Post‐Operative Nausea & Vomiting ‐ Use of Anti‐Emetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adverse Reactions to Hallucinogenic Drugs. 1Rnstttutton National Test

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 034 696 SE 007 743 AUTROP Meyer, Roger E. , Fd. TITLE Adverse Reactions to Hallucinogenic Drugs. 1rNSTTTUTTON National Test. of Mental Health (DHEW), Bethesda, Md. PUB DATP Sep 67 NOTE 118p.; Conference held at the National Institute of Mental Health, Chevy Chase, Maryland, September 29, 1967 AVATLABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. 20402 ($1.25). FDPS PRICE FDPS Price MFc0.50 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCPTPTOPS Conference Reports, *Drug Abuse, Health Education, *Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, *Medical Research, *Mental Health IDENTIFIEPS Hallucinogenic Drugs ABSTPACT This reports a conference of psychologists, psychiatrists, geneticists and others concerned with the biological and psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide and other hallucinogenic drugs. Clinical data are presented on adverse drug reactions. The difficulty of determining the causes of adverse reactions is discussed, as are different methods of therapy. Data are also presented on the psychological and physiolcgical effects of L.S.D. given as a treatment under controlled medical conditions. Possible genetic effects of L.S.D. and other drugs are discussed on the basis of data from laboratory animals and humans. Also discussed are needs for futher research. The necessity to aviod scare techniques in disseminating information about drugs is emphasized. An aprentlix includes seven background papers reprinted from professional journals, and a bibliography of current articles on the possible genetic effects of drugs. (EB) National Clearinghouse for Mental Health Information VA-w. Alb alb !bAm I.S. MOMS Of NAM MON tMAN IONE Of NMI 105 NUNN NU IN WINES UAWAS RCM NIN 01 NUN N ONMININI 01011110 0. -

Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group Guidelines on the Use of Antiemetics Author(S): Dr Annette Edwards (Chai

Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group Guidelines on the use of Antiemetics Author(s): Dr Annette Edwards (Chair) and Deborah Royle on behalf of the Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group Overall objective : To provide guidance on the evidence for the use of antiemetics in specialist palliative care. Search Strategy: Search strategy: Medline, Embase and Cinahl databases were searched using the words nausea, vomit$, emesis, antiemetic and drug name. Review Date: March 2008 Competing interests: None declared Disclaimer: These guidelines are the property of the Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group. They are intended to be used by qualified, specialist palliative care professionals as an information resource. They should be used in the clinical context of each individual patient’s needs. The clinical guidelines group takes no responsibility for any consequences of any actions taken as a result of using these guidelines. Contact Details: Dr Annette Edwards, Macmillan Consultant in Palliative Medicine, Department of Palliative Medicine, Pinderfields General Hospital, Aberford Road, Wakefield, WF1 4DG Tel: 01924 212290 E-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction: Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. A careful history, examination and appropriate investigations may help to infer the pathophysiological mechanism involved. Where possible and clinically appropriate aetiological factors should be corrected. Antiemetics are chosen based on the likely mechanism and the neurotransmitters involved in the emetic pathway. However, a recent systematic review has highlighted that evidence for the management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer is sparse. (Glare 2004) The following drug and non-drug treatments were reviewed to assess the strength of evidence for their use as antiemetics with particular emphasis on their use in the palliative care population. -

The Use of Cyclizine in Patients Receiving Parenteral Nutrition

DRAFT - The use of cyclizine in patients receiving parenteral nutrition Jeremy Nightingale, Uchu Meade, Gavin Leahy and the BIFA committee Cyclizine is a piperazine derivative that was discovered in 1947 while researching new antihistamine drugs (H1 blockers) and was first sold 1965. It is marketed for the treatment or prevention of nausea, vomiting, and labyrinthine disorders including vertigo and motion sickness. This includes nausea after a general anaesthetic and that caused by opioid use. In the United Kingdom the oral formulation is classified as a Pharmacy (P) medicine and can be sold from a registered pharmacy premises by or under the supervision of a pharmacist. The intravenous formulation is classified as a Prescription Only Medicine (POM). There is increasing recognition that the intravenous formulation of cyclizine may cause euphoria and dependence (addiction); these side effects may not be reported by patients and be under recognised by healthcare professionals. It has many associated problems when used by patients receiving long-term parenteral nutrition. This position paper highlights the risks associated with its long-term intravenous use. Actions/pharmacology (1) Cyclizine has both anti-histamine (H1) and anti-cholinergic (anti-muscarinic M1) effects. It is a class 1 drug in the biopharmaceutical classification (high permeability and solubility) with a peak plasma concentration of about 70 ng/ ml reached approximately 2 hours after oral ingestion, as measured in healthy adult patients. Its quoted elimination (biological) half-life is 20 hours when given orally (1) and 13 hours when given intravenously (2). Cyclizine is metabolised to its N-demethylated derivative, norcyclizine, which has little anti-histaminic (H1) activity compared to cyclizine. -

Motion Sickness Traveler Summary Key Points Motion Sickness Consists of a Group of Signs and Symptoms That Develop in Response to Real Or Perceived Motion

Motion Sickness Traveler Summary Key Points Motion sickness consists of a group of signs and symptoms that develop in response to real or perceived motion. Symptoms include dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Prevention includes: Eating light meals Avoiding alcohol Sitting in the front seat of a car, over the wings on an airplane, or mid-deck on ships and facing forward in buses and trains Avoiding tasks requiring a close focus (e.g., reading) Using over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription medication OTC medications include: Dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, cyclizine, or meclizine: take 1 hour before departure and continue during the trip. These medications can cause sedation; do not mix with alcohol. Read labels carefully. Check for cautions regarding use in certain conditions. Prescription medications include: Scopolamine patches: place behind the ear; change every 3 days; apply 8 hours before the first incidence of rough weather or rough roads. Dry mouth and dry eyes may result. Patches do not work if cut in half. More than 1 patch should never be applied; hallucinations or psychosis may result. Strong sedatives (such as promethazine or prochlorperazine): take orally or by suppository after onset of severe symptoms, but anticipate sleep for a number of hours. A cruise medical clinic may administer injectable promethazine if absolutely necessary. Introduction The human body has a delicate system of equilibrium that relies on fluids in the inner ear, visual sensors, and other physical input to maintain a sense of balance. When incoming signals are in conflict—for example, when the body is at rest yet the eyes sense movement—this system is disturbed, causing the symptoms of motion sickness. -

On the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Cosmetic Products (76/768/EEC )

27 . 9 . 76 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 262/169 COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 27 July 1976 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to cosmetic products (76/768/EEC ) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, regards the composition, labelling and packaging of cosmetic products ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the Euro pean Economic Community, and in particular Whereas this Directive relates only to cosmetic prod Article 100 thereof, ucts and not to pharmaceutical specialities and medicinal products ; whereas for this purpose it is necessary to define the scope of the Directive by Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, delimiting the field of cosmetics from that of phar maceuticals ; whereas this delimitation follows in particular from the detailed definition of cosmetic Having regard to the opinion of the European Parlia products, which refers both to their areas of appli ment ( 1 ), cation and to the purposes of their use; whereas this Directive is not applicable to the products that fall Having regard to the opinion of the Economic and under the definition of cosmetic product but are Social Committee (2 ), exclusively intended to protect from disease; whereas, moreover, it is advisable to specify that certain prod ucts come under this definition, whilst products Whereas the provisions laid down by law, regulation containing substances or preparations intended to be or administrative action in force in the Member ingested, inhaled, injected or implanted in the human States -

Medicines Classification Committee

Medicines Classification Committee Meeting date 1 May 2017 58th Meeting Title Reclassification of Sedating Antihistamines Medsafe Pharmacovigilance Submitted by Paper type For decision Team Proposal for The Medicines Adverse Reactions Committee (MARC) recommended that the reclassification to committee consider reclassifying sedating antihistamines to prescription prescription medicines when used in children under 6 years of age for the treatment of medicine for some nausea and vomiting and travel sickness [exact wording to be determined by indications the committee]. Reason for The purpose of this document is to provide the committee with an overview submission of the information provided to the MARC about safety concerns associated with sedating antihistamines and reasons for recommendations. Associated March 2013 Children and Sedating Antihistamines Prescriber Update articles February 2010 Cough and cold medicines clarification – antihistamines Medsafe website Safety information: Use of cough and cold medicines in children – new advice Medicines for Alimemazine Diphenhydramine consideration Brompheniramine Doxylamine Chlorpheniramine Meclozine Cyclizine Promethazine Dexchlorpheniramine New Zealand Some oral sedating antihistamines available without exposure to a prescription (pharmacist-only and pharmacy only), sedating therefore usage data is not easily available. antihistamines Table of Contents 1.0 PURPOSE ...................................................................................................................................... -

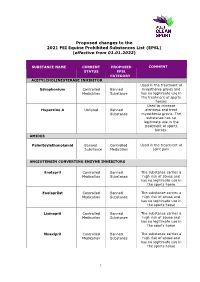

Proposed Changes to the 2021 FEI Equine Prohibited Substances List (EPSL) (Effective from 01.01.2022)

Proposed changes to the 2021 FEI Equine Prohibited Substances List (EPSL) (effective from 01.01.2022) SUBSTANCE NAME CURRENT PROPOSED COMMENT STATUS EPSL CATEGORY ACETYLCHOLINESTERASE INHIBITOR Used in the treatment of Edrophonium Controlled Banned myasthenia gravis and Medication Substance has no legitimate use in the treatment of sports horses Used to increase Huperzine A Unlisted Banned alertness and treat Substance myasthenia gravis. The substance has no legitimate use in the treatment of sports horses. AMIDES Palmitoylethanolamid Banned Controlled Used in the treatment of Substance Medication joint pain ANGIOTENSIN CONVERTING ENZYME INHIBITORS Enalapril Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse Enalaprilat Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse Lisinopril Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse Moexipril Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse 1 Perindoprilat Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse ANTIHISTAMINES Antazoline Controlled Banned The substance has no Medication Substance legitimate use in the sports horse Azatadine Controlled Banned The substance has Medication Substance sedative effects -

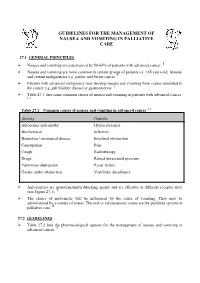

Guidelines for the Management of Nausea and Vomiting in Palliative Care

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF NAUSEA AND VOMITING IN PALLIATIVE CARE 27.1 GENERAL PRINCIPLES Nausea and vomiting are experienced by 50-60% of patients with advanced cancer. 1 Nausea and vomiting are more common in certain groups of patients i.e. <65 years old, females and certain malignancies e.g. gastric and breast cancer. 1 Patients with advanced malignancy may develop nausea and vomiting from causes unrelated to the cancer e.g. gall bladder disease or gastroenteritis. 1 Table 27.1 lists some common causes of nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer. 1, 2 1, 2 Table 27.1 Common causes of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer Anxiety Gastritis Autonomic neuropathy Hypercalcaemia Biochemical Infection Brainstem / meningeal disease Intestinal obstruction Constipation Pain Cough Radiotherapy Drugs Raised intracranial pressure Functional obstruction Renal failure Gastric outlet obstruction Vestibular disturbance Anti-emetics are neurotransmitter-blocking agents and are effective at different receptor sites (see Figure 27.1). 3 The choice of anti-emetic will be influenced by the cause of vomiting. They may be administered by a variety of routes. The oral or subcutaneous routes are the preferred options in palliative care. 4 27.2 GUIDELINES Table 27.2 lists the pharmacological options for the management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. 3 Table 27.2 Pharmacological options for the management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 [Level 4] Drug name Type of drug Indication for Oral dose Parenteral dose Parenteral dose Notes use (subcutaneously over (subcutaneous stat 24 hours via a syringe doses) driver) Cyclizine Antihistamine Central causes. -

The Management of Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy and Hyperemesis Gravidarum

The Management of Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy and Hyperemesis Gravidarum Green-top Guideline No. 69 June 2016 The Management of Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy and Hyperemesis Gravidarum This is the first edition of this guideline. Executive summary of recommendations Diagnosis of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) and hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) How is NVP diagnosed? NVP should only be diagnosed when onset is in the first trimester of pregnancy and other causes of D nausea and vomiting have been excluded. How is HG diagnosed? HG can be diagnosed when there is protracted NVP with the triad of more than 5% prepregnancy D weight loss, dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. How can the severity of NVP be classified? An objective and validated index of nausea and vomiting such as the Pregnancy-Unique C Quantification of Emesis (PUQE) score can be used to classify the severity of NVP. What initial clinical assessment and baseline investigations should be done before deciding on treatment? Clinicians should be aware of the features in history, examination and investigation that allow NVP and HG to be assessed and diagnosed and for their severity to be monitored. P What are the differential diagnoses? Other pathological causes should be excluded by clinical history, focused examination and investigations. P What is the initial management of NVP and HG? How should the woman be managed? Women with mild NVP should be managed in the community with antiemetics. D Ambulatory daycare management should be used for suitable patients when community/primary C care measures have failed and where the PUQE score is less than 13. -

Safety and Efficacy of Doxylamine Succinate 10Mg with Pyridoxine Hydrochloride 10Gs (Diclectin) for Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy (N.V.P)

Safety and Efficacy of Doxylamine Succinate 10mg with Pyridoxine Hydrochloride 10gs (Diclectin) for Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy (N.V.P) 1. Careful questioning of the patient, early in pregnancy, about the frequency and intensity of the symptoms of nausea and vomiting allows the practitioner to intervene with diet and lifestyle adjustments, as well as medication with the aim of preventing hyperemesis gravidarum. Doxylamine Succinate 10mg, in combination with Pyridoxine Hcl 10mg (Diclectin), were approved for use in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy by the Health Protection Branch of Health and Welfare Canada in 1990. To date, this formulation is the only anti-nauseant approved for such use. Bendectin (Diclectin) which was withdrawn from the market in 1983 in the USA after several unsuccessful lawsuits against it. Despite the most vigorous testing of any drug in pregnancy, no evidence of teratogenicity has been found. Multiple studies have reviewed Debendox (Bendectin, Diclectin) and concluded that the drug is a safe effective treatment for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and that there is no evidence that it is a teratogen. Doxylamine Succinate in combination with Pyridoxine Hcl 10mg (Diclectin) is a delayed release tablet. It is recommended that they start with two tablets at night before bed. If symptoms are not relieved, one tablet in the morning and another mid-afternoon can be added. The dosing regime can be tailored to fit each woman’s peak of symptoms. It is recommended that all health professionals should question women early in their pregnancies about the presence of these symptoms, and offer intervention, with advice about diet, lifestyle adjustment and medical treatment. -

The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland

Autumn 2016 The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland Guidelines on the Prevention of Post-operative Vomiting in Children Contributing Authors: Simon Martin David Baines Helen Holtby Alison S Carr Guidelines on the Prevention of Postoperative Vomiting in Children Members of the 2016 Guidelines Revision Group: Dr Simon Martin Consultant Paediatric Anaesthetist Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust Derriford Hospital Plymouth Professor Alison S Carr Consultant Paediatric Anaesthetist Head of Clinical Education & Professor College of Medicine Qatar University PO Box 2713 Doha, Qatar Dr David Baines Clinical Associate Professor Head, Department of Anaesthesia The Children's Hospital at Westmead NSW Australia Dr Helen Holtby Staff Anesthesiologist Division of Cardiac Anesthesia Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine SickKids Hospital, Toronto Additional Contributing Authors of 2009 Guideline Simon Courtman Neil Morton Scott Jacobson Liam Brennan Per-Arne Lönnqvist Jackie Pope 3 Contents Page No. Key to evidence statements and grades of recommendation 4 Introduction 5 Remit of the guideline Glossary 7 1. Identifying children at high risk of postoperative vomiting (POV) 8 A. Patient factors 8 Age, history of POV, motion sickness, gender, preoperative anxiety, smoking B. Surgical Factors 10 Duration of surgery, type of surgery C. Anaesthetic Factors 12 Nitrous oxide, volatile agents, peri-operative opioids, anticholinesterases, peri-operative fluids 2. Pharmacological treatment of POV in children A. Anti-emetics for prevention & reduction of POV in children 14 Single Agents: 14 5HT3 Antagonists, Dexamethasone, Metoclopramide, Prochlorperazine, Cyclizine, Dimenhydrinate Combination Therapy: 24 Ondansetron and dexamethasone, Ondansetron and other combination anti-emetic therapy, Tropisetron B. Anti-emetics for treating established POV in children 25 3. -

Doxylamine and Pyridoxine New Medicine Assessment

New Medicine Assessment Doxylamine succinate and pyridoxine hydrochloride 10 mg/10 mg gastro-resistant tablets (Xonvea®) for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in women who do not respond to conservative management. Recommendation: Green Appropriate for initiation and ongoing prescribing in both primary and secondary care. Summary of supporting evidence • The results of the DESI study appear to show sufficient evidence to support the clinical contributions of each of the monocomponents in the fixed dose combination • In the DIC-301 study a greater improvement of 0.8-11 PUQE units for Xonvea compared to placebo was demonstrated for days 3, 4, 5, 10 and 15. These statistically significant differences, based on the PUQE scale, represent improvements that are clinically meaningful for pregnant women suffering from NVP. • The product was previously available but was withdrawn from the market in 1983 due to litigation burdens and adverse publicity affecting the product. • The current formulation has been on the Canadian market since 1979 and on the US market since 2013 Details of Review Name of medicine (generic & brand name): Doxylamine succinate and pyridoxine hydrochloride (Xonvea®) Strengths and forms: 10 mg/10 mg gastro-resistant tablets Dose and administration: The recommended starting dose is two tablets at bedtime (Day 1). If this dose adequately controls symptoms the next day, the patient can continue taking two tablets at bedtime. However, if symptoms persist into the afternoon of Day 2, the patient should continue the usual dose of two tablets at bedtime (Day 2) and on Day 3 take three tablets (one tablet in the morning and two tablets at bedtime).