Global Relational Models of Source Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executable Code Is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law a Retrospective Criticism of Technical and Legal Naivete in the Apple V

Executable Code is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law A retrospective criticism of technical and legal naivete in the Apple V. Franklin case Matthew M. Swann, Clark S. Turner, Ph.D., Department of Computer Science Cal Poly State University November 18, 2004 Abstract: Copyright was created by government for a purpose. Its purpose was to be an incentive to produce and disseminate new and useful knowledge to society. Source code is written to express its underlying ideas and is clearly included as a copyrightable artifact. However, since Apple v. Franklin, copyright has been extended to protect an opaque software executable that does not express its underlying ideas. Common commercial practice involves keeping the source code secret, hiding any innovative ideas expressed there, while copyrighting the executable, where the underlying ideas are not exposed. By examining copyright’s historical heritage we can determine whether software copyright for an opaque artifact upholds the bargain between authors and society as intended by our Founding Fathers. This paper first describes the origins of copyright, the nature of software, and the unique problems involved. It then determines whether current copyright protection for the opaque executable realizes the economic model underpinning copyright law. Having found the current legal interpretation insufficient to protect software without compromising its principles, we suggest new legislation which would respect the philosophy on which copyright in this nation was founded. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 THE ORIGIN OF COPYRIGHT ........................................................................... 1 The Idea is Born 1 A New Beginning 2 The Social Bargain 3 Copyright and the Constitution 4 THE BASICS OF SOFTWARE .......................................................................... -

Studying the Real World Today's Topics

Studying the real world Today's topics Free and open source software (FOSS) What is it, who uses it, history Making the most of other people's software Learning from, using, and contributing Learning about your own system Using tools to understand software without source Free and open source software Access to source code Free = freedom to use, modify, copy Some potential benefits Can build for different platforms and needs Development driven by community Different perspectives and ideas More people looking at the code for bugs/security issues Structure Volunteers, sponsored by companies Generally anyone can propose ideas and submit code Different structures in charge of what features/code gets in Free and open source software Tons of FOSS out there Nearly everything on myth Desktop applications (Firefox, Chromium, LibreOffice) Programming tools (compilers, libraries, IDEs) Servers (Apache web server, MySQL) Many companies contribute to FOSS Android core Apple Darwin Microsoft .NET A brief history of FOSS 1960s: Software distributed with hardware Source included, users could fix bugs 1970s: Start of software licensing 1974: Software is copyrightable 1975: First license for UNIX sold 1980s: Popularity of closed-source software Software valued independent of hardware Richard Stallman Started the free software movement (1983) The GNU project GNU = GNU's Not Unix An operating system with unix-like interface GNU General Public License Free software: users have access to source, can modify and redistribute Must share modifications under same -

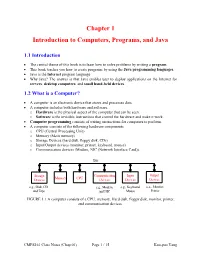

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

Some Preliminary Implications of WTO Source Code Proposala INTRODUCTION

Some preliminary implications of WTO source code proposala INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 HOW THIS IS TRIMS+ ....................................................................................................................................... 3 HOW THIS IS TRIPS+ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE TRANSFER OF SOURCE CODE .................................................................. 4 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ........................................................................................................................................... 4 AS A REMEDY FOR ANTICOMPETITIVE CONDUCT ............................................................................................................. 4 TAX LAW ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 IN GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ................................................................................................................................ 5 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE ACCESS TO SOURCE CODE ...................................................................... 5 COMPETITION LAW ................................................................................................................................................. -

Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK

1 From Start-ups to Scale-ups: Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK Abstract—This paper1 describes some of the challenges and research questions that target the most productive intersection opportunities when deploying static and dynamic analysis at we have yet witnessed: that between exciting, intellectually scale, drawing on the authors’ experience with the Infer and challenging science, and real-world deployment impact. Sapienz Technologies at Facebook, each of which started life as a research-led start-up that was subsequently deployed at scale, Many industrialists have perhaps tended to regard it unlikely impacting billions of people worldwide. that much academic work will prove relevant to their most The paper identifies open problems that have yet to receive pressing industrial concerns. On the other hand, it is not significant attention from the scientific community, yet which uncommon for academic and scientific researchers to believe have potential for profound real world impact, formulating these that most of the problems faced by industrialists are either as research questions that, we believe, are ripe for exploration and that would make excellent topics for research projects. boring, tedious or scientifically uninteresting. This sociological phenomenon has led to a great deal of miscommunication between the academic and industrial sectors. I. INTRODUCTION We hope that we can make a small contribution by focusing on the intersection of challenging and interesting scientific How do we transition research on static and dynamic problems with pressing industrial deployment needs. Our aim analysis techniques from the testing and verification research is to move the debate beyond relatively unhelpful observations communities to industrial practice? Many have asked this we have typically encountered in, for example, conference question, and others related to it. -

Language Translators

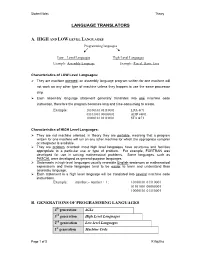

Student Notes Theory LANGUAGE TRANSLATORS A. HIGH AND LOW LEVEL LANGUAGES Programming languages Low – Level Languages High-Level Languages Example: Assembly Language Example: Pascal, Basic, Java Characteristics of LOW Level Languages: They are machine oriented : an assembly language program written for one machine will not work on any other type of machine unless they happen to use the same processor chip. Each assembly language statement generally translates into one machine code instruction, therefore the program becomes long and time-consuming to create. Example: 10100101 01110001 LDA &71 01101001 00000001 ADD #&01 10000101 01110001 STA &71 Characteristics of HIGH Level Languages: They are not machine oriented: in theory they are portable , meaning that a program written for one machine will run on any other machine for which the appropriate compiler or interpreter is available. They are problem oriented: most high level languages have structures and facilities appropriate to a particular use or type of problem. For example, FORTRAN was developed for use in solving mathematical problems. Some languages, such as PASCAL were developed as general-purpose languages. Statements in high-level languages usually resemble English sentences or mathematical expressions and these languages tend to be easier to learn and understand than assembly language. Each statement in a high level language will be translated into several machine code instructions. Example: number:= number + 1; 10100101 01110001 01101001 00000001 10000101 01110001 B. GENERATIONS OF PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES 4th generation 4GLs 3rd generation High Level Languages 2nd generation Low-level Languages 1st generation Machine Code Page 1 of 5 K Aquilina Student Notes Theory 1. MACHINE LANGUAGE – 1ST GENERATION In the early days of computer programming all programs had to be written in machine code. -

INTRODUCTION to .NET FRAMEWORK NET Framework .NET Framework Is a Complete Environment That Allows Developers to Develop, Run, An

INTRODUCTION TO .NET FRAMEWORK NET Framework .NET Framework is a complete environment that allows developers to develop, run, and deploy the following applications: Console applications Windows Forms applications Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) applications Web applications (ASP.NET applications) Web services Windows services Service-oriented applications using Windows Communication Foundation (WCF) Workflow-enabled applications using Windows Workflow Foundation (WF) .NET Framework also enables a developer to create sharable components to be used in distributed computing architecture. NET Framework supports the object-oriented programming model for multiple languages, such as Visual Basic, Visual C#, and Visual C++. NET Framework supports multiple programming languages in a manner that allows language interoperability. This implies that each language can use the code written in some other language. The main components of .NET Framework? The following are the key components of .NET Framework: .NET Framework Class Library Common Language Runtime Dynamic Language Runtimes (DLR) Application Domains Runtime Host Common Type System Metadata and Self-Describing Components Cross-Language Interoperability .NET Framework Security Profiling Side-by-Side Execution Microsoft Intermediate Language (MSIL) The .NET Framework is shipped with compilers of all .NET programming languages to develop programs. Each .NET compiler produces an intermediate code after compiling the source code. 1 The intermediate code is common for all languages and is understandable only to .NET environment. This intermediate code is known as MSIL. IL Intermediate Language is also known as MSIL (Microsoft Intermediate Language) or CIL (Common Intermediate Language). All .NET source code is compiled to IL. IL is then converted to machine code at the point where the software is installed, or at run-time by a Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler. -

18Mca42c .Net Programming (C#)

18MCA42C .NET PROGRAMMING (C#) Introduction to .NET Framework .NET is a software framework which is designed and developed by Microsoft. The first version of .Net framework was 1.0 which came in the year 2002. It is a virtual machine for compiling and executing programs written in different languages like C#, VB.Net etc. It is used to develop Form-based applications, Web-based applications, and Web services. There is a variety of programming languages available on the .Net platform like VB.Net and C# etc.,. It is used to build applications for Windows, phone, web etc. It provides a lot of functionalities and also supports industry standards. .NET Framework supports more than 60 programming languages in which 11 programming languages are designed and developed by Microsoft. 11 Programming Languages which are designed and developed by Microsoft are: C#.NET VB.NET C++.NET J#.NET F#.NET JSCRIPT.NET WINDOWS POWERSHELL IRON RUBY IRON PYTHON C OMEGA ASML(Abstract State Machine Language) Main Components of .NET Framework 1.Common Language Runtime(CLR): CLR is the basic and Virtual Machine component of the .NET Framework. It is the run-time environment in the .NET Framework that runs the codes and helps in making the development process easier by providing the various services such as remoting, thread management, type-safety, memory management, robustness etc.. Basically, it is responsible for managing the execution of .NET programs regardless of any .NET programming language. It also helps in the management of code, as code that targets the runtime is known as the Managed Code and code doesn’t target to runtime is known as Unmanaged code. -

Namespaces, Source Code Analysis, and Byte Code Compilation User! 2004

Namespaces, Source Code Analysis, and Byte Code Compilation UseR! 2004 Introduction Namespaces, Source Code Analysis, • R is a powerful, high level language. and Byte Code Compilation • As R is used for larger programs there is a need for tools to Luke Tierney – help make code more reliable and robust Department of Statistics & Actuarial Science – help improve performance University of Iowa • This talk outlines three approaches: – name space management – code analysis tools – byte code compilation 1 Namespaces, Source Code Analysis, and Byte Code Compilation UseR! 2004 Namespaces, Source Code Analysis, and Byte Code Compilation UseR! 2004 Why Name Spaces Static Binding of Globals Two issues: • R functions usually use other functions and variables: • static binding of globals f <- function(z) 1/sqrt(2 * pi)* exp(- z^2 / 2) • hiding internal functions • Intent: exp, sqrt, pi from base. Common solution: name space management tools. • Dynamic global environment: definitions in base can be masked. 2 3 Namespaces, Source Code Analysis, and Byte Code Compilation UseR! 2004 Namespaces, Source Code Analysis, and Byte Code Compilation UseR! 2004 Hiding Internal Functions Name Spaces for Packages Starting with 1.7.0 a package can have Some useful programming guidelines: a name space: • Build more complex functions from simpler ones. • Only explicitly exported variables are • Create and (re)use functional building blocks. visible when attached or imported. • A function too large to fit in an editor window may be too • Variables needed from other packages complex. can be imported. Problem: All package variables are globally visible • Imported packages are loaded; may • Lots of little functions means clutter for user. -

A Hybrid Approach of Compiler and Interpreter Achal Aggarwal, Dr

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 6, June-2014 1022 ISSN 2229-5518 A Hybrid Approach of Compiler and Interpreter Achal Aggarwal, Dr. Sunil K. Singh, Shubham Jain Abstract— This paper essays the basic understanding of compiler and interpreter and identifies the need of compiler for interpreted languages. It also examines some of the recent developments in the proposed research. Almost all practical programs today are written in higher-level languages or assembly language, and translated to executable machine code by a compiler and/or assembler and linker. Most of the interpreted languages are in demand due to their simplicity but due to lack of optimization, they require comparatively large amount of time and space for execution. Also there is no method for code minimization; the code size is larger than what actually is needed due to redundancy in code especially in the name of identifiers. Index Terms— compiler, interpreter, optimization, hybrid, bandwidth-utilization, low source-code size. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION order to reduce the complexity of designing and building • Compared to machine language, the notation used by Icomputers, nearly all of these are made to execute relatively programming languages closer to the way humans simple commands (but do so very quickly). A program for a think about problems. computer must be built by combining some very simple com- • The compiler can spot some obvious programming mands into a program in what is called machine language. mistakes. Since this is a tedious and error prone process most program- • Programs written in a high-level language tend to be ming is, instead, done using a high-level programming lan- shorter than equivalent programs written in machine guage. -

Embedded System Tools Reference Manual (UG1043)

Embedded System Tools Reference Manual UG1043 (v2016.3)(v2016.1) OctoberApril 06, 5, 2016 2016 Revision History The10/05/2016: following Released table shows with Vivado the revi Designsion history Suite 2016.3 for this wi thoutdocument. changes from 2016.1. Date Version Revision 04/06/2016 2016.1 Added information about the supported processors and compilers. Added references to Zynq® UltraScale+™ MPSoC related documentation. Embedded System Tools Reference Manual www.xilinx.com Send Feedback 2 UG1043 (v2016.3)(v2016.1) October April 06, 5, 2016 2016 Table of Contents Revision History . 2 Chapter 1: Embedded System and Tools Architecture Overview Design Process Overview. 6 Vivado Design Suite Overview . 8 Software Development Kit . 9 Chapter 2: GNU Compiler Tools Overview . 12 Compiler Framework . 12 Common Compiler Usage and Options . 14 MicroBlaze Compiler Usage and Options. 29 ARM Cortex-A9 Compiler Usage and Options . 46 Other Notes . 48 Chapter 3: Xilinx System Debugger SDK System Debugger . 50 Xilinx System Debugger Command-Line Interface (XSDB) . 51 Chapter 4: Flash Memory Programming Overview . 52 Program Flash Utility . 53 Other Notes . 55 Appendix A: GNU Utilities General Purpose Utility for MicroBlaze Processors. 60 Utilities Specific to MicroBlaze Processors. 60 Other Programs and Files . 63 Appendix B: Additional Resources and Legal Notices Xilinx Resources . 64 Solution Centers. 64 Documentation Navigator and Design Hubs . 64 Embedded System Tools Reference Manual www.xilinx.com Send Feedback 3 UG1043 (v2016.3)(v2016.1) October April 06, 5, 2016 2016 References . 65 Training Resources. 65 Please Read: Important Legal Notices . 66 Embedded System Tools Reference Manual www.xilinx.com Send Feedback 4 UG1043 (v2016.3)(v2016.1) October April 06, 5, 2016 2016 Chapter 1 Embedded System and Tools Architecture Overview This guide describes the architecture of the embedded system tools and flows provided in the Xilinx® Vivado® Design Suite for developing systems based on the MicroBlaze™ embedded processor and the Cortex A9, A53 and R5 ARM processors. -

Code Verification and Run-Time Error Detection Through Abstract Interpretation

WHITE PAPER Code Verification and Run-Time Error Detection Through Abstract Interpretation A Solution to Today’s Embedded Software Testing Challenges Testing embedded systems is a difficult task, made more challenging by time pressure and the increasing complexity of embedded software. To date, there have been basically three options for detecting run-time errors in embedded applications: code reviews, static analyzers, and trial-and-error dynamic testing. Code reviews are labor-intensive and often impractical for large, complex applications. Static analyzers identify relatively few problems and, most importantly, leave most of the source code undiagnosed. Dynamic or white-box testing requires engineers to write and execute numerous test cases. When tests fail, additional time is required to find the cause of the problem through an uncertain debugging process. Abstract interpretation takes a different approach. Instead of merely detecting errors, it automatically verifies important dynamic properties of programs— including the presence or absence of run-time errors. It combines the pinpoint accuracy of code reviews with automation that enables early detection of errors and proof of code reliability. By verifying the dynamic properties of embedded applications, abstract interpretation encompasses all possible behaviors of the software and all possible variations of input data, including how software can fail. It also proves code correctness, providing strong assurance of code reliability. By using testing tools that implement abstract interpretation, businesses can reduce costs while accelerating the delivery of reliable embedded systems. This paper describes how abstract interpretation works and how you can use it to overcome the limitations of conventional techniques for testing embedded software.