Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthology Drama: the Case of CBS Les Séries Anthologiques Durant L’Âge D’Or De La Télévision Américaine : Le Style Visuel De La CBS Jonah Horwitz

Document generated on 09/26/2021 8:52 a.m. Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies Visual Style in the “Golden Age” Anthology Drama: The Case of CBS Les séries anthologiques durant l’âge d’or de la télévision américaine : le style visuel de la CBS Jonah Horwitz Fictions télévisuelles : approches esthétiques Article abstract Volume 23, Number 2-3, Spring 2013 Despite the centrality of a “Golden Age” of live anthology drama to most histories of American television, the aesthetics of this format are widely URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1015184ar misunderstood. The anthology drama has been assumed by scholars to be DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1015184ar consonant with a critical discourse that valued realism, intimacy and an unremarkable, self-effacing, functional style—or perhaps even an “anti-style.” See table of contents A close analysis of non-canonical episodes of anthology drama, however, reveals a distinctive style based on long takes, mobile framing and staging in depth. One variation of this style, associated with the CBS network, flaunted a virtuosic use of ensemble staging, moving camera and attention-grabbing Publisher(s) pictorial effects. The author examines several episodes in detail, demonstrating Cinémas how the techniques associated with the CBS style can serve expressive and decorative functions. The sources of this style include the technological limitations of live-television production, networks’ broader aesthetic goals, the ISSN seminal producer Worthington Miner and contemporaneous American 1181-6945 (print) cinematic styles. 1705-6500 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Horwitz, J. (2013). Visual Style in the “Golden Age” Anthology Drama: The Case of CBS. -

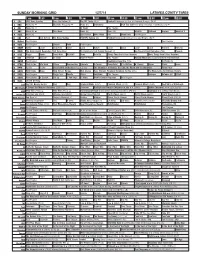

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

For Immediate Release for Immediate

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Renée Littleton/Lauren McMillen [email protected], 202-600-4055 December 15, 2020 For additional information, visit: arenastage.org/2021winterclasses ARENA STAGE ANNOUNCES NEW VIRTUAL CLASSES FOR WINTER SEASON *** Arena’s virtual series expands with family creativity workshops, classes for theater lovers, masterclasses and Voices of Now Mead Ensemble *** (Washington, D.C.) Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater announces its lineup of Winter classes featuring classes catered to families, theater lovers, students, adults and emerging theater artists. The Voices of Now Mead Ensemble for young artists will begin this winter, meeting virtually to contribute to a new original film. Just in time for the holidays, this robust line of programming has something for everyone and makes the perfect unique gift for the theater lover in your family. “We are finding that people of all ages are responding with joy and energy to our virtual classes. There are so many ways to be engaged in these programs — whether you are a theater lover or a theater practitioner, there is something for you,” shares Director of Community Engagement and Senior Artistic Advisor Anita Maynard-Losh. Arena is excited to debut two new categories of classes: Family Creativity Workshops and Classes for Theater Lovers. Family Creativity Workshops are designed to connect family members through the means of theatrical games, visual art and imagination. These classes are led by Arena’s Director of Education, Ashley Forman and friends. These exhilarating classes are the perfect opportunity for families to engage and explore creative expression and collaboration. -

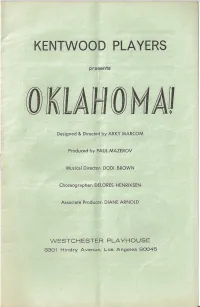

Program Design Paul Mazerov Program Coordinator

KENTWOOD PLAYERS presents Designed & Directed by ARKY MARCOM Produced by PAUL MAZEROV Musical Director: 0001, BROWN Choreographer: DELORESHENRIKSEN . Associate Producer: DIANE ARNOLD WESTCHESTER PLAYHOUSE 8301 Hindry Avenue, Los Angeles 90045 COMING ATTRACTIONS ... ~977 NOV. 11 to DEC. 17, "DIAL M FOR MURDER" - Exciting mystery by FREDERICK KNOTT. "Quiet in style but'tingling with excitement OKLAHOMA! underneath." - N.Y. Times. Director: Max Stormes. Casting: Sept. Music by: RICHARD RODGERS Book & Lyrics by: OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN II 12·13,8:00 p.m. Producer: Chris David-Belyea. Based on LYNN RIGG'S "GREEN GROWS THE LILACS" As Originally Produced by: THE THEATRE GUILD. COMING ATTRACTIONS ... ~978 SPECIAL PERMISSION OF THE RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN MUSIC LIBRARY JAN. 20·FEB. 25, "BUTTERFLIES ARE FREE." By LEONARD GERSHE. "Funny when it means to be. sentimental when it is so CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE inclined, and heart warming." NN. Daily News. Director: C. Clarke Bell. f~B~~:~~;~::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::~'i-~~~~1:~~:~5 MAR. 17·APRIL 22, "ALL THE WAY HOME." By TAD MOSEL. This IKE SKIDMORE . Norman Jay Goldman portrait of early 20th Century American life won both the Pulitzer ~~N\-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_~~-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-=:':': -.-_-_-_.-:_-.'-_-_-:~~--D~-V~a~:_tl~:~s~1~-_~-_-_~~-_-_-_-_~-_-_-_-_-_-_- Prize and Critics' Circie Award. Director: Charles Briles. WILL PARKER Peter von Ehren ro~ JUD FRY __Lawrence Ma rrlll ADO ANNIE CARNES ' Jama Tege er SPECIAL GROUP RATES All HAKIM Peter M. Eberhardt GERTIE CUMMMINGS Molly Bea Tweten Kentwood Players offers your group or organization an attractive way to arrange a desirable social event, or to plan a fund-ralsing project for any worthy cause. -

GORE VIDAL the United States of Amnesia

Amnesia Productions Presents GORE VIDAL The United States of Amnesia Film info: http://www.tribecafilm.com/filmguide/513a8382c07f5d4713000294-gore-vidal-the-united-sta U.S., 2013 89 minutes / Color / HD World Premiere - 2013 Tribeca Film Festival, Spotlight Section Screening: Thursday 4/18/2013 8:30pm - 1st Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/19/2013 12:15pm – P&I Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 6 Saturday 4/20/2013 2:30pm - 2nd Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/26/2013 5:30pm - 3rd Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 4 Publicity Contact Sales Contact Matt Johnstone Publicity Preferred Content Matt Johnstone Kevin Iwashina 323 938-7880 c. office +1 323 7829193 [email protected] mobile +1 310 993 7465 [email protected] LOG LINE Anchored by intimate, one-on-one interviews with the man himself, GORE VIDAL: THE UNITED STATS OF AMNESIA is a fascinating and wholly entertaining tribute to the iconic Gore Vidal. Commentary by those who knew him best—including filmmaker/nephew Burr Steers and the late Christopher Hitchens—blends with footage from Vidal’s legendary on-air career to remind us why he will forever stand as one of the most brilliant and fearless critics of our time. SYNOPSIS No twentieth-century figure has had a more profound effect on the worlds of literature, film, politics, historical debate, and the culture wars than Gore Vidal. Anchored by intimate one-on-one interviews with the man himself, Nicholas Wrathall’s new documentary is a fascinating and wholly entertaining portrait of the last lion of the age of American liberalism. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Radio City Playhouse

RADIO CITY PLAYHOUSE http://web.archive.org/web/20071215125232/http://www.otr.com/radio_city_playhouse.htm RADIO CITY PLAYHOUSE Official Log Based Upon Records from the Library of Congress Researched and Created by Jim Widner September 11, 2001 RADIO CITY PLAYHOUSE premiered over NBC on July 3rd, 1949 as a half-hour dramatic program representing a different drama on each broadcast. The dramas chosen, according to NBC, were because they were considered “good drama” regardless of the name of the author, the fame of the play, etc. In many instances, original radio plays were used on the series. Director of production and author of some of the original radio plays was Harry W. Junkin. The cast varied according to the script needs but New York radio actors and actresses were used, some of them experienced and others chosen from the best in radio acting newcomers. The overall production for the series was under the supervision of Richard McDonagh, NBC Script Manager. Musical bridges were by Roy Shields and his Orchestra. The announcer was Robert Warren. Series One: July 3, 1948 to September 25, 1948. Broadcast Saturdays from 10:00 – 10:30 pm EST July 3, 1948 Premiere “Long Distance” Writer: Harry W. Junkin. A drama of suspense in which a young wife has thirty minutes to get through a long distance telephone call that will save her husband from the electric chair. Note: Script was originally written for the NBC series The Chase. Cast: Jan Miner July 10, 1948 “Ground Floor Window” Writer: Ernest Kinoy. A boy with cerebral palsy spends twenty-three years of his life just sitting at a window watching the world go by before other boys realize what it meant to be just an “onlooker.” Cast: Bill Redfield (Danny) Broadcast moves to Saturdays from 10:30 – 11:00 pm EST July 17, 1948 “Of Unsound Mind” Writer: Harry W. -

THE WESTFIELD LEADER 30-33 Degrees

o o o X co ^a cr: < ia O - j E-i Today's weather: rain developing by evening. high 45-48 degrees, low THE WESTFIELD LEADER 30-33 degrees. ITte Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper In Union County Second Clasa Postage Paid Published EIGHTY-FOURTH YEAR—-No. 32 at Weatfleld. N. J. WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY. MARCH 21, 1974 very Thurat 26 Pases—15 Cents Resident Named County Dems Registration Set County Group Back Levin For New.Fool INames School Board Appoints Director of State Division For Congress LD. Cards Mrs. Allen •TKENTON - Thomas A. mercial and residential The evening times for Mrs. Sally S. Allen, New Superintendent Kelly, of Westfield a North development projects in the The Union County validating cards for the recently re-elected to the Jersey banking executive, North Jersey area serviced Democratic Committee has Westfield Memorial Pool's Hoard of Educat ion here has Dr. Laurence F. Greene, who has been involved in by the Jersey City-based chosen Adam K, Levin of new season and for issuing Dr. William R. Manning, bank. Westfield to run . for been elected president of the an educator who began as a economic and industrial new photos will be Tuesdays I'nion County (educational appointed to the superin- development programs in Prior to joining First Congress in the 12th. classroom teacher 28 years tendancy at the Board's from 7 to 9 p.m. on March 20, Services Commission ago and has served as a New Jersey for the past 14 Jersey National he served congressional district, April «, 23, May 14, 2IS. -

Scripts and Set Plans for the Television Series the Defenders, 1962-1965 PASC.0129

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1b69q2wz No online items Scripts and Set Plans for the Television Series The Defenders, 1962-1965 PASC.0129 Finding aid prepared by UCLA staff, 2004 UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2020 November 2 Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Scripts and Set Plans for the PASC.0129 1 Television Series The Defenders, 1962-1965 PASC.0129 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: The Defenders scripts and set plans Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0129 Physical Description: 3 Linear Feet(7 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1962-1965 Abstract: The Defenders was televised 1961 to 1965. The series featured E.G. Marshall and Robert Reed as a father-son team of defense attorneys. The program established a model for social-issue type television series that were created in the early sixties. The collection consists of annotated scripts from January 1962 to March 1965. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Paddy Chayefsky on the Craft of Writing (Excerpts), 8 John Joseph Brady

Audience Guide Written and Compiled by Jack Marshall September 17 – October 16, 2010 Gunston TheatreTwo About The American Century Theater The American Century Theater was founded in 1994. We are a professional company dedicated to presenting great, important, and neglected American plays of the Twentieth Century… what Henry Luce called “the American Century.” The company‘s mission is one of rediscovery, enlightenment, and perspective, not nostalgia or preservation. Americans must not lose the extraordinary vision and wisdom of past playwrights, nor can we afford to surrender our moorings to our shared cultural heritage. Our mission is also driven by a conviction that communities need theater, and theater needs audiences. To those ends, this company is committed to producing plays that challenge and move all Americans, of all ages, origins and points of view. In particular, we strive to create theatrical experiences that entire families can watch, enjoy, and discuss long afterward. These study guides are part of our effort to enhance the appreciation of these works, so rich in history, content, and grist for debate. The American Century Theater is a 501(c)(3) professional nonprofit theater company dedicated to producing significant 20th Century American plays and musicals at risk of being forgotten. TACT is funded in part by the Arlington County Cultural Affairs Division of the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Resources and the Arlington Commission for the Arts. This arts event is made possible in part by the Virginia Commission for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as by many generous donors. -

Member/Audience Play Suggestions 2012-13

CURTAIN PLAYERS 2012-2013 plays suggested by patrons/members Title Author A Poetry Reading (Love Poetry for Valentines Day) Agnes of God All My Sons (by 3 people) Arthur Miller All The Way Home Tad Mosel Angel Street Anything by Pat Cook Pat Cook Apartment 3A Jeff Daniels Arcadia Tom Stoppard As Bees in Honey Drown Assassins Baby With The Bathwater (by 2 people) Christopher Durang Beyond Therapy Christopher Durang Bleacher Bums Blythe Spirit (by 2 people) Noel Coward Butterscotch Cash on Delivery Close Ties Crimes of the Heart Beth Henley Da Hugh Leonard Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (by 2 people) Jeffrey Hatcher Driving Miss Daisy Equus Peter Shaffer Farragut North Beau Willimon Frankie and Johnny in the Claire De Lune Terrence McNally God's Country Happy Birthday, Wanda June Kurt Vonnegut I Never Saw Another Butterfly Impressionism Michael Jacobs Laramie Project Leaving Iowa Tim Clue/Spike Manton Lettice and Lovage (by 2 people) Lombardi Eric Simonson LuAnn Hampton Laverty Oberlander Mr and Mrs Fitch Douglas Carter Beane 1 Night Mother No Exit Sartre Picnic William Inge Prelude to A Kiss (by 2 people) Craig Lucas Proof Red John Logan Ridiculous Fraud Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (by 2 people) Tom Stoppard Sabrina Fair Samuel Taylor Second Samuel Pamela Parker She Loves Me Sheer Madness Side Man Warren Leight Sin Sister Mary Ignatius/Actor's Nightmare Christopher Durang Smoke on the Mountain (by 3 people) That Championship Season Jason Miller The 1940's Radio Hour Walton Jones The Caine Mutiny Court Martial The Cinderella Waltz The Country Girl Clifford Odets The Heidi Chronicles The Increased Difficulty of Concentration Vaclav Havel The Little Foxes Lillian Hellman The Man Who Came To Dinner Kaufman and Hart The Miser Moliere The Normal Heart Larry Kramer The Odd Couple Neil Simon The Passion of Dracula The Royal Family Kaufman and Ferber The Shape of Things LaBute The Substance of Fire Jon Robin Baitz The Tempest Shakespeare The Woolgatherer Three Days of Rain Richard Greenberg Tobacco Road While The Lights Were Out Wit 2 3 . -

Citizen Kane – Page 1 Th 75 ANNIVERSARY COLLECTOR’S EDITION INCLUDING EXTRAORDINARY COLLECTABLES

Citizen Kane – Page 1 th 75 ANNIVERSARY COLLECTOR’S EDITION INCLUDING EXTRAORDINARY COLLECTABLES “A film that gets better with each renewed acquaintance” Time Out CITIZEN KANE Starring Orson Welles th TM 75 Anniversary Edition Bluray out 2nd May Includes special commentaries, interviews and more! On May 2nd 2016, Warner Bros. Home Entertainment (WBHE) will release the 75th Anniversary BlurayTM edition of the Orson Welles classic CITIZEN KANE. This new 4k restoration BlurayTM comes with a set of collectables including; 5 x One Sheet/ Lobby Card reproductions, a 48page book with photos, storyboards and behind the scenes info, a 20page 1941 souvenir programme reproduction and 10 x production memos and correspondence. The Oscar®*winning film, directed, written by and starring Orson Welles, is considered to be one of the finest achievements in cinema and last year topped the BBC Culture poll of the 100 Greatest American Films. Welles was only 25 years old when he made this, his debut film, a gripping drama which would cement his reputation as one of Hollywood’s most influential directors and stars. *1942 Academy Awards Best Writing, Original Screenplay Herman J. Mankiewicz, Orson Welles Citizen Kane – Page 2 With a cast including Joseph Cotten, Agnes Moorehead and Everett Sloane, Oscarnominated camerawork by Gregg Toland (Wuthering Heights, The Grapes of Wrath), and featuring a debut score by Bernard Herrmann (Psycho, Taxi Driver) this is a film that Time Out says “still amazes and delights”. ABOUT THE FILM 1940. Alone at his fantastic estate known as Xanadu, 70yearold Charles Foster Kane dies, uttering only the single word Rosebud.