UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory 2017

DISTRICT DIRECTORY / PATHANAMTHITTA / 2017 INDEX Kerala RajBhavan……..........…………………………….7 Chief Minister & Ministers………………..........………7-9 Speaker &Deputy Speaker…………………….................9 M.P…………………………………………..............……….10 MLA……………………………………….....................10-11 District Panchayat………….........................................…11 Collectorate………………..........................................11-12 Devaswom Board…………….............................................12 Sabarimala………...............................................…......12-16 Agriculture………….....…...........................……….......16-17 Animal Husbandry……….......………………....................18 Audit……………………………………….............…..…….19 Banks (Commercial)……………..................………...19-21 Block Panchayat……………………………..........……….21 BSNL…………………………………………….........……..21 Civil Supplies……………………………...............……….22 Co-Operation…………………………………..............…..22 Courts………………………………….....................……….22 Culture………………………………........................………24 Dairy Development…………………………..........………24 Defence……………………………………….............…....24 Development Corporations………………………...……24 Drugs Control……………………………………..........…24 Economics&Statistics……………………....................….24 Education……………………………................………25-26 Electrical Inspectorate…………………………...........….26 Employment Exchange…………………………...............26 Excise…………………………………………….............….26 Fire&Rescue Services…………………………........……27 Fisheries………………………………………................….27 Food Safety………………………………............…………27 -

States Symbols State/ Union Territories Motto Song Animal / Aquatic

States Symbols State/ Animal / Foundation Butterfly / Motto Song Bird Fish Flower Fruit Tree Union territories Aquatic Animal day Reptile Maa Telugu Rose-ringed Snakehead Blackbuck Common Mango సతవ జయే Thalliki parakeet Murrel Neem Andhra Pradesh (Antilope jasmine (Mangifera indica) 1 November Satyameva Jayate (To Our Mother (Coracias (Channa (Azadirachta indica) cervicapra) (Jasminum officinale) (Truth alone triumphs) Telugu) benghalensis) striata) सयमेव जयते Mithun Hornbill Hollong ( Dipterocarpus Arunachal Pradesh (Rhynchostylis retusa) 20 February Satyameva Jayate (Bos frontalis) (Buceros bicornis) macrocarpus) (Truth alone triumphs) Satyameva O Mur Apunar Desh Indian rhinoceros White-winged duck Foxtail orchid Hollong (Dipterocarpus Assam सयमेव जयते 2 December Jayate (Truth alone triumphs) (O My Endearing Country) (Rhinoceros unicornis) (Asarcornis scutulata) (Rhynchostylis retusa) macrocarpus) Mere Bharat Ke House Sparrow Kachnar Mango Bihar Kanth Haar Gaur (Mithun) Peepal tree (Ficus religiosa) 22 March (Passer domesticus) (Phanera variegata) (Mangifera indica) (The Garland of My India) Arpa Pairi Ke Dhar Satyameva Wild buffalo Hill myna Rhynchostylis Chhattisgarh सयमेव जयते (The Streams of Arpa Sal (Shorea robusta) 1 November (Bubalus bubalis) (Gracula religiosa) gigantea Jayate (Truth alone triumphs) and Pairi) सव भाण पयतु मा किच Coconut palm Cocos दुःखमानुयात् Ruby Throated Grey mullet/Shevtto Jasmine nucifera (State heritage tree)/ Goa Sarve bhadrāṇi paśyantu mā Gaur (Bos gaurus) Yellow Bulbul in Konkani 30 May (Plumeria rubra) -

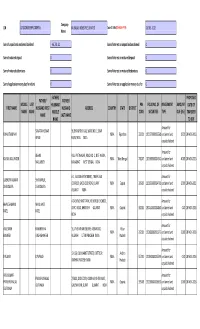

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Elephant Escapades Audience Activity Designed for 10 Years Old and Up

Elephant Escapades Audience Activity designed for 10 years old and up Goal Students will learn the differences between the African and Asian elephants, as well as, how their different adaptations help them survive in their habitats. Objective • To understand elephant adaptations • To identify the differences between African and Asian elephants Conservation Message Elephants play a major role in their habitats. They act as keystone species which means that other species depend on them and if elephants were removed from the ecosystem it would change drastically. It is important to understand these species and take efforts to encourage the preservation of African and Asian elephants and their habitats. Background Information Elephants are the largest living land animal; they can weigh between 6,000 and 12,000 pounds and stand up to 12 feet tall. There are only two species of elephants; the African Elephants and the Asian Elephant. The Asian elephant is native to parts of South and Southeast Asia. While the African elephant is native to the continent of Africa. While these two species are very different, they do share some common traits. For example, both elephant species have a trunk that can move in any direction and move heavy objects. An elephant’s trunk is a fusion, or combination, of the nose and upper lip and does not contain any bones. Their trunks have thousands of muscles and tendons that make movements precise and give the trunk amazing strength. Elephants use their trunks for snorkeling, smelling, eating, defending themselves, dusting and other activities that they perform daily. Another common feature that the two elephant species share are their feet. -

Asian Elephant, Listed As An

HUMAN ELEPHANT CONFLICT IN HOSUR FOREST DIVISION, TAMILNADU, INDIA Interim Report to Hosur Forest Division, Tamil Nadu Forest Department by N. Baskaran and P. Venkatesh ASIAN NATURE CONSERVATION FOUNDATION INNOVATION CENTRE FIRST FLOOR INDIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE BANGALORE - 560 012, INDIA SEPTEMBER 2009 1 Section Title Page No. 1. INTRODUCTION 01 2. METHODS 08 2.1 Study area 08 2.2 Human Elephant Conflict 13 2.2.1. Evaluation of conflict status 13 2.2.2. Assessment on cropping pattern 13 2.2.3. Evaluation of human–elephant conflict mitigation measures 14 2.2.4. Use of GIS and remote sensing in Human–elephant conflict 14 3 OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS 16 3.1. Status of human–elephant conflict 16 3.1.1. Crop damage by elephants 16 3.1.2. Human death by elephants 16 3.1.3. Crop damage in relation to month 18 3.1.4. Other damages caused by elephants 18 3.1.5. Spatial variation in crop damage 20 3.2. Causes of human–elephant conflict 24 3.2.1. Cropping pattern and its influence 24 3.2.2. Landscape attributes 29 3.2.3. Cattle grazing and its impact 29 3.3. Measures of conflict mitigation and their efficacy 31 4. DISCUSSION 35 5. SUMMARY 40 REFERENCES 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We thank the Tamil Nadu Forest Department especially Mr. Sundarajan IFS Chief Wildlife Warden Tamil Nadu, Mr. V. Ganeshan IFS, District Forest Officer, Hosur Forest Division for readily permitting me to carryout this work and extending all supports for this study. I also thank all the Forest Range Officers, Foresters, Forest Guards and Forest Watchers in Hosur Forest Division for their support during my filed work. -

Adavu’ Groups of Sangita Saramrta with the Present Practicing Tradition of Bharatanatyam ADITI NIGAM BATRA / 45

ISSN 2455-7250 Vol. XVII No. 1 January - March 2017 A Quarterly Journal of Indian Dance Cover Feature: Buddhist Dances of Bhutan A Quarterly Journal of Indian Dance Volume: XVII, No. 1 January-March 2017 Sahrdaya Arts Trust Hyderabad RNI No. APENG2001/04294 ISSN 2455-7250 Nartanam, founded by Kuchipudi Kala Kendra, Founders Mumbai, now owned and published by Sahrdaya G. M. Sarma Arts Trust, Hyderabad, is a quarterly which provides a forum for scholarly dialogue on a broad M. Nagabhushana Sarma range of topics concerning Indian dance. Its concerns are theoretical as well as performative. Chief Editor Textual studies, dance criticism, intellectual and Madhavi Puranam interpretative history of Indian dance traditions are its focus. It publishes performance reviews Patron and covers all major events in the field of dance in Edward R. Oakley India and notes and comments on dance studies and performances abroad. Chief Executive The opinions expressed in the articles and the Vikas Nagrare reviews are the writers’ own and do not reflect the opinions of the editorial committee. The editors and publishers of Nartanam do their best to Advisory Board verify the information published but do not take Anuradha Jonnalagadda (Scholar, Kuchipudi dancer) responsibility for the absolute accuracy of the Avinash Pasricha (Former Photo Editor, SPAN) information. C.V. Chandrasekhar (Bharatanatyam Guru, Padma Bhushan) Cover Photo: A Buddhist Monk, dancing Kedar Mishra (Poet, Scholar, Critic) Kiran Seth (Padma Shri; Founder, SPIC MACAY) Photo Courtesy: Literature of K. K. Gopalakrishnan (Critic, Scholar) Thimphu Tschechu by Bhutan Leela Venkataraman (Critic, Scholar, SNA Awardee) Communications Services, Mallika Kandali (Sattriya dancer, Scholar) [email protected] Pappu Venugopala Rao (Scholar, Former Associate D G, American Institute; Secretary, Music Academy) Photographers: Kezang Namgay, Reginald Massey (Poet, FRSA & Freeman of London) Leon Rabten, Lakey Dorji, Sunil Kothari (Scholar, Padma Shri & SNA Awardee) Lhendup Suresh K. -

Power of Talent

Black Red CharcoalGray WarmGray Power of talent “Our core corporate assets walk out every evening. It is our duty to make sure that these assets return the next morning, mentally and physically enthusiastic and energetic.” – N. R. Narayana Murthy, Chairman and Chief Mentor This Annual Report is printed on 100% recycled paper as certified by the UK-based National Association of Paper Merchants (NAPM). The paper complies with strict quality and environmental requirements and is awarded the following international eco-labels: the Nordic Swan from the Nordic Council of Ministers; the Blue Angel, the first worldwide environmental label awarded by the Jury Umweltzeichen; and the European Union Flower. Infosys Annual Report 2007-08 | 1 Eugenie Rosenthal InStep intern in 2007 Mardava Rajugopal Catch Them Young participant in 2007 Deepak Gopinath Catch Them Young participant in 2007 Connect In 2007, an impressive 66% of 350 colleges surveyed opined that our Campus Connect program has helped make their students more employable. 2 | Power of talent Black Red CharcoalGray WarmGray Development Center, Bangalore, India By 2010, the Indian IT industry will need significantly contributed to our cultural “CTY was an enriching 2.3 million software engineers, says a and intellectual diversity. In the last nine experience. The courses were NASSCOM study. The estimated shortfall years, we have had over 600 interns from conducted in an encouraging, is 22%. This shortfall is one of the key 85 premier universities such as Harvard, open atmosphere which helped reasons we think it is imperative to connect Stanford, MIT and Oxford. InStep has us think out of the box and make the academic world with the industry. -

Psyphil Celebrity Blog Covering All Uncovered Things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies List New Films List Latest Tamil Movie List Filmography

Psyphil Celebrity Blog covering all uncovered things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies list new films list latest Tamil movie list filmography Name: Vijay Date of Birth: June 22, 1974 Height: 5’7″ First movie: Naalaya Theerpu, 1992 Vijay all Tamil Movies list Movie Y Movie Name Movie Director Movies Cast e ar Naalaya 1992 S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sridevi, Keerthana Theerpu Vijay, Vijaykanth, 1993 Sendhoorapandi S.A.Chandrasekar Manorama, Yuvarani Vijay, Swathi, Sivakumar, 1994 Deva S. A. Chandrasekhar Manivannan, Manorama Vijay, Vijayakumar, - Rasigan S.A.Chandrasekhar Sanghavi Rajavin 1995 Janaki Soundar Vijay, Ajith, Indraja Parvaiyile - Vishnu S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sanghavi - Chandralekha Nambirajan Vijay, Vanitha Vijaykumar Coimbatore 1996 C.Ranganathan Vijay, Sanghavi Maaple Poove - Vikraman Vijay, Sangeetha Unakkaga - Vasantha Vaasal M.R Vijay, Swathi Maanbumigu - S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Keerthana Maanavan - Selva A. Venkatesan Vijay, Swathi Kaalamellam Vijay, Dimple, R. 1997 R. Sundarrajan Kaathiruppen Sundarrajan Vijay, Raghuvaran, - Love Today Balasekaran Suvalakshmi, Manthra Joseph Vijay, Sivaji - Once More S. A. Chandrasekhar Ganesan,Simran Bagga, Manivannan Vijay, Simran, Surya, Kausalya, - Nerrukku Ner Vasanth Raghuvaran, Vivek, Prakash Raj Kadhalukku Vijay, Shalini, Sivakumar, - Fazil Mariyadhai Manivannan, Dhamu Ninaithen Vijay, Devayani, Rambha, 1998 K.Selva Bharathy Vandhai Manivannan, Charlie - Priyamudan - Vijay, Kausalya - Nilaave Vaa A.Venkatesan Vijay, Suvalakshmi Thulladha Vijay 1999 Manamum Ezhil Simran Thullum Endrendrum - Manoj Bhatnagar Vijay, Rambha Kadhal - Nenjinile S.A.Chandrasekaran Vijay, Ishaa Koppikar Vijay, Rambha, Monicka, - Minsara Kanna K.S. Ravikumar Khushboo Vijay, Dhamu, Charlie, Kannukkul 2000 Fazil Raghuvaran, Shalini, Nilavu Srividhya Vijay, Jyothika, Nizhalgal - Khushi SJ Suryah Ravi, Vivek - Priyamaanavale K.Selvabharathy Vijay, Simran Vijay, Devayani, Surya, 2001 Friends Siddique Abhinyashree, Ramesh Khanna Vijay, Bhumika Chawla, - Badri P.A. -

Husband First Name Father

Company CIN L27102WB1999PLC089755 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITEDDate Of AGM(DD‐MON‐YYYY) 18‐DEC‐2012 Name Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 46,731.20 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for 0 FATHER/ PROPOSED FATHER/ FATHER/ MIDDLE LAST HUSBAND PIN FOLIO NO. OF INVESTMENT AMOUNT DATE OF FIRST NAME HUSBAND FIRST HUSBAND ADDRESS COUNTRY STATE DISTRICT NAME NAME MIDDLE CODE SECURITIES TYPE DUE (RS.) TRANSFER NAME LAST NAME NAME TO IEPF Amount for SANATAN KUMAR 96,BIYANIYO KI GALI, WARD NO.1, SIKAR UMA DEVI BIYANI INDIA Rajasthan 332001 1201370000023568 unclaimed and 13.20 20‐NOV‐2018 BIYANI RAJASTHAN INDIA unpaid dividend Amount for BEHARI VILL‐ PRITINAGAR, ROAD NO‐ 2, DIST‐ NADIA, KALYAN MAJUMDER INDIA West Bengal 741247 1201600000024542 unclaimed and 40.00 20‐NOV‐2018 MAJUMDER RANAGHAT WEST BENGAL INDIA unpaid dividend A‐1, VANDAN APARTMENT,, TRIBHUVAN Amount for GAJENDRA KUMAR SHANKARLAL COMPLEX, GHOD‐DOD ROAD, SURAT INDIA GGjujarat 395007 1202650000024701 unclliaime d and 20.00 20‐NOV‐2018 CHANDALIYA CHANDALIYA GUJARAT INDIA unpaid dividend A 34 SHIV SHANTI PARK, NR MIPCO CHOWKDI, Amount for BHAVESH MANU MANU MOTI GNFC ROAD, BHARUCH GUJARAT INDIA Gujarat 392015 1304140000024860 unclaimed and 0.40 20‐NOV‐2018 PATEL PATEL INDIA unpaid dividend Amount for ANIL SINGH RAMKRISHNA 16, VIVEK VIHAR COLONY, AGRA ROAD, Uttar INDIA -

Globalization and Cakewalk of Communism - from Theory to “Politricks”A Critical Analysis of Indian Scenario

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 3 Issue 5 ǁ May. 2014 ǁ PP.18-22 Globalization and Cakewalk Of Communism - From Theory to “Politricks”A Critical Analysis of Indian Scenario Devadas MB Assistant Professor Department of Media and communication Central University of Tamil Nadu ABSTRACT:There is strange urge to redefine “communism” – to bring the self christened ideology down to a new epithet-Neoliberal communism, may perfectly be flamboyant as the ideology lost its compendium and socially and economically unfeasible due to its struggle for existence in the globalised era. Dialectical materialism is meticulously metamorphosed to “Diluted materialism” and Politics has given its way for “Politricks”. The specific objective of the study is to analyze metamorphosis of communism to neoliberal communism in the antique teeming land of India due to globalization, modernity and changing technology. The study makes an attempt to analyze the nuances of difference between classical Marxist theory and contemporary left politics. The Communist party of India-Marxist (CPIM) has today become one of the multi billionaires in India with owning of one of the biggest media conglomerate. The ideological myopia shut in CPIM ostensibly digressing it from focusing on classical theory and communism has become a commodity. The methodology of qualitative analysis via case studies with respect to Indian state of West Bengal where the thirty four-year-old communist rule ended recently and Kerala where the world’s first elected communist government came to power. In both the states Communism is struggling for existence and ideology ended its life at the extreme end of reality. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78.