Estimating Source Lines of Code from Object Code: Windows and Embedded Control Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executable Code Is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law a Retrospective Criticism of Technical and Legal Naivete in the Apple V

Executable Code is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law A retrospective criticism of technical and legal naivete in the Apple V. Franklin case Matthew M. Swann, Clark S. Turner, Ph.D., Department of Computer Science Cal Poly State University November 18, 2004 Abstract: Copyright was created by government for a purpose. Its purpose was to be an incentive to produce and disseminate new and useful knowledge to society. Source code is written to express its underlying ideas and is clearly included as a copyrightable artifact. However, since Apple v. Franklin, copyright has been extended to protect an opaque software executable that does not express its underlying ideas. Common commercial practice involves keeping the source code secret, hiding any innovative ideas expressed there, while copyrighting the executable, where the underlying ideas are not exposed. By examining copyright’s historical heritage we can determine whether software copyright for an opaque artifact upholds the bargain between authors and society as intended by our Founding Fathers. This paper first describes the origins of copyright, the nature of software, and the unique problems involved. It then determines whether current copyright protection for the opaque executable realizes the economic model underpinning copyright law. Having found the current legal interpretation insufficient to protect software without compromising its principles, we suggest new legislation which would respect the philosophy on which copyright in this nation was founded. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 THE ORIGIN OF COPYRIGHT ........................................................................... 1 The Idea is Born 1 A New Beginning 2 The Social Bargain 3 Copyright and the Constitution 4 THE BASICS OF SOFTWARE .......................................................................... -

The LLVM Instruction Set and Compilation Strategy

The LLVM Instruction Set and Compilation Strategy Chris Lattner Vikram Adve University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign lattner,vadve ¡ @cs.uiuc.edu Abstract This document introduces the LLVM compiler infrastructure and instruction set, a simple approach that enables sophisticated code transformations at link time, runtime, and in the field. It is a pragmatic approach to compilation, interfering with programmers and tools as little as possible, while still retaining extensive high-level information from source-level compilers for later stages of an application’s lifetime. We describe the LLVM instruction set, the design of the LLVM system, and some of its key components. 1 Introduction Modern programming languages and software practices aim to support more reliable, flexible, and powerful software applications, increase programmer productivity, and provide higher level semantic information to the compiler. Un- fortunately, traditional approaches to compilation either fail to extract sufficient performance from the program (by not using interprocedural analysis or profile information) or interfere with the build process substantially (by requiring build scripts to be modified for either profiling or interprocedural optimization). Furthermore, they do not support optimization either at runtime or after an application has been installed at an end-user’s site, when the most relevant information about actual usage patterns would be available. The LLVM Compilation Strategy is designed to enable effective multi-stage optimization (at compile-time, link-time, runtime, and offline) and more effective profile-driven optimization, and to do so without changes to the traditional build process or programmer intervention. LLVM (Low Level Virtual Machine) is a compilation strategy that uses a low-level virtual instruction set with rich type information as a common code representation for all phases of compilation. -

Studying the Real World Today's Topics

Studying the real world Today's topics Free and open source software (FOSS) What is it, who uses it, history Making the most of other people's software Learning from, using, and contributing Learning about your own system Using tools to understand software without source Free and open source software Access to source code Free = freedom to use, modify, copy Some potential benefits Can build for different platforms and needs Development driven by community Different perspectives and ideas More people looking at the code for bugs/security issues Structure Volunteers, sponsored by companies Generally anyone can propose ideas and submit code Different structures in charge of what features/code gets in Free and open source software Tons of FOSS out there Nearly everything on myth Desktop applications (Firefox, Chromium, LibreOffice) Programming tools (compilers, libraries, IDEs) Servers (Apache web server, MySQL) Many companies contribute to FOSS Android core Apple Darwin Microsoft .NET A brief history of FOSS 1960s: Software distributed with hardware Source included, users could fix bugs 1970s: Start of software licensing 1974: Software is copyrightable 1975: First license for UNIX sold 1980s: Popularity of closed-source software Software valued independent of hardware Richard Stallman Started the free software movement (1983) The GNU project GNU = GNU's Not Unix An operating system with unix-like interface GNU General Public License Free software: users have access to source, can modify and redistribute Must share modifications under same -

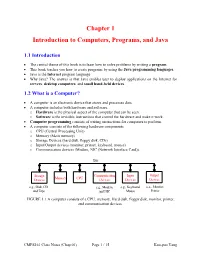

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

Some Preliminary Implications of WTO Source Code Proposala INTRODUCTION

Some preliminary implications of WTO source code proposala INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 HOW THIS IS TRIMS+ ....................................................................................................................................... 3 HOW THIS IS TRIPS+ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE TRANSFER OF SOURCE CODE .................................................................. 4 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ........................................................................................................................................... 4 AS A REMEDY FOR ANTICOMPETITIVE CONDUCT ............................................................................................................. 4 TAX LAW ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 IN GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ................................................................................................................................ 5 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE ACCESS TO SOURCE CODE ...................................................................... 5 COMPETITION LAW ................................................................................................................................................. -

Architectural Support for Scripting Languages

Architectural Support for Scripting Languages By Dibakar Gope A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Electrical and Computer Engineering) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2017 Date of final oral examination: 6/7/2017 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Mikko H. Lipasti, Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Gurindar S. Sohi, Professor, Computer Sciences Parameswaran Ramanathan, Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Jing Li, Assistant Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Aws Albarghouthi, Assistant Professor, Computer Sciences © Copyright by Dibakar Gope 2017 All Rights Reserved i This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Monoranjan Gope and Sati Gope. ii acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my parents, Sri Monoranjan Gope, and Smt. Sati Gope for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies which I believe to be the single most important contribution towards achieving my goal of receiving a Ph.D. Second, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor Prof. Mikko Lipasti for his mentorship and continuous support throughout the course of my graduate studies. I am extremely grateful to him for guiding me with such dedication and consideration and never failing to pay attention to any details of my work. His insights, encouragement, and overall optimism have been instrumental in organizing my otherwise vague ideas into some meaningful contributions in this thesis. This thesis would never have been accomplished without his technical and editorial advice. I find myself fortunate to have met and had the opportunity to work with such an all-around nice person in addition to being a great professor. -

Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK

1 From Start-ups to Scale-ups: Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK Abstract—This paper1 describes some of the challenges and research questions that target the most productive intersection opportunities when deploying static and dynamic analysis at we have yet witnessed: that between exciting, intellectually scale, drawing on the authors’ experience with the Infer and challenging science, and real-world deployment impact. Sapienz Technologies at Facebook, each of which started life as a research-led start-up that was subsequently deployed at scale, Many industrialists have perhaps tended to regard it unlikely impacting billions of people worldwide. that much academic work will prove relevant to their most The paper identifies open problems that have yet to receive pressing industrial concerns. On the other hand, it is not significant attention from the scientific community, yet which uncommon for academic and scientific researchers to believe have potential for profound real world impact, formulating these that most of the problems faced by industrialists are either as research questions that, we believe, are ripe for exploration and that would make excellent topics for research projects. boring, tedious or scientifically uninteresting. This sociological phenomenon has led to a great deal of miscommunication between the academic and industrial sectors. I. INTRODUCTION We hope that we can make a small contribution by focusing on the intersection of challenging and interesting scientific How do we transition research on static and dynamic problems with pressing industrial deployment needs. Our aim analysis techniques from the testing and verification research is to move the debate beyond relatively unhelpful observations communities to industrial practice? Many have asked this we have typically encountered in, for example, conference question, and others related to it. -

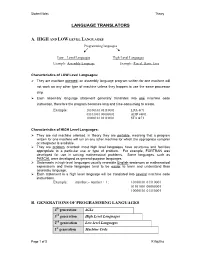

Language Translators

Student Notes Theory LANGUAGE TRANSLATORS A. HIGH AND LOW LEVEL LANGUAGES Programming languages Low – Level Languages High-Level Languages Example: Assembly Language Example: Pascal, Basic, Java Characteristics of LOW Level Languages: They are machine oriented : an assembly language program written for one machine will not work on any other type of machine unless they happen to use the same processor chip. Each assembly language statement generally translates into one machine code instruction, therefore the program becomes long and time-consuming to create. Example: 10100101 01110001 LDA &71 01101001 00000001 ADD #&01 10000101 01110001 STA &71 Characteristics of HIGH Level Languages: They are not machine oriented: in theory they are portable , meaning that a program written for one machine will run on any other machine for which the appropriate compiler or interpreter is available. They are problem oriented: most high level languages have structures and facilities appropriate to a particular use or type of problem. For example, FORTRAN was developed for use in solving mathematical problems. Some languages, such as PASCAL were developed as general-purpose languages. Statements in high-level languages usually resemble English sentences or mathematical expressions and these languages tend to be easier to learn and understand than assembly language. Each statement in a high level language will be translated into several machine code instructions. Example: number:= number + 1; 10100101 01110001 01101001 00000001 10000101 01110001 B. GENERATIONS OF PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES 4th generation 4GLs 3rd generation High Level Languages 2nd generation Low-level Languages 1st generation Machine Code Page 1 of 5 K Aquilina Student Notes Theory 1. MACHINE LANGUAGE – 1ST GENERATION In the early days of computer programming all programs had to be written in machine code. -

CDC Build System Guide

CDC Build System Guide Java™ Platform, Micro Edition Connected Device Configuration, Version 1.1.2 Foundation Profile, Version 1.1.2 Optimized Implementation Sun Microsystems, Inc. www.sun.com December 2008 Copyright © 2008 Sun Microsystems, Inc., 4150 Network Circle, Santa Clara, California 95054, U.S.A. All rights reserved. Sun Microsystems, Inc. has intellectual property rights relating to technology embodied in the product that is described in this document. In particular, and without limitation, these intellectual property rights may include one or more of the U.S. patents listed at http://www.sun.com/patents and one or more additional patents or pending patent applications in the U.S. and in other countries. U.S. Government Rights - Commercial software. Government users are subject to the Sun Microsystems, Inc. standard license agreement and applicable provisions of the FAR and its supplements. This distribution may include materials developed by third parties. Parts of the product may be derived from Berkeley BSD systems, licensed from the University of California. UNIX is a registered trademark in the U.S. and in other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, Java, Solaris and HotSpot are trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. or its subsidiaries in the United States and other countries. The Adobe logo is a registered trademark of Adobe Systems, Incorporated. Products covered by and information contained in this service manual are controlled by U.S. Export Control laws and may be subject to the export or import laws in other countries. Nuclear, missile, chemical biological weapons or nuclear maritime end uses or end users, whether direct or indirect, are strictly prohibited. -

INTRODUCTION to .NET FRAMEWORK NET Framework .NET Framework Is a Complete Environment That Allows Developers to Develop, Run, An

INTRODUCTION TO .NET FRAMEWORK NET Framework .NET Framework is a complete environment that allows developers to develop, run, and deploy the following applications: Console applications Windows Forms applications Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) applications Web applications (ASP.NET applications) Web services Windows services Service-oriented applications using Windows Communication Foundation (WCF) Workflow-enabled applications using Windows Workflow Foundation (WF) .NET Framework also enables a developer to create sharable components to be used in distributed computing architecture. NET Framework supports the object-oriented programming model for multiple languages, such as Visual Basic, Visual C#, and Visual C++. NET Framework supports multiple programming languages in a manner that allows language interoperability. This implies that each language can use the code written in some other language. The main components of .NET Framework? The following are the key components of .NET Framework: .NET Framework Class Library Common Language Runtime Dynamic Language Runtimes (DLR) Application Domains Runtime Host Common Type System Metadata and Self-Describing Components Cross-Language Interoperability .NET Framework Security Profiling Side-by-Side Execution Microsoft Intermediate Language (MSIL) The .NET Framework is shipped with compilers of all .NET programming languages to develop programs. Each .NET compiler produces an intermediate code after compiling the source code. 1 The intermediate code is common for all languages and is understandable only to .NET environment. This intermediate code is known as MSIL. IL Intermediate Language is also known as MSIL (Microsoft Intermediate Language) or CIL (Common Intermediate Language). All .NET source code is compiled to IL. IL is then converted to machine code at the point where the software is installed, or at run-time by a Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler. -

18Mca42c .Net Programming (C#)

18MCA42C .NET PROGRAMMING (C#) Introduction to .NET Framework .NET is a software framework which is designed and developed by Microsoft. The first version of .Net framework was 1.0 which came in the year 2002. It is a virtual machine for compiling and executing programs written in different languages like C#, VB.Net etc. It is used to develop Form-based applications, Web-based applications, and Web services. There is a variety of programming languages available on the .Net platform like VB.Net and C# etc.,. It is used to build applications for Windows, phone, web etc. It provides a lot of functionalities and also supports industry standards. .NET Framework supports more than 60 programming languages in which 11 programming languages are designed and developed by Microsoft. 11 Programming Languages which are designed and developed by Microsoft are: C#.NET VB.NET C++.NET J#.NET F#.NET JSCRIPT.NET WINDOWS POWERSHELL IRON RUBY IRON PYTHON C OMEGA ASML(Abstract State Machine Language) Main Components of .NET Framework 1.Common Language Runtime(CLR): CLR is the basic and Virtual Machine component of the .NET Framework. It is the run-time environment in the .NET Framework that runs the codes and helps in making the development process easier by providing the various services such as remoting, thread management, type-safety, memory management, robustness etc.. Basically, it is responsible for managing the execution of .NET programs regardless of any .NET programming language. It also helps in the management of code, as code that targets the runtime is known as the Managed Code and code doesn’t target to runtime is known as Unmanaged code. -

Using Ld the GNU Linker

Using ld The GNU linker ld version 2 January 1994 Steve Chamberlain Cygnus Support Cygnus Support [email protected], [email protected] Using LD, the GNU linker Edited by Jeffrey Osier (jeff[email protected]) Copyright c 1991, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 1998 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this manual provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this manual under the conditions for verbatim copying, provided also that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this manual into another lan- guage, under the above conditions for modified versions. Chapter 1: Overview 1 1 Overview ld combines a number of object and archive files, relocates their data and ties up symbol references. Usually the last step in compiling a program is to run ld. ld accepts Linker Command Language files written in a superset of AT&T’s Link Editor Command Language syntax, to provide explicit and total control over the linking process. This version of ld uses the general purpose BFD libraries to operate on object files. This allows ld to read, combine, and write object files in many different formats—for example, COFF or a.out. Different formats may be linked together to produce any available kind of object file. See Chapter 5 [BFD], page 47, for more information. Aside from its flexibility, the gnu linker is more helpful than other linkers in providing diagnostic information.