Article That Was Culled a Few Years Ago from Some of Salam’S Writings [1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRIESTE Feet on the Ground

The 1992 workshop on Recent Developments in the Phenomenology of Particle Physics, held in October at the International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy, and locally organized by Faheem Hussain (left) and by Nello Paver (right, of Trieste University), covered all aspects of modern quantitative research. TRIESTE Feet on the ground Established in 1964 by Abdus Salam, the International Centre for Theoreti cal Physics (ICTP), in Trieste, Italy, has naturally become one of the world's leading centres of particle physics theory. Attracting distin guished senior visitors from all over the world and with a full programme of regular symposia and workshops, it provides a valuable stepping stone to frontier research for young re searchers, particularly those from the developing countries, who would otherwise find it tough to make headway in this competitive field. Initial ICTP research interests concentrated on particle physics and plasma physics, but as interest, support and infrastructure steadily expanded, these interests widened to give a truly interdisciplinary centre with active groups in fundamental fundamental physics, be it the gen cated analyses, there is ample physics, condensed matter physics, esis of the Standard Model in the room for phenomenologists to get mathematics, plasma physics, 1960s, or supersymmetry in the 70s, aboard. superconductivity, aeronomy, micro to the more esoteric recent develop To underline and encourage this processors, climatology, and in laser, ments. In the 1980s, when shift in emphasis, in 1991 ICTP atomic and molecular physics. superstrings and other ambitious launched a workshop on phenom Originally set up under the auspices schemes for a grand picture of enology, the idea being to bring of UNESCO and the International fundamental interactions were in together the results and implications Atomic Energy Agency, ICTP has vogue, it was natural and welcome of modern precision measurements in recent years been funded mainly for ICTP to concentrate its efforts in and encourage participation in this by Italy. -

Faheem Hussain

Faheem Hussain Faheem Hussain Clinical Assistant Professor School for the Future of Innovation in Society College of Global Futures Arizona State University CAREER STATEMENT: Experienced interdisciplinary researcher of Public Policy, Information and Communication Technology (ICT), and International Development with 16 years of interdisciplinary research, academic leadership, and community engagement experience across 38 countries of five continents, with 30 universities, and 25 different regional and international organizations. Internationally known for leadership in Diversity, Sustainable Development, Refugee Research, and Women’s Empowerment. Ability to design innovative academic curricula and content, create capacity development programs, and advocate for inclusive digital justice. QUALIFICATIONS AND EMPLOYMENT EDUCATION 2008 Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering & Public Policy Carnegie Mellon University MacArthur Foundation Scholarship Thesis: Effectiveness of Technological Interventions for Education and Information Services in Rural South Asia 2006 Master of Science in Engineering & Public Policy Carnegie Mellon University 2005 Master of Science in Telecommunication Management Oklahoma State University Thesis: An Analysis of the Telecom Industry and ICT Education in Morocco, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Bangladesh 2003 Bachelor of Science in Computer Science Dhaka University, Dhaka, Bangladesh 1 of 26 ACADEMIC POSITIONS Jan. 2019 – Present Clinical Assistant Professor School for the Future of Innovation in Society Senior Sustainability -

International Theoretical Physics

INTERNATIONAL THEORETICAL PHYSICS INTERACTION OF MOVING D-BRANES ON ORBIFOLDS INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY Faheem Hussain AGENCY Roberto Iengo Carmen Nunez UNITED NATIONS and EDUCATIONAL, Claudio A. Scrucca SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CD MIRAMARE-TRIESTE 2| 2i CO i IC/97/56 ABSTRACT SISSAREF-/97/EP/80 We use the boundary state formalism to study the interaction of two moving identical United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization D-branes in the Type II superstring theory compactified on orbifolds. By computing the and velocity dependence of the amplitude in the limit of large separation we can identify the International Atomic Energy Agency nature of the different forces between the branes. In particular, in the Z orbifokl case we THE ABDUS SALAM INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS 3 find a boundary state which is coupled only to the N = 2 graviton multiplet containing just a graviton and a vector like in the extremal Reissner-Nordstrom configuration. We also discuss other cases including T4/Z2. INTERACTION OF MOVING D-BRANES ON ORBIFOLDS Faheem Hussain The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy, Roberto Iengo International School for Advanced Studies, Trieste, Italy and INFN, Sezione di Trieste, Trieste, Italy, Carmen Nunez1 Instituto de Astronomi'a y Fisica del Espacio (CONICET), Buenos Aires, Argentina and Claudio A. Scrucca International School for Advanced Studies, Trieste, Italy and INFN, Sezione di Trieste, Trieste, Italy. MIRAMARE - TRIESTE February 1998 1 Regular Associate of the ICTP. The non-relativistic dynamics of Dirichlet branes [1-3], plays an essential role in the coordinate satisfies Neumann boundary conditions, dTX°(T = 0, a) = drX°(r = I, a) = 0. -

Faheem Hussain – As I Knew Him by Pervez Hoodbhoy

Faheem Hussain – As I Knew Him by Pervez Hoodbhoy It was mid-October 1973 when, after a grueling 26-hour train ride from Karachi, I reached the physics department of Islamabad University (or Quaid-e-Azam University, as it is now known). As I dumped my luggage and “hold-all” in front of the chairman’s office, a tall, handsome man with twinkling eyes looked at me curiously. He was wearing a bright orange Che Guevara t-shirt and shocking green pants. His long beard, though shorter than mine, was just as unruly and unkempt. We struck up a conversation. At 23, I had just graduated from MIT and was to be a lecturer in the department; he had already been teaching as associate professor for five years. The conversation turned out to be the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Together with Abdul Hameed Nayyar – also bearded at the time – we became known as the Sufis of Physics. Thirty six years later, when Faheem Hussain lost his battle against prostate cancer, our sadness was beyond measure. Revolutionary, humanist, and scientist, Faheem Hussain embodied the political and social ferment of the late 1960’s. With a Ph.D that he received in 1966 from Imperial College London, he had been well-placed for a solid career anywhere in the world. In a profession where names matter, he had worked under the famous P.T. Mathews in the group headed by the even better known Abdus Salam. After his degree, Faheem spent two years at the University of Chicago. This gave him a chance to work with some of the world’s best physicists, but also brought him into contact with the American anti-Vietnam war movement and a powerful wave of revolutionary Marxist thinking. -

NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION in SOUTH ASIA Faheem Hussain

NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION IN SOUTH ASIA Faheem Hussain The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste Abstract It is exactly three years ago that first India and then Pakistan came out of the closet and tested their nuclear weapons. What is the situation now? Is India more secure now? Is Pakistan more secure now? Does the possession of nuclear weapons enhance the security of a state? These are the kinds of questions I would like to confront in this talk. THE BOMB AND INDIAN SECURITY Three years ago, on the 11th of May 1998, when India tested its nuclear weapons at Pokhran the excuse it gave was that this would enhance its security vis-a-vis China and Pakistan, which it perceived to be its enemies in the region. The argument was that the possession of nuclear weapons was necessary on the one hand to provide an answer to China's nuclear weapons and on the other hand to deter Pakistan from conventional warfare in Kashmir and elsewhere. Also India felt that it had to have nuclear weapons to be a major player on the world stage. The bomb was sold to the Indian public as providing more security. As subsequent events have shown all these hopes have proved to be myths. India's claims to nuclear power status have been dismissed by the other nuclear powers. It still lacks effective deterrent capability against China. All that has happened is that the subcontinent itself has become a more dangerous and nasty place to live in. The deterrence theory lies in shreds. -

JAMIL OMAR – INDOMITABLE FIGHTER – REST in PEACE Friday, 21 March, 2014 by Pervez Hoodbhoy

JAMIL OMAR – INDOMITABLE FIGHTER – REST IN PEACE Friday, 21 March, 2014 By Pervez Hoodbhoy It was late 1979 – or maybe early 1980 – when I first met Jamil Omar. You could right away see that he was someone unusual. With intense, sparkling eyes and a determined chin, this young man had just returned from Romania and joined Quaid-e-Azam University as a junior lecturer in the computer science department. Many of his immediate colleagues belonged to the extreme right-wing Jamaat-e-Islami. Feeling the suffocation, he soon reached out to the handful of progressive teachers and students in other departments across the university campus. He was soon to become their leader. Those were terrible times for Pakistan. After the 1977 coup of guns and theology, the jails were full, public floggings had become popular entertainment, and there was busy traffic at the gallows. On many campuses, emboldened Islami Jamiat-e-Talba students would smash their opponent’s heads with lathis, or torture others by grinding lighted cigarette butts onto their bodies. It is difficult for me to forget one such occasion when some of the QAU physics faculty – Faheem Hussain, Abdul Nayyar, and myself – received timely information and rushed to save one of our students, Tayyab Yazdani, from the Jamaat’s torture chamber in Hostel Number 2. With energy that seemed limitless, Jamil set about organizing resistance to the military dictatorship and its fascistic religious allies on campus. Secrecy was essential. Intelligence agencies were ubiquitous, snooping for every tiny hint of dissident opinion. Jamil tasked a small group of teachers – Tariq Ahsan, Mohammed Saleem, Abdul Nayyar, and myself– to secretly set up a small reading group and write something from time to time. -

Metric in Cartesian Co-Ordinates, G

ic/aa/77 With the advent of supergrsvity theories ~ the Vierbein fonttalisE INTERNAL REPORT (Limited distribution) has come into extensive use. Basically a Vierbein, .converts a flat metric in Cartesian co-ordinates, g. into a general metric, International Atomic Energy Agency according to the equation (1) ted Kations Educational. Scientific and Cultural Organization ItJTERHATICKAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS In some sense, then, the Vierbein may be regarded as a "four-dimensional square root" of the general metric tensor. In fact this applies in more or less the same sense that the Dirac spinor is regarded as "the square root of the Minkowski It-vector". The curved space-time generalization of the flat apace- time Dirac matrices, Y- > given by the commutation relations, A PRESCRIPTION! FOH n-DIMEHSIONAL VIERBEINS * [ (2) V eab transform according to the rule Ashf&que H. Bokhari (3) Mathematics Department, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan, These generalized Y-matrices are frequency used when dealing with spinor and fields in general relativity . It would be useful to be able to write Asghar Qadir ** dovm Vierbeins in an arbitrary space-time. Further, higher dimensional International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy. Vierbeins would be useful when dealing, for example, with the eleven- dimensional supergravity which reduces to SU(8) supergravity , or in tiieher dimensional theories of the Kaluza-Klein variety such as those of Chodos and ABSTRACT Detweiler or Halpern . In this paiser we provide a prescription to be able to write down a Vierbein given a metric in any number of dimensions. Recent developments in supergravity have brought the n-dimensional Before swing on we need to introduce certain notation. -

Closed String Radiation from Moving D-Branes

IC/97/158 SISSA REF 129/97/EP INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS CLOSED STRING RADIATION FROM MOVING D-BRANES Faheem Hussain Roberto Iengo Carmen Niifiez and Claudio A. Scrucca Gi O >'j MIRAMARE-TRIESTE IC/97/158 SISSA REF 129/97/EP United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization and International Atomic Energy Agency INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS CLOSED STRING RADIATION FROM MOVING D-BRANES Faheem Hussain International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy, Roberto Iengo International School for Advanced Studies and INFN, Trieste, Italy, Carmen Nunez Instituto de Astronomia y Fisica del Espacio (CONICET), Buenos Aires, Argentina and Claudio A. Scrucca International School for Advanced Studies and INFN, Trieste, Italy and Institut de Physique Theorique, Universite de Neuchatel, Switzerland. ABSTRACT We compute the amplitude for the radiation of massless NS-NS closed string states from the interaction of two moving D-branes. We consider particle-like D-branes with reference to 4-dimensional spacetime, in toroidal and orbifold compactifications, and we work out the relevant world sheet propagators within the moving boundary state formalism. We find no on-shell axion emission. For large inter-brane separation, we compute the spacetime graviton emission amplitude and estimate the average energy radiated, whereas the spacetime dilaton amplitude is found to vanish in this limit. The possibility of emission of other massless states depends on the nature of the branes and of the compactification scheme. MIRAMARE - TRIESTE October 1997 I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY The non-relativistic dynamics of Dirichlet branes [1], plays an essential role in the under- standing of string theory at scales shorter than the Planck length [2-4]. -

Summary of ICTP Activities in Support of Science in Pakistan

Summary of ICTP activities in support of science in Pakistan ICTP Public Information Office 24/07/2013 ICTP Visitors from Pakistan 1983-2012* 120 114 95 100 92 87 79 76 80 72 72 69 65 60 60 62 56 55 57 60 53 5452 Visitors 50 49 46 43 4142 42 40 40 38 Female** 40 26 20 0 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 *For the period 1970-1982, 293 visitors came from Pakistan; the total number of visitors is 2080. Average presence of women since 2001 is 20% of total visits 2001-2012. **Data on female visitors not available before 2001. } Scientific visitors from Pakistan ◦ 2080 (1970-2012) ◦ 170 women since 2001 (20%) } Pakistani participation in ICTP Programmes ◦ 18 Affiliates (From 17 Federated Institutes) ◦ 104 Associate Members (6 female) ◦ 39 Diploma Students (16 female) ◦ 31 Elettra Users Participants (4 female) ◦ 21 TRIL Fellows (3 female) ◦ 10 STEP Fellows (5 female) } Abdus Salam ◦ Member of Pakistani delegation to IAEA calls for creation of an international centre for theoretical physics at IAEA's 4th General Conference in Vienna in 1960 ◦ ICTP Founding Director 1964-1993 ◦ Nobel Laureate 1979 ◦ ICTP President 1994-1996 } ICTP Prize ◦ Abdullah Sadiq, 1987 } ICO/ICTP Prize ◦ Imrana Ashraf Zahid, 2004 ◦ Arbab Ali Khan, 2000 } ICTP Prize in Medical Physics, 2010 ◦ Shakera Khatoon Rizvi ◦ Muhammad Asif } Premio Borsellino, 2010 (from SIBPA) ◦ Fouzia Bano } Delegation from the Ministry of Science and Technology ◦ Visited ICTP in 2013 Akhlaq Ahmad Tarar, Secretary Farid Ahmad Tarar, Counsellor for Trade at the Pakistani Embassy in Rome } Delegation of COMSATS ◦ Visited ICTP in 2012 Imtinan Elahi Qureshi COMSATS Executive Director S.M. -

Cosmic Anger : Abdus Salam

COSMIC ANGER This page intentionally left blank COSMIC ANGER Abdus Salam – the fi rst Muslim Nobel scientist by Gordon Fraser 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Gordon Fraser 2008 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd., www.biddles.co.uk ISBN 978–0–19–920846–3 (Hbk.) 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Contents List of illustrations vi Introduction vii Acknowledgements and sources ix Author’s note xii 1. -

Timeline08.Pdf

located in Trieste, Italy, is a unique The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), scientific institution. Dedicated to both research and training, the Centre has earned an international reputation for its contributions to the advancement of science in the developing world. Over the past four decades approximately 100,000 scientists have visited the Centre to participate in its training and research activities. In addition, ICTP's research staff have made significant contributions to a variety of subjects in high energy physics, condensed matter physics and mathematics. More recently, the Centre has extended its research efforts to fields such as the physics of weather and climate, seismology, statistical physics and complex systems, and a variety of areas in applied physics. What follows is a historical timeline of critical events that have shaped ICTP's past accomplishments and created a strong foundation for future success. • June - University of Trieste's • February - Citizens' Committee physics faculty holds Symposium on asks Italian government to nominate Elementary Particle Interactions in Trieste as Italy’s candidate to serve the Castelletto ("small castle") in as the ‘seat’ of the proposed Miramare Park less than 10 kilometres from downtown international centre. Trieste’s mayor, Trieste. Abdus Salam invited to attend, marking first Mario Franzil, formed the committee, which consisted of • April - Sigvard Eklund, IAEA face-to-face meeting between him and Trieste's physics prominent citizens in government, commerce, education Director General, convenes community. Daniele Amati, Luciano Bertocchi, Paolo and industry, to promote city's efforts to host centre. panel of experts to devise Budinich, Nicolò Dallaporta, Giuseppe Furlan and Claudio framework for Villi—individuals who will become instrumental to the • March - Italian Government submits candidacy of institution-to-be. -

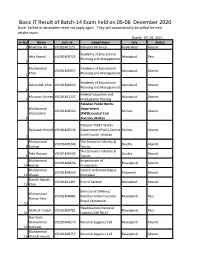

Result of Batch-14 Exam Held on 05-06 December 2020 Note: Failled Or Absentees Need Not Apply Again

Basic IT Result of Batch-14 Exam held on 05-06 December 2020 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for next retake exam. Dated: 03_02_2021 Sr.No Name test_id Department City Status 1 Mukhtiar Ali VU201401151 Pakistan Air Force Hyderabad Absent Academy of Educational Atta Rasool VU201400725 Islamabad Pass Planning and Management 2 Muhammad Academy of Educational VU201400057 Islamabad Absent Khan Planning and Management 3 Academy of Educational Kalimullah Khan VU201400016 Islamabad Absent Planning and Management 4 Federal Education and Manzoor Ahmed VU201401237 Islamabad Absent 5 Professional Training Pakistan Public Works Muhammad Department VU201400514 Multan Absent Ishaq Zahid (PWD),Central Civil 6 Division, Multan Pakistan Public Works Rasheed Ahmed VU201400536 Department (PWD),Central Multan Absent Civil Division , Multan 7 Muhammad The School of Infantry & VU201400249 Quetta Absent 8 Ittefaq Tactics The School of Infantry & Fida Hussain VU201400542 Quetta Absent 9 Tactics Muhammad Inspectorate of VU201400690 Rawalpindi Absent 10 Hassan Armaments Muhammad Central Ordnance Depot VU201400550 Khanewal Absent 11 Waqas Khanewal Danish Hassan VU201401401 Estt-VI Section Islamabad Absent 12 Khan Ministry of Defence, Muhammad VU201400882 Pakistan Armed Services Rawalpindi Pass Hassan Niaz Board Secretariat 13 Headquarters National Shakeel Yousaf VU201400781 Rawalpindi Pass 14 Logistics Cell (NLC) Hav Shah Muhammad VU201400273 National Logistics Cell Rawalpindi Absent 15 (retired) Muhammad VU201400757