Regional Services Background Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19-Resource-In

COVID-19 Resource & Information Guide for San Bernardino County Updated 6 am, July 24, 2020 This Guide to local resources is updated continuously and will be uploaded whenever sufficient changes warrant it. For live 24/7 help, call 2-1-1 or 888-435-7565 or text your zipcode to 898211 M-F, 8-5. If you have, or know of additional resources or corrections that need to be made, please let Ms. Blanks, 211 Data Curator, know at [email protected]. The guide is divided in the following sections: Federal .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 State/Region ................................................................................................................................................. 2 County ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Medical/Testing Info .................................................................................................................................... 9 Mental Health Services .............................................................................................................................. 15 Housing ....................................................................................................................................................... 16 Utilities ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Short-Term Rental Ordinance Will Go to Board of Supervisors | News | Hidesertstar.Com

9/6/2019 Short-term rental ordinance will go to Board of Supervisors | News | hidesertstar.com http://www.hidesertstar.com/news/article_45b8e608-d0f2-11e9-b520-3b04fe196abb.html TOP STORY Short-term rental ordinance will go to Board of Supervisors By Jené Estrada Hi-Desert Star 58 min ago JOSHUA TREE — About 50 Morongo Basin residents gathered in the Bob Burke Government Center to partake in a public forum Thursday morning on possible changes to short-term rental ordinances in the mountains and deserts. The San Bernardino County Planning Commission called a second hearing to vote on proposed language that would update the county development code. The ordinance would allow short-term rentals like Airbnbs in unincorporated parts of the Morongo Basin, but would also place more conditions of their operations. Staff member Suzanne Peterson presented the Land Use Department report, which she said was created with the input of code enforcement to expand the range of allowable short-term rentals and address concerns about issues like occupancy limits and parking standards. The report was originally presented in August and has since been updated to address some public comments brought up in the rst public forum. The county originally proposed to require rental owners to keep records on renters and their vehicles. The ordinance also banned additional dwelling units, or ADUs, like casitas and RVs from being used as short-term rentals. “People had comments on ADUs, advertising, pet restrictions, record keeping, density limitations and more,” Petterson said. “We also heard a lot of people say that the desert is different than the mountains.” After the August hearing, the ordinance was updated to allow for electronic record-keeping to take place on a host website, like Airbnb.com. -

Resident Survival Guide

THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION’S 2021 LOMA LINDA SURVIVAL GUIDE For Loma Linda University Medical Residents www.llusmaa.org The 2021 Survival Guide is produced by your Alumni Association, School of Medicine of Loma Linda University 11245 Anderson Street, Suite 200 Loma Linda, CA 92354 909-558-4633 www.llusmaa.org The 2021 Survival Guide Managing Editor Carolyn Wieder Assistant Editor and Advertising Nancy Yuen Design Calvin Chuang The Resident Survival Guide to Loma Linda is an official publication of the Alumni Association, School of Medicine of Loma Linda University, and is published annually for the benefit of the Loma Linda University Medical Center Residents. The Alumni Association is not responsible for the quality of products or services advertised in the Resident Guide, unless the products or services are offered directly by the Association.. Due to COVID-19 some information in this Survival Guide may be inaccurate or temporarily incorrect. Alumni Association, School of Medicine of Loma Linda University, 2021. All rights reserved. The 2021 Survival Guide is available on the Alumni Association website at www.llusmaa.org. TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME FROM THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION PRESIDENT Congratulations on matching to a residency at Loma Linda University Health. We are glad you chose this place and believe your decision to train at a Christian based residency program will be of lifelong value. You are not here by accident—I believe you are here by design. “We know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose.” Romans 8:28 (NIV). -

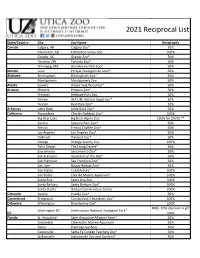

2021 Reciprocal List

2021 Reciprocal List State/Country City Zoo Name Reciprocity Canada Calgary, AB Calgary Zoo* 50% Edmonton, AB Edmonton Valley Zoo 100% Granby, QC Granby Zoo* 50% Toronto, ON Toronto Zoo* 50% Winnipeg, MB Assiniboine Park Zoo* 50% Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon* 50% Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo* 50% Montgomery Montgomery Zoo 50% Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center* 50% Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo* 50% Prescott Heritage Park Zoo 50% Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium* 50% Tuscon Reid Park Zoo* 50% Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo* 50% California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo* 100% Big Bear Lake Big Bear Alpine Zoo 100% for 2A/3C ** Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo* 50% Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo* 50% Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo* 50% Oakland Oakland Zoo* 50% Orange Orange County Zoo 100% Palm Desert The Living Desert* 50% Sacramento Sacramento Zoo* 50% San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay* 50% San Francisco San Francisco Zoo* 50% San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo* 50% San Mateo CuriOdyssey* 100% San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium* 100% Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo 100% Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo* 100% Santa Clarita Gibbon Conservation Center 100% Colorado Pueblo Pueblo Zoo* 50% Connecticut Bridgeport Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo* 100% Delaware Wilmington Brandywine Zoo* 100% FREE- 10% discount in gift Washington DC Smithsonian National Zoological Park* DC shop Florida St. Augustine Saint Augustine Alligator Farm* 50% Clearwater Clearwater Marine Aquarium 50% Davie Flamingo Gardens 50% Gainesville Santa Fe College Teaching Zoo* 50% Jacksonville Jacksonville -

A Regular Meeting of the Board of Commissioners of the Housing Authority of the County of San Bernardino

A REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE HOUSING AUTHORITY OF THE COUNTY OF SAN BERNARDINO TO BE HELD AT 715 EAST BRIER DRIVE SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 FEBRUARY 11, 2020 AT 3:00 P.M. AGENDA PUBLIC SESSION 1) Call to Order and Roll Call 2) Additions or deletions to the agenda 3) General Public Comment - Any member of the public may address the Board of Commissioners on any matter not on the agenda that is within the subject matter jurisdiction of the Board. 4) Receive Board Building Presentation for February 11, 2020 – (MTW Overview). (Page 1) DISCUSSION CALENDAR (Public comment is available for each item on the discussion calendar) 5) Receive the Executive Director’s Report dated February 11, 2020. (Page 2) 6) Adopt Resolution No. 77 approving revision to the Administrative Plan governing the Housing Authority of the County of San Bernardino’s rental assistance program. (Pages 3-16) 7) Approve of an amended Conflict of Interest Code pursuant to the Political Reform Act of 1974. (Pages 17-22) 8) Approve, confirm and ratify all action from May 6, 2014 to July 9, 2019 heretofore taken by the Board of Governors of the Housing Authority of the County of San Bernardino, and the officers, employees and agents of the Housing Authority of the County of San Bernardino are authorized and directed, for and in the name and on behalf of the Housing Authority of the County of San Bernardino, to do any and all things and take any and all actions and execute and deliver any and all certificates, agreements, assignments, and other documents, which they, or any of them, may deem necessary or advisable in order to consummate and to effectuate the actions, including but not limited to the following: a. -

COVID-19 Resource & Information Guide for San Bernardino County

COVID-19 Resource & Information Guide for San Bernardino County Updated 9 am, July 31, 2020 This Guide to local resources is updated continuously and will be uploaded whenever sufficient changes warrant it. For live 24/7 help, call 2-1-1 or 888-435-7565 or text your zipcode to 898211 M-F, 8-5. If you have, or know of additional resources or corrections that need to be made, please let Ms. Blanks, 211 Data Curator, know at [email protected]. The guide is divided in the following sections: Federal .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 State/Region ................................................................................................................................................. 2 County ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Medical/Testing Info .................................................................................................................................... 9 Mental Health Services .............................................................................................................................. 10 Housing ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 Utilities ....................................................................................................................................................... -

090215 Regular Meeting

PLANNING COMMISSION MEETING AGENDA September00 2, 2015 PLANNING COMMISSION Chairman Craig Smith Vice-Chairman Anne Bush Commissioner Paul Senft Commissioner Ron Tholen Commissioner Tim Breunig CITY STAFF Community Development Director James J. Miller City Planner Janice Etter Principal Planner Ruth Lorentz Associate Planner Andrew Mellon Assistant Planner Nathan Castillo City Attorney Andy Maiorano 39707 Big Bear Boulevard, Big Bear Lake, California 92315 INFORMATION FOR THE PUBLIC The Planning Commission meets regularly on the first and third Wednesdays of the month at 1:15 p.m. in Hofert Hall at the Civic Center located at 39707 Big Bear Boulevard. Procedure to Address the Planning Commission The Planning Commission encourages free expression of all points of view. To allow all persons to speak, given the length of the agenda, please keep your remarks brief. If others have already expressed your position, you may simply indicate that you agree with a previous speaker. If appropriate, a spokesperson may present the views of your entire group. To encourage all views and promote courtesy to others, the audience should refrain from clapping, booing or shouts of approval or disagreement. Public Forum The public may address the Planning Commission by completing a speaker card and submitting it to the Commission Secretary. The speaker cards are located on the table at the back of the Commission Chambers. During the “Public Forum” your name will be called. Please step to the microphone and give your name and city of residence for the record before proceeding. All remarks shall be addressed to the Commission as a body only. No person other than a member of the Commission and the person having the floor shall enter into any discussion without the permission of the Commission Chairman. -

Reciprocal and Free Zoos

NMBPS RECIPROCAL LIST for 201 4 --All facilities offer 50% off regular admission and must show valid ID to enter facilities Please remember to bring your NMBPS HAWAII MISSOURI Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium membership card with you when you visit Waikiki Aquarium Dickerson Park Zoo Zoo America in order to receive your member benefits. IDAHO Endangered Wolf Center RHODE ISLAND *free admission Pocatello Zoo Kansas City Zoo Roger Williams Park & Zoo **free and/or discounts for stores, Tautphaus Park Zoo St. Louis Zoo ** SOUTH CAROLINA andattractions, benefits and/or parkingfor the reciprocal program. Zoo Boise MONTANA Greenville Zoo ALABAMA ILLINOIS Zoo Montana Riverbanks Zoo & Garden Birmingham Zoo Cosley Zoo * NEBRASKA SOUTH DAKOTA Montgomery Zoo Henson Robinson Zoo Lincoln Children’s Zoo Bramble Park Zoo ALASKA Lincoln Park Zoo ** Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo Great Plains Zoo & Delbridge Museum Alaska SeaLife Center Miller Park Zoo Riverside Discovery Center TENNESSEE ARIZONA Niabi Zoo NEW HAMPSHIRE Chattanooga Zoo PLEASE NOTE: Heritage Park Zoological Sanctuary Peoria Zoo Squam Lakes Natural Science Center Knoxville Zoo Participation in the Reid Park Zoo Scovill Zoo NEW JERSEY Memphis Zoo reciprocal program with The Navajo Nation Zoo & INDIANA Bergen County Zoological Park Nashville Zoo @ Grassmere the NMBPS is voluntary. Botanic Garden * Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo Cape May County Park & Zoo* TEXAS Occasionally, zoos and The Phoenix Zoo Mesker Park Zoo & Botanic Garden ** Turtle Back Zoo Abilene Zoo ARKANSAS Potawatomi Zoo NEW MEXICO Caldwell Zoo aquariums decide they Little Rock Zoo Washington Park Zoo Alameda Park Zoo Cameron Park Zoo wish to change their CALIFORNIA IOWA Living Desert Zoo & Garden State Park Dallas Zoo participation. -

2021 Reciprocal Zoos and Aquariums

2021 Reciprocal Zoos and Aquariums The following is a list of zoo and aquariums in which admission is usually free upon presentation of your FOTAZ membership card and valid identification. Some of the zoos may require a reduced admission price. If zoo admission is FREE, other compensations will be offered to members. (Percentage off gift shop purchases, marked below with **.) However, occasionally a previously reciprocal zoo might withdraw from this program. Please check with zoo you intend to visit or call (318) 441-6810 and we’ll be glad to check the most current list or send you a copy. Please note that this list is subject to change without notice. CANADA GEORGIA Calgary Zoo (Calgary – Alberta) 50% Chehaw Wild Animal Park (Albany) Granby Zoo (Quebec – Granby) 50% Zoo Atlanta (Atlanta) 50% Toronto Zoo (Toronto) 50% Assiniboine Park Zoo (Winnipeg-Manitoba) 50% HAWAII Waikiki Aquarium (Honolulu) 50% MEXICO Parque Zoologico de Leon (Leon) 50% IDAHO Idaho Falls Zoo at Tautphaus Park (Idaho Falls) ALABAMA Zoo Boise (Boise) Birmingham Zoo (Birmingham) 50% Zoo Idaho (Pocatello) Montgomery Zoo (Montgomery) 50% ILLINOIS ALASKA Cosley Zoo (Wheaton) Alaska SeaLife Center (Seward) 50% Henson Robinson Zoo (Springfield) Lincoln Park Zoo (Chicago) ** ARIZONA Miller Park Zoo (Bloomington) Heritage Park Zoo (Prescott) 50% Niabi Zoo (Coal Valley) Reid Park Zoo (Tucson) 50% Peoria Zoo (Peoria) The Phoenix Zoo (Phoenix) 50% Scovill Zoo (Decatur) 50% SEALIFE Arizona Aquarium (Tempe) 50% INDIANA ARKANSAS Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo (Fort Wayne) 50% Little -

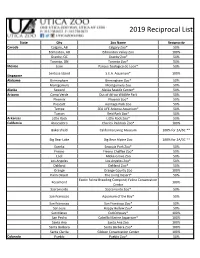

2019 Utica Zoo Reciprocal List

2019 Reciprocal List State City Zoo Name Reciprocity Canada Calgary, AB Calgary Zoo* 50% Edmonton, AB Edmonton Valley Zoo 100% Granby, QC Granby Zoo* 50% Toronto, ON Toronto Zoo* 50% Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon* 50% Sentosa Island S.E.A. Aquarium* 100% Singapore Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo* 50% Montgomery Montgomery Zoo 50% Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center* 50% Arizona Camp Verde Out of Africa Wildlife Park 50% Phoenix Phoenix Zoo* 50% Prescott Heritage Park Zoo 50% Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium* 50% Tuscon Reid Park Zoo* 50% Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo* 50% California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo* 100% Bakersfield California Living Museum 100% for 2A/6C ** Big Bear Lake Big Bear Alpine Zoo 100% for 2A/3C ** Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo* 50% Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo* 50% Lodi Micke Grove Zoo 50% Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo* 50% Oakland Oakland Zoo* 50% Orange Orange County Zoo 100% Palm Desert The Living Desert* 50% Exotic Feline Breeding Compund; Feline Conservation Rosamond 100% Center Sacramento Sacramento Zoo* 50% San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay* 50% San Francisco San Francisco Zoo* 50% San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo* 50% San Mateo CuriOdyssey* 100% San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium* 100% Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo 100% Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo* 100% Santa Clarita Gibbon Conservation Center 100% Colorado Pueblo Pueblo Zoo* 50% Connecticut Bridgeport Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo* 100% Delaware Wilmington Brandywine Zoo* 100% FREE- 10% discount in Washington DC Smithsonian National Zoological Park* gift shop -

COVID-19 Resource & Information Guide for San Bernardino County

COVID-19 Resource & Information Guide for San Bernardino County Updated 7 am, May 29, 2020 This Guide to local resources is updated continuously and will be uploaded whenever sufficient changes warrant it. For live 24/7 help, call 2-1-1 or 888-435-7565. If you have, or know of additional resources or corrections that need to be made, please let Ms. Blanks, 211 Data Curator, know at [email protected]. The guide is divided in the following sections: Federal .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 State/Region ................................................................................................................................................. 2 County ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Medical/Testing Info .................................................................................................................................... 6 Mental Health Services .............................................................................................................................. 10 Housing ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 Utilities ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Reciprocal Zoos & Aquariums

Cosley Zoo | Reciprocal Zoos & Aquariums As a member of Cosley Zoo, you receive free or discounted admission to the following facilities. You may be asked to present your Cosley Zoo membership card and a photo ID. The number of visitors admitted with a family membership may vary and parking may or may not be included. This list is subject to change and restrictions may apply; please contact the facility prior to your visit to verify their status. An updated list is always available on our membership page at cosleyzoo.org. Canada Colorado Indiana Calgary Calgary Zoo, 50% off admission Pueblo Pueblo Zoo, 50% off admission Evansville Mesker Park Zoo & Botanic Granby Granby Zoo, 50% off admission Garden, Free admission Toronto Toronto Zoo, 50% off admission Connecticut Fort Wayne Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo, 50% Winnipeg Assiniboine Park Zoo, 50% off Bridgeport Connecticut’s Beardsley Zoo, off admission admission Free admission Lafayette Columbian Park Zoo*, Free Norwalk The Maritime Aquarium at admission, 10% discount in gift Mexico Norwalk, Free admission shop Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon, 50% Michigan City Washington Park Zoo, 50% off off admission Delaware admission Wilmington Brandywine Zoo, Free admission South Bend Potawatomi Zoo, 50% off Alabama admission Birmingham Birmingham Zoo, 50% off District of Columbia admission Washington Smithsonian National Zoological Iowa Montgomery Montgomery Zoo and Mann Park*, Free admission, 10% Des Moines Blank Park Zoo, Free admission Wildlife Learning Museum, 50% discount in the gift shops Dubuque