientalism of Mingei Theory Downloaded From

Yuko Kikuchi Hybridity and the Oriental Orientalism of Mingei Theory Downloaded from Orientalism is not a rigid one-way phenomenon projected on to the Orient from the Occident. It is an infectious phenomenon, open to appropriation by 'others', at least in the case of modern Japan. This article presents a case study o/Mingei (folk crafts) theory created by Yanagi Soetsu and evaluated in the Occident as an 'Oriental' theory for what is deemed to be its greatest merit—'traditional authenticity'. The intention of this article is firstly to demystify the essential 'Orientalness' o/Mingei http://jdh.oxfordjournals.org/ theory by showing its 'hybrid' nature and the process of hybridization involved in the course of its formation; and secondly to show the strategic significance of 'hybridity' in the context of Japanese cultural nationalism in the dichotomic framework of Orient and Occident. This article presents a case study of Japanese Japanese art in the nineteenth century, following objects in the modern period as related to on from interest in the art of China, India and the 1 Yanagi Soetsu (1889-1961) [1] and his Mingei Middle East. 'Orientalism' is an integral part of at UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS LONDON on October 6, 2014 (folk crafts) theory, Japan's first modern craft/ the discipline for studying Japanese art, and has design theory created in the 1920s. The main focus been particularly evident in the way the Occident of discussion is on the creation of a Japanese defined Japan as medieval and primitive, and as a national identity, the invention of Japanese 'tradi- country of 'decorative art' without 'fine art'.